Abstract

Purpose

Celiac disease is a common non-communicable disease with varied presentations. Purpose of this study was to find the duodeno-endoscopic features in celiac disease and to compare duodeno-endoscopic and histological findings between typical and atypical celiac disease in children.

Methods

Hospital based observational study was conducted at Sir Padampat Mother and Child Health Institute, Jaipur from June 2015 to May 2016. Patients were selected and divided in two groups- typical and atypical celiac disease based upon the presenting symptoms. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and duodenal biopsy was performed for serology positive patients. Results were analysed using appropriate statistical test of significance.

Results

Out of 101 enrolled patients, 47.5% were male. Age ranged from 1 to 18 years. Study showed that 54.5% were typical and 45.5% were atypical. Patients presenting with atypical symptoms were predominantly of older age group. On endoscopy, scalloping, mosaic pattern, reduced fold height and absent fold height; and in histology, advanced Marsh stage were significantly higher in the typical group.

Conclusion

Awareness of atypical presentations as well as duodeno-endoscopic features may have considerable practical importance for the diagnosis of celiac disease in children. Scalloping, mosaic pattern, reduced fold height and nodularity are main endoscopic markers of celiac disease in children. Endoscopic markers of duodenal mucosa may be important in early diagnosis of celiac disease, in children subjected to endoscopy for atypical presentations or indication other than suspected celiac disease.

Celiac disease (CD) is defined as an immune mediated systemic disorder elicited by gluten and related prolamines in genetically susceptible individuals [1]. Worldwide, the disease affects approximately 1% of the general population, though this prevalence varies between countries [2]. Clinical features of CD vary considerably. Typical CD patients have predominantly gastrointestinal (GI) features such as chronic diarrhea, abdominal distension, and failure to thrive. Typical CD is common in children diagnosed within the first two years of life [345]. Many cases of CD present with predominantly non-GI signs and symptoms like anaemia, short-stature, aphthous stomatitis, recurrent abdominal pain, pica, delayed puberty, osteopenia, and dental enamel hypoplasia etc. (atypical CD). The most common atypical presentations of CD are iron-deficiency anaemia unresponsive to iron therapy and short stature [456].

Upper GI (UGI) endoscopy with small-bowel biopsy is a critical component of the diagnostic evaluation for persons with suspected CD and is recommended to confirm the diagnosis [7]. With increased availability of paediatric UGI endoscopy, many endoscopies are done for reasons other than suspected CD, and the detection of suggestive endoscopic features in the duodenum can alert endoscopists to take a duodenal biopsy and aid in increasing the diagnostic rate of the disease [8]. A number of macroscopic endoscopic markers of CD have been identified and includes [910]: 1) Scalloping-indented aspect of duodenal folds; 2) Absence or reduction of number of duodenal folds; 3) Mosaic pattern-micro nodular look of mucosa; 4) Grooves and fissuring of mucosa; 5) Sub mucosal vascular pattern; 6) Nodularity.

There is a lack of recent published literature on duodeno-endoscopic features in CD in children [91112] and we could not find any study comparing endoscopic findings in typical and atypical CD in children. Awareness of endoscopic markers is important so as not to miss cases of CD in the patients subjected to endoscopy for nonspecific symptoms. This study was conducted to find the duodeno-endoscopic features in CD children and also to compare duodeno-endoscopic and histological findings between typical and atypical CD in children.

This hospital based, cross-sectional observational study was conducted in the Sir Padampat Mother and Child Health Institute attached to Sawai Man Singh Medical College, Jaipur, India from June 2015 through May 2016. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Sawai Man Singh Medical College, Jaipur (IRB no. MC/ACAD/PG/2018/7720).

The minimum sample size was determined by considering difference at 95% confidence interval and 80% power based on previous data [4]. It was calculated to be 36 in each group using the EpiInfo 7 software (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). Children attending paediatric out-patient department or a gastroenterology clinic or admitted in the wards were prospectively enrolled after obtaining informed written consent from their parents.

Patients were divided in two groups: typical CD patients (group A) and atypical CD patients (group B) based upon the presenting symptoms [45]. Children with predominantly GI features such as chronic diarrhea, abdominal distension, and failure to thrive were included in the typical CD group. Patients were clinically examined and anthropometric assessment was done. Complete blood cell count, liver function tests, serum protein, albumin and serum calcium levels were done. Immunoglobulin A tissue transglutaminase (tTG) antibody was done by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method using Chorus Machine and a level of >15 IU/mL was considered positive.

UGI endoscopy and duodenal biopsy were performed for all tTG positive cases by single endoscopist (Dr. R.K. Gupta). A diagnosis of CD was made according to the criteria of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN 2012) [1].

