Abstract

Objective

The National Cancer Screening Program (NCSP) began in 1999. In this report, we evaluate the results of the NCSP for cervical cancer in 2009 and provide participation rates in an organized cervical cancer screening program in Korea.

Methods

Using data obtained from the National Cancer Screening Information System, cervical cancer screening participation rates were calculated. Recall rates, defined as the proportion of abnormal cases among women screened, were also estimated with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

The target population of cervical cancer screening in 2009 included 4,577,200 Korean women aged 30 and over, 1,349,668 of whom underwent the Papanicolaou smear test (29.5% participation rate). Compared with the participation rate of women covered by the National Health Insurance Program (31.3%), the participation rate of women covered by the Medical Aid Program was lower (18.4%). Participation rates also varied in different age groups (the highest of 39.3% in women aged 50 to 59 and the lowest of 14.4% in those aged 70 and older), and different areas (the highest of 34.1% in Busan and the lowest of 21.5% in Chungnam). The overall recall rate for cervical cancer screening was 0.41% (95% confidence interval, 0.40 to 0.42).

Cervical cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer death among women worldwide, despite implementation of the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear test, which has dramatically decreased the incidence of cervical cancer in developed nations over the past 30 years [1]. Cervical cancer incidence and mortality have been decreasing continuously in Korea. However, cervical cancer remains a clinically important disease; in fact, it is the sixth most common cancer among women and first among female genital malignancies. Thus, it is a major health problem for Korean women. Indeed, in 2008, an estimated 3,888 new cases were diagnosed, accounting for 4.5% of new female cancer cases. The incidence rate per 100,000 women was 11.2 in 2008, down from a high of 16.3 in 1999. Survival rates have also improved [2].

Since population-based cervical cancer screening was introduced, cervical cancer screening, including opportunistic as well as organized screening, has been widely available [3,4]. Currently, two population-based organized cancer screening programs exist in Korea: the National Cancer Screening Program (NCSP), whose target population includes Medical Aid Program (MAP) recipients and the lower 50% of National Health Insurance (NHI) beneficiaries, and the NHI Cancer Screening Program (NHICSP), which is provided to the upper 50% of NHI beneficiaries by NHI Corporation. These two programs provide a screening test free of charge to all Korean women aged 30 and over, biennially [5].

In the present study, we sought to provide preliminary information on the NCSP for cervical cancer, based on data collected in 2009. This report describes participation rates and the percentage of abnormalities by age and insurance type. Results for the NHICSP will be reported by the NHI Corporation.

In this study, we utilized the database of the 2009 NCSP for cervical cancer. Korean women are instructed to be screened biennially, and the standard modality for cervical cancer screening is the Pap smear test. The target population for cervical cancer screening in the 2009 NCSP consisted of 4,577,200 women born in 1979 or earlier (i.e., aged 30 years and older, with a mean age of 51.9±11.0 years) who were MAP recipients or NHI beneficiaries in the lower 50% of the income bracket. For those NHI beneficiaries who were included in the NCSP, the insurance premium was US$ 60 (1 USD=1,000 KWR) or less per month for employees and US$ 72 or less per month for the self-employed (based on November, 2008).

Participation in the NCSP was confirmed based on claims and cervical cancer screening results submitted to the NHI Corporation before December 31, 2009. All screening was done between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2009. Some subjects underwent the same screening procedure multiple times; for those individuals, only the first screen was counted (n=11,465). These participants were only counted once in determining the participation rate.

The NCSP for cervical cancer reported Pap test results by using the 2001 Bethesda System categories [6]. The screening results were assigned to one of the following categories: normal, infection/reaction, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), squamous cell carcinoma, and "other". The category "other" included Pap smear results relating only to glandular elements of the genital tract and hormonal evaluations. Pap smear results were defined as abnormal if they were reported as LSIL, HSIL, adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), or squamous or adenomatous cell carcinoma [7].

The participation rate of cervical cancer screening was calculated by dividing the number of participants by the target population of the NCSP for cervical cancer, and is denoted as a percentage. Recall rates for cervical cancer screening were defined as the proportion of abnormal cases among the cancer-screened participants; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all recall rates. SAS ver. 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used in all statistical analyses.

Table 1 shows the screening outcomes by age, health insurance type, and area of residence. The target population of the 2009 NCSP for cervical cancer screening included 4,577,200 females; among them, 1,349,668 underwent the Pap smear test, giving a participation rate of 29.5%. In terms of age, the participation rate was highest (39.3%) among females aged 50 to 59 years and the lowest (14.4%) among those aged 70 years and older. Regionnally, while the participation rate was the highest (34.1%) in Busan, which is the second largest city in Korea, it was the lowest (21.5%) in Chungnam, which is a rural area.

