Abstract

In the present report, we describe the successful use of miniscrews to achieve vertical control in combination with the conventional sliding MBT™ straight-wire technique for the treatment of a 26-year-old Chinese woman with a very high mandibular plane angle, deep overbite, retrognathic mandible with backward rotation, prognathic maxilla, and gummy smile. The patient exhibited skeletal Class II malocclusion. Orthodontic miniscrews were placed in the maxillary anterior and posterior segments to provide rigid anchorage and vertical control through intrusion of the incisors and molars. Intrusion and torque control of the maxillary incisors relieved the deep overbite and corrected the gummy smile, while intrusion of the maxillary molars aided in counterclockwise rotation of the mandibular plane, which consequently resulted in an improved facial profile. After 3.5 years of retention, we observed a stable, well-aligned dentition with ideal intercuspation and more harmonious facial contours. Thus, we were able to achieve a satisfactory occlusion, a significantly improved facial profile, and an attractive smile for this patient. The findings from this case suggest that nonsurgical correction using miniscrew anchorage is an effective approach for camouflage treatment of high-angle cases with skeletal Class II malocclusion.

In the adult Chinese population, skeletal Class II malocclusion is often accompanied by a prognathic maxilla and a retrognathic mandible with clockwise rotation, resulting in a convex facial profile, an excessive lower facial height, and compromised facial esthetics.1 Correction of a deep bite accompanied by a gummy smile, very high mandibular plane angle, and retruded chin for the treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion is challenging, particularly in adult patients.2 Skeletal Class II malocclusion with a very high mandibular plane angle is one of the most complex and difficult malocclusions to treat with nonsurgical orthodontic treatment alone, because it is often caused by clockwise rotation of the mandible or excessive vertical growth in the buccal segments.3 The fundamental and most effective treatment method for such a skeletal discrepancy, including the retrognathic mandible, is surgical relocation of the jaw bone.4 However, several patients and their families do not readily accept such invasive surgical methods because of the possible risks and high cost.

An anterior deep bite accompanied by a gummy smile in adults has always been challenging to treat using conventional orthodontic techniques.5 The efficacy of an intrusion utility arch is limited, and the use of this appliance frequently results in undesirable extrusion and flaring of the upper posterior teeth.6 In such cases, surgical therapy involving LeFort impaction may often be required to achieve an attractive smile.7 However, an alternative noninvasive technique for maxillary incisor intrusion should be considered for patients with a severe gummy smile who are not willing to undergo orthognathic surgery.

Recently, the use of orthodontic miniscrews for vertical control has been reported. Molar intrusion of the maxilla using miniscrews facilitates counterclockwise rotation of the mandible, thus correcting a retrusive chin and improving the facial profile.8 In addition, miniscrews are frequently used for maxillary incisor intrusion for the correction of a severe deep overbite accompanied by a gummy smile, and their use has been reported to result in true intrusion.9

The successful use of temporary anchorage devices for providing absolute anchorage during the correction of a deep overbite and gummy smile has been reported.6 However, no report has detailed the simultaneous intrusion of anterior and posterior teeth for the correction of a gummy smile in adults with a very high mandibular plane angle. Here we describe the miniscrew-assisted, nonsurgical correction of a very high mandibular plane angle, retrognathic mandible, and deep overbite accompanied by a gummy smile in a Chinese adult patient with skeletal Class II malocclusion. The treatment plan primarily involved extraction of four premolars with anterior and posterior vertical control and maximum sagittal anchorage to improve the occlusion and facial profile.

A 26-year-old Chinese woman presented with a chief complaint of crooked teeth and a protrusive mouth. She exhibited a gummy smile and could not achieve lip closure at rest. She denied any oral habits, and her medical history showed no contraindications for orthodontic therapy. The patient stated that her facial profile was similar to that of her aunt.

