Abstract

Purpose

This study was to identify factors that affect breast cancer patients' intentions to participate in cancer rehabilitation therapy. Such findings could be utilized early in the rehabilitation process to improve treatment outcomes and quality of life.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 300 breast cancer patients (≥20 years old) receiving post-surgery outpatient care was used. A self-administrated survey was conducted from June 15 to July 25, 2012. The questionnaire included basic subject data, physical symptoms, optimism, and social support.

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer affecting women in South Korea. Its incidence is increasing at a rate of 5.9% per year. In 1999, the incidence was 12.5 cases per 100,000 individuals, and by 2011 it had increased to 25.2 cases per 100,000 individuals.1) Recent developments in medical technology and active treatment have improved the 5-year survival rate for breast cancer patients to as high as 91.3%. In 2011, the number of 5-year breast cancer survivors was 12,518.1) However, the increases in incidence and survival rates have led breast cancer patients to experience considerable lifelong physical, psychological, and social distress.2) While pain significantly decreases with time post-surgery, 26% of patients continued to report pain as much as 5 years post-surgery, which negatively affected their quality of life.3) Rehabilitation therapy may help reduce physical symptoms (e.g., fatigue) and improve the quality of life.4) Therefore, rehabilitation has been emphasized throughout the cancer treatment process to preserve patients' functional status and improve their quality of life.4)

During treatment, breast cancer patients experience objective physical symptoms such as lymphedema, limited shoulder joint movement, and weakened hand and arm muscles. They also experience subjective physical symptoms such as fatigue, sleep disorders, pain, numbness, and changes in sensation.3) As a result of these physical symptoms, breast cancer patients often experience emotional distress such as mental illness, depression, a sense of loss due to the physical changes associated with the disease or treatment, feelings of abandonment by medical staff, and fears of cancer recurrence.5)

Patients' tendencies towards optimism and their particular coping styles are important in overcoming physical and emotional symptoms. Indeed, optimistic cancer patients tend to use coping strategies that are effective in resolving problematic situations that affect their physical functioning, disease outcomes, psychological adaptations, and ultimately, their survival rates.6) Social support is an important environmental factor during treatment because it provides cancer patients with a source of strength for facing various crises.7) In fact, social support is consistently associated with positive outcomes in cancer patients, including better adjustment to living with cancer, improved coping, and enhanced quality of life.78)

Rehabilitation therapy seeks to improve patients' quality of life rather than prolonged survival. Physical therapy and exercise can result in improvements in arm and shoulder functions. Physiotherapeutic interventions also help to reduce lymph volume and maintain the health of the skin and supporting structures. Furthermore, pain management after breast cancer surgery can reduce the risk of injuries to muscles and ligaments that usually heal and are more likely to be transient or neuropathic pains due to nerve tissue damage.9) Previous studies obtained patients' consent to participate in cancer rehabilitation therapy by inquiring about their willingness to participate in physical therapy, edema management, and pain management; thus, we focused on these measures in the present study. Studies on rehabilitation therapy in non-Korean cancer patients have mainly examined or developed various interventions to improve quality of life,10) reduce symptoms,11) or investigate coping strategies.12) Researchers have also recently examined a program aimed at improving the rehabilitation of breast cancer survivors.13) Most studies on rehabilitation therapy for Korean cancer patients have focused on the effectiveness of treatment or exercise programs, rather than examining factors that may influence the patients' intentions to participate in cancer rehabilitation therapy.

In recent years, self-determination has become increasingly important. Breast cancer patients themselves must be determined to undergo rehabilitation, which itself would counteract and help in overcoming their physical and mental problems, ultimately improving their quality of life. Thus, in addition to physical symptoms and emotional problems, the patients' optimism, coping styles, and social support should be considered as important determinants of their intentions to undergo rehabilitation therapy.

The purpose of this study was to identify factors that influence breast cancer patients' intentions to participate in rehabilitation therapy. The goal was to provide data to assist in the development of measures to promote cancer rehabilitation therapy and, ultimately, contribute to a better quality of life for breast cancer patients. To identify the differences in intentions to undergo cancer rehabilitation therapy, this study had three specific aims: 1) identification by demographic and disease-related characteristics, 2) identification by physical symptoms, optimism, coping styles, and social support availability, and 3) identification of other factors that influence breast cancer patients' rehabilitation intentions.

