Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to investigate the characteristics of orthodontic patients at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 to 2012.

Methods

We evaluated Angle's classification from molar relationships, classification of skeletal malocclusion from the A point-nasion-B point angle, facial asymmetry, and temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs) from the records of 7,476 patients who received an orthodontic diagnosis. The orthognathic surgery rate, extraction rate, and extraction sites were determined from the records of 4,861 treated patients.

Results

The patient number increased until 2010 and gradually decreased thereafter. Most patients were aged 19−39 years, with a gradual increase in patients aged ≥ 40 years. Angle's Class I, Class II divisions 1 and 2, and Class III malocclusions were observed in 27.7%, 25.6%, 10.6%, and 36.1% patients, respectively, with a gradual decrease in the frequency of Class I malocclusion. The proportion of patients with skeletal Class I, Class II, and Class III malocclusions was 34.3%, 34.3%, and 31.4%, respectively, while the prevalence of facial asymmetry and TMDs was 11.0% and 24.9%, respectively. The orthognathic surgery rate was 18.5%, with 70% surgical patients exhibiting skeletal Class III malocclusion. The overall extraction rate among nonsurgical patients was 35.4%, and the maxillary and mandibular first premolars were the most commonly extracted teeth.

Conclusions

The most noticeable changes over time included a decrease in the patient number after 2010, an increase in the average patient age, and a decrease in the frequency of Angle's Class I malocclusion. Our results suggest that periodic characterization is necessary to meet the changing demands of orthodontic patients.

Epidemiology is defined as the study of the patterns, causes, and effects of health and disease conditions in defined populations.1 Dental epidemiology provides information on normal biological processes and diseases of the oral and maxillofacial regions, and it aids in the establishment of oral health policies and evidence-based practice, education of professionals, and comparison of information among different populations or within a single population at different time points.

The demand for orthodontic treatment changes with changing trends in esthetic demands, socioeconomic factors, and social recognition of orthodontic treatment.23 Recently, the distribution of knowledge through the internet and mass media, an increase in the number of dental professionals, and rapid advances in orthodontic techniques have been accelerating this trend. Therefore, periodic epidemiologic studies on the classification and distribution of orthodontic patients are warranted to accommodate these continuously changing orthodontic demands.

Epidemiologic studies may be performed to analyze the general population or groups of orthodontic patients. Data for the general population differ significantly from data for orthodontic patient populations because of different orthodontic needs. Moreover, epidemiologic data are applicable only when they are derived from the same population of orthodontic patients, because epidemiologic factors differ among racial and ethnic groups. Several studies on Korean orthodontic patient populations have been conducted;45678910111213141516 however, the last study of a large population was published in 2009,16 and those data require to be updated as per the current trends. Investigation of changing trends in orthodontic demands by a comparison of new data with those obtained from previous studies is also worthwhile.

From the above perspectives, we conducted this study to investigate the classification and distribution of orthodontic patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital over a 5-year period (2008–2012).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei Dental Hospital (2-2015-0022). We audited all records of 15,551 patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 to 2012. Of these, 7,476 patients who received an orthodontic diagnosis and for whom high-quality panoramic radiographs and lateral cephalograms were available were included in this study, regardless of whether they received orthodontic treatment. Frontal cephalograms were obtained for 3,798 patients because of facial asymmetry noted during clinical examination. Figure 1 shows a flowchart depicting the process of patient inclusion.

The following information that was not related to treatment was collected from the patients' records, diagnostic casts, and lateral and frontal cephalograms: sex; age; Angle's classification obtained from diagnostic casts; the A point-nasion-B point (ANB) angle obtained from lateral cephalograms; the presence of facial asymmetry, defined as a menton deviation of > 4 mm on frontal cephalograms;17 and the presence of temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs), defined as the presence of pain, limited mouth opening, and/or an audible sound heard on joint movement.18 Treatment-related information, including details of extractions in patients who did not undergo surgical procedures and details of orthognathic surgeries, was obtained from the records of 4,861 patients for whom orthodontic treatment was initiated.

