1. Severt TR, Proffit WR. The prevalence of facial asymmetry in the dentofacial deformities population at the University of North Carolina. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1997; 12:171–176. PMID:

9511487.

2. Samman N, Tong AC, Cheung DL, Tideman H. Analysis of 300 dentofacial deformities in Hong Kong. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1992; 7:181–185. PMID:

1291612.

3. Harila V, Valkama M, Sato K, Tolleson S, Hanis S, Kau CH, et al. Occlusal asymmetries in children with congenital hip dislocation. Eur J Orthod. 2012; 34:307–311. PMID:

21303807.

4. Morel-Verdebout C, Botteron S, Kiliaridis S. Dentofacial characteristics of growing patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a morphological study. Eur J Orthod. 2007; 29:500–507. PMID:

17974540.

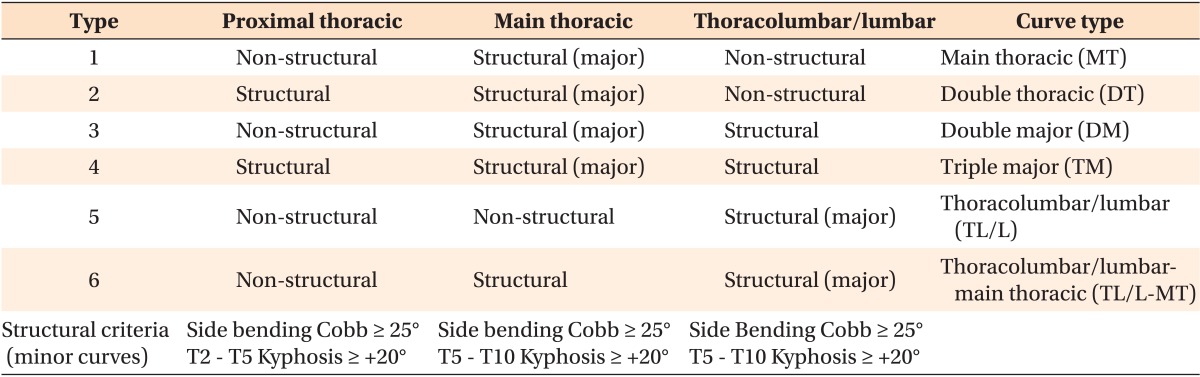

5. Lee CK, Koo KH, An JH. The classification of idiopathic scoliosis. J Korean Soc Spine Surg. 2007; 14:57–66.

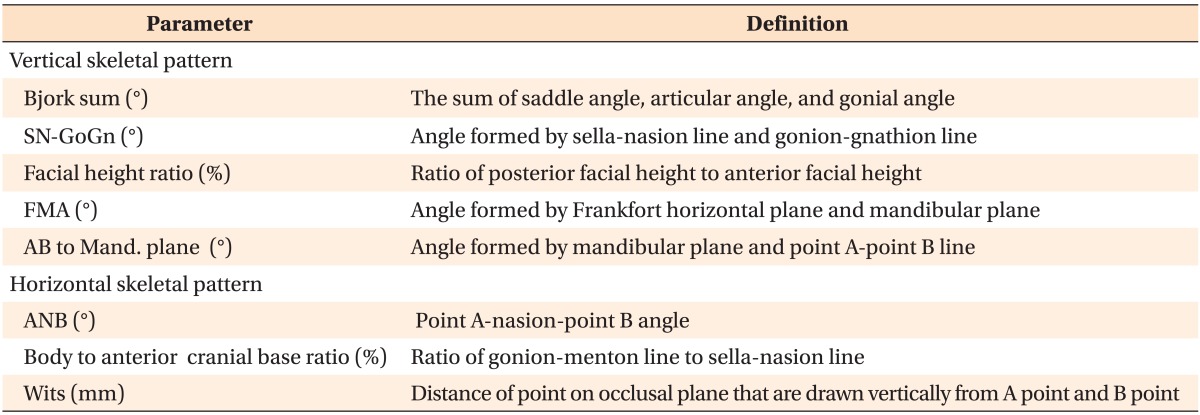

6. Lippold C, Danesh G, Hoppe G, Drerup B, Hackenberg L. Trunk inclination, pelvic tilt and pelvic rotation in relation to the craniofacial morphology in adults. Angle Orthod. 2007; 77:29–35. PMID:

17029550.

