INTRODUCTION

Many orthodontists believe that because dental arch length decreases and lower anterior crowding increases throughout life, the only way to maintain ideal alignment after orthodontic treatment is some form of permanent retention.

1-

6 Fixed bonded retainers can serve in-mouth for decades.

7

There have been a few long-term studies of the long-term effects of bonded retainers on teeth.

7,

8 Dahl and Zachrisson

8 found no signs of dental caries or white spots after 3 - 6 years. Recently, Booth et al.

7 evaluated 60 patients who had permanent retainers in place for more than 20 years and concluded that orthodontists might recommend permanent retention to maintain the alignment of lower incisors.

In 1983, Zachrisson

9 introduced flexible spiral wire retainers (FSWRs). These retainers use a multistranded wire and include all anterior teeth. The flexibility of the wire reduces the concentration of stress within the bonding composite, thus minimizing the probability of subsequent failure.

10

Bearn

11 stated in a review that there is a trend toward the use of multistranded wires in the construction of bonded lingual retainers. The diameter of these wires varies between 0.015 inch and 0.032 inch and thinner wires are preferred for FSWRs. However, there has been no consensus regarding the most clinically effective diameter of multistranded wire.

12

The mode of failure for lingual retainers has been studied by several authors.

8,

13-

16 Artun and Urbye

13 found that the most common mode of failure was loosening between the wire and composite. Dahl and Zachrisson

8 evaluated the failure rates of FSWRs that were made with different wires and reported lower failure rates for five-stranded wires than for other wire types. They found that three-stranded wires came loose from the composite at a similar rate to failure by fracture. Bearn et al.

14 reported that the most common fracture mode was in the wire-composite interface, while Lumsden et al.

15 found that more fractures occur at the adhesive pad than at the wire-adhesive interface. Lumsden et al.

15 indicated that early fractures were the result of adhesive bond failures, and wire breakages were seen primarily in older retainers. Lie Sam Foek et al.

16 reported that the majority of the failures they observed occurred in the first 6 months after placement. The most common causes of these failures were debonding (37.5%), fracture plus debonding (1.4%), and fracture (0.7%).

Because bonded lingual retainers are intended to serve for long periods of time in the mouth, attempts should be made to increase the success rate of these devices. Loosening of the wire in bonded lingual retainers may result from cracks within the composite that arise from deformation of the interdental wire.

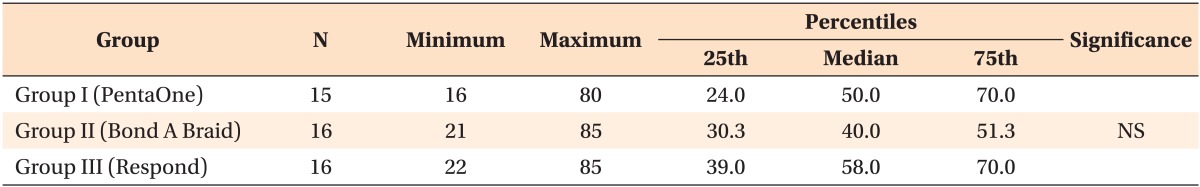

12 Wire choice may therefore be important for maximizing the success of lingual retainers. In this study, we tested three different wires used for lingual retainer fabrication in order to determine if they differ in (1) detachment force, (2) amount of deformation, (3) fracture mode, or (4) wire pull-out force.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ninety-four human lower incisor teeth were obtained from patients who were undergoing dental treatment. Teeth with caries, cracks or abnormalities were excluded. Soft tissue remnants were removed with a scaler and teeth were stored in thymol solution. Teeth were used within 1 month of extraction.

The study design was adopted from Cooke and Sherriff.

12 Pairs of teeth were matched to form a contact area that mimics the intraoral situation. Chemically cured acrylic resin was placed into plastic molds and the roots of the teeth were embedded in the acrylic. The roots were mounted so that the long axes of the teeth were perpendicular to the base of the molds. In total, 47 blocks were constructed.

