Abstract

Purpose

To estimate the prevalence of dietary supplement (DS) use, investigate the related factors associated with DS use among preschoolers and support the adequate nutrition.

Methods

We conducted a questionnaire survey of mothers of children aged between 1 and 6 years who visited pediatric clinics in 3 Korean cities (Jeonju, Suncheon, Jeongeup) between October and November 2012 at Presbyterian Medical Center. The responses from 929 questionnaires were analyzed.

Results

Approximately 45.1% of the preschoolers used DS in the past month. The following factors were associated with greater use of DS: older age (p<0.001), whether or not the preschoolers attended kindergarten (p<0.001), higher mother's concern about the nutritional facts (p<0.001), whether or not the mother use DS (p<0.001), whether or not the mother counsel with a doctor or pharmacist about DS use (p<0.001). Vitamin·mineral supplements (77.5%) were the most commonly used DS among the preschoolers, followed by ginseng (49.3%) and probiotics (25.6%). Additionally, of the DS users, 95.9% gave DS to their healthy children. Of the users and non-users, 97.6% and 62.2%, respectively, indicated that they would like to have their children take DS. The information on DS was obtained from family or friends in 48.2% of the DS users and from doctors in only 6.1%.

Go to :

The cases of adding raw materials with efficient functions on the human body and insufficient nutrients as the social interest in the health and well-being increases [1] and the dependency on the dietary supplement has grown for the health of family members due to inflating worries about the health from increasing number of dual incomes and Westernized diet [2]. In addition, the interest in the children health grows due to social changes including increasing income of parents, growing academic achievement among parents and lowering birth rates, shifting the trend in purchasing functional products for adults to those for children and adolescents [3]. A recent Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) showed that 33.8% of Koreans took dietary supplements for the last year and the group of aged 3-5 years accounted for 48.6%, followed by 1-2 years old for 39.1% [4].

The preschool age is the period when all the organs show the fastest growth and development, proper nutrition is very crucial and the dietary habits formed in this period affects the health for the life. In addition, improper nutrition supply may cause various chronic diseases [5,6]. It is very important to form a right dietary habit in the preschool age. However, the portion of the nutrition education by specialists including pediatricians is very limited. Even worse, improper nutrition supply and dietary supplement abuse are concerned because parents rely on laymen including their friends or acquaintances [7].

Surveys on the dietary supplement intake have been reported in various fields with growing dietary supplement intake rates. And yet, the studies on the intake status and factor analysis for the preschoolers with highest intake rates are scarce. Therefore, the purpose of the study is to help guide preschoolers to right nutrition intake by understanding factors and trend in the dietary supplement intake in 3 Korean cities.

Go to :

The study performed a survey on the mothers of preschoolers (1-6 years old) who visited pediatricians in 5 primary and secondary clinics in 3 cities of Korea (Jeonju, Suncheon, Jeongeup) from September to November, 2012 at Presbyterian Medical Center. The study covered the subjects who agreed filling in the questionnaires, collected 935 out of 1,000 questionnaires (appendix) (93.5% of retrieval) and analyzed 929 questionnaires (92.9%) except the questionnaires with insufficient answers.

The study defined the dietary supplement as (non-) pharmaceutical and food products with the purpose of supplementing efficient and functional elements or taking nutrition including health functional food [8] and the dietary supplement intake considers the case regularly taking the supplements for more than one month in the recent one year. The questionnaire contained questions on general features, society- and health-related factors, dietary habits and trend in the dietary supplement intake of the subjects. The general features included the gender, age, birth order, height, weight of the children and ages, academic background, occupation and monthly average income of the parents. The societyand health-related issues included visiting daycare centers, chronic diseases, number of visiting clinics or hospitalization, number of medical checkups for infants and toddlers, interests in the child health of the mother, health status of the child from the mother's viewpoint, checking the nutrition label and knowledge when buying processed food, dietary supplement intake among family members and counseling with doctors or pharmacists on the dietary supplements. The knowledge on the nutrition by the mothers was evaluated by the 10 out of 28 questions on the nutrition by Min [9] based on the 5 major nutrients with point 1 for correct and 0 for wrong answers. The questions on the dietary habits consisted of regularity on the meals, amount, pace, pickiness, frequencies in taking snacks and dining out and hours of watching TV or using computer and the trend in the nutrition supplement intake covered kinds of the dietary supplements, period, type, frequency, major information sources, reason and future plans.

The statistical analysis was performed on the survey data by the t-test with independent samples and the cross analysis (chi-square test) using the IBM SPSS Statistics program (version 21.0; IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) and considered p<0.05 as significant data. The logistics regression analysis or the multivariable analysis was performed with significant variables from the univariable analysis to understand the impact on the intake.

Go to :

