Abstract

Meckel diverticulum (MD) is one of the most common congenital gastrointestinal anomalies and occurs in 1.2-2% of the general population. MD usually presents with massive painless rectal bleeding, intestinal obstruction or inflammation in children and adults. Suppurative Meckel diverticulitis is uncommon in children. An experience is described of a 3-year-old girl with suppurative inflammation in a tip of MD. She complained of acute colicky abdominal pain, vomiting and periumbilical erythema. Laparoscopic surgery found a relatively long MD with necrotic and fluid-filled cystic end, which was attatched to abdominal wall caused by inflammation. Herein, we report an interesting and unusual case of a suppurative Meckel diverticulitis presenting as periumbilical cellulitis in a child. Because of its varied presentations, MD might always be considered as one of the differential diagonosis.

Meckel diverticulum (MD) is the most common congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract, caused by the incomplete degeneration of an omphalomesenteric duct [1]. It occurs in 1.2-2% of the population. It is usually asymptomatic but is accompanied by complications in about 4% of MD cases. The clinical presentation of MD varies, including bleeding, vomiting, abdominal pain, irritability, and abdominal distension [2,3]. The variety of clinical presentations depends on age, and the length of the diverticulum and ectopic tissue [4]. The most common presentation of MD in children is painless bleeding [5,6]. Another common symptom in children is intestinal obstruction [7]. Diverticulitis is the next common complication of MD, and it occurs as a result of acute inflammation [4] and is more common in adults than in children [8]. Because of its varied clinical presentation, the diagnosis of MD is usually challenging [9]. A simple abdominal X-ray, barium study, and abdominal ultrasonography (USG) are rarely useful in diagnosis. Significant painless rectal bleeding in an infant or a child might suggest the existence of MD and Meckel's scan might help diagnose MD in that event. However, sometimes MD may be detected incidentally during surgery, especially under circumstances of uncommon presentations [10].

A 3-year-old female was brought to our emergency room (ER) with abdominal pain and periumbilical erythema. One day earlier, the abrupt onset abdominal pain had disturbed her sleep. The pain was sharp, colicky, located in the periumbilical area, and aggravated during movement. The associated symptoms were nausea and vomiting. The vomiting was non-bile-tinged, projectile, and consisted of food materials, occurring eight times in a two-hour span. Initially, she was given intravenous hydration and prokinetics at an outside hospital. Her abdominal pain and vomiting improved after hydration and she was discharged. In the afternoon, she was brought to our ER again. Poor feeding and defecation difficulty were noted. On her admission at our hospital, her abdominal pain had returned, and it was so severe, she could not stand. The patient's past medical history was not remarkable.

On physical examination, her body temperature was 37.2℃, with a blood pressure of 90/50 mmHg and a heart rate of 132 beats per minute, with normal respiration and oxygen saturation. Her abdomen was soft, with decreased bowel sounds, mild distension, and no palpable mass; however, tenderness and rigidity with palpation and erythema around the umbilicus (Fig. 1) were observed. A review of her laboratory workup revealed a leukocytosis of 13,760 white blood cells (WBC) per microliter and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (84.7 mg/L), while the remainder of the complete blood count, electrolyte level, and liver biochemistry were within normal limits.

A simple abdominal X-ray showed bowel dilatations (Fig. 2). An abdominal USG revealed a cystic mass under the umbilicus, composed of heterogeneous materials (Fig. 3). A computed tomography (CT) scan of her abdomen was performed and a "cystlike fluid and gas collection measuring 2.9×1.9 cm in transverse dimension" in the anterior aspect of the midline abdomen was found (Fig. 4). The upper aspect of this fluid and gas was attached to the umbilicus. Based on this CT scan, the possibilities considered in the differential diagnosis included: an abscess in MD or a mesenteric cyst. After the radiologic studies, we decided antibiotic and surgical management. She was taken antibiotics intravenously with cefotaxime and metronidazole. A laparoscopic operation was performed on her admission day and the cystic mass filled with suppurative inflammatory fluid was found to adhere to the midline of the anterior abdominal wall in the area of the umbilicus and also connected with an 8 cm-length diverticulum from the small bowel, 7 cm from the ileocecal valve (Fig. 5). The tip of diverticulum was dilated and looked like a cystic mass on an abdominal USG and CT because of suppurative inflammatory fluid collection. The wall of dilated diverticular tip showed necrosis but perforation was not happened yet. Segmental bowel resection and re-anastomosis was done. The pathologic findings revealed that the ectopic gastric mucosa was associated with ulceration and serositis (Fig. 6). The result of closed pus culture was Escherichia coli. Periumbilical erythema was improved 1 day after surgery and she could eat some liquid food on 5 days after surgery. After operation, her laboratory findings were improved and as follows: 11.7 g/dL of hemoglobin, 36% of hematocrit, 6,440/mL of WBC, and 426,000/mL of platelet. A level of CRP was 11.1 mg/L (reference range: 0-5). It was still higher than reference range after 5 days of the operation, but it was steadily decreasing. She was discharged in good general condition after 6 days of admission.

The persistence of the ductal communication between the intestine and the yolk sac beyond the embryonic stage may result in several anomalies of the vitelline duct. Those anomalies are MD, vitelline cyst, umbilical-intestinal fistula, and omphalomesenteric band [10]. The most common form of a remnant vitelline duct is a MD and it occurs about 2% of the general population. Symptomatic MD is more common in children than adults, and in a study, 75% of symptomatic MD among 58 patients was diagnosed in patients under the age of 5 [2].

