Abstract

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, though an uncommon surgical procedure in paediatric age group is still associated with a higher risk of post-operative bile duct injuries when compared with the open procedure. Small leaks from extra hepatic biliary apparatus usually lead to the formation of a localized sub-hepatic bile collection, also known as biloma. Such leaks are rare complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, especially in paediatric age group. Minor bile leaks can usually be managed non-surgically by percutaneous drainage combined with endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP). However, surgical exploration is required in cases not responding to non-operative management. If not managed on time, such injuries can lead to severe hepatic damage. We describe a case of an eight-year-old girl who presented with biloma formation after laparoscopic cholecystectomy who was managed by ERCP.

Cholelithiasis is a rare cause of paediatric abdominal pain [1]. Recently, with the use of abdominal Ultrasonography in evaluation of childhood abdominal pain, the incidence of cholelithiasis has been increasing [1].

Bile duct injuries are one of the most serious complications following hepatobiliary surgical procedures and have a major impact on the quality of life of the patients. These injuries usually present with life-threatening complications like peritonitis, sepsis, cholangitis or external biliary fistulae [2]. These patients also have a greater risk of developing secondary biliary cirrhosis. Early diagnosis and appropriate management is essential. Endoscopic techniques and radiological interventions can avoid laparotomy in about 78-100% of cases [2]. There is ongoing controversy as to whether these patients should be treated with surgical and non-surgical methods [2], especially in paediatric age group. When available, endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) can be diagnostic as well as therapeutic and may also help to avoid laparotomy.

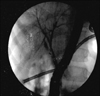

An eight-year-old girl presented with complaint of abdominal pain. She had history of laparoscopic cholecystectomy 17 days back at a private hospital for cholelithiasis. The abdominal pain had persisted from the post-operative period. There was no history of fever, jaundice or vomiting. At admission, her vitals were stable and there was no icterus. There was tenderness in the right hypochondrium and epigastrium. An 8×6 cm lump was palpable in the epigastrium and right hypochondrium (Fig. 1). Rest of the abdomen was soft. Complete blood haemogram, coagulation profile and Liver Function Tests were normal except for the raised alkaline phosphatase (1,342 units). Serum amylase and lipase levels were normal. Abdominal ultrasound suggested an 11×7×6 cm collection at sub-hepatic region. Abdominal contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a 10×9×8 cm collection encompassing the stomach and the left lobe of liver (Fig. 2). Ultrasound guided percutaneous insertion was done and approximately 500 mL of bilious fluid was drained. ERCP showed small leak from the right posterior hepatic duct and it was treated with stenting (Fig. 3). The anatomy of the biliary tract was normal. Drainage gradually decreased from the abdominal drain and it was removed after 6 days. The biliary stent was removed after 6 weeks. The patient is doing well on follow up since 3 years.

Bile duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy ranges from mild to severe and can lead to serious and disastrous consequences. In spite of the progress in laparoscopic surgery, the cases of bile duct injuries are often missed. The incidence has been reported to be between 0.3% and 0.6% [3]. The predisposing factors to such injuries are acute cholangitis, gangrenous cholecystitis, perforated gall bladder, sclero-atrophic gall bladder, Mirrizzi's syndrome, duodenal ulcer, pancreatic neoplasm, pancreatitis, hepatic neoplasm and infections, fibrosis in triangle of Calot, obesity, local hemorrhage, variant anatomy, fat in porta hepatis and the presence of anomalous duct or vessel.

The usual cause of bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy include the cystic duct stump caused by the misplacement of the clips, clipping or ligation of the bleeding vessels, excessive traction on the gall bladder which tents the common bile duct (CBD), injury to the CBD and from the accessory duct or the small bile ducts of the gall bladder bed. The frequencies of sites of these injuries are CBD (67%), common hepatic duct (15%), hilar hepatic ducts (11%) and the cystic duct (2.7%) [4].

The most common anatomic variant of the biliary system (13-19%) is the drainage of the right posterior duct into the left hepatic duct before its confluence with the right anterior duct [4]. The second common variant (12%) is that the right posterior duct will not pass the right anterior duct posteriorly, but will empty into the right aspect of the right anterior duct. The third common variant (11%) is the triple confluence anomaly, characterized by simultaneous emptying of the right posterior duct, right anterior duct, and left hepatic duct into the common hepatic duct.

Bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy include excision, division, narrowing and occlusion. These can cause intra-abdominal collection, fistula formation or even life threatening peritonitis if the leak is large. The incidence of such bile leaks after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is 0.2-2% [3]. Less severe injuries causing small flow lead to the formation of a localized or sub-hepatic collection or biloma [3]. Unusual locations of biloma in the abdominal wall or even intra-hepatic sub-capsular biloma have been reported [5].

Bilomas after laparoscopic cholecystectomy are relatively uncommon and their incidences are approximately 2.5% [3]. A biloma is a well-encapsulated bile fluid mass; caused by damage to the biliary tree and consequent bile leakage [6]. The mechanism of biloma formation is bile leakage which is due to either a damaged biliary tree or a ruptured gallbladder. The bile extravasation induces a process of foreign body granulomatous reaction [6]. The usual presentation is right upper quadrant or epigastric pain (92%), jaundice (80%), deranged liver functions (70%), abdominal distention due to the collection, fever and leucocytosis. Sometimes, the extrinsic compression to the bile duct or duodenum can cause obstructive jaundice or gastric outlet obstruction, respectively [7]. The detection of biloma formation can be delayed; this stresses the importance of giving attention to the symptoms of persistent abdominal pain, fever or leucocytosis in a patient who has undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy. An abdominal ultrasound should be done to exclude any intra-abdominal collection [3].

Early and accurate diagnosis is mandatory to determine the appropriate management. Modern imaging techniques like magnetic resonance imaging, CT, Ultrasound imaging and other interventional modalities like ERCP and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography are the useful tools to make the accurate diagnosis of the lesion and also enable the optimal minimally invasive treatment [3]. These modalities help to avoid laparotomy in most cases and are the method of choice.

The biloma can be managed by percutaneous drainage placed under imaging guidance. Small leaks resolve in few days by simple drainage. The sites of the leak can be delineated by standard cholangiographic techniques. Larger leaks require stenting by ERCP.

However, major biliary injuries usually require surgical intervention. Delayed management and long lasting chronic biliary obstruction is associated with significant hepatic damage. Consequences of these injuries are postoperative fluid collection, stricture, biliary peritonitis, sepsis, multiple organ failure, biliary cirrhosis and hepatic failure.

Review of such cases in literature shows that minor bile leaks can be managed non-surgically by percutaneous drainage combined with ERCP; surgical exploration is required in cases not responding to non-operative management (Table 1) [235789].

For biliary tract injuries recognized during postoperative period, the treatment of choice is percutaneous drainage and ERCP stenting as was in this case. Thus surgical exploration and its associated morbidity can be avoided.

Bile duct injuries causing biloma can be successfully managed non-operatively by percutaneous drainage of the collection and ERCP guided stenting of the injured duct. This leads to a decrease in hospital stay and recovery time. The associated morbidities of surgery are also thereby avoided.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Abdominal computed tomography scan image showing a large collection of 10×9×8 cm encompassing stomach and left lobe of liver.

References

1. Oak SN, Parelkar SV, Akhtar T, Pathak R, Vishwanath N. Role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children. J Indian Assoc Paediatr Surg. 2005; 10:92–94.

2. Eum YO, Park JK, Chun J, Lee SH, Ryu JK, Kim YT, et al. Non-surgical treatment of post-surgical bile duct injury: clinical implications and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:6924–6931.

3. Pavlidis TE, Atmatzidis KS, Papziogas BT, Galanis IN, Koutelidakis IM, Papaziogas TB. Biloma after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Gastroenterol. 2002; 15:178–180.

4. Mortelé KJ, Ros PR. Anatomic variants of the biliary tree: MR cholangiographic findings and clinical applications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001; 177:389–394.

5. Cervantes J, Rojas GA, Ponte R. Intrahepatic subcapsular biloma. A rare complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994; 8:208–210.

6. Vazquez JL, Thorsen MK, Dodds WJ, Quiroz FA, Martinez ML, Lawson TL, et al. Evaluation and treatment of intraabdominal bilomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985; 144:933–938.

7. Mansour AY, Stabile BE. Extrahepatic biliary obstruction due to post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy biloma. JSLS. 2000; 4:167–171.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download