Photographs obtained before treatment showed facial symmetry (Figure 1), although her profile was convex because of a prognathic maxilla and retrognathic mandible, with an increased lower facial height. An acute nasal–labial angle, an incompetent lip, strain in the circumoral musculature on lip closure, and a gummy smile were also observed. Intraoral photographs (Figure 1) and dental casts (Figure 2) revealed an Angle Class II molar relationship with a severe anterior deep bite and moderate crowding of the mandibular teeth. The mandibular midline was shifted to the patient's right by 1 mm. A scissor bite was also observed between the maxillary and mandibular left second molars. The mandibular right second premolar was receiving root canal treatment. The maxillary incisors showed old crown restorations with gingival inflammation (Figure 1).

Lateral cephalometric analysis revealed skeletal Class II malocclusion with a retrognathic mandible (A-point-nasion-B point [ANB], 10.6°) and a high mandibular plane angle (sella-nasion plane to mandibular plane angle [MP/SN], 53.2°). The maxillary incisors were lingually inclined and angled between the crowns and roots because of the presence of post–core restorations (Figure 3).

Panoramic radiographs showed post–core restorations in the maxillary incisors. The mandibular right third molar was mesially impacted, and the root of the mandibular right second premolar was packed with filling materials (Figure 3). There were no signs or symptoms of temporomandibular disorders.

On the basis of the clinical and radiographic findings, the patient was diagnosed with Angle Class II malocclusion with a skeletal Class II base, a very high mandibular plane angle, and a severe deep overbite.

The principal treatment objectives including the following: tooth alignment, achievement of an optimal overjet and overbite, establishment of Class I canine and molar relationships, and correction of the gummy smile and facial profile. The detailed objectives were as follows: alignment and leveling of the dental arch, normalization of the overjet and overbite, intrusion of the maxillary posterior teeth to induce counterclockwise rotation of the mandible and decrease the mandibular plane angle, intrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth to correct the gummy smile, restoration of the mandibular midline, and improvement of the facial profile.

Four treatment alternatives were considered for this patient. The first was orthodontic treatment in combination with orthognathic surgery involving Le Fort I osteotomy for maxillary impaction and bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy for mandibular rotation. This strategy could fundamentally resolve the skeletal discrepancy. The second was fixed-appliance orthodontic treatment complemented by genioplasty, which could correct the retrusive chin. The third was conventional orthodontic treatment with extraction and Class II elastics to achieve a compromised result without skeletal correction. The fourth was a miniscrew-assisted fixed-appliance approach with extraction of four premolars and third molars to retract the maxillary arch and control the anterior and posterior vertical dimensions in an attempt to decrease the mandibular plane angle and relive the deep overbite. The first and second options were ruled out because the patient was reluctant to undergo surgery. The third option was rejected because the patient had high expectations with regard to her facial esthetics. The fourth option was fully explained to the patient, and she was willing to co-operate over the course of the entire orthodontic treatment, including miniscrew insertion.

After obtaining approval from the ethics committee of Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, China and written consent from the patient, the final treatment plan was initiated in September 2009. Under local anesthesia, the maxillary right and left first premolars, mandibular right and left second premolars, and the maxillary and mandibular right third molars were extracted. A preadjusted edgewise appliance with 0.022-inch slots (TP Orthodontics, La Porte, IN, USA) was bonded on both arches (Figure 4).

Alignment and leveling with sequential nickel-titanium archwires, beginning with 0.014-inch wires and ending with 0.019 × 0.025-inch wires, were achieved in 6 months. Under local infiltration anesthesia, miniscrews (diameter, 1.5 mm; length, 8 mm; Zhongbang Medical Treatment Appliance, Xi'an, China) were inserted into the buccal and palatal alveolar bone in the maxillary posterior region on both sides. An elastic tieback with a single power-chain unit was tied from the maxillary left palatal miniscrew to the maxillary left second molar for correction of the scissor bite between the maxillary and mandibular left second molars and for avoiding mesial movement of the maxillary left first molar (Figures 4 and 5A). The force used to correct the scissor bite was 50 gN, and the bite was corrected after two appointments. The bilateral maxillary molars were intruded using elastic chains extending from the miniscrews to the buccal tubes, with a force of approximately 50 gN on each side (Figure 5B and 5C).

