Abstract

Purpose

Interest in peptic ulcer in children has been relatively low because the disease is rarer in children than in adults and there were restrictions in the application of endoscopy to children, but the recent development of pediatric endoscopy is activating research on pediatric peptic ulcer. Thus, this study compared the H. pylori infection rate and clinical and endoscopic findings among pediatric patients diagnosed with peptic ulcer.

Methods

We analyzed retrospectively 58 pediatric patients for whom whether to be infected with H. pylori was confirmed selected out of pediatric patients diagnosed with gastric ulcer or duodenal ulcer through upper gastrointestinal endoscopy at the Department of Pediatrics of Gachon University Gil Hospital during the period from January 2002 to December 2007. A case was considered H. pylori positive if H. pylori was detected in the Giemsa stain of tissue or the results of UBT (urea breath test) and CLO (rapid urease test) were both positive.

Results

Of the pediatric patients, 37 were infected with H. pylori and 21 were not. The H. pylori infection rate increased with aging and the result was statistically significant (p<0.05). However, H. pylori infection was not in a statistically significant correlation with sex, chief complaint, and gastroduodenal ulcer (p>0.05).

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a helical Gram-negative bacterium having 4-6 flagella on one end, and was known to the world in 1983 when Barry Marshall and Robin Warren succeeded in culturing H. pylori in human gastric mucosa [1,2]. H. pylori is the pathogen of chronic active gastritis, and is closely connected to the occurrence of duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, stomach cancer, MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) lymphoma, etc. Moreover, it has been reported to be associated with non-gastrointestinal general symptoms such as iron deficiency anemia, protein losing enteropathy, chronic idiopathic thombocytopenic purpura, and malabsorption [3-7].

On the other hand, interest in gastroduodenal ulcer in children has been relatively low because the disease is rarer in children than in adults and there were restrictions in the application of endoscopy to children, but the recent development of pediatric endoscopy is activating research on pediatric gastroduodenal ulcer [8]. It has already been known that duodenal ulcer is in close connection to H. pylori infection, and it was reported that among Korean pediatric patients 65% of duodenal ulcer cases and 32% of gastric ulcer cases were H. pylori positive [9].

Considering that if H. pylori infection occurs at a young age and is not treated, the infection may last throughout the lifetime, it is important to diagnose and treat the disease properly during childhood [10].

Thus the authors compared clinical and endoscopic findings according to the presence of infection with H. pylori in pediatric patients with gastroduodenal ulcer diagnosed through upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

There were 1,389 cases of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy conducted at the endoscopy unit of the Department of Pediatrics of Gachon University Gil Hospital for 6 years from January 2002 to December 2007, and among them 114 pediatric patients were diagnosed with gastric or duodenal ulcer. We excluded those having diseases such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura and Crohn's disease known to cause ulcer, those with ulcer caused by the intake of foreign substances, and those whose infection with H. pylori could not be tested as in neonates or was not tested for some reason, and used 58 pediatric patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer for whom whether to be infected with H. pylori was confirmed as the subjects of this study.

We reviewed the subject pediatric patients' medical records, endoscopic findings, and the results of UBT (urea breath test) and histological examination retrospectively. The endoscope used for diagnosis was Olympus GIFXP 160 (Tokyo, Japan), and biopsy was conducted for the gastric antrum, gastric body, and duodenal mucosa. A case was considered H. pylori positive if H. pylori was detected in the Giemsa stain of tissue or the results of UBT and CLO (rapid urease test) were both positive.

Collected data were processed using a statistical program (MedCalc for Windows, version 12.1.4 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium)), and the relations of H. pylori infection with age, chief complaint, and gastroduodenal ulcer were analyzed through Chi-square test and Chi-square test for trend. In each statistical test, the significance of result was accepted if p<0.05.

There were 58 pediatric patients who visited the Department of Pediatrics of Gachon University Gil Hospital and were diagnosed with gastroduodenal ulcer and whose infection with H. pylori was confirmed. Of them, 39 were male and 19 were female, so the sex ratio was 2.1:1. The subjects' ages were 8.6 years on the average and ranged between 1 and 16.