The lingual aspects of the teeth were polished with fluoride-free pumice, etched for 30 seconds with 37% ortho-phosphoric acid (Transbond XT etching gel system; 3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA), rinsed with water for 30 seconds using a three-in-one syringe, and dried for 20 seconds using an oil-free air source. Primer (Transbond XT) was applied and left uncured, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. To provide best fit of the wire over the tooth, a gentle curve was given. The blocks of teeth were divided into 3 groups and a different type of wire was bonded to the teeth in each group. The wires used in each group were:

Group I: 0.0215-inch five-stranded wire (PentaOne; Masel Orthodontics, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Group II: 0.016 × 0.022-inch eight-stranded rectangular wire (Bond-A-Braid; Reliance Orthodontic Products, Itasca, IL, USA).

Group III: 0.0195-inch dead-soft coaxial wire (Respond; Ormco Corp., Orange, CA, USA).

A 10 mm length of test wire was cut and the midpoint of the wire was marked with a pencil. The test wire was then placed on the primed tooth surface. Great care was taken to place the wire parallel to the base of the mold and below the point of contact between the teeth in the mold. We used a commercially available adhesive set in order to standardize the amount of adhesive applied to each tooth (Mini-Mold; Ortho-Care Ltd., Bradford, UK). The composite was applied with wire bonder tips (dome shaped) and cured for 10 seconds with a light emitting diode curing unit (EliparFreelight-2; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA). The wire bonder tips have grooves that allow for placement of the wire in the middle of the composite bulk. The tip of the light curing unit was placed as close as possible to the surface of the tooth. Each composite bulk was 4 mm in diameter with a 1.5 mm depth. This provided a 12.6 mm2 bond area on each tooth. After curing, the teeth were stored in distilled water at room temperature for 24 hours before testing.

Debonding procedure

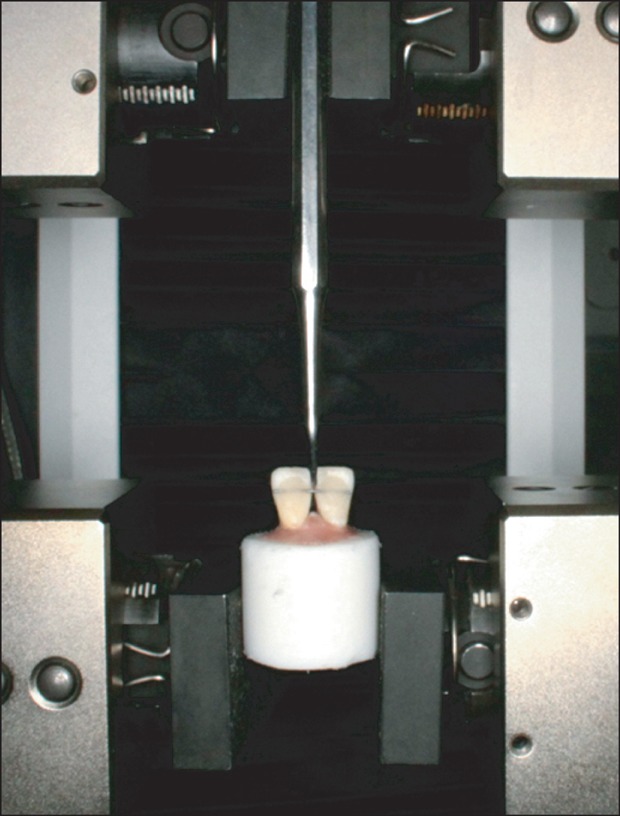

Embedded specimens were secured in a jig attached to the base plate of an Instron Testing Machine (Instron Corp., Norwood, MA, USA). A chisel-edge plunger was mounted in the movable crosshead of the testing machine and positioned so that the leading edge was aimed at the marked midpoint of the wire (

Figure 1). The chisel-edge was carefully placed so that it would not contact any part of the specimen. The crosshead speed was set to 1 mm/min and the maximum load necessary to debond the wire was recorded.