7. Pedrotti L, Mora R, Bertani B, Tuvo G, Crivellari I. Association among postural and skull-cervicomandibular disorders in childhood and adolescence. Analysis of 428 subjects. Pediatr Med Chir. 2007; 29:94–98. PMID:

17461096.

8. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, Bridwell KH, Clements DH, Lowe TG, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001; 83-A:1169–1181. PMID:

11507125.

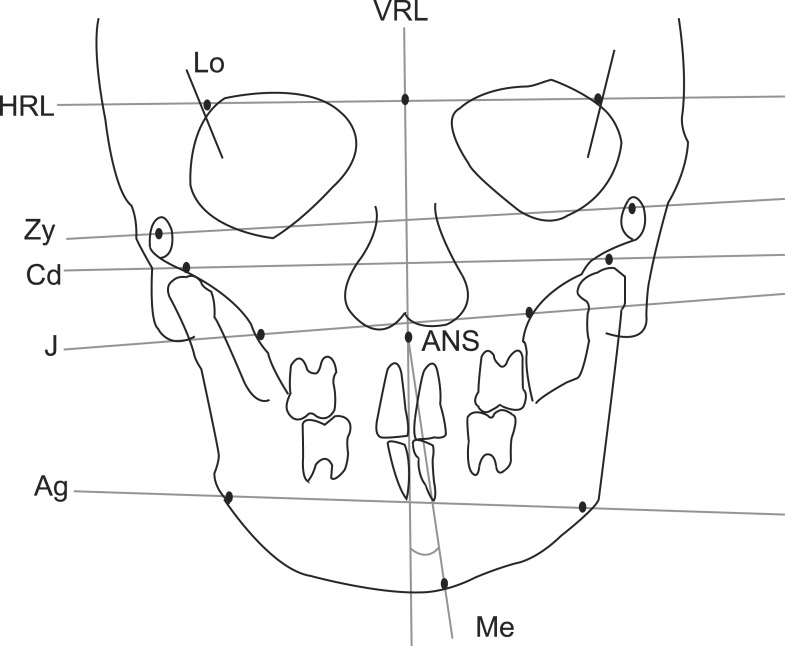

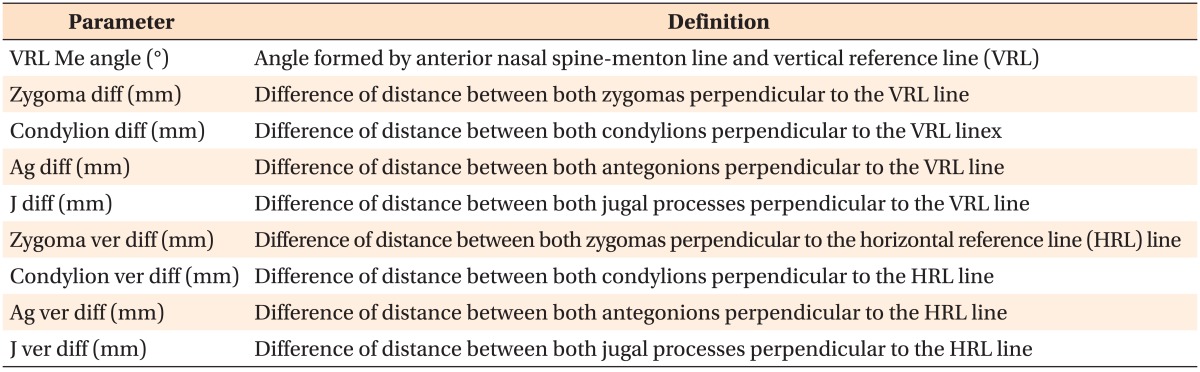

9. Letzer GM, Kronman JH. A posteroanterior cephalometric evaluation of craniofacial asymmetry. Angle Orthod. 1967; 37:205–211. PMID:

19919216.

