Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to determine the prioritization of research topics by Korean oncology nurses.

Methods

A descriptive and cross-sectional survey was conducted via the website of the Korean Oncology Nursing Society, with participation sought by email from all of its members.

Results

Overall, 'pain' and 'quality of life' were the most important among the 74 topics, 'cancer prevention' was ranked 47th, while 'informatics' and 'telehealth' were ranked 62nd and 72nd, respectively. Korean oncology nursing research needs to be expanded to include community-based cancer prevention. In addition, research on informatics and telehealth in the oncology nursing area is necessary given the current dramatic changes in the implementation of information technology in medical services.

The incidence of cancer in Korea increased by 3.1% annually between 1999 and 2008,1) but the 5-year relative survival rate according to year of diagnosis improved notably from 44.0% during the period 1996-2000 to 59.2% during the period 2004-2008.2) With the change in the epidemiology of cancer, the concerns of health professionals or leaders have expanded to cancer prevention/early detection and long-term survivors dwelling in the community, in addition to the main areas of cancer treatment in clinics. Moreover, cancer patients and their families now require more specialized and individualized management in the processes of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation.3) These changes require a uniform approach from individual Korean oncology nurses.

In October 2000, oncology nurses and professors launched the Korean Oncology Nursing Society (KONS). The following year, the first issue of the Journal of the KONS was distributed (the title of this journal was changed to 'Asian Oncology Nursing' in 2011). Moreover, the educational qualification of advanced practice nurse (APN) in oncology was introduced as a formal master's course at graduate schools in nursing colleges in 2003. The certified APN in oncology qualification was authorized by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare in 2006, since when 316 APNs in oncology have graduated, and 102 APN candidates enrolled in Korean graduate schools.4)

The advent of the master's oncology APN qualification has provided important momentum to improvements in Korean oncology nursing research. According to the Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing,5) the major roles and tasks of APNs are to work as practitioners, researchers, educators, consultants/coordinators, and administrators; Oncology APNs must be involved in research.

Only 30 oncology nursing studies were published in the 1980s, but this number increased markedly to 214 in the period 1998-2003 and 391 in 2003-2008.6-8) This improvement was not only a quantitative one. While many early studies implemented descriptive or correlational research designs, more recent studies have focused on the effects of nursing interventions.9) Qualitative studies exploring the experiences of Korean patients with cancer also began to be published in the 2000s.9)

The circumstances surrounding oncology nursing have changed rapidly over the last 10 years, such that the KONS has been confronted with the need to set a new agenda for Korean oncology nursing research. As a basic step toward determining such new agendas, surveys on research priorities have been conducted in many countries. The US Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) has conducted such a study on research priorities every 4 years since 1981, and the results have been used for research agenda or basic data for funding resources for oncology nursing studies.10) Such studies have also been conducted with Canadian members of the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology,11) oncology nurses in West Australia12) and the Republic of Ireland,13) and Norwegian members of the Norwegian Society of Nursing in Cancer Care.14) Additional merits of studies into research priorities are the identification of research trends, supply of researcher information to help in the development of future research, and enhancement of communication regarding nursing research with government funding agencies and opinion leaders.15,16) The purpose of the present study was thus to elucidate the priorities of Korean oncology nursing research.

A descriptive study design was used to explore the nursing oncology research priorities of Korean oncology nurses.

The target population of this study was the 980 KONS members. The study questionnaire was distributed via the KONS website. With the society's help, its members were emailed the questionnaire survey on oncology nursing research priorities. The members who decided to participate in this survey downloaded the questionnaire file from the KONS website, completed it, and returned it to the KONS. Two weeks after the first email, the society sent further emails to its members to promote their participation. The collected questionnaires were first screened to check whether the participants had included personal information such as their email address or name; these were removed to guarantee their anonymity. The questionnaires were then delivered to the researchers. This study was approved by an institutional review board at a university.