Recall rates in women aged 70 years and older and in their 30s, in contrast to the participation rates, were higher than those in the other age groups. Among the age groups, the range of recall rates for women in the NHI program was 0.31-0.51%; however, for those who were MAP recipients, the range was 0.30-0.68%, making the recall rate of women aged 70 years and older and in their 30s twice that of women in their 50s. Except for women in their 50s, in each age group the recall rate for women who were MAP recipients was higher than that for women who were NHI beneficiaries (Table 1).

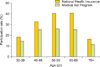

The number of participants among NHI beneficiaries decreased with age, whereas the number of participants who were MAP recipients did not change with age (Fig. 1). The overall participation rate of NHI beneficiaries was higher than that of MAP recipients (31.3 and 18.4%, respectively). Additionally, the participation rate of NHI beneficiaries compared with MAP recipients was higher for all age groups (Fig. 2). The participation rates in women aged 70 years and older and in their 30s were lower than those for the other age groups. The same was true for women who were NHI beneficiaries and MAP recipients. Women who were MAP recipients were estimated to have lower participation rates than those in the NHI group for each age group.

Of all participants, 0.41% (5,529) represented abnormal cases. Compared with health insurance beneficiaries, the rate of abnormal cases involving MAP recipients was higher than those involving NHI beneficiaries by 0.12%. Regarding age, the abnormal rate decreased for older women but increased sharply for women aged 70 years and older (Table 2). The U-shaped curve representing abnormal tests by age diverged from 0.48% for women in their 30s, reached a minimum (0.33%) for women in their 60s, and approached 0.56% for women aged 70 years and older (Fig. 3). With increasing age, the proportion of LSILs reported decreased, while the proportions of HSILs and squamous cell carcinoma increased.

The participation rate in the 2009 NCSP for cervical cancer was 29.5%. Participation rates have tended to increase since the first participation rate for cervical cancer screening in the NCSP was estimated at 15.4% in 2002 [5]. However, the rate remains at a lower level compared with those in countries that have established screening programs, although it is higher than that in Japan which is also located in Asia. Regarding Europe, fourteen countries operate cervical cancer prevention programs, and their participation rates reportedly range from 10 to 79% [8]. Northern European countries that launched a similar program in the 1960s, including Finland, Sweden, and Denmark, report participation rates in excess of 75% [9]. The US has a National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), which was adopted in 1991 and which provides low-income, uninsured, and minority women with screening and diagnostic services for breast and cervical cancer; that program's participation rate for cervical cancer screening is 78.3% [10-12]. In 1998, the UK implemented the NHS Cancer Screening Program for women. In that country, the Pap smear test had been used to detect cervical cancer, but the liquid-based cytology method replaced it in 2003. The participation rate for cervical cancer screening in the UK was 78.9% as of March, 2009 [13]. In Japan, local governments instituted a cancer detection program in the 1960s; however, this was replaced by a national cancer detection program run by the central government upon establishment of the Health and Medical Services Law for the Aged. Cervical cancer screening started in 1982, and the participation rate was 18.8% in 2009 [14,15].

For early cancer detection programs, the participation rate is very important because early adoption of detection programs effectively lowers the incidence and mortality rate of cervical cancer, and the incidence rate decreases as an individual repeats the test [16]. In Sweden, which launched its cervical cancer early detection program in 1958, the number of patients in the terminal stage was dramatically reduced, making care for cancer patients more efficient [17]. In the US, women aged 18 years and over participate in cervical cancer screening tests every 3 years using the Pap smear test, and the incidence rate continues to decrease [10]. In Korea, a steady decline in both the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer has been observed; the incidence of cervical cancer decreased by 4.6% annually from 1999 to 2008 [2,18].

The NCSP for cervical cancer has shown a decreased incidence rate of cervical cancer and has had a positive effect on cancer management; however, several problems remain to be addressed. First, although the cervical cancer screening program is free of charge to participants, the participation rate among MAP recipients was 18.4%, which is much lower than that among NHI beneficiaries (31.3%). Moreover, the recall rate of MAP recipients was 0.52%, which is higher than that of NHI beneficiaries (0.40%). Regarding the US, as socioeconomic status is lowered, the incidence rate increases [19], and as the cumulative number of participants undergoing screening increases, the prevalence rate decreases [10]. In Korea, sociodemographic factors such as being married, having a higher education, a rural residence, and private health insurance were significantly associated with higher participation rates of cervical cancer screening. However, household income was not a significant factor. Additionally, the perception of not needing a Pap test due to good health or an absence of symptoms was the most frequently reported barrier to participation in cervical cancer screening [20]. Thus, stronger efforts are required to identify what obstructs MAP recipients from participating in the detection program and to develop proper institutional measures.