10. Major PW, Johnson DE, Hesse KL, Glover KE. Landmark identification error in posterior anterior cephalometrics. Angle Orthod. 1994; 64:447–454. PMID:

7864466.

11. Cho JH, Moon JY. Comparison of midsagittal reference plane in PA cephalogram and 3D CT. Korean J Orthod. 2010; 40:6–15.

12. Huggare J. Association between morphology of the first cervical vertebra, head posture, and craniofacial structures. Eur J Orthod. 1991; 13:435–440. PMID:

1817068.

13. Solow B, Sonnesen L. Head posture and malocclusions. Eur J Orthod. 1998; 20:685–693. PMID:

9926635.

14. Ozbek MM, Köklü A. Natural cervical inclination and craniofacial structure. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993; 104:584–591. PMID:

8249934.

15. Houston WJ. Mandibular growth rotations--their mechanisms and importance. Eur J Orthod. 1988; 10:369–373. PMID:

3061834.

16. Solow B, Sandham A. Cranio-cervical posture: a factor in the development and function of the dentofacial structures. Eur J Orthod. 2002; 24:447–456. PMID:

12407940.

17. Motoyoshi M, Shimazaki T, Sugai T, Namura S. Biomechanical influences of head posture on occlusion: an experimental study using finite element analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2002; 24:319–326. PMID:

12198861.

18. Ben-Bassat Y, Yitschaky M, Kaplan L, Brin I. Occlusal patterns in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 130:629–633. PMID:

17110260.

19. Hong JY, Suh SW, Modi HN, Yang JH, Hwang YC, Lee DY, et al. Correlation between facial asymmetry, shoulder imbalance, and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Orthopedics. 2011; 34:187. PMID:

21667906.

20. Saccucci M, Tettamanti L, Mummolo S, Polimeni A, Festa F, Tecco S. Scoliosis and dental occlusion: a review of the literature. Scoliosis. 2011; 6:15. PMID:

21801357.

21. Segatto E, Lippold C, Végh A. Craniofacial features of children with spinal deformities. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008; 9:169. PMID:

19102760.

22. Korbmacher H, Koch L, Eggers-Stroeder G, Kahl-Nieke B. Associations between orthopaedic disturbances and unilateral crossbite in children with asymmetry of the upper cervical spine. Eur J Orthod. 2007; 29:100–104. PMID:

17290022.

23. King HA, Moe JH, Bradford DS, Winter RB. The selection of fusion levels in thoracic idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983; 65:1302–1313. PMID:

6654943.

24. Cummings RJ, Loveless EA, Campbell J, Samelson S, Mazur JM. Interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility of the system of King et al. for the classification of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998; 80:1107–1111. PMID:

9730119.

25. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Bridwell KH, Clements DH, Harms J, Lowe TG, et al. Intraobserver and interobserver reliability of the classification of thoracic adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998; 80:1097–1106. PMID:

9730118.

26. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Haher TR, Lapp MA, Merola AA, Harms J, et al. Multisurgeon assessment of surgical decision-making in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: curve classification, operative approach, and fusion levels. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001; 26:2347–2353. PMID:

11679820.

27. Puno RM, An KC, Puno RL, Jacob A, Chung SS. Treatment recommendations for idiopathic scoliosis: an assessment of the Lenke classification. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003; 28:2102–2114. discussion 2114-5. PMID:

14501921.

28. Suk SI. Introduction of spinal deformity and idiopathic scoliosis. Spinal surgery. 2nd ed. Seoul: Newest Medical Publishing;2004. p. 311–361.

29. Huggare J, Pirttiniemi P, Serlo W. Head posture and dentofacial morphology in subjects treated for scoliosis. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1991; 87:151–158. PMID:

2057482.

30. Lippold C, van den Bos L, Hohoff A, Danesh G, Ehmer U. Interdisciplinary study of orthopedic and orthodontic findings in pre-school infants. J Orofac Orthop. 2003; 64:330–340. PMID:

14692047.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download