The questionnaire used in this study to examine the prioritization of research was originally developed by Doorenbos et al.10) to explore the prioritization of research topics in oncology nursing of the ONS in the USA. It consists of 70 research topics in 5 research areas: Symptoms and side-effects, individual and family psychosocial and behavioral topics, health promotion, survivorship/palliative care/end of life, and health systems research. Additional questions asked respondents about their general characteristics and instructed them to select the perspective from which they were responding to the questions (i.e., oncology nurse, APN, or educator/researcher).

The questionnaire contents were composed based on the questionnaire used for a study in the USA about the research priorities of oncology nursing in the ONS in 200017) and 2004,18) and the ONS Research Agenda in 2005-2009.19) The question about each topic started with "How important is it to conduct research on each of the following..." and was answered using a 4-point Likert scale (from 'not at all' to 'high'). Permission was obtained from the authors to use the questionnaire developed in the USA, and it was translated into Korean using a translation and back-translation technique. Three professionals were then asked to add or delete any research topics that they considered especially pertinent or inappropriate/irrelevant to Korean circumstances, respectively. Four topics about hair loss, fever, change in body weight, and patient's adjustment were added.

A preliminary survey was conducted with five KONS members: An oncology nurse, an oncology APN, a researcher, an educator, and an administrator. The results of that survey suggested that writing medical terms in both Korean and English could facilitate understanding by the subjects about the questions because both languages are used in colleges and in clinical practice. Therefore, the research topics were written in both Korean and English.

In this study the Cronbach's alpha values of the questionnaire were .92, .91, .84, .83, and .75 for the subscales of 'symptoms and side effects,' 'individual and family psychosocial and behavioral,' 'health promotion,' 'survivorship, palliative care and end-of-life,' and 'healthcare systems,' respectively

Of the 980 KONS members, 164 returned the questionnaire; 3 cases were excluded because of missing data in over 70% of the questionnaire items, so that ultimately the data from 161 questionnaires were analyzed. Among the 980 members, a doctoral degree, master's degree, and bachelor's degree were held by 8.7% (n=85), 23.4% (n=229), and 67.9% (n=666), respectively; The respective rates for the 161 participants were 28.6% (n=46), 37.3% (n=60), and 34.2% (n=55), indicating a much higher proportion of respondents with a doctorate or a master's degree relative to for the KONS overall. Given that the participants' educational status could affect the research priorities of oncology nursing,10) the raw scores were weighted to adjust the sample size by the composition rate according to educational status. The weighting of the respondents with a doctorate was calculated by dividing the total number of KONS members with a doctoral degree by the number of participants with the degree; The weightings of those with a master's degree and a bachelor's degree were also calculated using the same method. The calculation of weights and the descriptive statistic analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows (version 16.0).

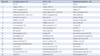

The response rate of this questionnaire survey was 16.7%. Nearly half of those surveyed were aged between 30 and 39years. The duration of nursing experience ranged widely from 2 to 40years, and 36.6% (n=59) had worked in oncology nursing for 5-9 years. A majority (57.1%, n=92) held a registered nurse (RN) license only, 18.0% (n=29) were RNs and APNs in oncology, and 5.6% (n=9) of those surveyed also held RN and APN USA oncology licenses. The current work setting of the largest number of the participants (24.2%, n=39) was a school of nursing, followed by a medical oncology unit (18.0%, n=29; Table 1).

When the respondents were asked to select the perspective from which they were responding to the questions, 28.6% (n=46), 28.0% (n=45), and 38.5% (n=62) chose educator/researcher, APN in oncology, and oncology nurse, respectively. The remaining respondents (n=8) did not answer this question.

The importance rating and the overall rank order of the 74 research topics are presented in Table 2. The scores of importance rating ranged from 2.01±0.73 (mean±SD) to 2.93±0.25 (of the possible range of 1-4). The top-20 topics were as follows:

a) Two topics of symptoms and side effect: pain and depression.

b) Eight topics of individual and family psychosocial and behavioral topics: quality of life, family adjustment to cancer, self-care, self-management, communication, coping, family functioning, and self-efficacy.

c) Three topics of health promotion: stress management, diet/nutrition, and screening/early detection.

d) Five topics of survivorship, palliative care and end-of-life: survivorship, palliative care, rehabilitation, cancer recurrence, and survivor wellness.

e) Two topics of healthcare systems research: quality improvement and continuum of care.

