This article has been corrected. See "Correction: Clinical Features of Symptomatic Meckel's Diverticulum in Children: Comparison of Scintigraphic and Non-scintigraphic Diagnosis" in Volume 16 on page 135.

Abstract

Purpose

Meckel's diverticulum (MD) has various clinical manifestations, and diagnosis or selectection of proper diagnostic tools is not easy. This study was conducted in order to assess the clinical differences of MD diagnosed by scintigraphic and non-scintigraphic methods and to find the proper diagnostic tools.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review ofthe clinical, surgical, radiologic, and pathologic findings of 34 children with symptomatic MD, who were admitted to Gachon University Gil Medical Center, Inha University Hospital, and The Catholic University of Korea, Incheon St. Mary's Hospital between January 2000 and December 2012. The patients were evaluated according to scintigraphic (12 cases; group 1) and non-scintigraphic (22 cases; group 2) diagnosis.

Results

The male to female ratio was 7.5 : 1. The most frequent chief complaint was lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in group 1 and nonspecific abdominal pain in group 2, respectively. The most frequent pre-operative diagnosis was MD in both groups. Red blood cell (RBC) index was significantly lower in group 1. MD was located at 7 cm to 85 cm from the ileocecal valve. Four patients in group 1 had ectopic gastric tissues causing lower GI bleeding. The most frequent treatment modality was diverticulectomy in group 1 and ileal resection in group 2, respectively.

Conclusion

To diagnose MD might be delayed unless proper diagnostic tools are considered. It is important to understand indications of scintigraphic and non-scintigraphic methods according to clinical and hematologic features of MD. Scintigraphy would be weighed in patients with anemia as well as GI symptoms.

Meckel's diverticulum (MD) is the most frequent congenital malformation of the small intestines due to incomplete degeneration of an omphalomesenteric duct or a vitelline duct, which takes place around 5-7 weeks of the fetal period [1,2]. Complications of the MD have been reported to include hemorrhage, perforation, inflammation, intestinal obstruction, stone formation, and hemia [3]. MD can be diagnosed when symptoms appear due to complications or can be detected accidentally without any symptoms. The former case is often accompanied by hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction and acute abdominal pain [4,5]. Bani-Hani and Shatnawi [6] reported that symptoms occurred more frequently in younger patients, when MD was 2 cm or more in length, when ectopic tissue existed, and in male patients.

There are many methods for diagnosis of MD. Among these, Meckel's scan is an important and non-invasive test with a low radiation burden and it is easy to perform. In particular, it has a high accuracy for detection of MD with ectopic gastric mucosa [7].

Until recently in South Korea, there have been a few reports of clinical study on MD [8,9]. In addition, no study on comparison and analysis of clinical features of MD that are attributable to difference in diagnostic methods has been reported.

Against this background, this study targeted pediatric patients who were diagnosed with symptomatic MD in order to compare and analyze clinical symptoms, examination findings, histological findings, and therapies depending on performance of Meckel's scan. This study is intended to provide useful information for selection of a diagnostic method based on clinical features of patients with MD, and, consequently, for early diagnosis and treatment.

This study targeted 34 patients whose diagnosis of symptomatic MD was confirmed during the period from January 2000 to December 2012 at three university hospitals that located in Incheon city. Regarding the number of patients for each hospital, the Gachon University Gil Medical Center had 14 cases, the Inha University Hospital had 11 cases, and the Incheon St. Mary's Hospital had nine cases. Medical records were examined retrospectively for comparison and analysis of clinical symptoms (gastrointestinal [GI] bleeding, abdominal pain, vomiting, abdominal distension, irritability, etc), complete blood count (CBC) profiles, diagnostic methods, pre-operative diagnoses, operation methods, and pathologic findings after the patients were divided in the group of patients diagnosed by Meckel's scan (group 1) and the group of patients diagnosed using methods other than Meckel's scan (group 2). MD which were accidentally found during other operations, were excluded.