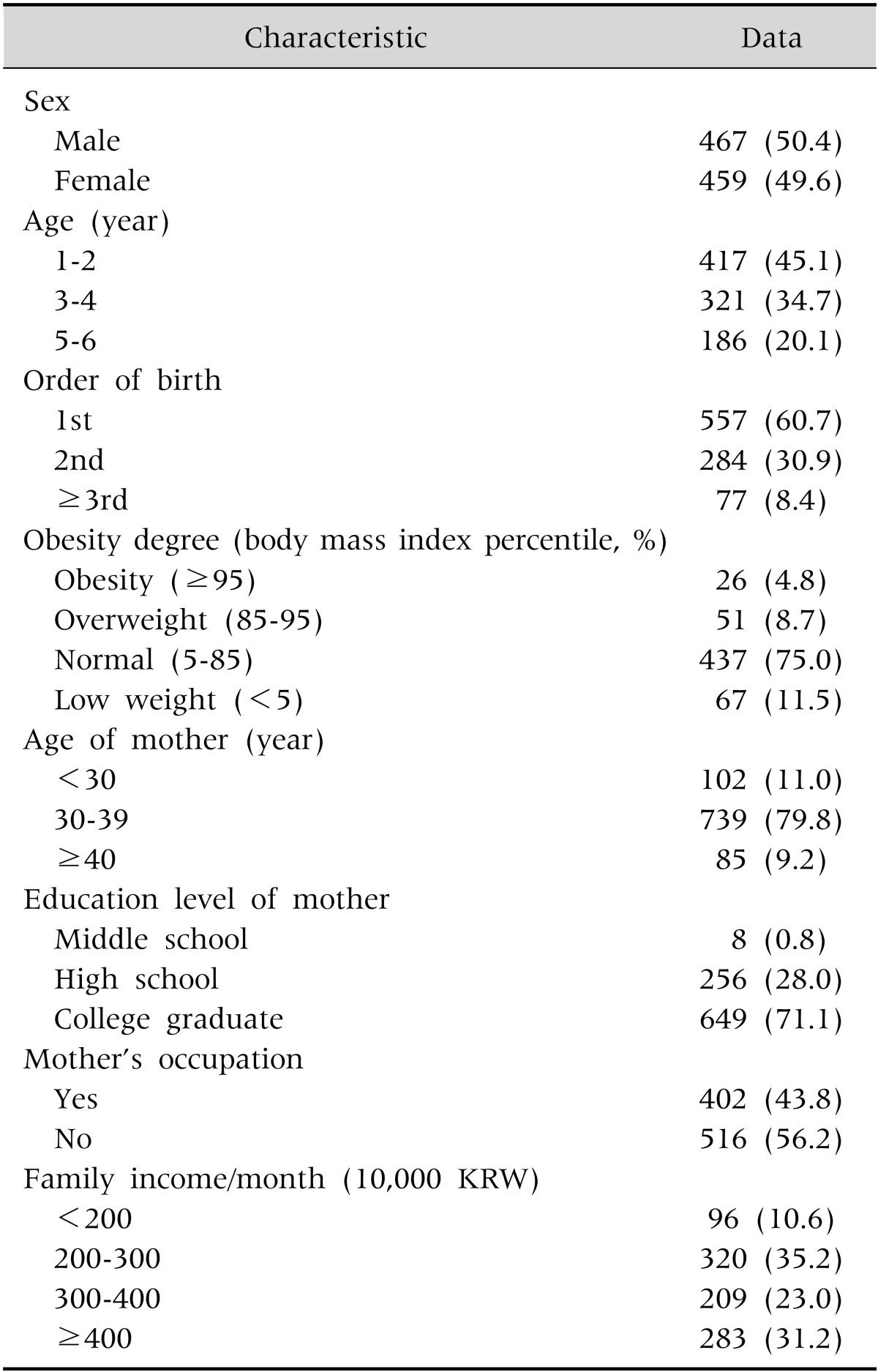

The number of preschoolers in the study was 926 including 467 (50.4%) boys and 459 girls (49.6%) (Table 1). The mean age of the children was 3.4±1.57 years old and the birth order showed that 557 (60.7%) children were the eldest and 284 were the second (30.9%), meaning that 91.6% of the children were the eldest or second eldest. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the heights and weights of the children answered by their parents and the indexes showed that 67 children (11.5%) were underweight, 437 (75.0%) were normal weight, 51 (8.7%) were overweight and 26 (4.8%) were obese based on the categorization of the underweight with less than 5%, normal weight with 5-84%, overweight with 85-94% and obese over 95% of the indexes. The number of children visiting daycare centers was 764 (85.0%) and their mean age starting the visit was 1.87±1.10 years old. The data showed that the mean age of the parents was 30s for 649 fathers (70.3%) and 739 mothers (79.8%), academic background was higher than university graduates for 678 fathers (73.9%) and 649 mothers (71.1%) and 516 mothers (56.2%) were housewives.