The prioritization of the top-20 research topics, recognized from the role perspectives of oncology nurses, APNs in oncology, and educators/researchers, are listed in Table 3. All three groups considered 'pain' to be the top priority. Oncology nurses perceived 'pain,' 'quality of life,' and 'stress management' to be the top three, in that order, while the oncology APNs ranked 'pain,' 'quality of life,' and 'continuum of care' as their top three. In contrast, while the researchers/educators also ranked 'pain' as the top research priority, they ranked 'survivor wellness' and 'fatigue' as the second and third priorities, respectively; These two topics were ranked very low by the oncology nurses and APNs.

Of the participants in this study, 77 (52.8%) were currently working in oncology clinics, 39 (24.2%) were teaching oncology nursing in colleges, and all had a doctorate in nursing. The remaining participants were enrolled as members of the KONS but were not currently working in oncology settings (Fig. 1). The top-10 research priorities of the participants who were currently working in nursing colleges vs. oncology clinics were explored (i.e., those not currently working in oncology settings were not examined). Participants working in nursing colleges highly ranked 'survivor wellness' and 'fatigue,' both of which were not ranked in the top-10 priorities by those currently working in oncology clinics. This suggests that the view of research priorities differed between participants working in nursing colleges and oncology clinics. In contrast, the top-10 priorities of APNs and RNs currently working in oncology clinics were similar (Fig. 1). Seven of the top 10 were common topics: 'pain,' 'quality of life,' 'stress management,' 'continuum of care,' 'family adjustment to cancer,' 'survivorship,' and 'self-care.'

This study explored the prioritization of oncology nursing research topics to provide a basis for the agenda for Korean oncology nursing research. The response rate for data collection via email from KONS members was 16.7%, which is markedly lower than that of 33.8% for a survey of research priorities conducted by general mail in the initial stage after launching the KONS.20) However, the present rate was slightly higher than that of a Web-based survey on research priorities in the USA, which had a 12% response rate.10) The lower response rate in this study compared to that of the previous Korean study in 2003 might be due to the different mode of administration of the questionnaire and the higher interest of the members in 2003 due to the KONS having just been launched at that time.

Fig. 2 compares the top-20 research priorities of oncology nursing between this study and that of the ONS in 2008.10) Only half of the top-20 topics overlap. 'Pain' and 'quality of life' were the most highly and commonly ranked research topics in both studies. In this study 'pain' was the top research priority of Korean oncology nursing. This may be due to the influence of a home visiting service program for community-dwelling cancer patients that was instigated by the Korean National Cancer Control Institute in 2009, for which pain management is the main service.21) This program was introduced in response to the 7.8% increase in the number of cancer patients in Korea between 2008 (178,816) and 2007 (165,942).22) This large increase was directly linked to the increase in the number of cancer patients dwelling in the community, which was in turn attributable to a higher rate of early patient discharge as a result of a hospital room turnover or medical expenses. This change may become a major concern to Korean oncology nurses as a new area of required research. Nevertheless, only 9.4% of all oncology nursing studies reported on between 2003 and 2008 in Korea explored the topic of pain.7)