A classic sliding mechanism with a 0.019 × 0.025-inch stainless steel archwire was used for space closure in both arches. All the tiebacks were placed on the miniscrews to avoid mesial movement of the molars (Figure 4B). Under local anesthesia, miniscrews (diameter, 1.5 mm; length, 7 mm) were inserted into the maxillary anterior alveolar bone on both sides for incisor intrusion, with a force of approximately 50 gN per side (Figures 4B and 5D). An intrusion force was applied to the central and lateral incisors to relieve the deep overbite and correct the gummy smile. Long-distance elastics were not used for space closure and retraction to avoid molar extrusion. A helical spring was used to reserve space for maxillary incisor crown or veneer placement at 19 months after bonding, in the finishing and detailing stage, when an obvious improvement in her gummy smile was observed (Figures 6 and 5F). A short vertical elastic was used to increase intercuspation and co-ordinate the maxillary and mandibular midlines. The overall duration of active treatment was 25 months. At the end of active treatment, the miniscrews were removed after debonding and space was reserved for the maxillary and mandibular central and lateral incisors (Figure 7). Then, the maxillary central incisors were restored with post crowns, while the lateral incisors were restored with veneers. Subsequently, full-mouth records were obtained to assess the treatment outcomes (Figure 8). Vacuum-formed retainers for full-time wear were provided.

An obviously improved, harmonious facial profile, a charming smile, and a well-aligned dentition were achieved. The scissor bite and deep overbite were corrected, and Class I molar and canine relationships were established. The chin deficiency was corrected and the lower facial height was decreased, resulting in an obviously improved facial profile (Figure 8). Her gummy smile showed a dramatic improvement. An ideal overjet and overbite were achieved. Both intercuspation from the buccal view and occlusion from the lingual view were ideal (Figure 9). Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible, intrusion of the maxillary molars and incisors, a decrease in the mandibular plane angle, and retraction of the maxillary and mandibular incisors were observed. Evidence of these changes was further provided by cephalometric analysis; the MP/SN decreased by 3.3°, the sella-nasion-B (SNB) point angle increased by 2.8°, the ANB angle decreased by 3.2°, and U1/L1 decreased by 14.4° (Figures 10 and 11, Table 1). A panoramic radiograph showed acceptable root parallelism and no obvious apical root resorption, except some root resorption in the maxillary incisors (Figure 10).

The patient was satisfied with the treatment outcomes. At the 3.5-year follow-up visit, she exhibited stable intercuspation, a harmonious facial profile, and an attractive smile (Figure 12).

In the present case, we applied the most commonly used straight-wire technique, which is based on sliding mechanics, assisted by miniscrew anchorage for the correction of a severe deep overbite accompanied by a gummy smile in an adult patient with a very high mandibular plane angle. The combination of posterior and anterior vertical control and sagittal skeletal anchorage simplified the orthodontic treatment procedure, minimized the need for patient compliance, and improved the outcomes of camouflage orthodontic treatment.10

Anchorage control in fixed orthodontic treatment is one of the most important factors influencing the treatment plan and outcomes, particularly in adult high-angle cases.11 Our patient was an adult female who presented with a chief complaint of a protrusive mouth, crooked teeth, and a gummy smile, factors that had significantly affected her ordinary life and social communication. Her pretreatment profile showed severe maxillary prognathism and mandibular retrognathism. Therefore, maximum anteroposterior anchorage was considered necessary. The maxillary incisors were considerably retracted to improve the convex facial profile and gummy smile using miniscrews. The crown-root ratio for the central incisors was almost 1:1 before treatment and more than 1:1 after treatment. Apical root resorption in the maxillary incisors can occur as a result of intrusion and long-distance retraction using miniscrews. Although root resorption occurred in the maxillary incisors after treatment, the overall condition of these teeth was acceptable. Moreover, a stable, well-aligned dentition with ideal intercuspation and harmonious facial contours was observed at the 3.5-year follow-up visit, indicating that the maxillary incisors had remained stable. The patient also exhibited a 100% anterior deep bite before treatment. Stainless steel wires with a reverse curve of Spee are often used to correct a deep overbite in the conventional straight-wire technique based on sliding mechanics. The mechanism of treatment involves intrusion of the mandibular anterior teeth and extrusion of the premolars and upright molars. However, extrusion of the premolars and molars in high-angle cases with mandibular retrognathism is detrimental to the facial profile and chin projection. Molar intrusion is necessary to correct a high mandibular plane angle and counteract the side effects of deep bite correction.12 We previously reported that maxillary molar intrusion using miniscrews in the maxillary posterior segment was effective in controlling vertical dimensions in high-angle cases.13 For maxillary molar intrusion without buccal tipping, we inserted miniscrews in both the maxillary buccal and palatal segments in the present case.