UGI endoscopy was done using paediatric size flexible gastro duodenoscopes, Olympus GIF XP 150N & GIF Q 150 (Olympus Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with compatible biopsy forceps in GI endoscopy lab of the institute. After air insufflations, the macroscopic appearance of the mucosa at the level of the duodenal bulb, second and third parts of the duodenum were noted. Four pieces of mucosa were obtained from the second part of the duodenum and one from the duodenal bulb. Mucosal specimens were immersed in buffered formalin directly from the biopsy forceps. The severity of intestinal damage was graded by the pathologist as per the Marsh-Oberhuber classification [13].

The collected data were entered into Microsoft Excel sheet and analysed. Qualitative data have been expressed as proportions and quantitative data has been expressed as mean and standard deviation. Chi-square test for the qualitative data (and Fisher's exact test, wherever applicable) and independent sample t-test for quantitative data were used to test the statistical associations. The level of significance was kept at 95% for all statistical analysis. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed by a computer program for statistical analysis using SPSS 16.0 trial version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

There were 48 males and 53 females with male: female ratio of 1:1.1. Out of 101 children, 54.5% (n=55) presented with typical symptoms (group A) and remaining 45.5% (n=46) presented with atypical symptoms (group B). The mean age in group A was 4.83±3.05 years and was 7.71±3.46 years in group B, being significantly higher in the atypical group (p<0.001).

Anaemia was the most common symptom (54.5%), followed by chronic diarrhoea (51.5%) and short stature (50.5%). Anaemia and short stature were observed more among the atypical group than the typical group (p<0.001) as shown in Table 1. Other atypical presentations found were chronic pain abdomen (23.8%), constipation (6.9%), recurrent aphthous ulcer (3.9%), bone change in form of rickets (4.0%) and headache (3.9%). These features were more common in the atypical CD group. Dental enamel defects (2.0%), delayed puberty (2.0%), chronic urticaria (1.0%) and depression (1.0%) were found only in atypical group. One child presented as idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis with CD (Lane-Hamilton syndrome).

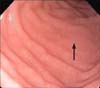

Most common duodenal endoscopic finding was scalloping (84.2%), followed by a mosaic pattern (67.3%), reduced fold height (36.6%) and nodularity (17.8%). Absent folds were observed in 7.9% of the subjects. The endoscopy was found to be normal in 7.9% of the cases. Images of some of the endoscopic findings observed in the present study are presented in Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Table 2 shows that scalloping, mosaic pattern, reduced fold height and absent folds were found more in the typical group as compared to the atypical group (p<0.05). Normal duodeno-endoscopic finding was found significantly higher in the atypical group (p<0.05).

Histo-pathological evaluation of intestinal biopsies revealed Marsh stage 2 in 2 patients (2.0%), stage 3a in 45 patients (44.6%), stage 3b in 34 patients (33.7%) and stage 3c in 20 patients (19.8%). Typical CD was significantly more likely to have a higher Marsh stage in histology finding (p<0.001) as shown in Table 3.

The CD is a highly prevalent, non-communicable disease in most parts of the world, including India (prevalence=1%), that can manifest at any age and shows varied clinical presentations [10]. The proportion of typical CD is higher in children than in adults [14]. Presentation of CD seems to have changed over the past few years and recently an upsurge has been observed for the atypical presentation [15].

Mean age was significantly higher in the atypical CD group than the typical CD group (p<0.001). Similar results were shown by Dinler et al. [4] and Kuloğlu et al. [16]. This difference could be because, typical presentations (diarrhea, abdominal distension) are usually noticed by the caretaker easily and so are brought to the notice of clinician at an early age. Atypical presentations are diagnosed at a later age, because of less awareness of varied non-GI presentations of CD, among treating paediatricians.

Chronic diarrhoea and abdominal distension were most common presentations in the typical CD cases, while anaemia and short stature were the most common presentations in the atypical CD cases. These results were similar as reported by Dinler et al. [4].

The most common duodeno-endoscopic finding in our study, was scalloping, followed by mosaic pattern, reduced fold height and nodularity. Our findings are quite similar to various previous studies [912171819]. In this study, endoscopy findings of scalloping, mosaic pattern and reduced fold height and absent fold height were found significantly more in the typical group as compared to the atypical group (p<0.05). Nodularity was less common in the typical CD group as compared to the atypical CD group, though the difference was not statistically significant. Normal duodeno-endoscopic findings was significantly more found in the atypical CD group than the typical CD group (p<0.05). These observations were comparable to that reported by Tursi et al. [19] except scalloping of duodenal folds. Scalloping was found significantly more common in the typical CD group in our study, while it was reported more commonly in atypical CD group by Tursi et al. [19]. This might be because of associated under-nutrition in our country or difference in ethnic and demographic profile (age and race). Moreover, the study by Tursi et al. [19] was in adult CD patients in Italy.

In the present study, histo-pathological evaluation of intestinal biopsies revealed a statistically significant correlation between histological grade of biopsied duodenal mucosa and clinical presentation (p<0.001). Dinler et al. [4] also found among children that total/subtotal villous atrophy was significantly higher in the typical group than in the atypical group. On the other hand, Brar et al. [20] found that the degree of villous atrophy in duodenal biopsies did not correlate with the mode of presentation which might be because of differences in age of the study population as we studied children while Brar et al. [20] studied adult CD patients.