'Quality of life' was ranked as the second priority for research in this study. Lee et al.23) searched three Korean research databases for studies on the quality of life of Korean cancer patients up to 2002. They found only 31 quantitative studies, and explained that the main reason for this dearth of studies conducted in Korea was the lack of reliable, valid, and culturally appropriate instruments capable of measuring the health-related quality of life of cancer patients. Subsequently, psychometric studies on cancer-specific quality-of-life instruments were conducted in Korean oncology nursing. One method of doing this was by culturally validating instruments developed for use in other countries [e.g., the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy: General (FACT-G), European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30, and Quality of Life Index-Cancer questionnaires].24) Another way was by the development of a cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire designed specifically for Korean patients.25) The latter was done from the perspective that Korean patients have a unique perception of quality of life.24) For example, a quantitative study found that Korean patients with cancer perceive 'maintaining well-being status' as a key factor influencing their quality of life. To maintain their well-being status, they care and manage their mind and bodies, and seek information. This is achieved mainly with the support of their spouses or direct/extended families, rather than from their friends.26) Cancer patients in Western countries place a higher emphasis on the support of their friends, which is why an item about friends is included in Western instruments measuring quality of life (e.g., FACT-G). Conversely, Korean patients with cancer tend to hide their diagnosis to friends, and they do not confide in them.26) Therefore, an instrument to measure cancer-related quality of life in Korean patients was developed.25)

Through these efforts toward psychometric evaluation, reliable and valid instruments measuring cancer-specific quality of life have been applied in oncology nursing studies with Korean patients. A review of Korean oncology nursing research between 2003 and 2008 revealed that 'quality of life' was the most frequently appearing keyword.8) A search of the KoreaMed research database, which was established by the Korean Association of Medical Journal Editors with the support of the Korean Academy of Medical Science, identified 53 Korean quantitative oncology nursing studies on quality of life published between 2009 and 2012 (www.koremd.org). Therefore, the term 'quality of life in cancer patients' is not only perceived as a major topic in the field of Korean oncology nursing, but it has also actually been studied. Doorenbos et al.10) emphasized that because 'quality of life' is a final outcome of cancer patient management, it continues to be an important topic of oncology nursing research. Similar to the findings of the present study, 'quality of life' was ranked as second in the list of research priorities in a Canadian study,11) and first in studies from Norway, The Netherland, and the USA.10,14,27) These results strongly suggest that quality of life is a major research topic in oncology nursing globally.

'Cancer prevention' was ranked top in the 2003 study on the research prioritization of Korean oncology nursing,20) but its ranking dropped to 47th in the present study. According to an analysis of Korean oncology nursing research, studies on cancer prevention comprised only 5.1% of all studies reported between 2003 and 2008.8) This concurs with the opinion of Lee et al.20) that the highest rank of cancer prevention in the 2003 survey reflects the influence of the governmental policy emphasizing cancer prevention in the initial stage of the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare's '10-year plan to conquer cancer.' The present study found that 'cancer prevention' ranked low among the research priorities. However, it remains critical in healthcare with respect to reducing the medical costs of cancer treatment and its management. Therefore, community-based studies for cancer prevention are required in future Korean oncology nursing research.

This study found that the rankings of 'informatics' and 'telehealth' were very low, at 62nd and 72nd, respectively (Table 2). This is broadly consistent with the findings of a survey in 2008 from the USA, in which they were ranked 69th and 66th, respectively.10) These low rankings may be attributable to the lack of recognition of the necessity of this research rather than their low importance as research topics. Current developments in information technology are producing new fields in the medical sector, such as telemedicine, e-health, or u-health. The Korean government is currently promoting a project to remotely monitor patients with chronic diseases, to provide counsel and a prescription service for them, and to evaluate its medical and economic validity.28) To enable oncology nursing practice to keep up with this trend, multidisciplinary oncology nursing research in cooperation with specialists in information technology should be initiated to validate the scientific basis of the practice.

A comparison of the prioritization of research topics by role perspectives revealed that oncology nurses, APNs in oncology, and researchers/educators all ranked 'pain' as the top research priority. However, the prioritization of other research topics by researchers/educators was quite different from those listed by oncology nurses or oncology APNs, while the priorities of the latter two were similar. For example, 'fatigue' was the outside the top-20 priorities recognized by oncology RNs or APNs, but was ranked third by the researchers/educators. In South Korea, studies on the fatigue of cancer patients were first conducted in the early 1990s. Such studies have been performed actively since 2000, most frequently by those exploring the symptoms of cancer patients. However, most of these studies have had a correlational design.8) Only 16 nursing intervention studies on cancer-related fatigue were conducted in Korea between 1990 and 2010. The most frequently studied intervention was foot/hand reflexo-massage followed by exercise (walking).29) This indicates the need to shift toward intervention studies based on the previous correlational studies on fatigue in Korean cancer patients. Researchers/educators may be more sensitive to the importance of this transition than oncology nurses or APNs in clinical practice. Therefore, researchers/educators might be expected to recognize 'fatigue' as a high priority.