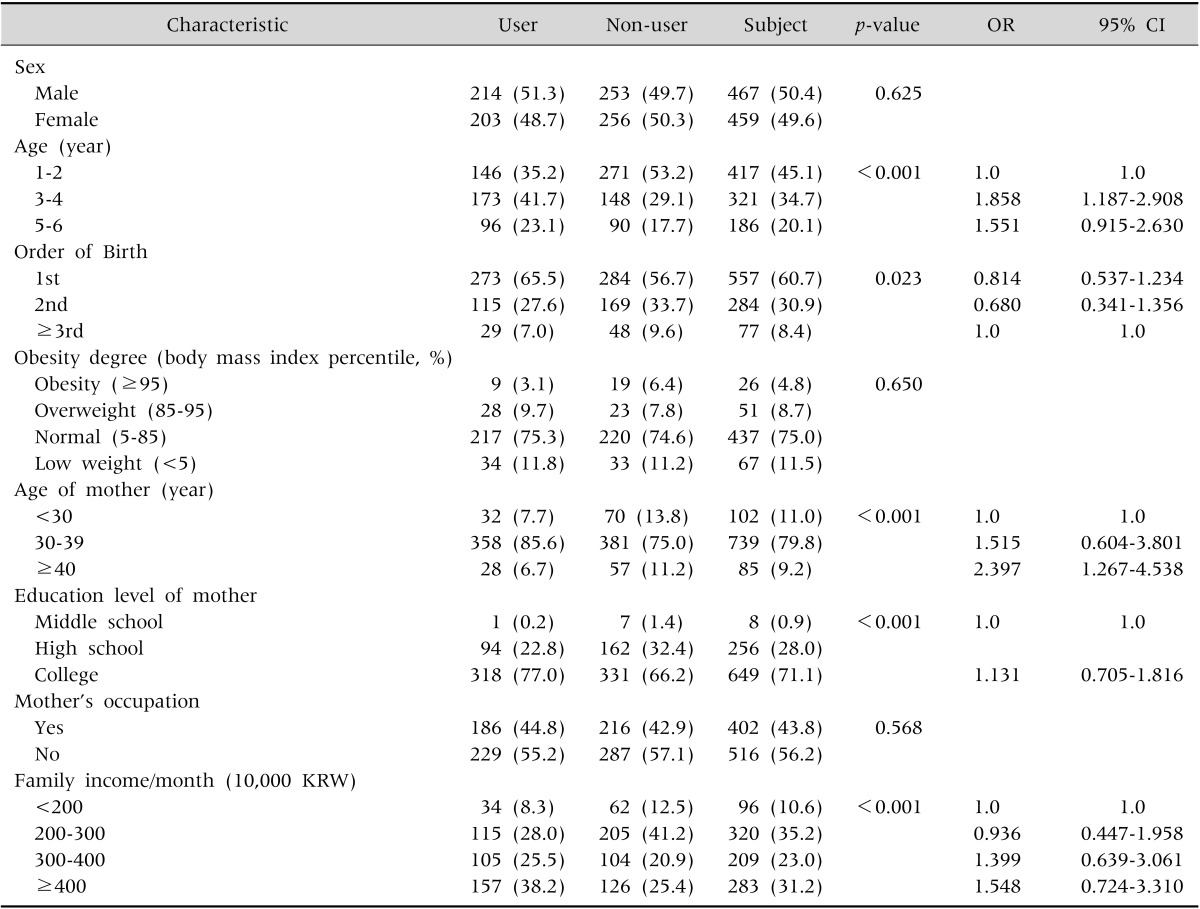

It was discovered that 419 out of 929 preschoolers (45.1%) in the study regularly took dietary supplements longer than a month for a recent year. The dietary supplement intake rates were significantly high for older children (p<0.001) and mothers older than 40s, rather than less than 30s (p<0.001) (Table 2). No significance in the dietary supplement intake was found in the gender, birth order, BMI of the children, age of fathers, academic background and occupations of the parents and family income.

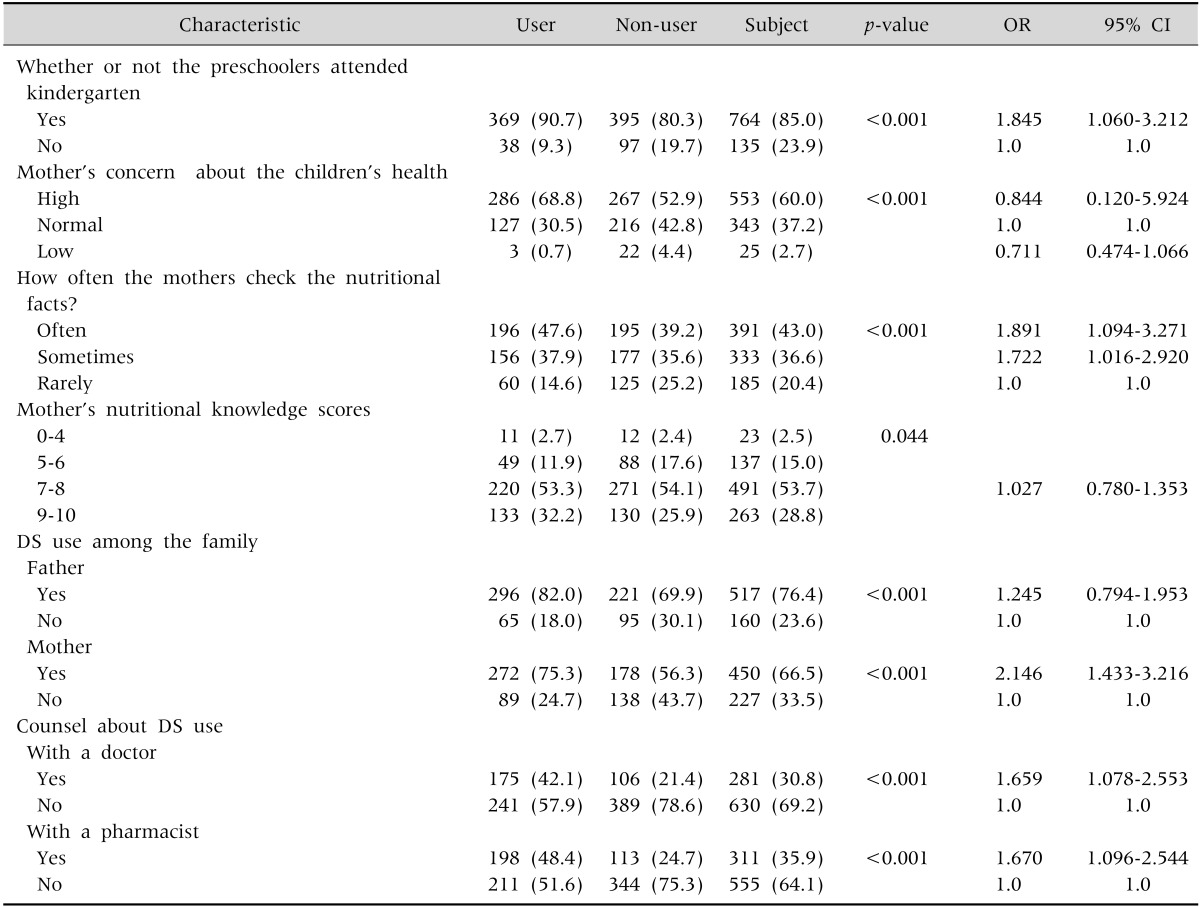

It was found out that the children in the daycare centers (p<0.001) and the mothers who frequently checked the nutrient label in purchasing processed food (p<0.001) and took dietary supplements (p<0.001) showed significantly higher dietary supplement intake rates for the children than their counterpart and the rates of consulting the dietary supplement intake with doctors or pharmacists were significantly higher in the intake group than its counterpart (p<0.001) (Table 3). The factors including interest and knowledge of mothers on the health of their children, health status of the children from their mothers' viewpoint, dietary supplement intake of fathers or siblings, chronic diseases of children, the number of visiting clinics or hospitalization and medical checkups for infants and toddlers showed no significance in the dietary supplement intake.

