Abstract

Methods

This cross sectional study was conducted at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University Hospital. Bangladesh, over a period of 3 years. One hundred consecutive children of WD between 3 to 18 years of age were evaluated.

Results

Mean age was 8.5±1.5 years. Male female ratio was 2:1. Ninety-one percent of patients were Muslim and 9% Hindu. A total of 53% cases of hepatic WD presented between 5 to 10 years of age and most of the neurologic WD manifested in 10-15 years age group. Sixty-nine children presented only with hepatic manifestations, 6 only with neurological manifestations, 14 with both hepatic and neurological manifestation, 10 children was asymptomatic and 1 patient presented with psychiatric features. WD presented as chronic liver disease (CLD) in 42%, CLD with portal hypertension in 34%, acute hepatitis in 20% and fulminant hepatic failure in 4% cases. Stigmata of CLD were found in 18% patients. Keiser-Fleischser ring was found in 76% total patients. Elevated serum transaminase was found in 85% cases, prolonged prothrombin time in 59% cases and hypoalbuminaemia in 53% cases. A total of 73% patients had low serum ceruloplasmin, basal urinary copper of >100 µg/day was found in 81% cases and urinary copper following penicillamine challenge of >1,200 µg/day was found in 92% cases.

Wilson's disease (WD) is an autosomal recessive condition affecting copper metabolism. Impaired excretion of copper through bile and decrease incorporation into ceruloplasmin causing excessive copper accumulation in different organs like liver, brain and cornea. In WD main defect remains in copper transporter protein adenosine triphosphatase (ATP) 7B, a P-type ATPase resulting from gene mutation in chromosome 13. The worldwide prevalence of WD is 1 in 30,000 and the heterozygote carrier rates are about 1 in 90 persons [1]. Prevalence of WD in Bangladesh is not known.

The clinical presentation of WD varies widely. Before 10 years of age, 83% patients of WD present with hepatic manifestations and 17% with neuropsychiatric manifestations; between 10 and 18 years, 52% present with hepatic and 48% with neuropsychiatric symptoms. After the age of 18 years, 75% patients present with neuropsychiatric features and 25% patients develope liver disease [2]. The hepatic presentation also varies. Children may be asymptomatic and transaminasaemia may be an incidental finding [3]. Patient may presents with compensated or decompensated chronic liver disease (CLD). Sometimes splenomegaly due to portal hypertension may be the only finding [4]. Acute liver failure may be one of the presentations of WD and usually follow a bad outcome [5]. Patients provisionally diagnosed as autoimmune hepatitis and not responding to standard therapy should be investigated for WD because raised serum immunoglobulins level and autoantibodies may be found in both the conditions [6]. Coomb's negative haemolytic anaemia is a frequent feature of WD. Hemolysis in WD may be acute or chronic, as single episode or recurrent [3]. Neuropsychiatric features usually develope in adult but may occur in children [7]. Early neurological features are behavior abnormalities, deterioration of school performance or difficulties in activities requiring handeye coordination [78]. Other neurological manifestations include deterioration of handwriting, drooling, dysarthria, dystonia, and spasticity. Seizures are infrequent in WD [9]. Common psychiatric abnormalities are depression, anxiety or even frank psychosis [10]. WD with neurological manifestation may or may not have symptomatic liver disease [11]. Occassionally patient of WD may present with renal stones, early osteoporosis, cardiomyopathy, pancreatitis, hypo parathyroidism, etc [1213].

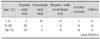

Prompt treatment is needed to prevent progression of neurological and hepatic damage. For this purpose, immediate diagnosis is needed. There is no single test for diagnosis of WD. Due to absence of definitive diagnostic test, identification of cases of WD is based on the combination of clinical finding, laboratory parameter and mutation analysis. Unfortunately, genetic diagnosis is not available in Bangladesh. WD disease can be diagnosed by using the scoring system developed at the 8th International Meeting on Wilson's Disease in Leipzig, 2001 (Table 1) [14]. If proper treatment can be started before irreversible liver damage or neurological impairment, near normal life expectancy is possible [4].