Endoscopy with careful examination of the duodenum for the detection of endoscopic markers of CD may help in more detection of CD, especially in children subjected to endoscopy for atypical presentation or indication other than suspected CD. In CD, rarely duodenal biopsy may be normal because of patchy involvement of duodenal mucosa [1]. In such cases also, endoscopic markers may have considerable importance in identifying the potential sites for biopsy. In instances where pathology results will not be available in a reasonable duration, one may consider initiating a gluten-free diet when endoscopic markers suggestive of CD are seen in a symptomatic patient with positive celiac serology. In patients with suspected CD, biopsy should always be done, since in few the duodenum may have a normal endoscopic appearance.

The diagnosis may be made with certainty, if the results of the different diagnostic methods coincide, especially with the atypical form of the disease. The increasingly wide access to paediatric UGI endoscopy may be helpful in incidental diagnosis of CD. The awareness of paediatric gastroenterologists and endoscopists in recognizing endoscopic changes in duodenal mucosa may increase early diagnosis of CD in children as it will help in taking duodenal mucosal biopsy samples in cases, in which CD was not considered clinically. The main limitation of this study was being a single centre study. A more representative sample would need to include patients from other centres in this part of India. The relatively small numbers of cases is another limitation of the study.

This study suggests that awareness of endoscopic features as well as atypical presentations of CD may have considerable practical importance for the diagnosis of CD in children. In addition to biopsy & histopathology, endoscopic markers of duodenal mucosa are important in the early diagnosis of CD, in children subjected to endoscopy for atypical presentation or indication other than suspected CD. Scalloping, mosaic pattern, reduced fold height and nodularity are main endoscopic markers of CD in children.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Comparison of Histological Finding on Small Bowel Biopsy between Typical and Atypical Celiac Disease Groups (n=101)

References

1. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, Mearin ML, Phillips A, Shamir R, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012; 54:136–160.

2. Lionetti E, Catassi C. New clues in celiac disease epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and treatment. Int Rev Immunol. 2011; 30:219–231.

3. Branski D, Troncone R. Gluten sensitive enteropathy (celiac disease). In : Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, Nelson WE, editors. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders;2016. p. 1835–1838.

4. Dinler G, Atalay E, Kalayci AG. Celiac disease in 87 children with typical and atypical symptoms in Black Sea region of Turkey. World J Pediatr. 2009; 5:282–286.

5. Guandalini S. Celiac disease. In : Guandalini S, editor. Textbook of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. London: Taylor & Francis;2004. p. 435–450.

6. Sharma A, Poddar U, Yachha SK. Time to recognize atypical celiac disease in Indian children. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007; 26:269–273.

7. Garg K, Gupta RK. What a practitioner needs to know about celiac disease? Indian J Pediatr. 2015; 82:145–151.

8. Balaban DV, Popp A, Vasilescu F, Haidautu D, Purcarea RM, Jinga M. Diagnostic yield of endoscopic markers for celiac disease. J Med Life. 2015; 8:452–457.

9. Ravelli AM, Tobanelli P, Minelli L, Villanacci V, Cestari R. Endoscopic features of celiac disease in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001; 54:736–742.

10. Rosa RM, Ferrari Mde L, Pedrosa MS, Ribeiro GM, Brasileiro-Filho G, Cunha AS. Correlation of endoscopic and histological features in adults with suspected celiac disease in a referral center of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Arq Gastroenterol. 2014; 51:290–296.

11. Corazza GR, Caletti GC, Lazzari R, Collina A, Brocchi E, Di Sario A, et al. Scalloped duodenal folds in childhood celiac disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993; 39:543–545.

12. Kasirer Y, Turner D, Lerman L, Schechter A, Waxman J, Dayan B, et al. Scalloping is a reliable endoscopic marker for celiac disease. Dig Endosc. 2014; 26:232–235.

13. Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999; 11:1185–1194.

14. Poddar U. Pediatric and adult celiac disease: similarities and differences. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013; 32:283–288.

15. Gupta R, Reddy DN, Makharia GK, Sood A, Ramakrishna BS, Yachha SK, et al. Indian task force for celiac disease: current status. World J Gastroenterol. 2009; 15:6028–6033.

16. Kuloğlu Z, Kirsaçlioğlu CT, Kansu A, Ensari A, Girgin N. Celiac disease: presentation of 109 children. Yonsei Med J. 2009; 50:617–623.

17. Savas N, Akbulut S, Saritas U, Koseoglu T. Correlation of clinical and histopathological with endoscopic findings of celiac disease in the Turkish population. Dig Dis Sci. 2007; 52:1299–1303.

18. Piazzi L, Zancanella L, Chilovi F, Merighi A, De Vitis I, Feliciangeli G, et al. Diagnostic value of endoscopic markers for celiac disease in adults: a multicentre prospective Italian study. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2008; 54:335–346.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download