Vertical control in the maxillary posterior segment is beneficial for the correction of a high angle; however, it can increase the overbite, which is undesirable in patients with a deep overbite. Our patient also exhibited a severe gummy smile. The causes of this excess gingival visibility were multifactorial, including vertical overgrowth of the anterior maxilla, incompetent labial muscles, and a prognathic maxilla.1214 Although orthognathic surgery is the best choice of treatment for a severe gummy smile resulting from anterior vertical maxillary overgrowth, miniscrew anchorage can be used as an alternative method to treat patients who refuse orthognathic surgery.15 We chose maximum anchorage for sagittal retraction and intruded the maxillary incisors with light force using the miniscrews for remodeling of the maxillary anterior alveolar bone. We believed that both maxillary incisor intrusion and maxillary labial muscle relaxation after maxillary retraction contributed to correction of the gummy smile. Moreover, maxillary incisor intrusion contributed to a decrease in the overbite. There is another benefit of miniscrew-assisted maxillary incisor intrusion. The inclination of the maxillary central incisors was not satisfactory in our patient. The pretreatment upper incisor to sella-nasion plane (U1-SN) angle was only 95°, probably because of a compensatory mechanism for the skeletal Class II jaw relationship and the angulated post crown restorations. This incisor retroclination increased the difficulty in retracting the maxillary anterior teeth. A labial crown torque was added to the stainless steel wire during space closure. Tooth proclination, the so-called side effect of maxillary incisor intrusion using miniscrews, can thus benefit correction of the incisor inclination. Above all, the combination of anterior and posterior vertical control effectively facilitated correction of both the high mandibular plane angle and the deep overbite with the gummy smile.14

Extraction treatment with conventional orthodontic mechanics is not always effective in controlling the vertical dimension, despite molar mesialization.16171819 It remains unclear whether non-extraction or a different extraction pattern affects the occlusal wedge. A study has reported large linear vertical dimensions in both extraction and nonextraction cases, with greater changes in the vertical dimension in extraction cases.19 A retrospective study analyzed the effects of extraction combined with high-pull headgear extraction and compared them with the effects of nonextraction treatment without vertical control for high-angle cases with similar hyperdivergent skeletal patterns, malocclusion patterns, skeletal ages, and sex distribution.20 The study demonstrated the limitations of conventional orthodontics with regard to significant alterations in skeletal vertical dimensions.20 Therefore, vertical control is crucial in the orthodontic treatment of high-angle cases, particularly adult patients with no further growth potential, such as ours, who exhibited a 49° mandibular plane angle and an increased lower facial height. Miniscrew-assisted molar intrusion in this high-angle case provided a force system that effectively controlled her posterior dentoalveolar dimensions and significantly improved her chin projection and overall facial profile.21 Compared with high-pull headgear treatment, J-hook treatment, the multiloop edgewise archwire technique, and other techniques for vertical control, our miniscrew-assisted technique significantly simplified the entire force system, minimized any difficulty in wire bending, and maintained an appropriate labial inclination for the maxillary incisors. Moreover, this technique was not very dependent on patient compliance.22 Comparison of her pretreatment and post-treatment records showed satisfactory outcomes that could rival those of orthognathic surgery.