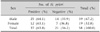

Among the 58 pediatric patients, the number of H. pylori positive ones was 0 in the age group 0-1 (0.0%), 9 (60.0%) in 2-6, 17 (60.7%) in 7-12, and 11 (84.6%) in 12 and older, so a total of 37 children were infected with H. pylori. The pediatric patients' age and H. pylori infection showed a statistically significant correlation with each other (p=0.041) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

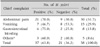

As to the correlation between the pediatric patients' chief complaints and H. pylori, the numbers of patients visiting for abdominal pain, vomiting and gastrointestinal bleeding as the chief complaint were 30 (51.7%), 15 (25.9%) and 8 (13.8%), respectively, and among them, 21 (70.0%), 7 (46.7%) and 6 (75.0%), respectively, were H. pylori positive. Five (8.6%) of the patients were examined for anemia, anorexia, general weakness, etc., and 3 of them (60.0%) were found to be H. pylori positive. There was no significant correlation between H. pylori and chief complaints (p=0.298) (Table 2).

Of the 58 patients, 25 (43.1%) were diagnosed with gastric ulcer and 30 (51.7%) with duodenal ulcer, and 15 (60.0%) and 20 (66.7%) of them, respectively, were found to be H. pylori positive. Three patients (5.2%) had both gastric ulcer and duodenal ulcer, and 2 (66.7%) of them were H. pylori positive (Table 3).

The correlation between gastroduodenal ulcer and H. pylori infection was not statistically significant (p=0.931).

In the results of investigating the endoscopic findings of 25 patients diagnosed with gastric ulcer, the numbers of patients showing erosive gastritis, nodular gastritis, hemorrhagic gastritis, and superficial gastritis were 10 (40.0%), 3 (12.0%), 4 (16.0%) and 8 (32.0%), respectively, and 6 (60.0%), 3 (100.0%), 2 (50.0%) and 4 (50.0%) of them, respectively, were H. pylori positive (Table 4). There was no endoscopic finding correlated with H. pylori infection in the pediatric patients with gastric ulcer (p=0.475).

In the results of investigating the endoscopic findings of 33 patients diagnosed with duodenal ulcer, the numbers of patients showing nodular gastritis, superficial gastritis, and reflux esophagitis were 16 (48.5%), 5 (15.1%) and 1 (3.0%), respectively, and 14 (87.5%), 1 (20.0%) and 1 (100.0%) of them, respectively, were H. pylori positive. There were 2 patients (6.1%) showing enlarged gastric mucosal fold in endoscopic findings, and both were H. pylori positive. Six patients (18.2%) did not have any particular finding except duodenal ulcer, and 2 (33.3%) of them were H. pylori positive (Table 5). Among endoscopic findings accompanying in pediatric patients with duodenal ulcer, nodular gastritis showed a significant correlation with H. pylori infection (p=0.028).

H. pylori is a helical Gram-negative bacterium having motile flagella, and is differentiated from Campylobacter mycetoma by fatty acid and the structural characteristics of 16s ribosome RNA sequence. Human is known to be the only host of this bacterium, and its infection route has not been explained clearly yet. There is evidence suggesting human-human transmission, but it is not clear whether the transmission is through the oral-oral route or through the fecal-oral route [11]. If H. pylori infects gastric mucosa, in most cases it causes an immune response and forms an antibody but this does not mean the removal of bacteria or the acquisition of immunity [12].

H. pylori is considered one of crucial factors causing chronic active gastritis and peptic ulcer not only adults but also in children [13], and with regard to the mechanism that H. pylori infection develops from an asymptomatic state to various diseases including peptic ulcer and gastric adenocarcinoma, there have been reports on the virulence factor of H. pylori and the host's immune response [14].

As criteria for determining H. pylori infection, several different 'gold standards' are being used and it is hard to say definitely which is most accurate, but common methods using biopsy tissue obtained through endoscopy are urease test (CLO test), histological methods such as H&E staining, Giemsa staining and Warthin Starry Silver staining, and the culture of H. pylori in a special medium [15].

Because these methods require biopsy tissue obtained through endoscopy, however, they have restrictions in diagnosis and treatment effect evaluation for children as it is not easy to apply endoscopy to children. Thus, mass screening, epidemiological investigation, etc. use H. pylori-specific IgG antibody test or non-invasive methods such as C13 or C14 breath test (UBT) and stool antigen test [16].