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study examining factors that influence the intentions of breast cancer patients to participate in cancer rehabilitation therapy. Three hundred breast cancer patients who underwent surgery following their diagnoses were enrolled. The selection criteria were as follows: 1) adults aged 20 and above, 2) women receiving hospital treatment or outpatient treatment in a general hospital located in S city in South Korea following a breast cancer surgery, and 3) women with no other cancer diagnoses.

Questionnaires were distributed at the hospital to participants who were being cared for as either outpatients or inpatients. The self-report questionnaire took approximately 10~12 minutes to complete. Data was collected between May 9, 2012 and June 30, 2012. A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed, and 330 patients responded (response rate=82.5%). From the 330 respondents, 30 participants were excluded due to missing information regarding demographic characteristics.

This study was conducted according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB file No: 2012-0228) of the general specialized care institution from which we recruited the participants. This study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Every effort was made to ensure participant confidentiality and anonymity.

Two oncology nurses with more than 10 years of clinical experience, and two professors of nursing science tested the content validity of the scales measuring physical symptoms, optimism, coping style, and social support.

Optimism was measured using the Life Orientation Test (LOT-R),16) which was translated into Korean by Kim and So.2) The LOT-R consists of 10 questions, each rated on a 5-point scale. Higher scores indicate a greater tendency towards optimism. Cronbach's α for the LOT-R was 0.62 in the present study, which is well within the acceptable range of 0.56 to 0.86 found in the original study.16)

Coping style was assessed using the Cancer Coping Questionnaire, which was developed by Moorey, Frampton, and Greer,17) and then revised and modified by Kim et al6) for use in a Korean population. The Korean Cancer Coping Questionnaire (K-CCQ) includes 23 items rated on a 4-point scale, with higher scores indicating more frequent use of a positive coping style. The scale yields four subscales: interpersonal coping (α= 0.92), positive reorganization (α= 0.88), active coping (α= 0.71) and planning (α= 0.80). The Cronbach's α in the Kim et al6) study was 0.90, and was 0.93 in our present study.

Social support was measured with Tae's scale,18) which includes eight items for family support and eight items for medical support, all rated on a 5-point scale. Lower scores indicate higher social support. Tae18) reported Cronbach's α of 0.82 and 0.84 for family and medical support, respectively. In our study, Cronbach's α was 0.94 for the whole scale, 0.90 for family support, and 0.89 for medical support.

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics, including the means and standard deviations for each variable, were calculated. We conducted t-tests and cross-tabulation analyses to test for significant differences in participant intentions regarding cancer rehabilitation therapy according to general and disease-related characteristics. Finally, a binomial logistic regression analysis was employed to explore variables affecting the intention to participate in cancer rehabilitation therapy. The goodness of fit for the final binomial logistic regression model containing independent variables was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

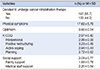

Table 1 shows the number of participants who intended to undergo rehabilitation therapy, as well as the means and proportions of the major variables. The majority of participants (55.7%) responded "yes" regarding their intention to participate in cancer rehabilitation therapy. The mean (SD) score for physical symptoms was 17.82 (5.78) out of a possible 40, and the mean level of optimism was 3.60 (0.54) out of 5. The mean coping style score was 2.97 (0.42) out of 4, while social support had a mean of 2.03 (0.79) out of 5.

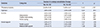

Information regarding the demographic and disease-related characteristics of the participants, and the differences in their intentions to undergo cancer rehabilitation therapy according to these characteristics, are shown in Table 2. Considering the demographic characteristics, statistically significant differences were found between participants who were willing to undergo rehabilitation and those who were not, with regard to age, education level, and financial backing. Specifically, participants who were willing to participate in cancer rehabilitation therapy were significantly younger, had higher levels of education, and were more likely to have health insurance coverage.