It was a cross sectional descriptive study. The study was conducted at the Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, during the period of January, 2011 through December, 2013. One hundred consecutive cases of WD were studied. Patients of either sex or age range from three to eighteen years were studied. Patients presented with liver disease, seeking treatment at the Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition in the University Hospital, were investigated for infective, metabolic, autoimmune hepatitis and celiac disease. Detailed medical and family history was taken. Thorough physical examination was done including presence of jaundice, hepato splenomegaly, ascites and signs of liver failure. Neurologic and psychiatric assessments were done. Slit lamp examination of eyes by an ophthalmologist was done in all cases to identify Kayser Fleischer (KF) rings and/or sunflower cataract. Complete blood count was done to see haemoglobin level and features of haemolysis. Liver function tests were done to see the extent and progression of liver disease. Serum ceruloplasmin, 24 hours urinary copper as baseline and after penicillamine challenge were done. Coomb's test was done in all the cases of WD. All the above mentioned tests were performed using standard laboratory methods. Liver biopsy was not done because of unavailability of testing of hepatic copper in Bangladesh. Sibs of diagnosed wilsonian patients were also investigated similarly. WD was diagnosed on the basis of diagnostic scoring system proposed in Leipzig, 2001 (Table 1) [14]. Diagnosis of WD was done on the basis of presence of a score of 4 or more. Hepatic copper estimation and mutation analysis cannot be done because of unavailability of the tests in Bangladesh. CLD was diagnosed on the basis of long history of jaundice, presence of stigmata of CLD and biochemically higher aspartate aminotransferase (AST) than alanine aminotransferase (ALT) with low serum albumin. Acute hepatitis was diagnosed as acutely occurring jaundice with prodromal symptoms in previously apparent healthy individual. Acute hepatic failure was diagnosed by prolongation of prothrombin time more than 20 seconds not responded to parenteral vitamin K1, ratio of alkaline phosphatase to total serum bilirubin of <4 and ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to ALT of >2.2. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS Statistics ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Frequency analysis was done and results were expressed as mean, median, range and percentage.

During the study period 100 patients of WD were analysed. Scores of the patients of WD according to the scoring system at 8th International Meeting on WD were 4 to 5 in 64% patients, 6 to 7 in 22% and >7 in 14% patients. Study population was 4 to 15 years with mean age 8.5±1.5 years. Male female ratio was about 2:1. Ninty one percent of patients were Muslim and 9% were Hindu. Consanguinity of marriage was found in 30% of cases. Seven parents were first degree cousin. Family history of CLD was found in 15% of patients. Regarding presentation of WD 69% patients presented only with hepatic manifestation, 6% only with neurological features and 14% manifested both hepatic and neurological disease. The age of hepatic WD was between 5 to 10 years and that of neurological WD was after 10 years. Asymptomatic child was identified during family screening (Table 2).

Hepatic presentations of WD in this study include CLD with or without portal hypertention, acute hepatitis and fulminant hepatic failure. Among the 83 hepatic cases (including hepatic only and hepatic with neurological features) CLD with or without portal hypertension is the main presentation (Table 3). Jaundice was present in 45% patients. Sixty one percent of patients had hepatomegaly and 35% had splenomegaly. Ascites was present in 38% patients. Stigmata of CLD was in only 18% patients. Common stigmata was thenar and hypothenar wasting (n=8). Spider angioma was found in two patients. Clubbing was found in only one patient. Gynaecomastia was also found in one patient. KF ring was found in 76% of the total patients. KF ring was present in 84% of the hepatic only wilsonian patients and in 90% of neurologic wilsonian patients. Asymptomatic and psychiatric patient had no KF rings. Sunflower cataract was found in 2 cases. Both patients with sunflower cataract presented with hepatic manifestation. One patient later developed pancreatitis.

