INTRODUCTION

Johnston et al.

1 defined retention as the phase of orthodontic treatment that maintains teeth in their orthodontically corrected positions following the cessation of active orthodontic tooth movement. To minimize or prevent a relapse, almost every patient who has had orthodontic treatment is given some type of retainers.

2 This is vital for successful orthodontic treatment, as the post-treatment stability of any corrected malocclusion is unpredictable.

3 The goal of orthodontic retention is to increase the stability of the dentition after orthodontic treatment.

3

A study by Renkema et al.

2 showed that factors such as pre-treatment conditions, post-treatment occlusion, the end result, and oral hygiene determine the choice of retainer used. Based on a survey done by Keim et al.

4 in the United States of America, the Hawley retainer is still the most commonly used retainer, although this trend was decreasing. Retainers bonded on the maxillary and mandibular arches are preferred by orthodontists in the Netherlands,

2 while in Australia and New Zealand, an upper clear retainer and lower canine-to-canine bonded retainer are commonly used.

5

The objectives of this study were to identify the types of retainers that are commonly used and to investigate the variations in retention practice among orthodontists in Malaysia. Currently, no research has been conducted on the retention practices among orthodontist in this country and in the Asian Pacific region, and it is not known whether the retention practices in this country are similar to those in other developed countries. The insights provided by this study allow for development of proper clinical guidelines regarding orthodontic retention protocols. Thus, it can be a standard reference and guideline for clinicians in order to reduce the patient's burden in wearing the retainer in order to combat relapse and enhance the stability after active orthodontic treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted via a questionnaire consisting of 25 multiple-choice questions modified from Pratt et al.

6 and Valiathan and Hughes.

7 The questionnaire was divided into three parts. The first part gathered background data of the individual orthodontists. Several identifiers were included in order to classify the respondents into subgroups. These identifiers were age, gender, state of current practice, practical setting, and year of graduation from the orthodontic program. The second part consisted of questions involving the types of retainers that were commonly prescribed. The third part involved questions about retention practice, patient's compliance, and retention check-up. This questionnaire was first distributed to 10 randomly selected orthodontists for surface validation before conducting the final survey.

Full lists of the names and addresses of orthodontists were obtained from the Malaysian Association of Orthodontists website. In order to calculate the required sample size and power of the study, a formula based on a study by Kish

8 was used (sample size calculation = n / [1 - (n / population)]. Therefore, to obtain a sample of n = 58 responses with 99% confidence and accounting for a 60% response rate, 97 samples were required for this survey. A simple random sampling method was used by drawing the name lots of the registered members. A total of 97 registered orthodontists were included in this study. The study participants were orthodontists registered with the Malaysian Association of Orthodontists who are currently practicing in this country, whereas expatriate orthodontists and general dental practitioners who practice as orthodontics were excluded.

The questionnaire was sent to the selected orthodontists as hard copies along with a self-addressed stamped envelope in June 2014. The survey was concluded 2 months after the initial mailing, whereby any response after that period was not included. Confidentially of the information provided was assured and participation was voluntary.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (USM/JEPeM/1405206).

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) to derive descriptive statistics. The items were all described in percentages.

RESULTS

A total of 32 respondents sent completed questionnaires within 2 months after the initial mailing. This included 12 male and 20 female respondents. Most of the responding orthodontists (59.4%) practiced in a government setting and 40.6% worked in the private sector. Of the 32 orthodontists, 4 had graduated from the orthodontic program between 1980 and 1990, 13 between 1990 and 2000, and the remaining 15 orthodontists graduated after 2000. Of the 32, 87.5% had at least 6 years of experience as an orthodontist. More than half (59.4%) of responding orthodontists debonded fewer than 100 cases in year 2014.

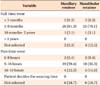

The vacuum-formed retainer was the most commonly used retainer for both maxillary (46.9%) and mandibular (46.9%) arches, followed by the Hawley retainer (maxilla, 43.8%; mandible, 37.5%), and the fixed retainer (maxilla, 3.1%; mandible, 9.4%) (

Table 1). The orthodontists mostly fabricated maxillary retainers (81.3%) in the office laboratory, rather than in the commercial laboratory; these results were similar for mandibular retainers (84.4%).