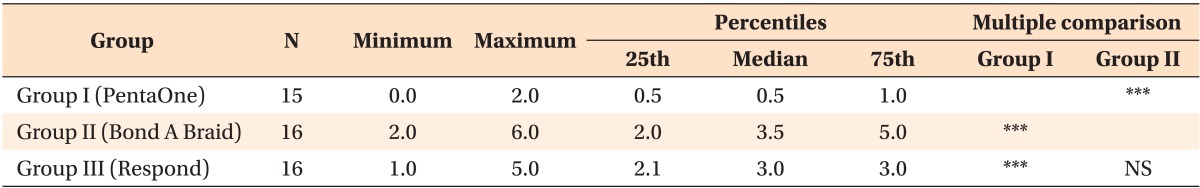

Wire deformation

After failure occurred, the composite over the wire was gently removed with a tungsten carbide bur. The wire was then positioned on graph paper and its deflection was assessed under an optical stereomicroscope (SZ 40; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at ×20 magnification. The amount of deflection was recorded in millimeters.

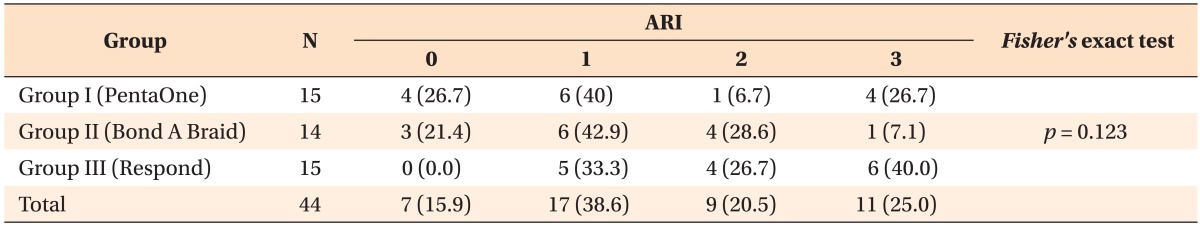

Fracture mode

We evaluated fracture mode on the side where the initial bond failure occurred using an optical stereomicroscope (SZ-40) at ×20 magnification. Remnant adhesive on the enamel surface was coded by one investigator (A.B.) who was blind to treatment group. We scored the fracture sites according to the Adhesive Remnant Index (ARI). In this system, fractures are ranked from 0 to 3, based on the amount of adhesive remaining after bracket removal

17,

18: 0, no adhesive remaining on the enamel surface; 1, less than 50% adhesive remaining on tooth; 2, more than 50% adhesive remaining on tooth; 3, all adhesive remaining on tooth surface.

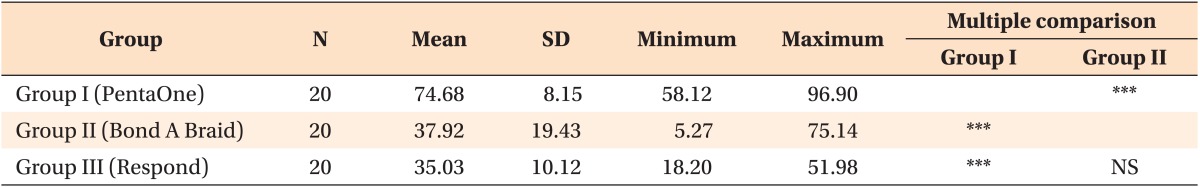

Pull-out test

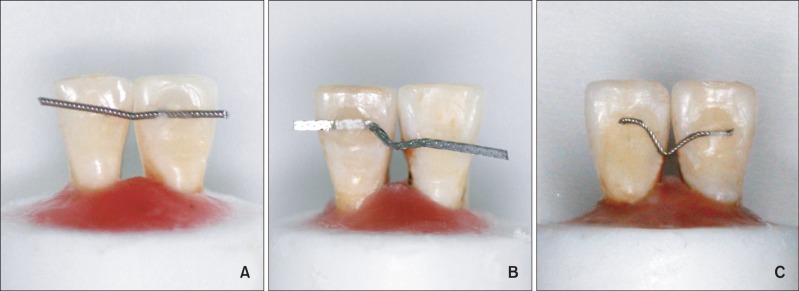

We used the method reported by Bearn et al.