The criterion for H. pylori infection used in this study was that H. pylori was detected in endoscopic biopsy tissue treated through Giemsa stain or that the results of UBT and CLO were both positive.

The prevalence of H. pylori in children was reported to increase with aging. Egharia et al. [17] reported that H. pylori positive cases were found among children aged over 7, and among domestic studies Jung et al. [12] divided children into three age groups (10-11, 12-13 and 14-15), compared them and found that the prevalence of infection increased significantly with aging from 10.3% to 15.9% and 20.7%, respectively. In our study, children aged over 2 showed H. pylori infection and the prevalence showed a significant correlation with age.

According to the cause, pediatric peptic ulcer can be divided into primary ulcer associated with H. pylori infection, and secondary ulcer induced by other systemic diseases or drugs like NSAIDS [18]. Kim [19] reported that gastroduodenal ulcer was diagnosed in 22.5% of pediatric patients who received upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for acute abdominal pain, but our study showed relatively low prevalence of 8.2% probably because we included not only those with acute abdominal pain but also pediatric patients complaining of chronic symptoms.

Peptic ulcer may result in complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding, obstruction, perforation, etc. In Lee et al. [20] and Park et al. [21], bleeding was observed most frequently as 43.5% and 57.7%, respectively, and in our study, 13.8% of the pediatric patients found to have bleeding as a complication.

In children, H. pylori gastritis has a close correlation with duodenal ulcer [22]. A study in Toronto [23] reported that all of 13 pediatric patients with duodenal ulcer had chronic antral gastritis associated with H. pylori, and Hassel and Dimmick [24] followed up 27 pediatric patients with duodenal ulcer for 6 years and found that 23 of them had H. pylori positive chronic antral gastritis. There are also other reports that 90-100% of duodenal ulcer patients showed evidence for H. pylori gastritis [25,26]. Accordingly, we can say that primary duodenal ulcer without evidence for H. pylori infection is very rare. In this study, however, only 66.7% of pediatric patients diagnosed with duodenal ulcer were H. pylori positive and this rate was lower than previous reports. This result is probably because we did not exclude pediatric patients administered with antibiotic, bismuth drug, histamine inhibitor or proton pump inhibitor within 4 weeks before endoscopy.

With regard to the association between H. pylori infection and gastroesophageal reflux, studies with adults reported that H. pylori inhibits reflux esophagitis by inducing atrophic gastritis, but the mechanism in children is not clear. Aeri et al. [27] reported that H. pylori infection in children was in a positive correlation with the incidence of reflux esophagitis, and in our study reflux esophagitis was observed in one patient with duodenal ulcer and the case was H. pylori positive but we could not determine the correlation between the two factors because the number of patients was too small.

As to other endoscopic findings accompanying duodenal ulcer, nodular gastritis was most frequent (48.5%) as reported by Kim et al. [28], which was followed by non-specific finding (18.2%) and superficial gastritis (15.1%).

As endoscopic findings accompanying gastric ulcer, nodular gastritis was most frequent (43.3%) and it was followed by erosive gastritis (16.7%) and hemorrhagic gastritis (11.7%) in Lee et al.8), but in our study, erosive gastritis was most frequent (40.0%) and was followed by superficial gastritis (32.0%) and hemorrhagic gastritis (16.0%).

Summing up these results, in pediatric patients with gastroduodenal ulcer, H. pylori infection was not correlated with clinical symptoms. Among endoscopic findings accompanying in duodenal ulcer pediatric patients infected with H. pylori, nodular gastritis showed a significant correlation with H. pylori infection, but the correlation was not observed in gastric ulcer patients. H. pylori infection was not in a statistically significant correlation with gastroduodenal ulcer, but the H. pylori positive rate showed a significant correlation with age.

Future research may need to examine prospectively the relation between H. pylori and gastroduodenal ulcer in the Incheon area.

References

1. Lee A, O'Rourke J. Gastric bacteria other than Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993. 22:21–42.

2. Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984. 1:1311–1315.

3. Faigel DO, Furth EE, Childs M, Goin J, Metz DC. Histological predictors of active Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Dis Sci. 1996. 41:937–943.