Mann-Whitney test with a MedCalc (MedCalc Software, Acacialaan 22, B-8400 Ostend, Belgium) program was performed for calculation p-value of the CBC profile, and the length and diameter of MD between two groups while p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

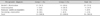

Twelve cases were in group 1 and twenty-two cases were in group 2. According to distribution by sex, 30 cases were male while four cases were female, with a ratio of male to female of 7.5 : 1. The ratio was 5 : 1 in group 1 and 10 : 1 in group 2. Age of the total patients ranged from seven days to 19 years, with 10 cases (29.4%) involving patients aged less than two years, seven cases (20.6%) involving patients aged 2-5 years, nine cases (26.5%) involving patients aged 5-10 years, and eight cases (23.5%) involving patients aged 10 years or older (Table 1).

With respect to major symptoms among the total patients, lower GI bleeding was found in 12 cases (35.3%) while abdominal pain was found in 11 cases (32.4%), which showed 67.7% altogether. Other symptoms included vomiting (three cases, 8.9%), abdominal distension (one case, 2.9%) and irritability (one case, 2.9%). Six patients (17.6%) visited the hospital due to a mass and discharge in the umbilicus (Table 2).

In particular, in group 1, in 11 cases (91.7%), lower GI bleeding was the major symptom, while in group 2, in 10 cases (45.6%), abdominal pain was the most frequent symptom. With respect to clinical features among the total patients, intestinal hemorrhage was found in 16 cases (47.0%), which was the highest number. Other features included intestinal obstruction (12 cases, 35.3%), peritonitis (four cases, 11.8%), and diverticulitis (two cases, 5.9%). Causes of intestinal obstruction included intussusception (five cases, 41.6%), band (three cases, 25%), volvulus (two cases, 16.7%), and invagination (two cases, 16.7%), in this order. Group 1 did not show any clinical feature other than intestinal hemorrhage (Table 3).

Among the total patients, there were 25 cases (73.5%) where an operation was performed due to pre-operative diagnosis or suspicion of MD. And there were nine cases (26.5%) where MD was diagnosed by operation, which included five cases (14.7%) of intussusception that was not cured by air reduction, three cases (8.9%) of omphalitis, and one case (2.9%) of neonatal enterocolitis. In group 1, 91.7% of patients (11 cases) were estimated to have MD prior to the operation, while there was one case where ultrasonogram confirmed the intussusception which was not cured by air reduction. In group 2, only 63.6% of patients (14 cases) were estimated to have MD before the operation was performed (Table 4).

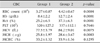

According to the results of a blood test performed on the day the patients were admitted to the hospital, statistically significant differences in values of red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) were observed between group 1 and group 2 (Table 5). In regard to platelet count, no statistical difference was observed between two groups. Interestingly, one patient in group 1 had accompanying idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (Table 5).

Exprolo-laparotomy (42.4%) was one of the most frequently used examinations for determining the cause of disease before diagnosis. Meckel's scan was performed for 12 cases (36.4%), followed by abdominal CT (15.2%), ultrasonogram (12.1%), colonoscopy (12.1%), and GI bleeding scan (6.1%), in this order (Table 6). In five cases out of 12 cases where Meckel's scan was performed, H2 blocker was injected prior to scanning. In one case, the result was false negative initially, whereas it was positive on the second scan.

Among a total of 34 patients, partial resection of the small intestine was performed for 16 cases (47.0%), while diverticulectomy was performed for 14 cases (41.2%). With respect to complications, pneumonia was found in one case where partial resection of the small intestine was performed, while hepatitis was found in one case where diverticulectomy was performed. However, the complications were completely cured by proper treatments. In addition, mass excision was performed in four cases (11.8%) as incision of the umbilical area was performed. Diverticulectomy was performed for 66.7% of cases in group 1, while partial resection of the small intestine was performed for 54.5% of cases in group 2, which showed a difference in surgical method between the two groups (Table 7).

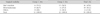

Mean distance of the diverticulum from the ileocecal valve was 52.4 cm in group 1 and 42.9 cm in group 2. Mean length of the diverticulum was 3.6 cm and 3.8 cm, respectively, while the mean diameter of the diverticulum was 1.8 cm and 1.7 cm, respectively (Table 8).

From a total of 34 patients, three cases where pathological findings were not available were excluded, therefore, ectopic tissue was found in 11 cases (35.5%) out of 31 cases. Small intestine mucosa tissue was found in 18 cases (58.1%), gastric mucosa tissue was found in eight cases (25.8%), and both gastric and pancreatic mucosa tissue were found in three cases (9.7%). In addition, the remaining omphalomesenteric duct was found in two cases (6.4%). In both group 1 and group 2, small intestine mucosa was found in the highest number of cases. On the contrary, group 1 and group 2 showed ectopic mucosa in six cases (50%) and five cases (26.3%) respectively, which demonstrated that the percentage of ectopic mucosa was relatively higher in group 1 (Table 8). In addition, lower GI hemorrhage was found in five cases (45.5%) out of 11 cases in total where gastric mucosa tissue was found.

