INTRODUCTION

The main goal of effective orthodontic treatment is to improve a patient's esthetic and dentofacial function. In addition, two issues that are of particular concern to adult patients are esthetics and treatment time. To this end, the primary aim across all areas of orthodontics has been the investigation of new approaches that can increase orthodontic treatment efficiency while shortening the treatment time, thereby facilitating the therapeutic process without foregoing optimal results.

1 An example of this is the popularity of treatments using removable clear aligners that help achieve superior esthetics, comfort, and oral hygiene compared to traditional appliances; however, their use is limited to selected cases.

2

A recent systematic review that evaluated the effectiveness of interventions in accelerating orthodontic tooth movement suggested that corticotomy is a relatively safe and effective intervention.

3 Although corticotomy is effective, it has been associated with significant postoperative discomfort.

45 Moreover, the invasive nature of these interventions, e.g., the elevation of the mucoperiosteal flaps and length of surgery, has resulted in the patients as well as the dental community showing reluctance in employing such methods.

5

This report describes a specific intervention to solve moderate crowding of both the arches by combining the use of an innovative, computer-guided

67 piezocision procedure and esthetic clear aligners.

DIAGNOSIS AND ETIOLOGY

A healthy, 23-year-old, Caucasian woman was referred to the Department of Orthodontics of Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, to undergo evaluation for the possibility of a short and esthetic orthodontic treatment for crowding. The patient's medical history was unremarkable except for a previous unsuccessful orthodontic treatment involving the extraction of the maxillary right first premolar and mandibular left lateral incisor. Extraoral examination revealed good facial proportions with a convex profile, competent lips, and smile line, which followed the curvature of the lower lips (

Figure 1). She had no temporomandibular joint (TMJ) symptoms and radiographic examinations including panoramic radiography and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), did not reveal any alterations to the TMJ. Pretreatment intraoral and dental cast examinations demonstrated a tendency for a Class II molar and Class III canine relationship on the right side and Class I molar and canine relationship on the left side (

Figure 1). The overjet was 6.1 mm, and the overbite was 5.7 mm. The maxillary dental midline was deviated by 1.5 mm towards the facial midline because of previous extraction of the maxillary right first premolar, and the mandibular dental midline was deviated by 1.5 mm towards the right side of the maxillary dental midline (

Figure 1).

The patient displayed moderate crowding of both the arches (maxilla, 5 mm; mandible, 6 mm). Panoramic and lateral cephalometric radiographs were acquired before treatment (

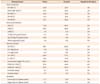

Figure 2), and these revealed no caries, root resorption, dental abnormalities, and traumatic and pathologic lesions in the alveolar crests and the site of endodontic treatment of the maxillary left first molar. The cephalometric analysis demonstrated a Class II skeletal relationship (A-point−nasion−B point [ANB], 5.4°) with a normodivergent growth pattern (sella-nasion plane to mandibular plane angle, 43°) (

Table 1,

Figure 3). The patient was periodontally healthy, but showed a thin gingival biotype with Miller Class I defects on the maxillary left lateral incisor, canine and first premolar, and also on maxillary right lateral incisor and canine (

Figure 1). Bleeding on probing (BOP) and probing pocket depth (PPD) were evaluated using a UNC 15 probe (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA) and were measured using a standardized force probe (about 0.25 N) at the mesiobuccal, midbuccal, distobuccal, distolingual, midlingual, and mesiolingual aspects in both the arches from the left first molar to the right first molar. The BOP and PPD measurements were recorded, for each jaw, before oral surgery (T0), at 4 months (T1), at the end of treatment (T2), and at the 2-year retention follow-up (T3). Each measurement was repeated twice by the same operator, and the values were averaged. Oral healthrelated quality of life (OHRQoL) was assessed using the Italian version of the short-form oral health impact profile with 14 questions (OHIP-14), which represents the following seven dimensions of OHRQoL: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap.

5 The patient was instructed in the use of the questionnaire, which was filled out preoperatively (T0), 3 days after surgery, 7 days after surgery, at the end of orthodontic treatment (T2), and at the 2-year retention follow-up (T3). Responses were based on an ordinal 5-point adjectival scale (0 = never; 1 = rarely; 2 = occasionally; 3 = fairly often; and 4 = very often). OHRQoL was characterized by the summary scores of the OHIP-14, with higher scores indicating a stronger negative influence on OHRQoL. The initial (T0) OHIP-14 score was compared with the 3- and 7-day postoperative scores in order to determine the influence of this surgical technique on OHRQoL. The (T0) OHIP-14 score was then compared with the score at the end of therapy (T2) and at the 2-year retention follow-up (T3) to evaluate the influence of the present combined treatment on OHRQoL.