As mentioned above, a gummy smile is a multifactorial esthetic problem resulting from maxillary anterior vertical overgrowth, incompetent labial muscles, and other intraoral or extraoral etiologies.121415 Correction of the anterior deep bite in our patient was difficult, considering the possibility of further deepening caused by sagittal retraction of the anterior teeth and intrusion of the posterior teeth. Intrusion of the anterior teeth using miniscrews effectively improved the gummy smile with simultaneous control of the overbite.1523

A scissor bite is a common posterior transverse discrepancy24 that can be caused by buccal inclination of the maxillary molars, lingual inclination of the mandibular molars, a combination of both, or a width discrepancy in the basal bone.11 Interactive elastics are most commonly used to correct a scissor bite caused by abnormal inclination of the molars. However, interarch elastics can also cause molar extrusion, subsequently increasing the mandibular plane angle and rotating the mandible clockwise.25 All these factors can further worsen the facial profile. The main reason for the scissor bite in our patient was the buccal inclination of the maxillary left second molar. Accordingly, we used the maxillary palatal miniscrew for simultaneous lingual movement and intrusion of this tooth.2426 To avoid occlusal interference, we placed glass ionomer cement on the occlusal surfaces of the mandibular first molars to temporarily elevate the occlusion. We thus corrected the scissor bite using light force in only 2 months.

We agree that the decrease in the mandibular plane angle was not sufficient and that the post-treatment lower facial height was still unsatisfactory. However, the pretreatment mandibular plane angle was too high and could not be decreased dramatically, despite the progress in vertical control. Furthermore, the mandibular first molars were extruded a little during mesial movement and leveling of the mandibular arch. The use of additional miniscrews in the mandibular arch, including the buccal shelf area, may avoid molar extrusion. Another problem that needed attention was the consequent root resorption after maxillary incisor intrusion and long-distance retraction. For adult patients requiring vertical control, the intrusion force should be strictly maintained to minimize the degree of root resorption.

We showed that camouflage orthodontic procedures assisted by vertical control via miniscrews required less compliance and were highly successful in treating a very high mandibular plane angle with mandibular retrognathism, deep overbite, and gummy smile in an adult patient who was reluctant to undergo orthognathic surgery. The technique involved intrusion of both the anterior and posterior maxillary segments, favorable counterclockwise rotation of the mandible, restoration of the ideal overjet and overbite, and a decrease in the excess anterior gingival visibility. Stable outcomes were observed at 3.5 years after treatment, although longer follow-up is necessary to assess the long-term stability of treatment. This case report showed the importance of vertical control in camouflage orthodontic treatment for adult high-angle case. Miniscrews were simple and effective in facilitating intrusion of both the upper anterior and posterior teeth, resulting in precise vertical control.

Figures and Tables

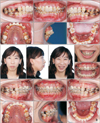

Figure 1

Pretreatment facial photographs show mouth protrusion, retrognathic mandible, increased lower facial height, gummy smile and incompetent lips. Pretreatment intraoral photographs show an Angle Class II molar relationship, a severe anterior deep bite, moderate crowding of the lower arch, shifted lower midline, and old crown restorations with gingival inflammation in the maxillary incisors.

Figure 2

Pretreatment dental casts. An Angle Class II molar relationship, anterior deep bite (100%), moderate crowding of the lower arch and a posterior scissor bite between the maxillary and mandibular left second molars can be observed.

Figure 3

Pretreatment cephalogram (A), cephalometric tracing (B), and panoramic radiograph (C). Pretreatment cephalogram shows a skeletal Class II malocclusion with a retrognathic mandible and a very high mandibular plane angle. The maxillary incisors are lingually inclined and angled between the crowns and roots because of the angulated post-core crowns. Pretreatment panoramic radiographs show post-core restorations in the maxillary incisors, mesially impacted lower right third molar, and the root of the lower right second premolar is packed with filling materials.

Figure 4

Detailed treatment progression. A, Three months after bonding. Fixed appliances applied with 0.016-inch nickel-titanium archwires. The maxillary left palatal miniscrew is used for intrusion and lingual movement of the maxillary left second molar. B, Seven months after bonding. Severe gummy smile can be observed on full smile. Conventional sliding mechanics using 0.019 × 0.025-inch stainless steel archwire is used for space closure in both arches, with tiebacks to the miniscrews. The miniscrews are used to intrude the maxillary molars and anterior teeth. Class II intermaxillary elastics are used for a short time for mesial movement of the mandibular molars and correction of the molar relationship.