Biochemical tests revealed higher serum AST level than ALT level. Prothrombin time ranges from normal to 50 seconds (Table 4).

Serum cereloplasmin was normal in 27% patient and rest of them had low serum ceruloplasmin. Baseline 24-hour urinary copper excretion was more than normal in 100% patients. Twenty-four-hour urinary copper after penicillamine challenge >200 µg/day was in 99% cases and >1,600 µg/day in 58% cases (Table 5).

In 28 cases esophageal varices was found by upper gastrointestinal tract (GIT) endoscopy. WD patient with hepatic presentations were given zinc sulphate along with penicillamine. All patients with neurological manifestation as well as asymptomatic cases were maintained on zinc.

This study included 100 patients who were analysed clinically and biochemically. Mean age was 8.5±1.5 years. Wilson disease is rare before 5 years of age though there is report of occurance of disease at 3 years of age [15]. The youngest patient in present study was a boy of 4 years who was asymptomatic and identified during family screening. Kleine et al. [16] evaluated 28 Brazilian children, whose mean age at diagnosis was 10 years. Male are more than the female in the present study. Similar observation was also made by some other researchers [17181920]. Merle et al. [21] found female preponderance. Some observer found no sex difference about the occurrence of WD [7]. Male preponderance may be due to the facts that parents give more importance for male child to seek medical care. Ninety-one percent of patients were Muslim and 9% Hindu. In Bangladesh, Hindus are 10% of total population. Disease frequency is almost equal in both religious groups. Consanguinity of marriage was found in 30% patients. Consanguinity of marriage is a feature of WD as because it is an autosomal recessive condition. Saito found WD to be more prevalent among the child of consanguineous parents in Japan [22].

Among the hepatic patients, 69% had only hepatic involvement and 14% had both hepatic and neurologic manifestation similar to observation of El-Karaksy et al. [17]. But a lower prevalence of 65% and 22% respectively was reported by Medici et al. [23]. High prevalence may be explained by the age of study group, where hepatic manifestations predominate in childhood. Moreover, this study was conducted at Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition where most of the patients come with hepatic complaints.

CLD is the main presentation of WD. Following copper deposition, hepatocytes become destroyed and result in fibrosis and cirrhosis. Portal hypertension is the result of distortion of hepatic architecture. Though WD may present with acute hepatitis, they ultimately develope chronicity [2]. WD causes hepatic failure in about 5% patients [4]. History revealed that 34% patient had gastrointestinal haemorrhage due to ruptured esophageal varices. GIT haemorrhage may also be due to coagulopathy resulted from impaired coagulation factor synthesis, qualitative or quantitative deficiency of platelets or due to peptic ulcer resulted from gastric erosion.

The prevalence of gynaecomastia in cirrhotic patients in adults has been reported in one study to be 44% [24]. Spider angioma was found in 33% cases and clubbing in 24% cases of cirrhosis [2526]. In the present study thenar and hypothenar wasting was found in 8%, spider angioma in 2% and clubbing and gynaecomastia in 1% cases each. Spider angioma and gynaecomastia is due to impaired estradial metabolism in liver [25]. Clubbing is present in primary biliary cirrhosis and CLD with hepatopulmonary syndrome [27]. Clubbing develops due to release of platelet derived growth factor from aggregated platelets in nail bed [26]. Presence of KF rings are reliable sign in WD but it may also be found in chronic active hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, chronic cholestasis and cryptogenic cirrhosis. KF rings consist of copper granules deposited in the descemet's membrane in limbic region of cornea. Sunflower cataracts are usually associated with KF rings and they are found in anterior lens capsule with spoke radiation towards the lens periphery [28]. ALT was raised in 92% patients. Serum AST level is higher than serum ALT in this study. It is a feature of WD. Serum AST to ALT ratio >2.2 is a feature of fulminant hepatic failure due to WD [1]. ALT and AST are cytosolic enzyme and level may be normal or low in liver failure and in advanced liver disease. Ioris found normal ALT in 5.5% of patients [29]. El-Karaksy et al. [17] found median serum bilirubin of 2.9 mg/dL and median serum albumin of 2.4 gm/dL in his study on hepatic WD. In present study, median total serum bilirubin was 1.9 mg/dL, median prothrombin time 20.50 seconds and median serum albumin of 3.5 gm/dL. Liver function was not altered in a good number of patients. This may be due to the fact that these patients were picked up earlier in the disease course.

