Abstract

Plastic surgeons who perform reconstructive surgery of facial injuries have a dual responsibility: repair of the aesthetic defect and restoration of the function. The third goal is to minimize the period of disability. although emergent situations are limited in facial injuries, I would like to emphasize the advantages of prompt definitive reconstruction of the injuries and the contribution of early operative intervention to the superior aesthetic and functional outcomes. Socioeconomic and psychological factors make it imperative that an aggressive, expedient, and well-planned surgical program be outlined, operated, and maintained to rehabilitate the patient to return to his or her active and productive life as soon as possible while minimizing aesthetic and functional disabilities. Teaching points: the techniques of extended open reduction and immediate repair or replacement of bone and microvascular tissue transfer of bone or soft tissue have made extensive and challenging injuries manageable. The principle of immediate skeletal stabilization in anatomic position has been enhanced by the use of rigid fixation and the application of craniofacial techniques that is safer and less traumatic for facial bone exposure. In this article, I will present mandibular fracture, orbital wall fracture and maxillar fracture, which are commonly encountered facial bone injuries. We can improve both the functional and aesthetic outcomes of facial fracture treatment when we manage the patients with the current concept of craniofacial techniques based on precise anatomic knowledge.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

The angle and direction in mandiblular fracture

A) vertical unfavorable, B) vertical favorable, C) horizontal unfavorable, D) horizontal favorable

Figure 2

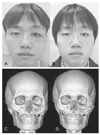

53 years old male patient with mandible condylar fracture who has operation using external fixator

A) Pre-operative 3D CT, B) Post-operative photo

Figure 3

Fixation points in zygoma fracture

1) zygomaticofrontal suture, 2) inferior orbital rim, 3) zygomaticomaxillary buttress, 4) zygomatic arch, 5) zygomaticosphenoidal suture

References

2. Paul NM. Stephen JM, editor. Facial fractures. Mathes plastic surgery. 2006. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier;77–380.

3. Stacey DH, Doyle JF, Mount DL, Snyder MC, Gutowski KA. Magement of mandible fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006. 117:48e–60e.

4. Zide MF, Kent JN. Indications of open reduction of mandibular condyle fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983. 41:89–98.

5. Haug RH, Barber JE, Reifeis R. An in vitro comparison of the effect of number and pattern of positional screws on load resistance. J Oral Mxillofac Surg. 1999. 57:300–308.

6. Neal DC, Wagner WF, Alpert B. Morbidity associated with teeth in the line of mandibular fractures. J Oral Surg. 1978. 36:859–862.

7. Shetty V, Freymiller E. Teeth in the line of fracture: a review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989. 47:1303–1306.

8. Constantin AL, Alexander B. Indications and limitations in resorbable P(L70/30KL)LA osteosyntheses of displaced mandibular fractures in 4.5-year follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006. 117:577–587.

9. Knight JS, North JF. The classification of malar fractures: an analysis of displacement as a guide to treatment. Br J Plast Surg. 1961. 13:325–339.

10. Lee J. Preplanned correction of enophthalmos using diced cartilage grafts. Br J Plast Surg. 2000. 53:17–23.

11. Yang SD, Lee EH. The use of acrylic splint for dental alignment in complex facial injury. J Korean Soc Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999. 26:910–916.

12. Schmitz JP, Hollinger JO. The critical size defect as an experimental model for craniomandibulofacial nonunions. Clin Orthop. 1986. 205:299–308.

13. Converse JM, Smith B, Obear MF, Wood-Smith D. Obital blowout fractures: a ten year survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967. 39:20–36.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download