Figure 5

A, Correction of scissor bite using the maxillary left palatal miniscrew. An elastic tieback with a single power-chain unit is tied from the miniscrew to the maxillary left second molar. B, The maxillary molars are intruded using elastic tiebacks connected to the palatal miniscrews (approximately 50 gN). C, The maxillary molars are intruded using elastic tiebacks connected to the buccal miniscrews (approximately 50 gN). The space in both arches is closed using the elastic tiebacks (approximately 180 gN). D, The maxillary incisors are intruded using miniscrews with a light force (approximately 50 gN). E, At 7 months after bonding, a severe gummy smile can be observed. F, At 19 months after bonding, the gingival visibility has evidently decreased.

Figure 6

Facial and extraoral photographs obtained at 19 months after bonding. The gingival visibility has evidently decreased. A helical spring is used to reserve space for crowns or veneers on the maxillary incisors.

Figure 7

Post-treatment facial and intraoral photographs. The facial profile has been improved, ideal intercuspation with Class I molar and canine relationships are achieved; the overjet and overbite have been decreased, with space reservation for further restoration of the maxillary incisors.

Figure 8

Facial and intraoral photographs obtained after final restorations. The post-treatment facial photographs show the facial esthetics has been obviously improved with the chin deficiency corrected and the lower facial height decreased. The gummy smile is dramatically improved. The post-treatment intraoral photographs show Class I molar and canine relationships with normalized overjet and overbite.

Figure 9

Post-treatment dental casts. The dentition is well aligned, the scissor bite and deep overbite are corrected, and ideal intercuspation with solid lingual occlusion is achieved.

Figure 10

Post-treatment cephalogram, cephalometrict racing, and panoramic radiograph. The post-treatment cephalogram shows decreased mandibular plane angle and A-point-nasion-B point angle. The post-treatment panoramic radiograph shows acceptable root parallelism and no obvious apical root resorption.

Figure 11

Pre- and post-treatment cephalometric superimpositions showing marked differences before (blue) and after (red) treatment. A, Overall superimposition at sella-nasion plane. Convex profile is improved and contour-clockwise rotation of the mandible is observed. B, Maxillary superimposition at palatal plane (anterior nasal spine to posterior nasal spine). Retraction and intrusion of the upper incisors and intrusion of the upper molars are observed. C, Mandibular superimposition at mandibular plane (menton to gonion). Intrusion of the lower incisors and mesially movement of the lower molars are observed.

Figure 12

Facial and intraoral photographs obtained at 3.5 years after treatment. Stable occlusion and a satisfactory facial profile can be observed. A harmonious facial profile, an attractive smile, Class I molar and canine relationships and stable intercuspation are maintained.

Table 1

Skeletal and dental changes indicated by cephalometric measurements

SNA, Sella-nasion-A point; SNB, sella-nasion-B point; ANB, A point-nasion-B point; U1/NA, upper incisor to nasion-A point line; L1/NB, lower incisor to nasion-B point line; U1/L1, interincisal angle; U1/SN, upper incisor to sella-nasion plane; MP/SN, mandibular plane to sella-nasion plane; MP/FH, mandibular plane to Frankfort Horizontal plane; L1/MP, lower incisor to mandibular plane; Z angle, FH plane to profile line (pogonion to lip contact line); U6-MxP, upper first molar to maxillary plane; L6-MnP, lower first molar to mandibular plane; SD, standard deviation.

References

1. Canavarro C, Zanella E, Medeiros PJ, Capelli J Jr. Surgical-orthodontic treatment of Class II malocclusion with maxillary vertical excess. J Clin Orthod. 2009; 43:387–392.

2. Shu R, Huang L, Bai D. Adult Class II Division 1 patient with severe gummy smile treated with temporary anchorage devices. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011; 140:97–105.

3. Abraham J, Bagchi P, Gupta S, Gupta H, Autar R. Combined orthodontic and surgical correction of adult skeletal class II with hyperdivergent jaws. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 3:65–69.

4. Bell WH, Jacobs JD, Legan HL. Treatment of Class II deep bite by orthodontic and surgical means. Am J Orthod. 1984; 85:1–20.