Seventy three percent patients had lower than normal serum ceruloplasmin. Ceruloplasmin is an acute phase reactant produced in liver. Low serum ceruloplasmin was found in WD, protein losing enteropathy, nephrotic syndrome, malnutrition, Menke's disease, etc [30]. Greater than normal may be found in pregnancy, oral contraceptives usage, acute and chronic inflammation, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia and obsessive compulsive disorder [303132]. Dhawan et al. [33] reported normal serum ceruloplasmin in 20% patient. In our study basal 24 hour urinary copper of more than 40 µgm and post penicillamine 24 hours urinary copper more than 200 µgm (more than 5 times upper limit normal) was found in almost all the patients. In penicillamine challenge test, 58% had 24 hours urinary copper of >1,600 µgm/day. El-Karaksy et al. [17] found basal urinary copper more than >100 µgm/day in 53% patients. After penicillamine challenge it was found that 24 hours urinary copper excretion of <1,000 µgm/day in 15%, 1,000 to 1,600 µgm/day in 36.4% and >1,600 µgm/day in 48.5% patients. Limitations of this study are, hepatic copper estimation and mutation analysis could not be included in diagnostic scoring system.

WD is a treatable metabolic cause of liver disease. Majority of studied WD children presented with hepatic manifestation of which 76% presented with CLD. Any child with jaundice after 3 years of age should be evaluated for WD.

Figures and Tables

Table 3

Hepatic Presentation of Wilson's Disease (Including Hepatic Only and Hepatic with Neurological Presentation) (n=83)

References

1. European Association for Study of Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Wilson's disease. J Hepatol. 2012; 56:671–685.

2. Sokol RJ, O'connor JA. Copper metabolism and copper storage disorders. In : Suchy FJ, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF, editors. Liver disease in children. 3rd ed. NewYork: Cambridge University Press;2007. p. 626–652.

3. Roberts EA, Schilsky ML. American Association for Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Diagnosis and treatment of Wilson disease: an update. Hepatology. 2008; 47:2089–2111.

4. Rosencrantz R, Schilsky M. Wilson disease: pathogenesis and clinical considerations in diagnosis and treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2011; 31:245–259.

5. Korman JD, Volenberg I, Balko J, Webster J, Schiodt FV, Squires RH Jr, et al. Screening for Wilson disease in acute liver failure: a comparison of currently available diagnostic tests. Hepatology. 2008; 48:1167–1174.

6. Czaja AJ, Freese DK. American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002; 36:479–497.

7. Lang C, Müller D, Claus D, Druschky KF. Neuropsychological findings in treated Wilson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 1990; 81:75–81.

8. Wolf TL, Kotun J, Meador-Woodruff JH. Plasma copper, iron, ceruloplasmin and ferroxidase activity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006; 86:167–171.

9. Pandey RS, Swamy HS, Sreenivas HS, John CJ. Depression in Wilson's disease. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981; 23:82–85.

10. Sahoo MK, Avasthi A, Sahoo M, Modi M, Biswas P. Psychiatric manifestations of Wilson's disease and treatment with electroconvulsive therapy. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010; 52:66–68.

11. Kumar MK, Kumar V, Singh PK. Wilson's disease with neurological presentation, without hepatic involvement in two siblings. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013; 7:1476–1478.