The most common presentations of MD in children are bleeding and intestinal obstruction [2,3,9]. Diverticulitis is the third most common presentation seen in adults (28%) and it is related to a 10% perforation of the MD [4]. In Korean reports, 9% of childhood symptomatic Meckel diverticula presents as diverticulitis [2,9]. Several cases of Meckel diverticulitis with perforation have been reported in the world [11,12,13,14]. However, diverticulits mimicking periumbilical cellulitis in children has not been reported. Our case was diagnosed as diverticulitis with suppurative inflammatory fluid collection in the lumen and the tip of MD was adherent to the abdominal wall around the umbilicus because of inflammation. Erythema and tenderness around umbilicus could induce us to make an early diagnosis and prevent the development of peritonitis. However, periumbilical erythema and tenderness led to confusion in making the diagnosis of MD. At first, we considered our case to be one of periumbilical cellulitis and inflammation of the urachal cyst. But, an abdominal USG revealed that the attached cyst mass at the abdominal wall extended to the intestine. Our case showed progressive abdominal wall rigidity, and a laparoscopic operation was performed. The cystic mass was adherent at the midline to the anterior abdominal wall in the area of the umbilicus due to inflammatory spreading, and also had an 8 cm-length stalk from the small bowel to 7 cm from the ileocecal valve on the antimesenteric aspect (Fig. 5).

The dimensions and length of MD have been associated with symptom occurrence from a previously asymptomatic MD. Patients with diverticular lengths greater than 2 cm are more prone to develop symptoms [4]. Long and thin-based MD is more likely to be symptomatic than a short or broad-based variety [15]. In our case, a long and narrow-based MD with an abscess at the tip was noted.

Ectopic gastric mucosa associated with ulceration and serositis was noted on the pathologic examination (Fig. 6). Painless rectal bleeding usually might be caused by peptic ulceration secondary to acid production by the ectopic gastric mucosa within the MD [10]. However, our case presented as suppurative inflammation of MD rather than painless rectal bleeding, despite the existence of ectopic gastric mucosa in MD. We tentatively suggested that a previous E. coli infection may have provoked inflammation and suppurative fluid collection in our case based on the results of pus culture. Because MD can cause diverse gastrointestinal symptoms, like in our case, and occurs in 2% of the general population, MD should always be considered as one of the differential diagnoses when diverse gastrointestinal symptoms are presented.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Periumbilical erythema. This figure shows erythematous skin change around umbilicus and a slightly distended abdomen. She presented with abdominal tenderness and rigidity at that time.

Fig. 3

The finding of an abdominal ultrasonography (USG). Cystic mass (circle) under the umbilicus with heterogeneous materials was noted on abdominal USG. The cystic mass extended into the intestine.

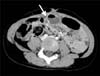

Fig. 4

The finding of an abdominal computed tomography (CT). Axial view CT scan showing the intra-abdominal, fluid- and air-filled cystic structure attached at the umbilicus (white arrow).

Fig. 5

Operative finding. The cystic structure was attached to the ileum (small bowel) via an 8 cm-stalk at the antimesenteric aspect. The tip of the structure was dilated and attached to abdominal wall due to inflammation. The tip of Meckel diverticulum was not perforated but was easily torn during separation from abdominal wall.

References

1. Turck D, Michaud L. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding. In : Walker WA, editor. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. 4th ed. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker Inc.;2004. p. 273–274.

2. Lee YA, Seo JH, Youn HS, Lee GH, Kim JY, Choi GH, et al. Clinical features of symptomatic meckel's diverticulum. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006; 9:193–199.

3. Huang CC, Lai MW, Hwang FM, Yeh YC, Chen SY, Kong MS, et al. Diverse presentations in pediatric Meckel's diverticulum: a review of 100 cases. Pediatr Neonatol. 2014; 55:369–375.

4. Park JJ, Wolff BG, Tollefson MK, Walsh EE, Larson DR. Meckel diverticulum: the Mayo Clinic experience with 1476 patients (1950-2002). Ann Surg. 2005; 241:529–533.

5. Menezes M, Tareen F, Saeed A, Khan N, Puri P. Symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum in children: a 16-year review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008; 24:575–577.

6. Tseng YY, Yang YJ. Clinical and diagnostic relevance of Meckel's diverticulum in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2009; 168:1519–1523.

7. Durakbasa CU, Okur H, Mutus HM, Bas A, Ozen MA, Sehiralti V, et al. Symptomatic omphalomesenteric duct remnants in children. Pediatr Int. 2010; 52:480–484.

8. Chen JJ, Lee HC, Yeung CY, Chan WT, Jiang CB, Sheu JC, et al. Meckel's diverticulum: factors associated with clinical manifestations. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2014; 2014:390869.

9. Rho JH, Kim JS, Kim SY, Kim SK, Choi YM, Kim SM, et al. Clinical features of symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum in children: comparison of scintigraphic and non-scintigraphic diagnosis. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2013; 16:41–48.

10. Kahn E, Daum F. Anatomy, histology, embryology, and developmental anomalies of the small and large intestine. In : Sleisenger MH, Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors. Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier;2010. p. 1615–1642.

11. Spasojevic M, Naesgaard JM, Ignjatovic D. Perforated midgut diverticulitis: revisited. World J Gastroenterol. 2012; 18:4714–4720.

12. Spiliopoulos D, Awala AO, Peitsidis P, Foutouloglou A. Simultaneous Meckel's diverticulitis and appendicitis: a rare complication in puerperium. G Chir. 2013; 34:64–69.

13. Wasike R, Saidi H. Perforated Meckel's diverticulitis presenting as a mesenteric abscess: case report. East Afr Med J. 2006; 83:580–584.

14. Grasso E, Politi A, Progno V, Guastella T. Spontaneous perforation of Meckel's diverticulum: case report and review of literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2013; 84:pii: S2239253X13020902.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download