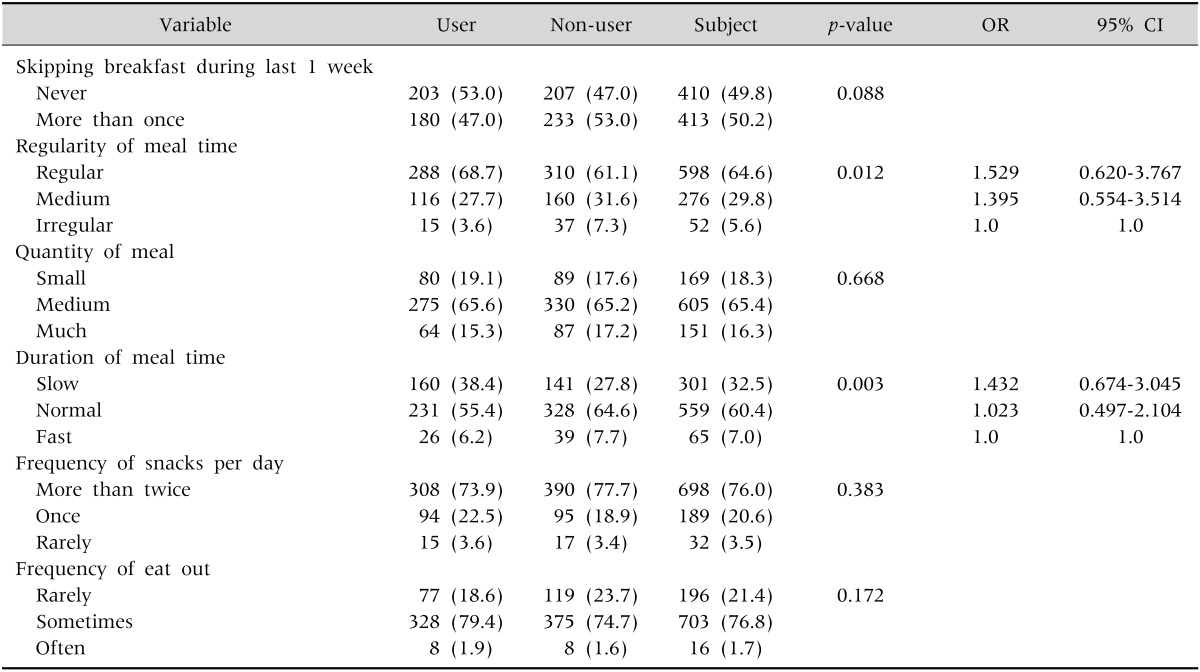

The dietary habits including the regularity of meals for children, amount, the rates of morning without meals, the number of taking snacks, watching TV and using computer did not show significant relations to the dietary supplement intake for the children (Table 4).