RESULTS

The total treatment duration was 8 months (1 month for the maxillary arch and 8 months for the mandibular arch). At the end of treatment, a bilateral Class I molar and Class I canine relationship were obtained. The maxillary and mandibular arches were well aligned (

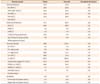

Figure 7). The posttreatment lateral cephalometric radiograph and the superimposition of the lateral cephalometric radiographs acquired before and after treatment showed no significant changes (

Table 2,

Figure 8).

Because of the diligent use of the retainer, at the 2-year retention follow-up visit, the alignment of the maxillary and mandibular teeth was stable (

Figure 9). The posttreatment study models at the end of the orthodontic therapy and at the 2-year follow-up were superimposed using a software (Magics; Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). No relapse was seen with the exception of a minimum deviation (0.15 mm) of the maxillary right central incisor and mandibular right lateral incisor (0.15 mm). Pretreatment gingival recession recordings were unchanged, and no periodontal pocket formation or dentin hypersensitivity was observed. In addition, good preservation of the interdental papillae with no gingival recession was evident.

Table 3 shows the mean PPD values and BOP rates in the maxillary and mandibular arches at all time points.

Panoramic radiographs acquired after treatment and at the 2-year retention follow-up showed no significant reduction in the radiographic height of the crestal bone and no evidence of any significant apical root resorption. This evidence was supported by the posttreatment CBCT findings that revealed no changes in the alveolar bone when compared to the pretreatment CBCT findings (

Figure 10).

The OHIP-14 filled out by the patient before the treatment (T0), and 3 and 7 days after surgery had a total score of 11 points (T0 = 1; 3 days after surgery = 10; and 7 days after surgery = 0). A deterioration in OHRQoL was observed only after 3 days of surgery. An improvement in OHRQoL was also observed at the end of therapy (OHIP-14 = 0) than at the beginning of therapy (OHIP-14 = 1). The improvement in OHRQoL was also confirmed at the 2-year retention follow-up (OHIP-14 = 0).

DISCUSSION

In addition to the professional's considerations regarding the appropriateness and effectiveness of a treatment plan, addressing the adult patients' two most frequent demands for a reduction in treatment time and improved esthetics are a goal in the management of malocclusion.

2 In the case study described above, both surgical as well as orthodontic techniques were combined to meet those goals. The following paragraphs discuss both the surgical choices made, as well as the orthodontic approach adopted for treatment.

Corticotomy involves selective alveolar decortications in the form of lines and dots performed around the teeth that need to move. It is done to induce a state of increased tissue turnover and transient osteopenia, which is followed by a faster rate of orthodontic tooth movement.

5 In the present technique, the osteotomy cuts were performed using a piezosurgical microsaw without raising a mucoperiosteal flap.

6 The piezosurgical microsaw comes into contact with the soft tissue without causing damage.

678 While corticotomy is an accepted method to accelerate tooth movement, traditional techniques have often been considered rather invasive.

9 As described in the scientific literature, traditional corticotomy techniques imply full-thickness flap elevation, corticotomy cuts, and elective bone grafting.

49 These procedures are often time consuming (3 to 4 hours long), require oral and/or intravenous sedation, and carry undeniable postoperative morbidity and periodontal risks for the patient.

101112 Dibart et al.

1011 have popularized the concept of “piezocision”— a procedure that entails small incisions, minimal piezoelectric osseous cuts to the buccal cortex alone, and minimal bone or soft-tissue grafting.

More recently, Milano et al.

13 described a method for combining piezocision with computed tomography. After creating a 3D model of the arch, the corticotomies are planned and transferred to a resin surgical guide by using a numerically controlled milling machine. The main disadvantage of this technique is the laboratory phase, which could cause an error. Furthermore, the surgeon must add resin to stabilize the guide during surgery.

13 Unlike in the other previously described flapless corticotomy techniques, in the present technique, the cuts were made using a 3D-printed surgical guide that reduced the risk of damage to the anatomical structures. The possibility of virtually planning the incisions provides a safer means to selectively cut the bone and facilitate the preservation of root integrity. Indeed, in some interdental sites, the design and performance of corticotomy can be based on direct visualization of the crown (as well as the corresponding imaginary longitudinal axis of the tooth), together with the tactile sensation of the interdental concavity between the root prominence.