Among disease-related characteristics, differences in intentions were found with respect to the duration after surgery, type of surgery, whether participants were currently undergoing chemotherapy, and the stage of cancer. Considering the duration post-surgery, participants were more likely to say "yes" for cancer rehabilitation therapy when the post-surgery period was <12 months compared to when it was >12 months. The percentage of patients willing to participate based on the type of surgery was: breast-conserving operation (BCO) without axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) 47.9%; modified radical mastectomy (MRM) and ALND 26.3%; MRM without ALND 13.2%; and BCO with ALND 12.6%. These values differed significantly. In terms of treatment, participants currently receiving chemotherapy were more likely to participate in rehabilitation therapy than were those not receiving chemotherapy. Regarding the disease phase, of those who intended to participate in rehabilitation, 46.1% of participants had Stage II cancer, 32.3% had Stage I, 19.2% had Stage III, and 2.4% had Stage IV. All of these groups differed significantly from each other.

Differences in patient intentions to participate in cancer rehabilitation therapy based on physical symptoms, optimism, coping style, and social support are shown in Table 3. Participants reporting more physical symptoms were significantly more likely to participate in rehabilitation than those with lower scores. Regarding coping styles, participants with higher total K-CCQ scores were significantly more likely to participate in rehabilitation than those with lower scores. Optimism and social support levels did not show differences in intentions to undergo rehabilitation therapy.

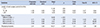

Factors affecting patient intentions regarding cancer rehabilitation therapy are shown in Table 4. To build the final model, a binomial logistic regression analysis was conducted with independent variables chosen based on the results of the t-tests and cross-tabulation analysis (p<0.05). Specifically, statistically significant variables were selected (i.e., age, educational level, treatment fee support, length of post-surgery period, type of surgery, chemotherapy, cancer stage, physical symptoms, and cancer coping style).

In the final model, length of post-surgery period, type of surgery, and physical symptoms significantly affected the decision to undergo cancer rehabilitation therapy. Length of post-surgery period and type of surgery (categorical variables) were converted into dummy variables for the logistic regression analysis with the enter method. When calculating for duration of the post-surgery period and keeping "<12 months" as the reference, odds ratios (ORs) were 0.217 for "12~48 months" and 0.22 for ">48 months". Calculation for type of surgery, keeping "MRM and without ALND" as the reference, the ORs were 2.039 for "BCO and without ALND," 2.039 for "BCO and ALND," and 12.16 for "MRM and ALND." The OR was 1.509 for physical symptoms.

An assessment of the level of fitness of the final model showed that the -2 log-likelihood value was 206.182, while the chi-square goodness of fit value was 205.844 (df=22, p<.001), indicating that our final regression model was a good fit for the data. In addition, the Hosmer-Lemeshow value was 4.284 (df=8, p=0.831), indicating that the model was a good fit. Furthermore, the classification accuracy of this model was 86%, with an explanatory power of 66.5% for predicting participants' intention to undergo cancer rehabilitation therapy, assessed using Nagelkerke's measure (R2=0.665).

Cancer survival rates continue to increase, emphasizing the importance of rehabilitation to preserve the functional status of patients and to improve their quality of life. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to identify the factors that influence the intention of breast cancer patients to undergo rehabilitation therapy.

Participant intentions regarding rehabilitation differed significantly by age, education level, and treatment fee burden. Younger college graduates and those whose treatment fees were paid by health insurance were more willing to participate in rehabilitation. These findings are similar to results reported by Park and Hwang4) who observed that younger cancer patients with higher education and better financial means were more likely to actively seek therapy than were patients who did not have these attributes. It is of concern that as age decreased, the rate of decision involvement increased, although this interpretation requires some caution because of the low ratio of breast cancer patients in their 20s and 30s among the study subjects. Since the proportion of breast cancer patients who are ≥50s is increasing,1) it is of great concern that results show that the lowest rate of decision involves female patients in their 50s. It is necessary to investigate the factors that both promote as well as obstruct the intentions of 50 years and older breast cancer patients to undergo rehabilitation.

Socioeconomic status, including education and economic levels, has also been found to significantly affect cancer survivors' rehabilitation.19) Thus, people who paid for medical expenses in the group that intended to have rehabilitation treatment were mainly spouses and health insurance companies. Spouses paying for medical expenses are considered to be providing family support. Although family support, which is a subordinate factor of social support, did not affect the participant intentions of rehabilitation treatment in this study, financial support in the decision-making process is still considered important. Thus, careful attention should be paid to socioeconomically disadvantaged groups in the clinical setting when developing targeted rehabilitation programs.