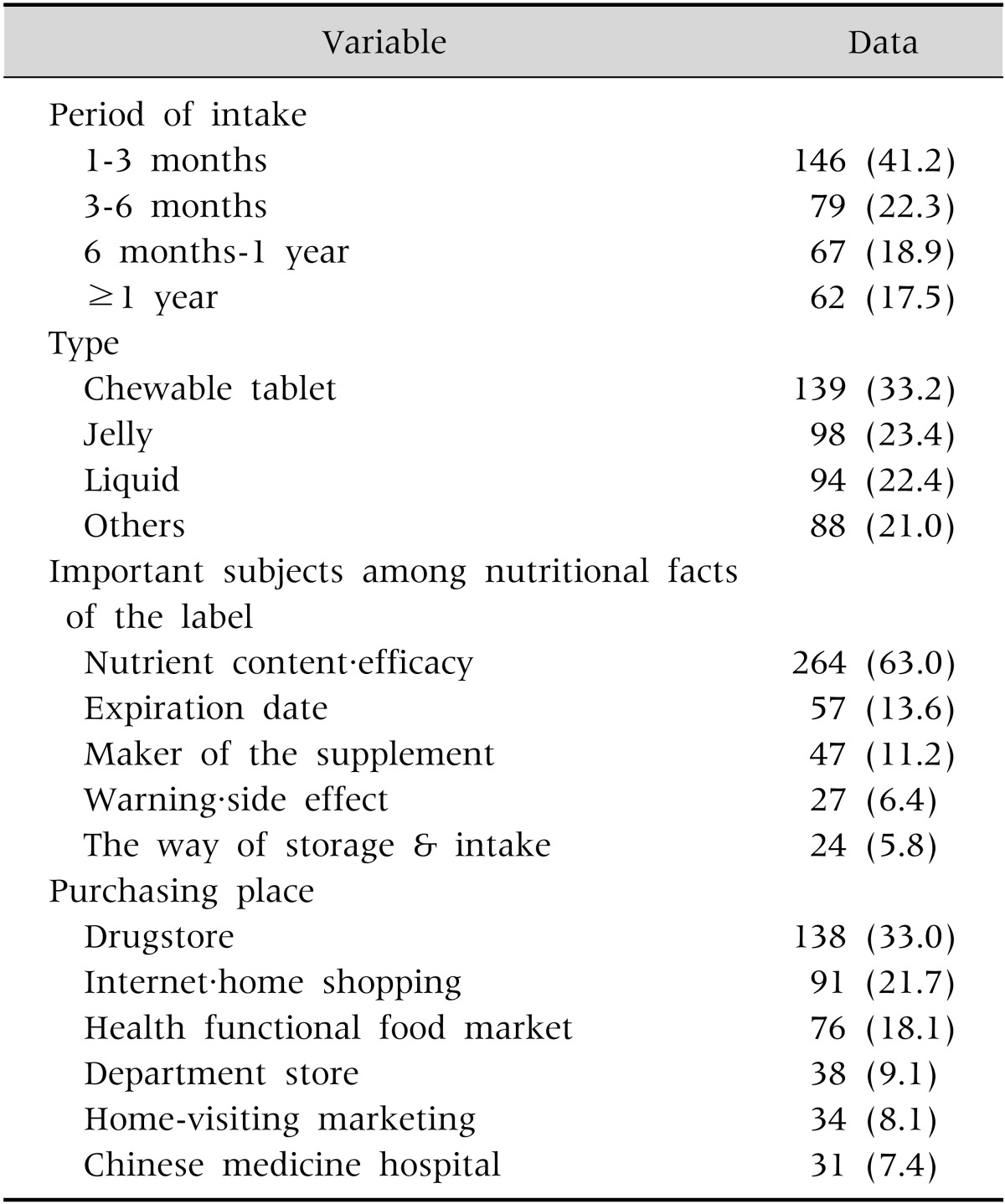

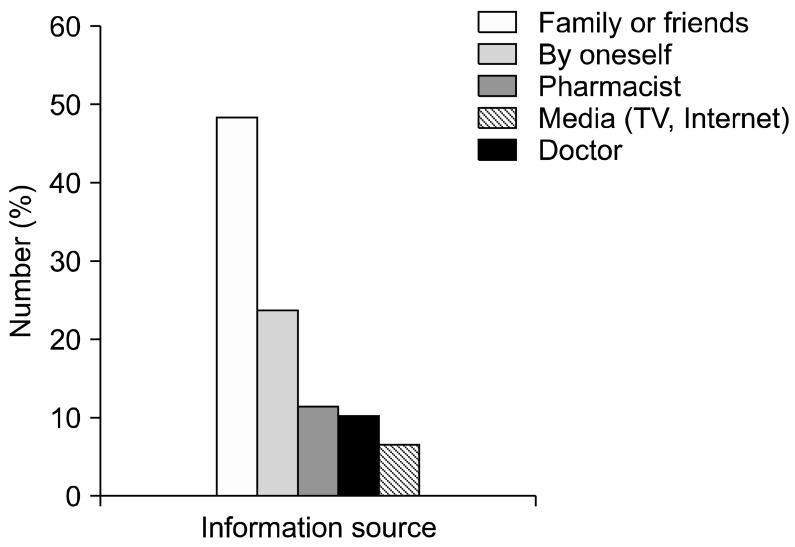

The mean kinds of dietary supplements taken by the preschoolers was 1.9±0.13 and 2 showed the highest portion of 187 (45.5%), followed by 1 for 145 (35.3%) and more than 3 for 80 (19.5%) children. The survey which allowed multiple answers on the kinds of dietary supplement intake showed that 321 children (77.5%) took vitamins and minerals, followed by 204 children (49.3%) for red ginseng, ginseng and Oriental medicines, 106 (25.6%) children for yogurt tonics and medicines for intestinal disorders, 35 children (8.5%) for colostrum tonics, 33 children (8.0%) for tonics for height growth and 27 children (6.5%) for omega (Fig. 1). The period of continuously taking dietary supplements showed that 146 children (41.2%) took between 1 and 3 months, followed by 79 children (22.3%) between 3 and 6 months, 67 children (18.9%) between 6 months and 1 year and 62 children (17.5%) for longer than 1 year. In addition, the types of the dietary supplements mainly taken by the children showed that 139 children (33.2%) enjoyed chewable type, followed by jellies for 98 children (23.4%) and liquid for 94 children (22.4%) (Table 5). The frequencies showed that 248 children (59.4%) took once a day, 153 children (36.7%) took 2-3 times a day and 16 children (3.9%) took less than once a day. In addition, 227 children (67.1%) showed the largest portion in regularly taking the supplements under healthy condition, followed by 119 children (28.8%) irregularly took when healthy and 17 children (4.1%) took when ill. The health difference before and after the intake shows that 195 children (46.5%) answered 'no specific changes', followed by 'decreasing the frequencies in illness' for 84 children (20.1%) and 'increasing the appetite' for 80 children (19.1%). In the aspect of checking nutrition labels on the dietary supplements, 244 mothers (58.4%) answered they checked the labels well 264 mothers (63.0%) answered they mattered efficacies and nutrients contents, followed by cautions harmful side effects for 27 mothers (6.4%) and storage and instruction for 24 mothers (5.8%). The largest number of mothers, 237 (58.7%) answered they checked the nutrient labels to achieve efficacies and nutritional information, followed by stability for 100 mothers (24.8%) and harmful side effects for 5 mothers (1.2%) on the question of why the mothers checked the nutrient labels. The sources of the dietary supplement information consisted of acquaintances including family members or friends for 198 mothers (48.2%), followed by self-judgment for 96 mothers (23.4%), recommendation from pharmacists for 46 mothers (11.2%), the Internet and TV for 40 mothers (9.8%) and recommendation from doctors for 25 mothers (6.1%) and the results of purchasing venues were pharmacies for 138 mothers (33.0%), the Internet and home shopping sites for 91 mothers (21.7%), functional food shops for 76 mothers (18.1%), department stores and malls for 38 mothers (9%), mail orders for 34 mothers (8.2%) and Oriental clinics for 31 mothers (7.5%). The reason why mothers gave dietary supplements to their children are to 'help growth and nurturing for their children' (133 mothers or 31.7%), 'upgrade health' (130 mothers or 31%), 'supplement insufficient nutrients' (80 mothers or 19.1%) and 404 mothers (98.8%) of the subject group and 314 mothers (62.2%) of the control group answered that they 'have plans to give dietary supplements to their children'.

Go to :

Approximately half of the preschoolers in our study used dietary supplement, which might not have been medically indicated for most of them. Dietary supplements are categorized as a kind of health functional foods, used for all the age groups from infants to the elderly people. Korean infants and toddlers have been found to be given various dietary supplement products, including vitamins and minerals, supplementary medicines for intestinal disorders, colostrum, growth supplements and ginseng products [10]. Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (KFDA) reported that 5,000 kinds of licensed dietary supplements are available in the market, many of which have been the cause of concerns because lack of verification [11]. The KNHANES discovered that 48.7% of children aged between 1 and 3 years were given dietary supplements, with vitamins and minerals accounting for the largest portion of 35.3% [4]. In the past, people concentrated on taking the minimum supplement dose owing to insufficient vitamin and mineral intakes, the supplementary nutrients were beneficial and caused no problems even in high doses. However, excessive nutrient intake was reported to possibly harm the human body. Accordingly, nutritional authorities categorized and managed vitamin and mineral products based on the risk level associated with each nutrient by establishing the minimum and maximum doses, guidelines for the proper intake of these products, which enforce awareness and promote overdose prevention [12].