14 However, when limitations such as root proximity, root convexity, or abnormal root angulations are present, the use of a surgical guide is the only way to maximize root safety.

67 Moreover, although full-flap elevation does entail increased morbidity for the periodontium, it does not add to the safety or precision of the procedure because tooth roots are still concealed by the cortical bone.

An adjunctive treatment to corticotomy described in the literature is alveolar augmentation with a demineralized bone graft to cover any fenestration and dehiscence, and to increase the bony support for both the teeth and the overlying soft tissues.

4 However, there is no evidence that bone grafting of the alveolus enhances the stability of the orthodontic result,

15 and in the present case, a piezocision technique, without bone grafts, was used successfully.

The potential repercussions of corticotomy on the periodontium must be evaluated.

67 It is imperative that an accurate periodontal diagnosis is established before treatment initiation and that periodontal checkups are regularly performed after surgery and throughout the period of orthodontic movements.

2 If periodontal disease is diagnosed at baseline evaluation, it must be appropriately treated and stabilized before commencing any orthodontic treatment. The present technique seems particularly indicated in adults with gingival recessions and a thin gingival biotype, because it does not interfere with the marginal periodontium, involves significantly less trauma to the periodontal tissues, and does not involve hard or soft-tissue grafting. In the present case, the patient showed good maintenance of interdental papillae, a reduction of PPD values, no reduction in crestal bone height, and no evidence of root damage at the end of the orthodontic treatment and at the 2-year follow-up. The improvement in the periodontal indices was stable because good oral hygiene could be maintained when the teeth were well aligned.

When responding to a traumatic stimulus, bony tissues initially pass through a biological stage called regional acceleratory phenomenon (RAP), which is characterized by a transient increase in bone turnover and a decrease in trabecular bone density.

16 Recent studies suggest that the length of RAP is approximately 4 months.

15 In view of this time limit and in line with the findings of other researchers,

23456 the orthodontic treatment in the present case was started immediately after surgery.

Moving on to the orthodontic approach adopted, it was possible to complete the treatment in approximately one-third the time needed for the conventional orthodontic treatment, by combining the use of computer-guided piezocision and clear aligners. In this case, each aligner was retained for 5 days, rather than 15 days, for correcting the malocclusion and moderate crowding.

17 The corticotomy procedure has been reported to shorten the conventional orthodontic treatment time, and authors have claimed that teeth can be moved 2 to 3 times faster.

24 The current case findings confirm the previously published findings

24 and support this treatment option.

Currently, the long duration of a fixed orthodontic treatment may entail higher risks of caries and external root resorption, thereby decreasing patient compliance.

2 Clear aligners are relatively invisible, easy to insert and remove, and comfortable to wear. In the present case, the use of clear aligners resulted an improvement in the periodontal indices, with a relevant reduction of PPD in the lower jaw. This result may be attributed to the possibility of removing the clear appliance during oral hygiene, and to the effect of a reduced treatment time.

Nevertheless, clear aligners have some drawbacks. Djeu et al.

18 conducted a retrospective study comparing clear aligners with fixed orthodontic treatment. They found that esthetic clear aligners were especially deficient in their ability to correct anteroposterior discrepancies and occlusal contacts, thus demonstrating their limitation in overjet correction. Regarding the overbite value, Kravitz et al.

19 stated that the average true intrusion obtained using aligners in non-growing subjects was lower than the one obtained using the segmented arch technique. This may explain the minimal overbite correction observed in the present case (from 6.1 to 5.7 mm).

In terms of the effectiveness and appropriateness of using clear aligners, corticotomy speeds up the treatment and increases the scope of bone injury due to tooth movement, which, in turn, will initiate the previously mentioned RAP. This dynamic process, with its accompanying spurt of local activity (i.e., bone remodeling and surges in osteoclastic and osteoblastic activity), induces a state of transient osteopenia responsible for rapid tooth movement, because the teeth are moving in a more “pliable” environment.

10 As stated by Wilcko et al.,

9 given that corticotomy creates a more pliable bone, a fixed orthodontic wire might produce too strong an effect. When corticotomy is used to achieve faster orthodontic movement, the use of a clear aligner seems to be more appropriate to obtain greater control over orthodontic movement without the risk of losing the anchorage.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download