Abstract

Objective

Methods

Results

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

The experimental set-ups used in this study.

Figure 4

A comparison of frictional forces among the 7th Generation (7G), STb, and In-Ovation L (IO) groups. A, The control group (no displacement); B, a 2-mm palatal displacement of the maxillary right lateral incisor (MXLI); and C, a 2-mm gingival displacement of the maxillary right canine (MXC).

Figure 5

A comparison of frictional forces among the control group (no displacement), a 2-mm palatal displacement in the maxillary right lateral incisor (MXLI) group, and a 2-mm gingival displacement in the maxillary right canine (MXC) group. A, 7th Generation (Ormco, Orange, CA, USA); B, STb (Ormco); and C, In-Ovation L (GAC, Dentsply Corp., York, PA, USA).

Figure 6

A comparison of original (solid lines) and effective slot dimensions (dotted lines) of brackets with a 2-mm gingival displacement of the maxillary right canine. From the left side, the 7th Generation (Ormco, Orange, CA, USA), STb (Ormco), and In-Ovation L brackets (GAC, Dentsply Corp., York, PA, USA) are shown.

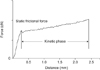

Figure 7

Wire deflection from a 2-mm gingival displace ment of the maxillary right canine and 2-mm palatal displacement of the maxillary right lateral incisor.

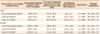

Table 2

Static and kinetic frictional forces (cN) from a 2-mm palatal displacement of the maxillary right lateral incisor and 2-mm gingival displacement of the maxillary right canine

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

7th Generation (7G) and STb: Ormco, Orange, CA, USA; In-Ovation L (IO): GAC, Dentsply Corp., York, PA, USA.

*One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); †Welch's variance-weighted ANOVA; ‡multiple comparison test was performed using Tukey's HSD; §multiple comparison test was performed using Dunnett's T3.

PD, Palatal displacement; MXLI, the maxillary right lateral incisor; GD, gingival displacement; MXC, the maxillary right canine.

Table 3

Comparisons of static and kinetic frictional forces according to displacement type

PD, Palatal displacement; MXLI, the maxillary right lateral incisor; Control, no displacement; GD, gingival displacement; MXC, the maxillary right canine.

*One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); †Welch's variance-weighted ANOVA; ‡multiple comparison test was performed using Tukey's HSD; §multiple comparison test was performed using Dunnett's T3.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download