A previous study reported that the dietary supplement intake rates among preschoolers was 45.1%, higher than the 32% among adults [13] and 39% among American children aged between 1 and 8 years. In addition, the dietary supplement intake rates significantly rose with older ages of the preschoolers, indicating similar results from previous studies [10,14,15]. The dietary supplement intake rates of the Korean preschoolers aged between 2 and 6 years was 46% [15], lower than the 50.9% of their counterparts in Germany aged between 2 and 4 years [16] but, higher than the 30% American children aged between 2 and 8 years [14,17,18]. Preschool age is the period that greatly affects lifetime health, and during which exercise ability develops and major organs and tissues massively grow. However, children during thise period are highly sensitive to infectious diseases owing to the immune system being not yet fully developed and exposure to various accidents and diseases. The purpose of dietary supplements is to prevent diseases such colds, improve cognitive functions, stimulate growth, compensate for irregular dietary habits and enhance the appetite of children [19].

The mean number of children in a Korean family was 1.23 in 2010 because of the gradual decrease in the population, small number of marriages, and older age at pregnancy. Among Korean children, 50.4% are the eldest and 38.9% are the second eldest, comprising 90% of the total children population [20]. The mean number of children in the study was 1.94±0.71, with 60.7% and 30.9% birth orders for the eldest and second eldest children, similar to those reported in the previous study. The authors considered the eldest children to have a high amount of dietary supplement intake, but the study showed no significant difference between the birth order and the dietary supplement intake. Dietary supplement intake rates were previously reported to be low among boys [21] and girls [22], indicating not significant difference between sexes [15] and between dietary supplement intake rates and both sexes. Previous studies showed significantly high dietary supplement intake rates for children with normal weights or chronic disease [15], or low weights [14,17]. However, the study showed no significant difference in dietary supplement intake rates between BMIs and chronic diseases of the children. In addition, Shaikh et al. [17] reported that the children who frequently visited clinics showed high dietary supplement intake rates but that hospitalization, clinic visits and medical checkups for infants and toddlers had no significant relationship with the dietary supplement intake rates, implying that the diseases or clinic visits of the children did not affect the dietary supplement intake much.

A study of the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs in 2011 reported that the rates of children who visited daycare centers was 68.0%, increasing on a yearly basis, and that the rates of visiting daycare centers according to age were 54.1% of infants and 82.0% of toddlers [23]. The rates of children who visited daycare centers in the study was 85%, and the mean age of the children who started visiting the centers was 1.87±1.10 years. The number of children who took dietary supplements was significantly higher and that of children who visited daycare centers was significantly higher than that of children not taking dietary supplements. This demonstrates that the children in daycare centers took more dietary supplements because the children were thought to have fewer snacks or meal intakes at home and insufficient nutritional intake. However, children in daycare centers take in snacks twice a day and a meal once a day at least. In addition, approximately 45% of the daily recommended allowance was reported to be supplied from daycare centers [24], suggesting that the meals and snacks in the daycare facilities should be considered to provide nutrition to the children.

Furthermore, the study demonstrated that the dietary supplement intake rates of the preschoolers were the same with those in the previous studies [8,21] in that the rates had no significant relationship with the occupations of the mothers, suggesting that double-income families did not increase the dietary supplement intake of their children. In addition, the dietary supplement intake rates of the children were significantly higher when their mothers took dietary supplements but showed no relation to the intakes of fathers, siblings, grandparents and family relatives. This finding is similar to the study of Song and Kim [21], with mothers having the most effects. The study indicated that the dietary supplement intake rates of the children were significantly high because the mothers checked the nutrient labels on processed food more often, which indicates the importance they give to the right consciousness and knowledge of the nutrition for their children.

No clear standards of dietary supplement intake have been established thus far. However, dietary supplement intake among children is recommended if they show sluggish growth, fail to take daily recommended nutrients, only have vegetables, are raised in broken families, are abused, have chronic diseases, show continuous loss of appetite or fail to take proper food, suggesting that infants and toddlers with a healthy diet do not need to take vitamin or mineral supplements [11,25]. Yoon et al. [15] stated that the dietary supplement intake of children increased as they did not skip meals, took in good snacks, and kept healthy dietary habits. Picciano et al. [14] reported that the dietary supplement intake significantly increased as the children watched TV or used computers less. Moreover, Shaikh et al. [17] demonstrated that children took more dietary supplements as they engaged in more physical activities and had healthy food. The study showed no significant relation between dietary habits, including regularity, pace, and amount of meals; rates of skipping breakfast; pickiness; number of snacks taken; frequency in dining out, watching TV, and using computers; and the dietary supplement intake.

The finding from the study was similar to that of Yoon et al. [15] that vitamin and mineral products were the most frequently given to children at 77.5%, followed by red ginseng, ginseng, and Oriental medicines at 49.3%; yogurt and medicines for intestinal disorders at 25.6%; colostrum nutrients at 8.5%; and height growth nutrients at 8.0%. Red ginseng, ginseng, and Oriental medicines took the second highest portion of the dietary supplements for children. Kim et al. [26] reported that 59.2% of the primary school students in the metropolitan area took Oriental medicines. The impact of food on the health should be investigated in future long-term studies with a substantial number of subjects, as only few studies assessing the Oriental medicine intakes of children have been conducted thus far. However, several studies have been conducted on the adverse effects of Oriental medicine on children because of the technical difficulties in performing such studies on children [27-29]. Therefore, herbal supplements and treatments without verification on efficacies and stability should not be administered to children, with more attention required especially in young children. A study reported that the major types of dietary supplements for children were chewable tablets (33.2%) and jellies (23.4%), which were recommended only to children older than 3 years, who were able to chew at this age. In addition, the study indicated that 82 of the145 children were given dietary supplements (56.5%) in the form of chewables or jellies. This means that the parents did not follow the instructions on the product labels, increasing their children's risks of intra-airway aspiration. Even worse, most of the dietary supplements in the market raises concerns on overdose because the products were manufactured with shapes and colors that are attractive and sweet tastes that are appealing to children.