The top-10 research priorities relative to the certification status of the nurses working in oncology clinics (i.e., APN vs. RN) were similar in this study. The oncology APN system does not have much of a history in Korea, only being authorized as a qualification in 2006. Therefore, it might be expected that their research priority perspectives would be similar. According to the recent job analysis of Korean oncology APNs, 'implementation of research' was reported as the most difficult task of all 66 expected of them, and 'present research results' was noted to be one of most infrequently performed tasks. In clinical research, the role of both Korean oncology APNs and RNs is mainly to assist medical research rather than to conduct their own nursing research.30) In the future, oncology APNs need to place more emphasis on oncology nursing research or to collaborate in multidisciplinary studies with their coworkers. To this end, the oncology APN course curriculum at graduate schools should emphasize research methodology and statistics.

According to Oh,8) only 17.9% of Korean oncology nursing studies were funded research. This is a very low proportion compared to Molassiotis et al.15) who performed a search of Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature database-finding that 48.4% of the 619 oncology nursing studies had received research funding. Therefore, greater financial support for active Korean oncology nursing research is urgently needed. In this context, the results of the present study represent important information for research funding agencies or institutions with respect to setting the priorities of oncology nursing research. In addition, these results could be used as basic data for the KONS to establish policies guiding the direction of future research.

Overall, 'pain' and 'quality of life' were the most highly ranked oncology nursing research topics, while 'cancer prevention' was ranked lowest, and 'telehealth' and 'informatics' also had very low ranks . Korean oncology nursing research needs to be expanded to community-based cancer prevention. In addition, research on informatics and telehealth in the oncology nursing area is necessary given the current dramatic changes in the implementation of information technology in medical services. These findings may contribute toward the development of a Korean oncology nursing research agenda and the provision of information to funding agencies with respect to setting the priorities of oncology nursing research.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Top-10 Research Priorities According to The Types of Current Work Setting (Nursing College vs. Oncology Clinic) and Certification (APN vs. RN Working in Oncology Clinic).

APN=advanced practice nurse; RN=registered nurse.

|

| Fig. 2Top-20 Research Priorities of the Korean Oncology Nursing Society (KONS) and the US Oncology Nurses Society (ONS) in 2008 |

Table 1

Characteristics of the Respondents among the Members of the Korean Nursing Society (ONS) (N=161)

References

1. National Cancer Center. Annual Report of Cancer Statistics in Korea in 2008. Accessed June 8, 2011. http://www.ncc.re.kr/english/infor/kccr.jsp.

2. Jung JW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Park EC, Lee JS, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2003. Cancer Res Treat. 2011; 43:1–11.

3. Lee ER, Kwak MK, Kim EJ, Kwon IG, Hwang MS. Job analysis of Korean oncology advanced practice nurses in clinical workplace: using the DACUM method. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2010; 10:68–79.

4. Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing. Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education. Accessed June 8, 2011. http://kabon.or.kr/kabon04/index02.php.

5. Korean Accreditation Board Nursing. Role and Core Confidency. Accessed December 12, 2012. http://www.kabon.or.kr/kabone04/index03.php.

6. Choi SH, Nam YH, Ryu EJ, Baek MW, Suh DH, Suh SR, et al. An integrative review of Oncology Nursing Research: 1980-1998. J Korean Acad Nurs. 1998; 28:786–800.

7. Oh PJ. An integrative review of oncology nursing research in Korea: 1998-2003. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2003; 3:112–121.

8. Oh PJ. An integrative review of oncology nursing research in Korea: 2003-2008. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2010; 10:80–87.