14 to test pull-out force. Using molds, we prepared 60 cylindrical acrylic blocks that were 25 mm in diameter and 10 mm high. A 3 × 2 mm hole was drilled in the center of each block (

Figure 2). The drilled holes approximated the dimensions of the composite used clinically for lingual retainers.

15 Twenty acrylic blocks were assigned to each wire group. The hole in each block was filled with composite (Transbond XT) and one of the free ends of a 10 cm section of test wire was embedded in the composite. A second block with the same dimensions as the test block was used to ensure the accuracy of test wire placement, and to remove any excess composite. The placement block was fitted with a stainless steel alignment jig and a 1 mm hole through the center. Prepared test blocks were stored in distilled water at room temperature for 1 day before the test procedure. A testing machine (Instron Corp., Norwood, MA, USA) was placed in tensile mode and the crosshead speed was set to 10 mm/min. The test blocks were loaded into the machine and force was applied along the long axis of the wires. The force required to detach the wires from the composite was recorded.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Shapiro-Wilks normality test and Levene's variance homogeneity test were applied to the data. Detachment force and deformation data was not normally distributed and the groups did not have homogenous variances. We therefore used non-parametric tests to evaluate the data. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences between group detachment and deformation values. When a Kruskal-Wallis test indicated an overall difference between groups, Mann-Whitney U tests were used to examine the differences between individual groups. Fracture modes were analyzed using Fisher's Exact Test.

Pull-out data was found to be normally distributed and there was homogeneity of variance among the groups. Therefore, we used one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test to evaluate differences between the pull-out force of test groups. We calculated descriptive statistics, including the mean, standard deviation, minimum values, and maximum values for these measurements. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Bonded retainers are commonly used in order to prevent anterior lower arch crowding.

19 Patients with fixed retention show consistently better alignment at 5 and 10 years post-treatment than those patients without fixed retention, even though the Peer Assessment Rating scores of these patients were higher before treatment than the scores of those patients who were not fitted with fixed retention.

19 Moreover, fixed retainers have no harmful effects on oral hard and soft tissues.

19 Many composite and wire combinations are used for bonded lingual retainer fabrication.

In this study, we tested two types of dead-soft wires and a commonly used five-stranded stainless steel wire. These wires were selected because they were recommended in the literature. Bearn

11 recommended 0.0215-inch multistranded wires for fabricating FSWRs, based on a review of the literature. Aldrees et al.

20 found greater bond strength values with coaxial wire (PentaOne) compared to a solid chain retainer and Dahl and Zachrisson

8 stated that the results of their PentaOne tests were "particularly encouraging." We selected five-stranded stainless steel wire as a control because it has been used in various studies of fixed retainers and there is copious information about FSWRs constructed using this wire.

8,

9,

14,

20,

21 The other two test wires were dead-soft wires. Manufacturers claim that dead-soft wire is superior to five-stranded stainless steel wire for the construction of FSWRs because it is easily adaptable and minimizes the inadvertent tooth movement that is associated with active force wires. The dead-soft wires we selected included a rectangular eight-braided dead-soft wire and a stainless steel coaxial dead-soft wire. The manufacturer of the eight-braided wire states that intra-arch splinting with this wire prevents the torque control problems that can occur when round braided wires are used. They also state that the flattened wire increases patient comfort. The coaxial wire is recommended as an initial arch wire because of it applies light and gentle force. This wire is very flexible and possesses great spring-back characteristics. Manufacturers recommend dead soft Respond for bonded lingual retainers.

Zachrisson

9 recommended that FSWRs wire be 0.0195 inch or 0.0215 inch in diameter. In a later pa per, he indicated a preference for five-stranded wire because distortions were observed when thinner wires (0.0195-inch and 0.0175-inch) were used.

21 Moreover, Zachrisson

21 reported that 0.0215-inch multistrand dead-softened or heat-treated wires were unsafe for the maintenance of anterior tooth corrections, including rotations.

Retainer wires should be flexible enough to allow some degree of physiologic movement of retained teeth. This helps to maintain periodontal health and reduces the concentration of stress within the composite. The PentaOne group (group I), had significantly less deformation than the dead-soft wire groups (groups II and III). The smaller deformation of the PentaOne may cause force to be transferred to the teeth, thereby aiding periodontal health. Moreover, the forces of mastication or cleaning the area beneath the wire with dental floss may cause repetitious deformation that results in the breakage of the retainer wire. Wires that are more easily deformed may be more susceptible to breakage.