In the initial fetal period, the vitelline duct connects the yolk sac with the midgut. The vitelline duct shrinks and becomes closed within 7-8 weeks when the yolk sac is replaced by the placenta as a source of nutrition for the fetus. In this case, if the vitelline duct remains, this may cause MD, intestinal umbilical fistula, vitelline cyst, fibrous cord, or intestinal umbilical sinus depending on the degree of closure. Among these, MD is the most common [10].

Incidence rate of MD is 2-3%. In most cases, MD shows no symptoms but causes complications such as hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction, inflammation, and perforation in less than 5% of cases [11].

In regard to incidence rate based on sex ratio, more male than female were reported to have MD at a ratio of 2.4 : 1 in the study for adults and children by Yamaguchi et al. [12], and a ratio of 2.3 : 1 in the study for only children by Lee et al. [8]. In this study, which targeted only children, the ratio was 7.5 : 1, the results were weighted towards male. However, Mackey and Dineen [13] reported that no difference in sex ratio was found when MD showed no symptoms (when MD was found accidentally in the middle of an autopsy). They reported that incidence rate of complications was higher by 3-4 times in male than in female. With respect to incidence frequency by age, Lee et al. [14] stated that MD was found in 60% of patients aged 6 years or younger. Lee et al. [9] also stated that patients in the less than 5 years showed the highest frequency of incidence. In this study that targeted children, patients younger than 10 years took up 66.5% of the total patients.

Depending on complications, clinical symptoms include lower GI hemorrhage, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Among these systems, abdominal pain is the most common. However, this study found that indolent lower GI hemorrhage was the most common symptom. Regarding complications among adults and children, Mackey and Dineen [13] reported intestinal obstruction of 33.8%, inflammation of 30.9%, and rectal hemorrhage of 25%. In the study for only children by Lee et al. [9] reported that the GI bleeding was the most frequent (76%). In addition, in this study, lower GI bleeding (47.0%) was the most common, followed by intestinal obstruction (32.4%), which showed the second highest percentage. In particular, the main symptom of lower GI bleeding was found in 91.7% of cases in group 1, where Meckel's scan was performed. In group 2, where Meckel's scan was not performed, abdominal pain was the most common, as it was found in 45.6% of cases in the group. Group 1 did not show any clinical features other than GI bleeding. Regarding pre-operative diagnosis, Yamaguchi et al. [12] reported intestinal obstruction of 42.5%, acute appendicitis 24.7%, and MD 11.8%. In this study, however, in 73.5% of cases, an operation was performed due to diagnosis with or suspicion of MD, which was the highest percentage, followed by intussusceptions that were not cured by air reduction at 14.7%, omphalitis at 8.9%, and neonatal enterocolitis at 2.9%.

Lower GI bleeding is a major symptom of MD. Amount of bleeding may vary in diverse cases, ranging from a positive reaction to stool occult blood test to active massive bleeding that leads to failure in circulatory function. In particular, if the case is the latter one (massive bleeding) or continuous bleeding (even though the amount is small), this causes anemia due to loss of blood [15,16]. In this study, group 1 showed statistically significant differences in values of RBC count, Hb, Hct, MCV, and MCH, greater than those of group 2. Platelet count showed that one patient in group 1 had idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Consequently, if a patient who visits the hospital due to lower GI bleeding, abdominal distension, or abdominal pain shows severe anemia or unexplained anemia, it is desirable to perform Meckel's scan in consideration of the possibility of MD as the first priority.