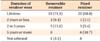

More than two-third of the orthodontists prescribed full-time maxillary retainer wear for more than 20 h per day to their patients, and 81.3% of orthodontists instructed the patients to wear the retainers for at least 3–9 months (

Table 2). Mandibular retainer wear prescription was similar, i.e., 71.9% prescribed full-time wear and 78.1% prescribed a full-time retention period of 3–9 months (

Table 2). Most of the orthodontists who prescribed part-time wear of the retainer also instructed their patients to wear the retainers for 9–16 h per day (maxillary, 59.4%; mandibular, 56.3%). None of the orthodontists allowed the patient to decide the amount of time the retainer should be worn (

Table 2).

Upon survey, a total of 90.6% of the orthodontists prescribed removable retainers to 75–100% of their patients, whereas 78.1% prescribed fixed retainers to 0–25% of their patients (

Figure 1). The majority of the orthodontists disagreed that pre-orthodontic extraction influenced the type of retainer prescribed during the retention phase. The patient's age was considered an influential factor in terms of compliance to retainer wear by 78.1% of the orthodontists (

Figure 2).

Generally, most of the orthodontists preferred their patients to wear retainers indefinitely (removable, 71.9%; fixed, 68.8%). Only 15.6% told their patients that they could stop wearing removable retainers 2–5 years after debonding, followed by 9.4% at 2 years or less after debonding (

Table 3). This result correlated with the retention period, whereby 53.1% of the orthodontists prescribed a retention period of more than 6 years. This was followed by a retention period of 2 years or less (31.3%), 2–4 years (9.4%), and lastly, 4–6 years (6.3%). This study showed that almost half (43.8%) of the patients returned for retainer-checking appointment up to 1 year, followed by 40.6% who came for 2–4 years, and 9.4% returned for 4–6 years. Only 6.3% returned to have their retainers checked for more than 6 years (

Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

Only about one-third (33%) of the randomly selected orthodontists responded to the questionnaire. This resulted in a confidence level of only 90%, instead of 99% as originally targeted. The response rate in this study was similar to the study by Valiathan and Hughes in 2010.

7 That survey was based on a study aimed at identifying common retention practices in the United States, in which an overall response rate of 32.9% was achieved. The response rate in this present study was markedly better than that in a study conducted by Pratt et al.

6 whose objective was to evaluate protocols and trends in orthodontic retention involving practicing members of the American Association of Orthodontists in the United States. In that study, the response rate obtained was 18%, which was lower than our response rate. However, when compared to other related studies, the overall response rate (ranging from 61% to 91%)

29101112 was higher than that in our study. The reason for the poor response from the orthodontists in our study could be they were not keen to take part in research due to their busy schedule, not receiving the questionnaire because they had moved to new offices, or the allocation of only two months for the completion of this survey.

The results of this study showed that vacuum-formed retainers were the most commonly prescribed maxillary and mandibular retainers. This finding was in agreement with the recent study conducted by Meade and Millett.

10 That study aimed to evaluate retention protocols and the use of vacuum-formed retainers among specialist orthodontists in the Republic of Ireland, which involved 123 eligible Members of the Dental Council of Ireland Specialist Register of Orthodontists and/or the Orthodontic Society of Ireland. They found that vacuum-formed retainers were the most commonly chosen retainers, prescribed by 53% of respondents for the maxilla and 33% for the mandible. Moreover, our study findings were also in line with those of a study conducted by Singh et al.

9 in 2009 on the orthodontic retention pattern in the United Kingdom, which showed that vacuum-formed retainers were the most commonly used in the National Health Services and hospital practice. However, our results were in contrast to those obtained in other studies conducted in the Netherlands,

2 Australia,

5 New Zealand,

5 Norway,

11 and Switzerland.