4. Sarker SA, Mahmud H, Davidsson L, Alam NH, Ahmed T, Alam N, et al. Causal relationship of Helicobacter pylori with iron-deficiency anemia or failure of iron supplementation in children. Gastroenterology. 2008. 135:1534–1542.

5. Hill ID, Sinclair-Smith C, Lastovica AJ, Bowie MD, Emms M. Transient protein losing enteropathy associated with acute gastritis and Campylobacter pylori. Arch Dis Child. 1987. 62:1215–1219.

6. Kato S, Sherman PM. What is new related to Helicobacter pylori infection in children and teenagers? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005. 159:415–421.

7. Sullivan PB, Thomas JE, Weight DG, Neale G, Eastham EJ, Corrah T, et al. Helicobacter pylori in Gambian children with chronic diarrhea and malnutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1990. 65:189–191.

8. Rhee KS, Park JO. Gastroduodenoscopic findings and effect of therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005. 8:12–20.

9. Seo JK. Recurrent abdominal pain in children. J Korean Med Assoc. 1999. 42:859–867.

10. Valle J, Kekki M, Sipponen P, Ihamaki T, Siurala M. Long-term course and consequences of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Results of a 32-year follow-up study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996. 31:546–550.

11. Webb PM, Knight T, Greaves S, Wilson A, Newell DG, Elder J, et al. Relation between infection with Helicobacter pylori and living condition in childhood: evidence for person to person transmission in early life. BMJ. 1994. 308:750–753.

12. Jung MK, Kwon YS, Choe H, Choe YH, Hong YC. Relation between Helicobacter pylori infection and socioeconomic status in Korean adolescents. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000. 3:17–22.

13. Megraud F, Lamouliatte H. Helicobacter pylori and duodenal ulcer: Evidence suggesting causation. Dig Dis Sci. 1992. 37:769–772.

14. Yom HW, Seo JW. Gastric mucosal immune response of Helicobacter pylori-infected children. Korean J Pediatr. 2008. 51:457–464.

15. Barthel JS, Everett ED. Diagnosis of Campylobacter pylori infections: The "gold standard" and the alternatives. Rev Infect Dis. 1990. 12:s107–s114.

16. Brown KE, Peura DA. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993. 22:105–115.

17. Egbaria R, Levine A, Tamir A, Shaoul R. Peptic ulcers and erosions are common in Israel children undergoing upper endoscopy. Helicobacter. 2008. 13:62–68.

18. Bittencourt PF, Rocha GA, Penna FJ, Queiroz DM. Gastroduodenal peptic ulcer and Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2006. 82:325–334.

19. Kim YJ. Gastrointestinal mucosal lesions in children with short-term abdominal pain. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006. 9:176–182.

20. Lee SL, Kim YS, Suh ES, Paik TW, Kang CM. A clinical study on peptic ulcer in childhood. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1989. 32:198–205.

21. Park IS, Kim NS, Jung PM. Peptic ulcer disease in infants and children. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1995. 38:339–346.

22. Choe YH, Ko JS, Kim SY, Yoo YM, Seo JK. The eradication of Helicobacter pylori in the duodenal ulcer in children and the duodenal recurrence. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998. 1:30–36.

23. Drumm B, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Intrafamilial clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 1990. 322:359–363.

24. Hassall E, Dimmick JE. Unique features of Helicobacter pylori disease in children. Dig Dis Sci. 1991. 36:417–423.

25. Drumm B, O'Brien A, Cutz E, Sherman P. Campylobacter pylori-associated primary gastritis in children. Pediatrics. 1987. 80:192–195.

26. Kilbridge PM, Dahms BB, Czinn SJ. Campylobacter pylori-associated gastritis and peptic ulcer disease in children. Am J Dis Child. 1988. 142:1149–1152.

27. Moon A, Solomon A, Beneck D, Cunningham-Rundles S. Positive association between Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009. 49:283–288.

28. Kim HJ, Han HJ, An SG, Yoo JS, Kim HS, Tchah H, et al. Clinical and endoscopic findings in children with duodenal ulcer due to Helicobacter pylori infection. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1999. 42:69–76.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download