9. Chung BY, Yi MS, Choi EH. Trends of Nursing Research in the Journal of Oncology Nursing. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2008; 8:61–66.

10. Doorenbos AZ, Berger AM, Brohard-Holbert C, Eaton L, Kozachik S, LoBiondo-Wood G, et al. 2008 ONS research priorities survey. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008; 35:E100–E107.

11. Bakker DA, Fitch MI. Oncology nursing research priorities: a Canadian perspective. Cancer Nurs. 1998; 21:394–401.

12. Barrett S, Kristjanson LJ, Sinclair T, Hyde S. Priorities for adult cancer nursing research: a West Australian replication. Cancer Nurs. 2001; 24:88–98.

13. Murphy A, Cowman S. Research priorities of oncology nurses in the Republic of Ireland. Cancer Nurs. 2006; 29:283–290.

14. Rustøen T, Schjølberg TK. Cancer nursing research priorities: a Norwegian perspective. Cancer Nurs. 2000; 23:375–381.

15. Molassiotis A, Gibson F, Kelly D, Richardson A, Dabbour R, Ahmad AM, et al. A systematic review of worldwide cancer nursing research: 1994 to 2003. Cancer Nurs. 2006; 29:431–440.

16. Kim MJ, Oh EG, Kim CJ, Yoo JS, Ko IS. Priorities for nursing research in Korea. J Nurs Scholarship. 2002; 34:307–312.

17. Ropka ME, Guterbock T, Krebs L, Murphy-Ende K, Stetz K, Summers B, et al. Year 2000 oncology nursing society research priorities survey. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002; 29:481–491.

18. Berger AM, Berry DL, Christopher KA, Greene AL, Maliski S, Swenson KK, et al. Oncology nursing society year 2004 research priorities survey. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005; 32:281–290.

19. Berry DL. Oncology Nursing Society 2005-2009 Research Agenda. 2011. Accessed Feburary 11, 2011. http://www.ons.org/research/information/documents/pdfs/ONSResAgendaFinal10-24-07.pdf.

20. Lee EH, Kim JS, Chung BY, Bok MS, Song BE, Kong SW, et al. Research priorities of Korean oncology nurses. Cancer Nurs. 2003; 26:387–391.

21. Choi SY, Chang KO, Park MN, Ryu E. Pain management in cancer patients who are registered in public health centers. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2012; 12:77–83.

22. The Korean Central Cancer Registry, National Cancer Center. 2008 Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2010.

23. Lee EH, Park HB, Kim MW, Kang S, Lee HJ, Lee WH, et al. Analyses of the studies on cancer-related quality of life published in Korea. J Korean Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2002; 20:359–366.

24. So HS, Lee WH, Lee EH, Chung BY, Hur HK, Kang ES, et al. Validation of quality of life index-cancer among Korean patients with cancer. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2004; 34:693–701.

25. Lee EH. Development and psychometric evaluation of a quality of life scale for Korean patients with cancer (C-QOL). J Korean Acad Nurs. 2007; 37:324–333.

26. Lee EH, Song YS, Chun MS, Oh KS, Lee WH, Lee YH. Quality of life cancer patients: grounded theory. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2004; 4:71–81.

27. Ambaum B, Courten A, Fliedener M. Research priorities in oncology nursing in the Netherlands. In : Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Cancer Nursing; 1996 Aug 12-15; Brighton, UK. Vancouver: International Society of Nurses in Cancer Care;1996.

28. Lee Y, Park J, Park D, Ryu S. Comprehensive evaluation of u-health trial project. Seoul: Korea Health Industry Development Institute;2008.

29. Oh PJ, Jung JA. A meta analysis of intervention studies on cancer-related fatigue in Korea: 1990-2010. J Korean Clin Nurs Res. 2011; 17:163–175.

30. Lee ER, Kwak MK, Kim EJ, Kwon IG, Hwang MS. Job Analysis of Korean Oncology Advanced Practice Nurses in Clinical Workplace: Using the DACUM Method. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2010; 10:68–79.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download