The patients were divided into subgroups according to their age, ANB angle, and extraction site. A total of five age groups were defined as follows: Group 1, including patients aged < 7 years (primary dentition); Group 2, aged 7−12 years (mixed dentition); Group 3, aged 13−18 years (permanent dentition); Group 4, aged 19−39 years (young adults); and Group 5, aged ≥ 40 years (middle-aged adults). The degree of skeletal malocclusion was classified into three groups as follows: skeletal Class I (ANB angle within the mean ± 1 standard deviation [SD] for an age-matched population), skeletal Class II (ANB angle higher than the mean + 1 SD for an age-matched population), and skeletal Class III (ANB angle smaller than the mean − 1 SD for an age-matched population).19 Patients who did not undergo surgical procedures were divided into six groups on the basis of their extraction sites: Group A, maxillary and mandibular first premolars; Group B (four premolars other than the first four); Group C, maxillary premolars; Group D, mandibular premolars; Group E, maxillary second molars; and Group F, teeth other than those extracted in Groups A to E. Extraction of the third molar was considered a nonextraction treatment, regardless of the purpose of extraction.

Chi-square tests were performed to analyze any interactions between the following factors: (1) year (2008 to 2012) versus sex, age, Angle's classification, and the degree of skeletal malocclusion with regard to the frequency of patients; (2) age versus the degree of skeletal malocclusion with regard to the frequency of TMDs; (3) year (2008 to 2012) versus the degree of skeletal malocclusion with regard to the frequency of orthognathic surgery and extraction; and (4) extraction site versus the degree of skeletal malocclusion with regard to the frequency of patients. Linear-by-linear associations were calculated to detect any linear relationships between groups. In addition, chi-square tests were used to investigate the homogeneity of the following variables: (1) frequency of patients from 2008 through 2012 in the different age groups (Groups 1 to 5), Angle's classification groups, and skeletal malocclusion groups; (2) proportion of patients with facial asymmetry in the skeletal malocclusion groups; (3) frequency of TMDs in the different age groups and skeletal malocclusion groups; (4) surgery and extraction rates from 2008 through 2012 and in the skeletal malocclusion groups; and (5) frequency of patients in the six extraction site groups (Groups A to F). Statistical analyses were performed at a 5% significance level using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

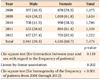

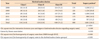

The number of visiting patients fluctuated significantly during the investigation period (p < 0.001), increasing from 2008 to 2010 and decreasing thereafter. The proportion of male and female patients was approximately 40% and 60%, respectively, showing slight changes from 2008 through 2012 (p > 0.05; Table 1).

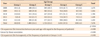

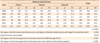

With regard to age, Group 4 comprised the maximum patients (47.5%), followed by Group 2 (24.1%) and Group 3 (23.1%; p < 0.001). Interestingly, the number of middle-aged patients (Group 5) gradually increased with time, while the proportion of children and adolescents (Groups 1 to 3) gradually decreased. Chi-square tests revealed a significant change in the distribution of patients in the different age groups (p < 0.001), and there was a significant linear trend in this change from 2008 through 2012 (p < 0.001; Table 2).

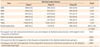

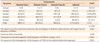

With regard to the types of malocclusion, statistically significant changes in the frequency of patients (p = 0.014) and linear trends (p = 0.001) were observed in Angle's classification (Table 3), but not in skeletal malocclusion classification (p > 0.05; Table 4). The proportion of patients with Angle's Class I malocclusion was lower (27.7%) than that of patients with Angle's Class II (division 1 and 2) and Class III malocclusions (36.2% and 36.1%, respectively); these values gradually decreased from 2008 through 2012 (Table 3). With regard to skeletal malocclusion, similar numbers of patients exhibited Class I and Class II, with skeletal Class III being the least frequent (31.4%; p = 0.002). The prevalence of facial asymmetry differed among the different degrees of skeletal malocclusion (p < 0.001), being the highest in patients with skeletal Class III malocclusion, followed by those with skeletal Class I and Class II malocclusions (Table 4).