12 In Netherlands and Switzerland, the most commonly used retainers for both types of arches were bonded retainers. Maxillary invisible retainers and mandibular canine-to-canine bonded retainers were the retainer of choice of orthodontists in Australia and New Zealand. Norwegian orthodontists preferred to use a combination of fixed and removable retainers (clear thermoplastic retainer) for the maxillary arch and fixed retainers for the mandibular arch during the retention phase after active orthodontic treatment.

It is worth mentioning that the results we obtained showed that the prescription of the Hawley retainer did not differ much from that of the vacuum-formed retainer. We found that the use of the Hawley retainer was the second most popular among orthodontists in this country. Based on a survey done by Keim et al.

4 in the United States of America, the Hawley retainer remained the most commonly used retainer, although the trend was decreasing. Another survey by Pratt et al.

6 also showed that for the maxillary arch, the Hawley retainer was most frequently used (47%), followed closely by the vacuum-formed retainer (41%). Valiathan and Hughes

7 also concluded that the Hawley retainer is the most commonly retainer used for the upper arch.

A very small number of orthodontists still used fixed retainers in their practice and the use of a mandibular fixed retainer

4 was higher than for a maxillary fixed retainer. A survey carried out by Wong and Freer

5 showed that the fixed retainer was used by a small number of orthodontists (maxillary, 3.1%; mandibular, 9.4%), which was similar to the results of the present study. However, fixed retainers (42%) were used most frequently for the mandibular arch, followed by the Hawley retainer (29%), and the vacuum-formed retainer (29%).

6 The findings from the studies by Keim et al.

4 and Pratt et al.

6 were in contrast to the results obtained in this study, indicating that there was a variation in the use of the retention appliances in different countries. The choice of retention appliances used by orthodontists may be based on the ease of fabrication, aesthetics, pattern of extractions, oral hygiene,

2 compliance of the patient, durability, pre-treatment occlusion, or situation,

210 post-treatment occlusion,

2 orthodontists personal preference,

512 clinical experiances,

11 specialist status,

1314 as well as the cost, rather than popularity.

Orthodontists in the Netherlands differed in their opinions on the length of time that retainers should be worn and on the duration of the retention phase.

2 Patients were advised to wear the removable retainers for an average of 18 h per day, 7 days a week, after which part-time wear was advised for 9–16 h a day. Similar to their first retention phase, we found that two-thirds of the orthodontists prescribed full-time maxillary retainer wear, for more than 20 h per day, for at least 3–9 months. The majority of orthodontists in this country practiced a retention period of 6 years and more, and generally preferred their patients to wear the retainers for a lifetime. This was in agreement with the recent study by Meade and Millett

10 who found that lifetime wear of retainers was advised by 67–78% of orthodontists in Ireland. Only a small percentage of Malaysian orthodontists (15.6%) told their patients that they could stop wearing removable retainers 2–5 years after debonding. Overall, most of the orthodontists scheduled the first retention appointment at 1–3 months after debonding and followed their patients closely for a maximum of 2–4 years. The timing of the scheduled retention appointments varied among clinicians, and depended on their number of years in practice, the volume of patients debonded, and the type of retainer prescribed.

7

Histological studies have shown that reorganization of the periodontal ligament occurs over a 3–4-month period after cessation of orthodontic tooth movement, reorganization of the gingival tissue occurs over a 5– month post-treatment period, and the gingival collagen fiber network typically takes 4–6 months to remodel, while the supracrestal periodontal fibers remained stretched and displaced for more than 232 days after cessation of orthodontic tooth movement.

1415 This suggests that the retention period should generally last at least 7 months.

1 In this respect, results from our study showed that the retention practice among orthodontists in this country was in line with the suggestion by Johnston et al.,

1 in order to minimize relapse and to enhance stability.

The limitation of this study was that the respondents were not classified into subgroups when data was analyzed. Classification of the respondents by parameters such as gender, age, year of graduation, clinician preference, and others may have provided a clearer picture. However, the current findings can act as a primary guideline to orthodontists in this country for patient management after active orthodontic treatment in their clinical setting. Considering the cost of orthodontics treatment and the typically long waiting list for orthodontic treatment in most governmental settings, retreatment of cases is not likely to be feasible. Further research into the long-term effectiveness of individual retention protocols is needed.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download