12. Subrahmanyam DK, Vadivelan M, Giridharan S, Balamurugan N. Wilson's disease-a rare cause of renal tubular acidosis with metabolic bone disease. Indian J Nephrol. 2014; 24:171–174.

13. Fatima J, Karoli R, Jain V. Hypoparathyroidism in a case of Wilson's disease: Rare association of a rare disorder. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 17:361–362.

14. Ferenci P, Caca K, Loudianos G, Mieli-Vergani G, Tanner S, Sternlieb I, et al. Diagnosis and phenotypic classification of Wilson disease. Liver Int. 2003; 23:139–142.

15. Wilson DC, Phillips MJ, Cox DW, Roberts EA. Severe hepatic Wilson's disease in preschool-aged children. J Pediatr. 2000; 137:719–722.

16. Kleine RT, Mendes R, Pugliese R, Miura I, Danesi V, Porta G. Wilson's disease: an analysis of 28 Brazilian children. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012; 67:231–235.

17. El-Karaksy H, Fahmy M, El-Raziky MS, El-Hawary M, El-Sayed R, El-Koofy N, et al. A clinical study of Wilson's disease: The experience of a single Egyptian Paediatric Hepatology Unit. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2011; 12:125–130.

18. Jha SK, Behari M, Ahuja GK. Wilson's disease: clinical and radiological features. J Assoc Physicians India. 1998; 46:602–605.

19. Taly AB, Meenakshi-Sundaram S, Sinha S, Swamy HS, Arunodaya GR. Wilson disease: description of 282 patients evaluated over 3 decades. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007; 86:112–121.

20. Tryambak S, Sumanta L, Radheshyam P, Sutapa G. Clinical profile, prognostic indicators and outcome of Wilson's disease in children: a hospital based study. Trop Gastroenterol. 2009; 30:163–166.

21. Merle U, Schaefer M, Ferenci P, Stremmel W. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and long-term outcome of Wilson's disease: a cohort study. Gut. 2007; 56:115–120.

22. Saito T. An assessment of efficiency in potential screening for Wilson's disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1981; 35:274–280.

23. Medici V, Trevisan CP, D'Incà R, Barollo M, Zancan L, Fagiuoli S, et al. Diagnosis and management of Wilson's disease: results of a single center experience. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006; 40:936–941.

24. Cavanaugh J, Niewoehner CB, Nuttall FQ. Gynecomastia and cirrhosis of the liver. Arch Intern Med. 1990; 150:563–565.

25. Li CP, Lee FY, Hwang SJ, Chang FY, Lin HC, Lu RH, et al. Spider angiomas in patients with liver cirrhosis: role of alcoholism and impaired liver function. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999; 34:520–523.

26. Epstein O, Dick R, Sherlock S. Prospective study of periostitis and finger clubbing in primary biliary cirrhosis and other forms of chronic liver disease. Gut. 1981; 22:203–206.

27. Karnath B. Stigmata of chronic liver disease. Hospital Physician. 2013; 39:14–16.

28. Deguti MM, Tietge UJ, Barbosa ER, Cancado EL. The eye in Wilson's disease: sunflower cataract associated with Kayser-Fleischer ring. J Hepatol. 2002; 37:700.

29. Iorio R, D'Ambrosi M, Marcellini M, Barbera C, Maggiore G, Zancan L, et al. Hepatology Committee of Italian Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition. Serum transaminases in children with Wilson's disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004; 39:331–336.

30. Hellman NE, Gitlin JD. Ceruloplasmin metabolism and function. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002; 22:439–458.

31. Ziakas A, Gavrilidis S, Souliou E, Giannoglou G, Stiliadis I, Karvounis H, et al. Ceruloplasmin is a better predictor of the long-term prognosis compared with fibrinogen, CRP, and IL-6 in patients with severe unstable angina. Angiology. 2009; 60:50–59.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download