The prevalence of TMDs was calculated for 7,116 patients who received clinical examinations for the same. The prevalence differed among the five age groups (p < 0.001) and skeletal malocclusion groups (p < 0.001). A gradual increase was noted from Groups 1 to 4, with the highest prevalence in young adults (37.4%) and a decrease in Group 5. Patients with Class II skeletal malocclusion showed the highest prevalence of TMDs (Table 5).

Among the 7,476 patients who received an orthodontic diagnosis, orthodontic treatment was initiated for 4,861. The total proportion of patients who received orthognathic surgery was 18.5%, with an increase from 2008 to 2009 and a decrease from 2009 through 2012 (p < 0.001). Approximately 70% surgical patients exhibited skeletal Class III malocclusion (Table 6). For nonsurgical patients, the average overall extraction rate was 35.4%; this rate increased from 2008 to 2010 and decreased thereafter (p < 0.001). The extraction rate differed according to skeletal malocclusion classification (p < 0.001), being the highest in patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion (47.6%), followed by those with skeletal Class I (33.5%) and Class III (16.0%) malocclusions (Table 7). The extraction site also differed among the skeletal malocclusion groups (p < 0.001), with the maxillary and mandibular first premolars being the most commonly extracted teeth in all skeletal malocclusion groups. The second most commonly extracted teeth were the maxillary and mandibular second premolars in patients with skeletal Class I and Class III malocclusions and the maxillary premolars in patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion. The proportion of patients who underwent mandibular premolar extractions was higher in the skeletal Class III group than in the other two skeletal malocclusion groups (Table 8).

The characteristics of orthodontic patients gradually change over time, warranting periodic epidemiologic studies. In this study, we investigated the classification and distribution of orthodontic patients who visited Yonsei Dental Hospital over a 5-year period from 2008 through 2012, providing sufficient data for comparison with previously published data.

The annual number of patients visiting the study hospital gradually increased from 2008 to 2010 and decreased thereafter. This finding is in contrast to that of previous studies that showed a continuous increase in the number of patients over time.4681011121315 The decrease in patient numbers from 2010 through 2012 was probably due to the redistribution of orthodontic patients to local clinics, considering the recent increase in the number of orthodontic specialists and general dentists treating orthodontic patients, rather than a decrease in orthodontic treatment demand.

The number of female patients was approximately 1.5 times the number of male patients in the present study. This ratio is similar to those reported in previous studies (1.4–1.9:1),461011121315 indicating that women are more interested in esthetics compared with men and consequently seek orthodontic treatment more frequently. This sex difference was more apparent in patients over 18 years of age, a group with a female:male ratio of 1.8:1 (data not shown).

While the number of adult patients (Groups 4 and 5) gradually increased over time, the number of children and adolescents (Groups 1 to 3) gradually decreased. The number of patients in Group 5 nearly doubled from 2008 through 2012. These results are in accordance with those of previous studies121416 and are partly due to the aging of the population. However, the increasing age of orthodontic patients far outpaced the age of the general population; this may be attributed to changes in public opinions regarding orthodontic treatment for older patients, the recent introduction of esthetic appliances, and advances in orthodontic techniques that may decrease discomfort and adverse effects during treatment.

With regard to Angle's classification, the proportion of patients with Class I malocclusion gradually decreased during the investigation period. Yu et al.12 reported that the proportion of patients with Class I malocclusion was 33.3% in 1999, indicating a gradual decrease over time. One possible explanation for this finding is that patients with Class I malocclusion, which is considered relatively easy to treat, were treated at local clinics instead of the hospital. Our results were slightly different when skeletal malocclusion was considered, probably because only the ANB angle was used to classify the degree of skeletal malocclusion or because of the discrepancy between the sagittal skeletal relationship and occlusion.