For diagnosis of MD, Meckel's scan (99mTc-pertechnetate) is mainly performed, as an isotope is used to find ectopic gastric mucosa. This is the best non-invasive method for pre-operative diagnosis of MD with ectopic gastric mucosa, which is used for patients with lower GI hemorrhage. Among children, detection rate using Meckel's scan was reported to be 90% [17], while sensitivity and specificity were reported to be 0.6-0.75, positive predictive value 1.0, and negative predictive value 0.77 [15]. Using Meckel's scan, non-specific false positive findings are not common while potential causes include intestinal obstructive disease, intussusception, inflammatory disease, arteriovenous malformation, ulcer, GI tumor, angioma, and anomaly of the urinary system (hydronephrosis, ectopic kidney, vesicoureteral reflex, and bladder diverticulum). False negative diagnosis is attributable to the case where ulcer and hemorrhage are found without ectopic gastric mucosa, the case where ectopic gastric mucosa is insufficient or its function is insufficient according to reading of a scanned image (abnormality in blood supply), the case where radioactivity is diluted or washed away due to hemorrhage or intestinal hypersecretion, or the case where increased echogenisity is concealed due to lack of skill or duplication of organs (bladder or duodenum) [18]. Pentagastrin, glucagon, and H2 blocker are injected in order to increase sensitivity of Meckel's scan. Cimetidine, a commonly used antagonist of histamine receptor (H2), suppresses secretion of pertechnetate inside the intestine. Intravenous injection of cimetidine one hour before isotope scan can increase accuracy of diagnosis [19]. In this study, premedication was administered only for 41.7% of patients in the group where Meckel's scan was performed. One case was shown to be a false negative on the first scan, whereas it was positive on the second scan.

When a child with lower GI bleeding, the cause of which is not known, does not show any indication or ectopic gastric mucosa, Meckel's scan is negative. Therefore, many methods, including high-resolution ultrasound scan, laparoscopy, and CT have been tried for diagnosis of MD at an early stage [20]. In this study, Meckel's scan was performed for 36.4% of patients, while diagnostic laparoscopy was performed for 42.4% of patients, as was the most used diagnostic method.

Treatment of MD with symptoms is surgical resection. State of lesions and anatomical differences must be considered before a proper operation method is chosen, such as diverticulectomy or end-to-end anastomosis after ileal resection. Ileal resection is performed for a patient with hemorrhage who has a broad-based diverticulum in order to avoid a situation in which ectopic mucosa remains after surgery. However, Piñero et al. [20] reported that ileal resection showed a higher frequency of post-operative complications, such as infection or intestinal obstruction (stenosis or band) in junction than diverticulectomy. In particular, if the diameter of the diverticulum base is larger than that of the intestine, a child is likely to have stenosis of the ileum after diverticulectomy. Therefore, ileal resection has been known to be safer [10]. In this study, the numbers of diverticulectomy and of ileal resection were almost similar, whereas a simple diverticulectomy took up the higher percentage in group 1.

According to Yamaguchi et al. [12] ectopic tissue in MD was found together with gastric mucosa (62.4%), pancreatic tissue (16.1%) or small intestine mucosa (2.1%). According to Lee et al. [9] tissue was found along with small intestine mucosa (43%), gastric mucosa (48%), or both gastric and pancreatic mucosa (9%), while there was no case of pancreatic mucosa alone. In this study, however, ectopic tissue was found along with small intestine mucosa tissue (58.1%), gastric mucosa tissue (25.8%), or both gastric and pancreatic tissue (9.7%). Out of the 11 cases where gastric mucosa tissue was found, five cases (45.5%) showed lower GI bleeding. Reason for the GI bleeding is that as around 80% of MD mucosa is attributable to gastric mucosa, gastric acid is secreted in ectopic gastric mucosa inside diverticulum, causing damage to the intestine. However, gastric mucosa tissue was found only in 50% of cases in group 1.

Yahchouchy et al. [21] reported that as the length of the diverticulum and diameter of its base were factors causing complications of MD, a narrow-and-long-based diverticulum was more likely to cause intestinal obstruction and inflammation, whereas foreign bodies were likely to slide into a broad-and-short-based diverticulum. According to the report by Lee et al. [8], diverticulum was located primarily in the distance of 35-70 cm in the proximal part from the ileocecal valve, and the length of the diverticulum was less than 5 cm in 80% of cases. Lee et al. [9] also reported that diverticulum was located at a mean distance of 45.9 cm from the ileocecal valve, while the mean length of the diverticulum was 3.2 cm with a mean diameter of 1.8 cm. In addition, in this study, diverticulum was located at a mean distance of 47.0 cm (7-85 cm) toward the proximal part from the ileocecal valve, while the mean length of the diverticulum was 3.7 cm (1.5-7 cm) with a mean diameter of 1.8 cm (1-7 cm).

