Abstract

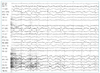

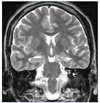

Aphysician faced with a patient who has an episodic disorder should determine whether the episode in question is indeed a seizure in the first place. If so, he or she should characterize its pattern and other characteristics, and finally, should delineate the underlying cause. Epilepsy is primarily a diagnosis based on a history and the initial assessment is based largely on the clinical history, especially on an accurate description of the event in question. The EEG, MRI, and routine blood tests should be included in the initial diagnostic workup. The EEG is undoubtedly the most sensitive, indeed indispensable, tool for the diagnosis of epilepsy, however, it must be used in conjunction with clinical data. A proportion of epileptic patients have a perfectly normal interictal EEG. Furthermore, a small number of healthy persons show paroxysmal EEG abnormalities. MRI is the most important diagnostic tool for the detection of structural abnormalities underlying epilepsy. Some patients may later need protracted video-EEG monitoring for the diagnosis of epilepsy. The conditions most likely to simulate a seizure are syncope and transient ischemic attacks. There is a rise in serum creatine kinase and serum prolactin levels after the seizure, which findings could be used in emergency room to assist in distinguishing seizures from syncope or pseudo-seizures.

References

1. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 1981. 22:489–501.

2. Commission on Classification and Terminology, International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia. 1989. 30:389–399.

3. Moshe SL, Pedley TA. Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Overview: Diagnostic evaluation. Epilepsy: a comprehensive textbook. 1997. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers;801–803.

4. Walczak TS, Jayakar P. Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Interictal EEG. Epilepsy: a comprehensive textbook. 1997. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers;831–848.

5. Marsan CA, Zivin LS. Factors related to the occurrence of typical paroxysmal abnormalities in the EEG records of epileptic patients. Epilepsia. 1970. 11:361–381.

6. Salinsky M, Kanter R, Dasheiff RM. Effectiveness of multiple EEGs in supporting the diagnosis of epilepsy: an operation curve. Epilepsia. 1987. 28:331–334.

7. Cascino GD. Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Structural brain imaging. Epilepsy: a comprehensive textbook. 1997. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers;937–946.

8. Brooks BS, King DW, el Gammal T, Meador K, Yaghmai F, Flanigin HF, et al. MRI imaging in patients with intractable complex partial epileptic seizures. Am J Neuroradiol. 1990. 11:93–99.

9. Jackson GD, Berkovic SF, Tress BM, Kalnins RM, Fabinyi GC, Bladin PF. Hippocampal sclerosis can be reliably detected by magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology. 1990. 40:1869–1875.

10. Victor M, Ropper AH. Adams and Victor's principles of neurology. 2001. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;331–365.

11. Pritchard PB. Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Hormone changes in epilepsy. Epilepsy: a comprehensive textbook. 1997. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers;1997–2002.

12. So NK, Andermann F. Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Differential diagnosis. Epilepsy: a comprehensive textbook. 1997. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers;791–797.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download