Recklessly taking dietary supplements while having balanced meals based on the recommended nutritional intake provides added benefit to improve nutritional or health status. Instead, this may cause overdose of certain nutrients and toxic effects [30]. Even worse, minerals were reported to have a narrow range of proper intake between the deficiency and toxic amounts compared with other nutrients, implying that the toxicity level is easily reached [31].

Previous studies in Korea showed that 18-33% of young Korean children were given more than 2 dietary supplements [3,32]. In particular, 45.5% of the children took 2 dietary supplements and 19.5% took more than 3 supplements. When interviewed, 36.4% of the children responded that they took the supplements "more than 6 months." This may be caused by the fact the some companies sell 2 or 3 types of supplements per packages or recommend the intake of these supplements using exaggerated advertisements. Taking more than 2 supplements simultaneously has raised a concern in that certain nutrients may be duplicated, leading to overdose. Song and Kim [21] reported that the amount of vitamin intake of preschoolers was generally twice to 7 times higher than the recommended allowance. Bailey et al. [33] indicated that more than one third of children aged between 2 and 18 years were given vitamin D and calcium supplements below the recommended level in addition to other dietary supplements and that 70% of the children aged between 2 and 8 years were given excessive amounts of other nutrients. These suggest that the children were recklessly given dietary supplements without knowledge of the common nutritional deficiencies during the infant and toddler periods [10].

Furthermore, the study showed that 92.6% of the mothers who provided dietary supplements to their children answered "healthy" or "normal" regarding their consciousness of their children's health and that only 7.5% of the mothers answered "not healthy." Among the respondents, 95.9% answered that they took dietary supplements when their children were healthy, and 4.1%, when their children were ill, which means that the children took dietary supplements when healthy. This is contrary to the guideline that dietary supplements are not required, except in case of poor nutrition, chronic diseases and meals with poor nutritional values [11,34]. Among the respondents, 63.0% answered that efficacies and nutrients were the most important among the items listed on the nutritional label, followed by cautions and adverse effects for 6.4% and storage and intake for 5.8% of the respondents. The reasons for checking the nutrition labels were to achieve information about efficacies and nutrition (58.6%), check the safety (24.8%), and harmful side effects (1.2%), suggesting that most mothers have greater interests in the efficacies rather than in the cautions or harmful side effects of the dietary supplements. Chung [12] investigated whether people knew that fat-soluble vitamins and minerals are harmful when taken in excess and found out that only 45.4% of the respondents answered yes and 46.5% of the respondents in the intake group answered, "There are no remarkable changes in the health before and after the children took dietary supplement." However, 97.6% of the intake group stated that they would continue giving their children dietary supplements and 62.2% of their counterparts indicated that they planned to give dietary supplements to their children, suggesting that both groups showed a positive response to dietary supplement intake. These perspectives may be due to the fact that dietary supplements were recklessly used owing to the Internet, exaggerative advertisements, and insufficient medical information, causing people to only recognize positive aspects of the dietary supplements. The information source used when considering the purchase of dietary supplements indicated that 48.2% of the respondents relied on recommendations from family members and friends, 23.4% judged by themselves, 11.2% followed recommendations from pharmacists, and 6.1% complied with physician prescription, similar to those reported in previous studies [10,15]. The purchase venues consisted of pharmacies for 33.0%, the Internet and mail orders for 21.7% and health functional food shops for 18.1% of the respondents. Most respondents achieved nutrition information, of whom 44.9% and 17.1% indicated the Internet and acquaintances as the source, respectively, and only 30.8% of the mothers reported that they consulted physicians and pharmacists about the dietary supplement intake of their children.

The result of this study shows that a variety of health functional products are introduced in the market, most of which are sold to those who do not possess special knowledge. These have led to reports of damages, including infusing harmful materials, allergic reactions, interactions with medical products and nutritional overdose. A report by the KFDA in 2010 revealed a total of 378 damages due to health functional products from 2006 to 2010 [35]. Furthermore, not many physicians had interest in the dietary supplement intake of children and not many provided clear answers when they received such questions [36]. Therefore, experts including pediatricians should educate parents that it is much more important for infants and toddlers to cultivate habits to eat balanced meals than to take supplements and that parents should provide dietary supplements to children with chronic diseases, poor growth, or fail to eat healthy meals. In addition, nutrients with high risks of adverse effects or toxicity based on the risk category of the nutrients should not be taken in excess of the upper limit, especially in children. Parents should follow guidelines when using dietary supplements and be aware of the products recognized and approved as health functional products [11]. Finally, pediatricians should educate parents to have proper knowledge of the harmful side effects of dietary supplements and the nutrients that are commonly deficient or those with high risk of toxicity when taken in excess of the recommended allowance for children age groups.

The study is limited to 3 cities in Korea and in the aspects of typicality and objectiveness because the study was based on the questionnaires completed by mothers who visited hospitals and thus failed to perform an accurate analysis of excessive or insufficient nutrients because it does not measure the amount of nutrition intake. However, the objective of the study was to investigate the trends and related factors in the intake of dietary supplements for preschoolers, the results of which are useful for proposing the importance and directions in the proper nutrition intake of preschoolers. Further large-scale studies are required to objectively understand the dietary supplement intake and nutritional status of children by complementing the various limitations of the present study.

Go to :

References

1. Jung JA. Foods for infants and children added or fortified nutrients. In : Proceeding of the 4th symposium of the Korean society of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition; 2010 Mar. 21; Seoul. Seoul: Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition;2010.

2. Choi HJ. Nutritional supplements intake and related factors of elementary school students in Seoul area. Seoul: Univ. of Sungshin;2009.

3. Kim EM, Jung HJ, Jeong JW, Kim JW. Analysis of elementary students' intake of dietary supplements. Korean J Food Cookery Sci. 2008; 24:672–681.

4. Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC). Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. accessed on 20 October 2010. Available at http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr.

5. Kretchmer N, Zimmermann M. Infancy and nutrition. In : Kretchmer N, Zimmermann M, editors. Developmental nutrition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon;1997. p. 30.

6. Wright AL, Holberg C, Taussig LM. Infant-feeding practices among middle-class Anglos and Hispanics. Pediatrics. 1988; 82:496–503. PMID: 3405686.

7. Yom HW, Seo JW, Park H, Choi KH, Chang JY, Ryoo E, et al. Current feeding practices and maternal nutritional knowledge on complementary feeding in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2009; 52:1090–1102.

8. Lee J, Kim D, Lee Y, Koh E, Jang Y, Lee H, et al. Influencing factors on the dietary supplements consumption among children in Korea. Korean J Community Nutr. 2011; 16:740–750.

9. Min IJ. A study on dietary life habits, food preference of the infants, and knowledges and attitudes of teachers and parents about nutrition, and growth and problem behavior of the infants. Seoul: Univ. of Kyung Hee Early Childhood Education;2009.

10. Kim YH, Lee SG, Kim SH, Song YJ, Chung JY, Park MJ. Nutritional status of Korean toddlers: from the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey 2007~2009. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011; 14:161–170.

11. Lee GS. Dietary supplements of toddlers. In : Proceeding of the 7th symposium of the Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition; 2013. p. 1–5.

12. Chung KH. Current situation and mangement policy on vitamin and mineral as health functional foods. Health Welf Policy Forum. 2009; 155:41–49.

13. Yi HH, Park HA, Kang JH, Kang JH, Kim KW, Cho YG, et al. What types of dietary supplements are used in Korea? Data from the Korean national health and nutritional examination survey 2005. Korean J Fam Med. 2009; 30:934–943.

14. Picciano MF, Dwyer JT, Radimer KL, Wilson DH, Fisher KD, Thomas PR, et al. Dietary supplement use among infants, children, and adolescents in the United States, 1999-2002. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007; 161:978–985. PMID: 17909142.

15. Yoon JY, Park HA, Kang JH, Kim KW, Hur YI, Park JJ, et al. Prevalence of dietary supplement use in Korean children and adolescents: insights from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2009. J Korean Med Sci. 2012; 27:512–517. PMID: 22563216.

16. Sichert-Hellert W, Kersting M. Vitamin and mineral supplements use in German children and adolescents between 1986 and 2003: results of the DONALD Study. Ann Nutr Metab. 2004; 48:414–419. PMID: 15665507.

17. Shaikh U, Byrd RS, Auinger P. Vitamin and mineral supplement use by children and adolescents in the 1999-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: relationship with nutrition, food security, physical activity, and health care access. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009; 163:150–157. PMID: 19188647.

18. Vernacchio L, Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Mitchell AA. Vitamin, fluoride, and iron use among US children younger than 12 years of age: results from the Slone Survey 1998-2007. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011; 111:285–289. PMID: 21272704.

19. Yu SM, Kogan MD, Gergen P. Vitamin-mineral supplement use among preschool children in the United States. Pediatrics. 1997; 100:E4. PMID: 9346998.

20. Lim JW. The changing trends in live birth statistics in Korea, 1970 to 2010. Korean J Pediatr. 2011; 54:429–435. PMID: 22253639.

21. Song BC, Kim MK. Patterns of Vitamin-Mineral Supplement Use among Preschool Children in Korea. Korean J Nutr. 1998; 31:1066–1075.

22. Han JH, Kim SH. Vitamin.mineral supplement use and related variables by Korean adolescents. Korean J Nutr. 1999; 32:268–276.

23. Sin YJ, Kim YH. Early childhood care and education in an aging Korea. Seoul: KIHASA;2012. p. 131–134.

24. Ryou HJ, Nam HJ, Min YH, Kim YJ, Park HR. Analysis of food habits and nutrients intake of nursery school children living in Anyang city, based on Z-score of weight for height. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2004; 10:1–12.

25. Kleinman RL. Pediatric nutrition handbook. 6th ed. Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics;2009. p. 155–156.

26. Kim MK, Jung JH, Min DL, Lee HJ, Park EJ. Study to examine the awareness of the parents, whose children are attending an elementary school in Gyeonggi-do, on herbal medication and health functional food. J Korean Oriental Pediatr. 2011; 25:111–118.

27. Walker WA. Eat, play, and be healthy: the Harvard Medical School guide to healthy eating for kids. New York: McGraw-Hill;2005.

28. Lohse B, Stotts JL, Priebe JR. Survey of herbal use by Kansas and Wisconsin WIC participants reveals moderate, appropriate use and identifies herbal education needs. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006; 106:227–237. PMID: 16442871.

29. Niggemann B, Grüber C. Side-effects of complementary and alternative medicine. Allergy. 2003; 58:707–716. PMID: 12859546.

30. Kim YJ, Mun JA, Min H. Supplement dose and health-related life style of vitamin-mineral supplement user among Korean Middle-Aged. Korean J Community Nutr. 2004; 9:303–314.

31. Chang NS, Choi YS, Min HS. Safe upper levels of vitamins and minerals in functional foods. In : Proceeding of Korean Nutrition Society; Seoul: Korean Nutrition Society;2005. p. 32–36.

32. Park JS, Lee JH. Elementary school childrens intake patterns of health functional foods and parents requirements in Daejeon area. Korean J Community Nutr. 2008; 13:463–475.

33. Bailey RL, Fulgoni VL 3rd, Keast DR, Lentino CV, Dwyer JT. Do dietary supplements improve micronutrient sufficiency in children and adolescents? J Pediatr. 2012; 161:837–842. PMID: 22717218.

34. Allen RE, Myers AL. Nutrition in toddlers. Am Fam Physician. 2006; 74:1527–1532. PMID: 17111891.

35. Jung KH. Research direction for functional foods safety. J Food Hyg Saf. 2010; 25:410–417.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download