In this study, which was conducted retrospectively, there were some limitations, namely that negative scan data and insufficient premedication cases for the scan were excluded. Finding clinical features and hematological characteristics for selection of diagnostic methods including Meckel's scan is essential, because a quick and accurate diagnosis is important in order to minimize complications that may be caused by late diagnosis of MD and to ensure a quick recovery. It is desirable to perform Meckel's scan in consideration of the possibility of MD as the first priority if patients suffer from GI bleeding or unexplained anemia as well as GI symptoms.

It is believed that prospective studies on comparison of scintigraphic and non-scintigraphic diagnosis of MD are required henceforward.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Shandling B. Walker WA, Durie PR, Hamilton JR, Walker-Smith JA, Watkins JB, editors. Diverticular disease. Pediatric gastointestinal disease. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. 1996. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby;919–921.

2. Blevrakis E, Partalis N, Seremeti C, Sakellaris G. Meckel's diverticulum in paediatric practice on Crete (Greece): a 10-year review. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2011. 8:279–282.

3. Fa-Si-Oen PR, Roumen RM, Croiset van Uchelen FA. Complications and management of Meckel's diverticulum--a review. Eur J Surg. 1999. 165:674–678.

4. Menezes M, Tareen F, Saeed A, Khan N, Puri P. Symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum in children: a 16-year review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008. 24:575–577.

5. Lüdtke FE, Mende V, Köhler H, Lepsien G. Incidence and frequency or complications and management of Meckel's diverticulum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989. 169:537–542.

6. Bani-Hani KE, Shatnawi NJ. Meckel's diverticulum: comparison of incidental and symptomatic cases. World J Surg. 2004. 28:917–920.

7. Sinha CK, Pallewatte A, Easty M, De Coppi P, Pierro A, Misra D, et al. Meckel's scan in children: a review of 183 cases referred to two paediatric surgery specialist centres over 18 years. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013. [Epub ahead of print].

8. Lee JB, Lee YS, Yoo ES, Kim HS, Son SJ, Park EA, et al. A clinical manifestation of Meckel's diverticulum. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 2002. 45:466–472.

9. Lee YA, Seo JH, Youn HS, Lee GH, Kim JY, Choi GH, et al. Clinical features of symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006. 9:193–199.

10. Weinstein EC, Cain JC, Remine WH. Meckel's diverticulum: 55 years of clinical and surgical experience. JAMA. 1962. 182:251–253.

11. Kusumoto H, Yoshida M, Takahashi I, Anai H, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K. Complications and diagnosis of Meckel's diverticulum in 776 patients. Am J Surg. 1992. 164:382–383.

12. Yamaguchi M, Takeuchi S, Awazu S. Meckel's diverticulum. Investigation of 600 patients in Japanese literature. Am J Surg. 1978. 136:247–249.

13. Mackey WC, Dineen P. A fifty year experience with Meckel's diverticulum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1983. 156:56–64.

14. Lee KH, Yeung CK, Tam YH, Ng WT, Yip KF. Laparascopy for definitive diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2000. 35:1291–1293.

15. Al-Onaizi I, Al-Awadi F, Al-Dawood AL. Iron deficiency anaemia: an unusual complication of Meckel's diverticulum. Med Princ Pract. 2002. 11:214–217.

16. Esposito C, Giurin I, Savanelli A, Iaquinto M, Ascione G, Settimi A. Meckel's diverticulum causing severe hemorrhage. Eur J Pediatr. 2012. 171:733–734.

17. Soltero MJ, Bill AH. The natural history of Meckel's Diverticulum and its relation to incidental removal. A study of 202 cases of diseased Meckel's Diverticulum found in King County, Washington, over a fifteen year period. Am J Surg. 1976. 132:168–173.

18. Ford PV, Bartold SP, Fink-Bennett DM, Jolles PR, Lull RJ, Maurer AH, et al. Procedure guideline for gastrointestinal bleeding and Meckel's diverticulum scintigraphy. Society of Nuclear Medicine. J Nucl Med. 1999. 40:1226–1232.

19. Sohn MH, Han YM, Kim JS, Choi KC. Scintigraphic detection of Meckel's diverticulum. Chonbuk Univ Med J. 1990. 14:99–105.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download