5. Fowler P. Orthodontics and orthognathic surgery in the combined treatment of an excessively "gummy smile". N Z Dent J. 1999; 95:53–54.

6. Nishimura M, Sannohe M, Nagasaka H, Igarashi K, Sugawara J. Nonextraction treatment with temporary skeletal anchorage devices to correct a Class II Division 2 malocclusion with excessive gingival display. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014; 145:85–94.

7. Shimo T, Nishiyama A, Jinno T, Sasaki A. Severe gummy smile with class II malocclusion treated with LeFort I osteotomy combined with horseshoe osteotomy and intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy. Acta Med Okayama. 2013; 67:55–60.

8. Upadhyay M, Yadav S, Nanda R. Vertical-dimension control during en-masse retraction with mini-implant anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010; 138:96–108.

9. Hong RK, Lim SM, Heo JM, Baek SH. Orthodontic treatment of gummy smile by maxillary total intrusion with a midpalatal absolute anchorage system. Korean J Orthod. 2013; 43:147–158.

10. Cacciafesta V, Bumann A, Cho HJ, Graham JW, Paquette DE, Park DE, et al. Skeletal anchorage, part 1. J Clin Orthod. 2009; 43:303–317.

11. Jung MH. Treatment of severe scissor bite in a middle-aged adult patient with orthodontic mini-implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011; 139:4 Suppl. S154–S165.

12. Lin JC, Liou EJ, Bowman SJ. Simultaneous reduction in vertical dimension and gummy smile using miniscrew anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 2010; 44:157–170.

13. Ouyang L, Zhou YH, Fu MK, Ding P. Extraction treatment of an adult patient with severe bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion using microscrew anchorage. Chin Med J (Engl). 2007; 120:1732–1736.

14. Redlich M, Mazor Z, Brezniak N. Severe high Angle Class II Division 1 malocclusion with vertical maxillary excess and gummy smile: a case report. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999; 116:317–320.

15. Kaku M, Kojima S, Sumi H, Koseki H, Abedini S, Motokawa H, et al. Gummy smile and facial profile correction using miniscrew anchorage. Angle Orthod. 2012; 82:170–177.

16. Hans MG, Groisser G, Damon C, Amberman D, Nelson S, Palomo JM. Cephalometric changes in overbite and vertical facial height after removal of 4 first molars or first premolars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 130:183–188.

17. Wang Y, Yu H, Jiang C, Li J, An S, Chen Q, et al. Vertical changes in Class I malocclusion between 2 different extraction patterns. Saudi Med J. 2013; 34:302–306.

18. Aras A. Vertical changes following orthodontic extraction treatment in skeletal open bite subjects. Eur J Orthod. 2002; 24:407–416.

19. Sivakumar A, Valiathan A. Cephalometric assessment of dentofacial vertical changes in Class I subjects treated with and without extraction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008; 133:869–875.

20. Gkantidis N, Halazonetis DJ, Alexandropoulos E, Haralabakis NB. Treatment strategies for patients with hyperdivergent Class II Division 1 malocclusion: is vertical dimension affected? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011; 140:346–355.

21. Hart TR, Cousley RR, Fishman LS, Tallents RH. Dentoskeletal changes following mini-implant molar intrusion in anterior open bite patients. Angle Orthod. 2015; 85:941–948.

22. Kim TW, Kim H, Lee SJ. Correction of deep overbite and gummy smile by using a mini-implant with a segmented wire in a growing class II division 2 patient. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 130:676–685.

23. Polat-Ozsoy O, Arman-Ozcirpici A, Veziroglu F. Miniscrews for upper incisor intrusion. Eur J Orthod. 2009; 31:412–416.

24. Kalia A, Sharif K. Scissor-bite correction using miniscrew anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 2012; 46:573–579. quiz 583.

25. Wilson GB, Kidner G, Hemmings K. The use of implants at an increased vertical dimension of occlusion to correct a scissor bite: a case report. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2008; 16:67–72.

26. Alani A, Bishop K, Knox J, Gravenor C. The use of implants for anchorage in the correction of unilateral crossbites. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2010; 18:123–127.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download