Abstract

Purpose

Embarrassment is an unpleasant emotion that women undergoing Papanicolaou (Pap) tests often experience. These experiences differ according to individual, interactional and cognitive-emotional factors of embarrassment. This study was conducted to identify the factors influencing Pap test embarrassment (PapE) using a path analysis.

Methods

281 women who had Pap tests at four screening sites in G city completed questionnaires assessing the relationships among general characteristics, service locations, medical embarrassment (ME), and PapE. The data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 Package and LISREL 8.8 program.

Results

PapE was directly influenced by ME, and also both directly and indirectly affected by dispositional embarrassability and sexual experience, while only indirectly affected by psychological experience through ME. PapE concerning social face was both directly and indirectly affected by ME and dispositional embarrassability, while indirectly affected by both income and psychological experience. Only PapE and ME social judgement concern directly affected PapE concerning social face.

Figures and Tables

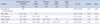

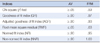

Table 2

Descriptive statistics of Embarrassability, Medical Embarrassment, and Pap Smear Embarrassment (N=281)

References

1. National Cancer Information Center. Gender differences in cancer incidence. Accessed April 15, 2014. http://www.cancer.go.kr.

2. National Cancer Information Center. Comparison of cancer incidence worldwide. Accessed April 15, 2014. http://www.cancer.go.kr.

3. National Cancer Information Center. 2012 Gender differences in cancer mortality. Accessed April 15, 2014. http://www.cancer.go.kr.

4. Waller J, Bartoszek M, Marlowand L, Wardle J. Barriers to cervical cancer screening attendance in England: a population-based survey. J Med Screen. 2009; 16:199–204.

5. Lee EJ, Park JS. Predictors associated with repeated papanicolaou smear for cervical cancer screening. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2013; 13(1):28–36.

6. Waller J, Jackowska M, Marlow L, Wardlea J. Exploring age differences in reasons for nonattendance for cervical screening: a qualitative study. BJOG. 2012; 119(1):26–32.

7. Park SJ, Park WS. Identifying barriers to papanicolaou smear screening in Korean women: Korean national health and nutrition examination survey 2005. J Gynecol Oncol. 2010; 21(2):81–86.

8. Chang SC, Woo JST, Yau V, Gorzalka BB, Brotto LA. Cervical cancer screening and Chinese women: insights from focus groups. Front Psychol. 2013; 4:48.

9. Kissal A, Beser A. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer early detection behaviors among elderly women. Int J. 2014; 7(1):157–168.

10. Guilfoyle S, Franco R, Gorin SS. Exploring older women's approaches to cervical cancer screening. Health Care Women Int. 2007; 28(10):930–950.

12. Park S, Chang S, Chung C. Contents analysis on cognitive-affective experiences in Pap smear participants. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2004; 8(1):37–48.

13. Logan L, Mcilfatrick S. Exploring women's knowledge, experiences and perceptions of cervical cancer screening in an area of social deprivation. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2011; 20:720–727.

14. Teng FF, Mitchell SM, Sekikubo M, Biryabarema C, Byamugisha JK, Steinberg M, et al. Understanding the role of embarrassment in gynecological screening: a qualitative study from the ASPIRE cervical cancer screening project in Uganda. BMJ Open. 2014; 4(4):e004783. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/4/4/e004783.full.pdf+html. Accessed June 11, 2014.

15. Kwok C1, White K, Roydhouse JK. Chinese-Australian women's knowledge, facilitators and barriers related to cervical cancer screening: a qualitative study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011; 13(6):1076–1083.

16. Fang DM, Baker DL. Barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer screening among women of Hmong origin. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013; 24(2):540–555.

17. Tung WC. Cervical cancer screening among Hispanic and Asian American women. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2011; 23(6):480–483.

18. O'Brien BA, Mill J, Wilson T. Cervical screening in Canadian First Nation Cree women. J Transcult Nurs. 2009; 20(1):83–92.

19. Augusto EF, Rosa MLG, Cavalcanti SMB, Oliveira LHS. Barriers to cervical cancer screening in women attending the family medical program in NiterÓi, Rio de Janeiro. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013; 287:53–58.

20. Cho EJ, Chung BY. Embarrassment; a concept analysis. J Korean Acad Adult Nurs. 2002; 14(2):276–286.

21. Cho EJ, Chung BY, Koo TB. Effect of desexualization care guided by dramaturgical interaction on women's embarrassment during cervical cancer screening. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2003; 9(4):351–368.

22. Cho EJ, Chung BY, Lee K, Consedine NS, Lee WK. Psychometric evaluation of uterine cervical cancer screening embarrassment questionnaire among Korean women: complementary use of Rasch model. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2011; 17(5):463–473.

23. Moettus A, Sklar D, Tandberg D. The effect of physician gender on women's perceived pain and embarrassment during pelvic examination. Am J Emerg Med. 1999; 17(7):635–637.

24. Cho EJ, Chung BY. A descriptive survey on women's embarrassability and embarrassment during cervical screening. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2002; 32(6):832–843.

25. Patton KR, Bartfiels JM, McErlean M. The effect of practitioner characteristics on patient pain and embarrassment during ED internal examinations. Am J Emerg Med. 2003; 1(3):205–207.

26. Goffman E. The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday Anchor Book;1959.

27. Henslin J, Biggs M. Dramaturgical desexualisation: the sociology of the vaginal examination. In : Henslin J, editor. Studies in the sociology of sex. New York: Appleton Century Crofts;1971. p. 136–160.

28. Consedine NS, Krivoddshekova YS, Harris CR. Bodily embarrassment and judgment concern as separable factors in the measurement of medical embarrassment: psychometric development and links to treatment-seeking outcomes. Br J Health Psychol. 2007; 12:439–462.

29. Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis. 4th ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc;1995.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download