In this study, facial asymmetry was observed in 11.0% patients, which was comparable with the values reported in previous studies where the prevalence of facial asymmetry in orthodontic patient populations ranged from 4.0−23%.101420 This was probably because of different definitions of facial asymmetry in different studies. One consistent finding is that facial asymmetry is most frequently found in patients with skeletal Class III malocclusion,17202122 as observed in the present study. The reason for this finding may be that asymmetric mandibular growth occurs more readily in patients with mandibular prognathism.22

TMDs were observed in approximately one-fourth of the patients in our study; this was higher than the 4.6% reported by Baik et al.10 This difference is caused by different definitions of TMDs. In our study, TMDs were defined as the presence of one or more of the following symptoms: pain, limited mouth opening, and the presence of a sound on joint movement. Baik et al.10 defined TMDs as the presence of two or more of these symptoms. In our study, the prevalence of TMDs gradually increased up to middle age, following which it decreased. These findings indicate that TMD is a self-limiting disease.23

The orthognathic surgery rate in our study was 18.5%, which appeared to be higher than those reported in previous studies.1013151624 This difference results partially from the fact that our surgery rate was calculated using the number of patients who began orthodontic treatment, whereas in some previous studies, the rate was calculated using the total number of patients. Patients with skeletal Class III malocclusion comprised 70% of the total number of surgical patients, indicating that mandibular prognathism is considered socially unacceptable.

The extraction rate in this study was 35.4%. It is difficult to compare this result with those of previous studies because the extraction rate can vary greatly according to the clinician's philosophy, the patient's preference, and social perceptions of an esthetic facial appearance. A more interesting finding was that the extraction rate was the highest for patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion and the lowest for patients with skeletal Class III malocclusion. This was probably because lip protrusion, a major determining factor for extraction, is dependent on protrusion of the nose and chin. Skeletal Class II patients usually exhibit a retruded chin, which accentuates lip protrusion, while skeletal Class III patients exhibited a protruded chin, which decreases lip protrusion. As expected, the maxillary and mandibular first premolars were the most frequently extracted teeth, as expected. Notably, extraction of only the maxillary premolars and mandibular premolars was more frequent in patients with skeletal Class II and Class III malocclusions, respectively.

This study has several limitations. First, only the ANB angle was used to classify the skeletal malocclusion. The ANB angle is one of the most commonly used measurements for the sagittal skeletal relationship; however, it is considerably affected by the sagittal and vertical positions of the nasion.25 Future studies may compensate for this drawback by incorporating other measurements such as the Wits appraisal and the anteroposterior dysplasia indicator. Second, because the study period spanned only 5 years, the study does not reveal long-term trends. Because of this limitation, we focused on comparing the results of this study with those of previous studies. Finally, this study included the records of orthodontic patients at only one dental hospital; therefore, the results may not represent an entire orthodontic patient population. Large-scale studies of patients at multiple clinics should be conducted in the future.

In this study, we analyzed the records of 7,476 orthodontic patients who visited Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 through 2012. The most noticeable changes included a decrease in the number of patients after the year 2010, an increase in the average age of orthodontic patients, and a decrease in the frequency of Angle's Class I malocclusion. These results will aid clinicians in monitoring the changing demands of orthodontic patients.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Patient inclusion flowchart.TMD, Temporomandibular joint disorder.

*Five patients were excluded from the analysis of Angle's classification because of bilaterally missing permanent first molars and/or primary second molars.

|

Table 1

The number of patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 through 2012

Table 2

Age of patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 through 2012

Table 3

Angle's classification for patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 through 2012

Table 4

Skeletal malocclusion and presence of facial asymmetry among patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 through 2012

Table 5

Temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs) in patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 through 2012

Table 6

Orthognathic surgery rate for patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 through 2012

Table 7

Extraction rate for patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 through 2012

Table 8

Extraction sites for patients who visited the Department of Orthodontics at Yonsei Dental Hospital from 2008 through 2012

Values are presented as number (%).

Group A, maxillary and mandibular first premolars; Group B, four premolars other than the first four; Group C, maxillary premolars only; Group D, mandibular premolars only; Group E, maxillary second molars; Group F, teeth other than those extracted in Groups A to E.