Intentions regarding rehabilitation therapy also differed significantly by the length of the post-surgery period, type of surgery, whether they were currently receiving chemotherapy, and the stage of cancer. Specifically, a shorter post-surgery period was a significant factor in the decision to participate in rehabilitation. This is probably because there are often more complications 6 months post-surgery,20) and discomfort levels within the first 6 months can predict the level of chronic discomfort patients will experience in future.21) Therefore, breast cancer patients would benefit greatly from early rehabilitation programs. Surgery type also significantly affected which patients intended to undergo rehabilitation. Specifically, participants who underwent MRM and ALND were more likely to undergo therapy than were those in the other surgery groups. This may be because patients who have undergone MRM and ALND tend to exhibit a higher frequency of physical (e.g., fatigue, pain, and lymphedema) and psychosocial problems, in addition to more limitations in their daily living activities.22) Thus, participants who received ALND required rehabilitative management to decrease any possible post-surgery physical and psychological problems, and it was essentially reconfirmed that physical and psychological problems are significant factors in intention of rehabilitation treatment. Therefore, nurses should pay attention to disease characteristics, such as the type of surgery or the length of the post-surgery period, to predict those patients who require rehabilitation. Furthermore, we found that participants who were currently receiving chemotherapy and those with a more advanced cancer stage were more likely to pursue rehabilitation therapy. Similarly, Lee et al23) found that cancer patients in advanced stages who experience chemotherapy complications had greater physical and psychological burden. This was believed to be due to the problems that such patients have in physical functioning and in performing daily life routine, which often require them to request additional resources or support.

People who were willing to participate in cancer rehabilitation therapy reported more physical symptoms and had a more positive coping style than did those who were not. Further, the degree of physical symptoms affected the patients' intentions to undergo cancer rehabilitation therapy, probably because greater physical symptoms and more pain are associated with decreased quality of life24) and greater difficulty with psychosocial adaptation.25) Cheville et al26) conducted a survey of outpatient cancer patients and reported that 71.8% of cases experienced at least one physical symptom related to their cancer. To improve the quality of life of breast cancer patients, it is necessary to predict which patient will require rehabilitation, and administer therapy to those patients in a timely fashion. Therefore, nurses must actively listen to the physical symptoms reported by cancer patients in order to provide appropriate emotional support and to sensitively assess changes in the patients' conditions.

For cancer coping styles, the highest subscale scores were for positive restructuring, followed by interpersonal coping, active coping, and planning. Thus, patients with breast cancer tended to use a problem-focused coping style (e.g., seeking information, cognitive reconstruction), rather than an emotion-focused style, when dealing with problematic situations.2) This may be related to a tendency for patients to perceive breast cancer as controllable as they gather information on the disease and its treatment, allowing them to realistically evaluate and actively try to change their circumstances.27) In addition, Park and Hwang4) found that breast cancer patients were better able to cope if they used positive strategies that actively dealt with the reality of the situation, made plans for the future, reorganized their lives into a more optimistic direction, and accepted help from those closest to them. Thus, it seems that breast cancer patients experience enormous stress in the process of their diagnosis, treatment, recovery, and rehabilitation. The effects of coping strategies and resources for relieving stress are likely to differ from person to person. Therefore, cancer rehabilitation therapy programs should include effective coping strategies tailored to the suit the main sources of stress experienced by patients in each disease phase.

We found no significant differences in optimism and social support levels between participants who intended to undergo cancer rehabilitation therapy and those who did not. Results for optimism were similar to those reported in previous studies conducted in Korea4) and China.28) In this study, it was assumed that optimistic patients would take positive measures against cancer, which would affect rehabilitation treatment participation. Optimism and coping styles are related; nevertheless, further research is required to investigate whether these factors actually influence patients' own decision-making processes regarding treatment options.24) Additionally, optimism levels according to disease severity and cancer stage may vary greatly from person to person. Future research should examine whether changes in optimism according to disease phase affects the breast cancer patients' intentions for continuing treatment. The participants reported a mean (SD) score on the social support scale of 2.03 (0.79) points (out of 5), which was lower compared with the mean scores for the family support (M=4.35, SD= 0.68, out of 5) and medical staff support (M=4.39, SD= 0.62, out of 5) subscales in patients with early stage breast cancer.2) Such differences in the results could be caused by a number of factors. Participants of Kim and So's study2) had Stages I and II breast cancer, and had undergone operations or received anti-cancer chemotherapies and radiotherapies after diagnosis. Although the numbers were smaller than that of patients who had not relapsed, our present study included Stages III and IV breast cancer patients as well as patients with relapses, and also patients who were still undergoing anti-cancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Therefore, it is believed that the participants could have thought the support they were getting from their families or medical teams was insufficient. Further research is needed to verify the amount of support expected from families and medical teams, depending on the severity of disease and the type of treatment required.