One of the main questions following an

in vitro study of this type is how well the tested forces match those that a retainer system must withstand in the oral cavity under clinical conditions. In this study, vertically directed force was applied to the interdental wire. According to Cooke and Sherriff,

12 when a vertical force is applied to a bonded wire, tension, shear, and torsion forces may occur simultaneously. On the other hand, bond strength studies are difficult to compare and interpret with previous studies.

10 This is because there is no standard protocol for the preparation and testing of materials and measurements of bond strength are highly variable. This is especially true for studies of lingual retainers, as there are few bond strength studies and testing models differ between them.

12,

14,

22 The findings of the current study should therefore be interpreted cautiously.

Pull-out tests were performed in order to evaluate the micromechanical adhesion between the composite and the wires. Bearn et al.

14 claimed that larger diameter wires with greater surface area require greater force to pull the wire out from composite. However, we found that although it was not the wire with the largest diameter, PentaOne wire had the highest mean resistance to displacement from composite. On the other hand, there may have been a lack of micromechanical adhesion between the composite and Respond wire, as the wire in group III slipped through the composite during testing.

We found no significant difference in the detachment force of the three wires tested. However, we observed a non-significant tendency of the detachment force to increase as the wire diameter decreases. This finding is consistent with the findings of Cooke and Sherriff

12 and may be due to the greater flexibility of thinner wires as compared to thicker wires. While this flexibility may appear to be advantageous, Zachrisson

9 reported that the wire fracture incidence decreases as wire diameter increases. We found no difference in mode of fracture among the investigated groups. The literature contains conflicting reports of common fracture modes. Failures have been found both at the composite-wire interface

12 and at the composite-tooth interface.

15 Loosening of the wire, wire fractures, and abrasive wear over the composite bulk were also reported.

8 We also found wire fractures in both dead-soft wire groups. Lumsden et al.

15 reported an increase in wire fractures as retainers aged.

Reynolds

23 suggested that bonded orthodontic attachments should be able to support loads of 60 - 80 kg/cm

2, if they are to withstand both the normal occlusal forces and the forces generated by orthodontic appliances.

10 These data are not applicable to bonded retainer wires.

12 There is little information in the literature regarding the minimum clinically accepted bond strength for bonded retainer wires.

12 We expressed force in Newton (unit of force), rather than in Pascal (unit of pressure), because the use of Pascal implies that the applied force was homogenously distributed across the surface area of bonds.

12 During the testing procedure, tension, shear, and torsion forces may occur simultaneously.

12

According to Cooke and Sherriff,

12 the age of the enamel, lingual morphology, and size of the tooth affect the forces exerted at the bonding interfaces. The present study may have been limited by the use of human lower incisor teeth that differed from one another in morphology and donor age. We chose to include teeth with various morphologies and donor ages in order to better mimic

in vivo situations.

The ultimate success of a bonded retainer is determined by the size and quality of the teeth and the occlusal load on the retainer.

10 Large tooth crowns have large bonding areas, enabling the load to spread over a wide area of enamel.

10 Although the size and morphology of the teeth used in this study were different from one another, the composite bulk placed over the teeth and the wires tested were standardized with commercially available molders. Thus, the same bonding area was constructed for each specimen. Moreover, the favorable working environment during bonding should be taken into consideration when findings of

in vitro studies are interpreted. Lie Sam Foek et al.

16 stated that as the working conditions for

in vitro studies are easier to manipulate than those experienced

in vivo, any differences observed in

in vitro studies are likely to be exacerbated

in vivo.

A large range of composites and wires are available for lingual retainer fabrication. In this study, five stranded coaxial wires exhibited less deformation and higher micro-mechanical resistance than dead-soft wire. Use of dead-soft wires in FSWRs may lead to problems in maintaining orthodontic treatment results. To evaluate the success rates of these wires, randomized controlled in vivo studies should be performed.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download