References

1. Porta M. A dictionary of epidemiology. 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press;2014.

2. Kazancı F, Aydoğan C, Alkan Ö. Patients' and parents' concerns and decisions about orthodontic treatment. Korean J Orthod. 2016; 46:20–26.

3. Kang JM, Kang KH. Effect of malocclusion or orthodontic treatment on oral health-related quality of life in adults. Korean J Orthod. 2014; 44:304–311.

4. Oh YJ, Ryu YK. A study of types and distribution of patients in the department of orthodontics, infirmary of dental college, Y-university. Korean J Orthod. 1983; 13:63–72.

5. Suhr CH, Nahm DS, Chang YI. Epidemiologic study of the prevalence of malocclusion in Korean. Korean J Orthod. 1984; 14:33–37.

6. Gok DB, Kyung HM, Kwon OW, Sung JH. The distribution and trend of malocclusion patients visited at depatment of orthodontics. Korean J Orthod. 1989; 19:35–48.

7. Kang HK, Ryu YK. A study on the prevalence of malocclusion of Yonsei university students in 1991. Korean J Orthod. 1992; 22:691–701.

8. Yang WS. The study on the orthodontic patients who visited department of orthodontics, Seoul National University Hospital. J Korean Dent Assoc. 1990; 28:811–821.

9. Lee SJ, Kim TW, Suhr CH. Study of recognition of malocclusion and orthodontic treatments. Korean J Orthod. 1994; 24:193–198.

10. Baik HS, Kim KH, Park Y. The distributions and trends in maloclusion patients - A 10 year study of 2155 patients from YDSH. Korean J Orthod. 1995; 25:87–100.

11. Yang W. The study on the orthodontic patients who visited Department of Orthodontics, Seoul National University Hospital during last 10 years (1985–1994). Korean J Orthod. 1995; 25:497–509.

12. Yu HS, Ryu YK, Lee JY. A study on the distributions and trends in malocclusion patients from Department of Orthodontics, College of Dentistry, Yonsei University. Korean J Orthod. 1999; 29:267–276.

13. Hwang MS, Yoon YJ, Kim KW. An epidemiologic study on the orthodontic patients who visited Department of Orthodontics, Chosun University Dental Hospital last 10 years (1990-1999). Korean J Orthod. 2001; 31:283–300.

14. Im DH, Kim TW, Nahm DS, Chang YI. Current trends in orthodontic patients in Seoul National University Dental Hospital. Korean J Orthod. 2003; 33:63–72.

15. Chung SH, Lee HK. Trends in malocclusion patients of Yeungnam University Hospital. Yeungnam Univ J Med. 2006; 23:71–81.

16. Jung MH. Current trends in orthodontic patients in private orthodontic clinics. Korean J Orthod. 2009; 39:36–42.

17. Haraguchi S, Takada K, Yasuda Y. Facial asymmetry in subjects with skeletal Class III deformity. Angle Orthod. 2002; 72:28–35.

18. Helkimo M. Epidemiological surveys of dysfunction of the masticatory system. Oral Sci Rev. 1976; 7:54–69.

19. Baek IS, Ryu YK. Roentgenocephalometric study of craniofacial skeleton on the age of puberty with normal occulsion. Korean J Orthod. 1982; 12:177–192.

20. Willems G, De Bruyne I, Verdonck A, Fieuws S, Carels C. Prevalence of dentofacial characteristics in a belgian orthodontic population. Clin Oral Investig. 2001; 5:220–226.

21. Severt TR, Proffit WR. The prevalence of facial asymmetry in the dentofacial deformities population at the University of North Carolina. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1997; 12:171–176.

22. Chew MT. Spectrum and management of dentofacial deformities in a multiethnic Asian population. Angle Orthod. 2006; 76:806–809.

23. Dworkin SF. Perspectives on the interaction of biological, psychological and social factors in TMD. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994; 125:856–863.

24. Choi Y. The distribution and trend of surgical-orthodontic patients in dental college hospital of Yonsei University [master's thesis]. Seoul: Yonsei University;2012.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download