No significant differences were found between social support and decision to seek rehabilitation therapy. In this study, social support was measured by two factors: family support and medical support. However, the bigger the social network, the more social resources breast cancer patients acquire and the more support systems they can have access to.29) Therefore, it is suggested that additional research with regard to cancer rehabilitation treatment be conducted to assess support systems, examining not only the support from family members and medical teams but also include social support from diverse networks such as friends, self-dependent groups, and society.

To summarize, the greatest influences on participants' intention of cancer rehabilitation treatment are the types of operation, the length of time after the operation, and the related physical symptoms. Therefore, we suggest that rehabilitation programs should be developed to predict and manage physical and psychosocial problems. These programs could be implemented before surgery and be tailored to the type of surgery. By exploring various intervention methods to appropriately control and manage the factors identified herein, we can help patients make better decisions whether to participate in rehabilitation, in addition to developing more efficient clinical programs for improving their quality of life.

While this study has considerable strength, it is also important to note the limitations. First, we used a cross-sectional design and thus, cannot identify causative factors of patients' intentions regarding rehabilitation therapy. Moreover, care must be taken when generalizing the results of this study, as the sample was not randomly selected, but drawn from patients receiving inpatient or outpatient breast cancer treatment at a single general hospital located in S city in South Korea. This study especially had a high rate of patients in their 40s and 50s, with Stage I and Stage II cancer, which are comparatively low cancer stages. Finally, the results cannot be generalized to breast cancer patients or survivors.

As survival rates continue to increase, rehabilitation therapy is becoming increasingly important for helping breast cancer patients to adapt to their altered lives after surgery and improve their quality of life. The results of this study indicate that the length of the post-surgery period, type of surgery, and level of physical symptoms were most likely to affect breast cancer patients' intentions to participate in rehabilitation therapy. To help patients decide whether they wish to receive cancer rehabilitation therapy, nurses must consider the type of surgery and the presence/severity of physical symptoms as soon as possible after surgery. Furthermore, nurses should develop the abilities to predict in advance the type of operation and complications expected, in order to provide accurate information to allow patients to independently decide whether to participate in rehabilitation treatment, and to share the financial burdens of expenses with social organizations, which would help in providing psychological support. In this regard, our investigation could contribute to the development of rehabilitation programs that take into account the predictors observed in this study. These efforts will better identify the relationship between the multidimensional factors explored herein and the participants' intentions to seek cancer rehabilitation post-treatment.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Participants' Intentions to Undergo Cancer Rehabi-li-tation Therapy and Their Physical Symptoms, Optimism, Coping Styles, and Social Support (N=300)

Table 2

Intentions to Undergo Rehabilitation Therapy by Demographic and Disease-related Characteristics (N=300)

Table 3

Differences in the Decision to Undergo Cancer Rehabilitation Therapy by Physical Symptoms, Optimism, Coping Style, and Social Support (N=300)

Table 4

Factors Affecting the Decision to Undergo Cancer Rehabilitation Therapy (N=300)

References

1. Korea National Cancer Information Center. Cancer facts & figures 2013. Accessed February 2, 2015. http://www.cancer.go.kr.

2. Kim HY, So HS. A structural model for psychosocial adjustment in patients with early breast cancer. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012; 42(1):105–115.

3. Chun MS, Moon SM, Lee HJ, Lee EH, Song YS, Chung YS, et al. Arm morbidity after breast cancer treatments and analysis related factors. J Korean Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2005; 23:32–42.

4. Park BW, Hwang SY. Depression and coping in breast cancer patients. J Breast Cancer. 2009; 12(3):199–209.

5. Lu W, Cui Y, Chen X, Zheng Y, Gu K, Cai H, et al. Changes in quality of life among breast cancer patients three years post-diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009; 114(2):357–369.

6. Kim JN, Kwon JH, Kim SY, Yu BH, Hur JW, Kim BS. Validation of Korean-cancer coping questionnaire (K-CCQ). Korean J Health Psychol. 2004; 9(2):395–414.

7. Knobf M. Clinical update: psychosocial responses in breast cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011; 27(3):e1–e14.

8. Kasparian NA, McLoone JK, Butow PN. Psychological responses and coping strategies among patients with malignant melanoma: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2009; 145(12):1415–1427.

9. Winters-Stone KM, Schwartz AL, Hayes SC, Fabian CJ, Campbell KL. A prospective model of care for breast cancer rehabilitation: bone health and arthralgias. Cancer. 2012; 118(8 Suppl):2288–2299.

10. Ferrer RA, Huedo-Medina TB, Johnson BT, Ryan S, Pescatello LS. Exercise interventions for cancer survivors: a meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2011; 41(1):32–47.

11. Bender CM, Engberg SJ, Donovan HS, Cohen SM, Houze MP, Rosenzweig MQ, et al. Symptom clusters in adults with chronic health problems and cancer as a comorbidity. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008; 35(1):E1–E11.

12. Hughes A, Gudmundsdottir M, Davies B. Everyday struggling to survive: experience of the urban poor living with advanced cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007; 34(6):1113–1118.

13. McNeely ML, Binkley JM, Pusic AL, Campbell KL, Gabram S, Soballe PW. A prospective model of care for breast cancer rehabilitation: postoperative and post reconstructive issues. Cancer. 2012; 118(8 Suppl):2226–2236.

14. Yoo YS. Effects of aquatic exercise program on the shoulder joint function, immune response and emotional state in postmastectomy patients. J Cathol Med Coll. 1996; 49(2):806–823.

15. Lee MH. An effect of rhythmic movement therapy for adaptation state in mastectomy patients. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. 1995; 2(1):67–85.

16. Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994; 67(6):1063.

17. Moorey S, Frampton M, Greer S. The Cancer Coping Questionnaire: a self-rating scale for measuring the impact of adjuvant psychological therapy on coping behaviour. PsychoOncology. 2003; 12(4):331–344.

18. Tae YS. Study on the correlation between perceived social support and depression of the cancer patients [dissertation]. Seoul: Ewha Womans Univ.;1985.

19. Holm LV, Hansen DG, Larsen PV, Johansen C, Vedsted P, Bergholdt SH, et al. Social inequality in cancer rehabilitation: a population-based cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2013; 52(2):410–422.

20. Eom A. Effect of a TaiChi program for early mastectomy patients. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2007; 13:43–50.

21. Albert US, Koller M, Kopp I, Lorenz W, Schulz KD, Wagner U. Early self-reported impairments in arm functioning of primary breast cancer patients predict late side effects of axillary lymph node dissection: results from a population-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006; 100:285–292.

22. Devoogdt N, Van Kampen M, Christiaens MR, Troosters T, Piot W, Beets N, et al. Short-and long-term recovery of upper limb function after axillary lymph node dissection. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2011; 20(1):77–86.

23. Lee JA, Lee SH, Park JH, Park JH, Kim SG, Seo JH. Analysis of the factors related to the needs of patients with cancer. J Prev Med Public Health. 2010; 43(3):222–234.

24. Park JH, Jun EY, Kang MY, Joung YS, Kim GS. Symptom experience and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2009; 39(5):613–621.

25. Mazanec SR, Daly BJ, Douglas S, Musil C. Predictors of psychosocial adjustment during the post-radiation treatment transition. West J Nurs Res. 2011; 33(4):540–559.

26. Cheville AL, Beck LA, Petersen TL, Marks RS, Gamble GL. The detection and treatment of cancer-related functional problems in an outpatient setting. Support Care Cancer. 2009; 17(1):61–67.

27. Cha KS, Yoo YS, Cho OH. Stress and coping strategies of breast cancer patients and their spouses. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2012; 12(1):20–26.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download