Second, regarding age, the participation and recall rates of women in their 30s were 17.9 and 0.48%, respectively. This represents the lowest and highest rates, respectively, except for women aged 70 years and older. Considering that the incidence rate among younger women is rising while the overall incidence rate is falling [21,22], women in their 30s must participate in a screening program to prevent cervical cancer. Additionally, the participation and recall rates of women aged 70 years and older were relatively low and high, respectively. Elderly women are said to be vulnerable to cervical cancer because they believe that menopause frees them from diseases involving the reproductive organs; thus, they tend not to participate in prevention programs. The US once limited the age of eligibility for the Pap smear test to 65 years; however, in a consensus statement announced at the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement on Cervical Cancer, women aged 65 and older were encouraged to continuously attend the screening program [23]. This implies that constant care for cervical cancer is needed after menopause, and the extension of average lifespan calls for extending the prevention period.

Differences in participation rates were identified according to health insurance type, age, and area of residence. Hence, along with improving the participation rate for cervical cancer screening, continuing efforts are required to minimize these differences. We expect that our results will be useful in creating policies and new studies to improve efforts to prevent cervical cancer in Korea.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Number of participants by health insurance type and age from the National Cancer Screening Program for cervical cancer, 2009.

Fig. 2

Participation rates by health insurance type and age from the National Cancer Screening Program for cervical cancer, 2009.

Fig. 3

Proportion of abnormal results by age from the National Cancer Screening Program for cervical cancer, 2009. LSIL, low-grade intraepithelial lesions; HSIL, high-grade intraepithelial lesions; SCC, squamous cell cancer.

Table 1

Screening outcomes by age, health insurance type, and area of residence from the National Cancer Screening Program for cervical cancer, 2009

Table 2

Distribution of Papanicolaou smear test results by age group and health insurance type in the National Cancer Screening Program for cervical cancer, 2009

Values are presented as number (%).

MAP, Medical Aid Program; NHI, National Health Insurance.

*Individuals without available screening results were excluded (n=11). †Includes low-grade intraepithelial lesions, high-grade intraepithelial lesions, adenocarcinoma in situ, and squamous or adenomatous cell cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research and Control from the National Cancer Center of Korea (#1010201-2).

References

1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005. 55:74–108.

2. Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, Park EC, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2008. Cancer Res Treat. 2011. 43:1–11.

3. Mun JY, Han MA, Lee HY, Jun JK, Choi KS, Park EC. Cervical cancer screening in Korea: report on the National Cancer Screening Programme in 2008. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011. (in press).

4. Lee EH, Lee HY, Choi KS, Jun JK, Park EC, Lee JS. Trends in cancer screening rates among Korean men and women: results from the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey (KNCSS), 2004-2010. Cancer Res Treat. 2011. 43:141–147.

5. Kim Y, Jun JK, Choi KS, Lee HY, Park EC. Overview of the National Cancer screening programme and the cancer screening status in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011. 12:725–730.

6. Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O'Connor D, Prey M, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002. 287:2114–2119.

7. Benard VB, Eheman CR, Lawson HW, Blackman DK, Anderson C, Helsel W, et al. Cervical screening in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1995-2001. Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 103:564–571.

8. Bastos J, Peleteiro B, Gouveia J, Coleman MP, Lunet N. The state of the art of cancer control in 30 European countries in 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010. 126:2700–2715.

9. Anttila A, Ronco G, Clifford G, Bray F, Hakama M, Arbyn M, et al. Cervical cancer screening programmes and policies in 18 European countries. Br J Cancer. 2004. 91:935–941.

10. Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2010: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010. 60:99–119.

11. Benard VB, Saraiya MS, Soman A, Roland KB, Yabroff KR, Miller J. Cancer screening practices among physicians in the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011. 20:1479–1484.

12. The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program 1991-2002 national report. US Department of Health and Human Service. 2005. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

13. NHS cervical screening England 2009-10 [Internet]. Health and Social Care Information Centre. 2010. cited 2011 Sep 15. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre;Available from: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/008_Screening/cervscreen0910/2009_10_Cervical_Bulletin_Final_Report_AI_v1F.pdf.

14. Health statistics in Japan 2010 [Internet]. Statistics and Information Department, Japan. 2011. cited 2011 Sep 15. Tokyo: Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare;Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/hoken/national/dl/22-00.pdf.

15. Aklimunnessa K, Mori M, Khan MM, Sakauchi F, Kubo T, Fujino Y, et al. Effectiveness of cervical cancer screening over cervical cancer mortality among Japanese women. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006. 36:511–518.

16. Jun JK, Choi KS, Jung KW, Lee HY, Gapstur SM, Park EC, et al. Effectiveness of an organized cervical cancer screening program in Korea: results from a cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2009. 124:188–193.

17. Pettersson BF, Hellman K, Vaziri R, Andersson S, Hellstrom AC. Cervical cancer in the screening era: who fell victim in spite of successful screening programs? J Gynecol Oncol. 2011. 22:76–82.

18. Shin HR, Park S, Hwang SY, Kim JE, Jung KW, Won YJ, et al. Trends in cervical cancer mortality in Korea 1993-2002: corrected mortality using national death certification data and national cancer incidence data. Int J Cancer. 2008. 122:393–397.

19. Liu T, Wang X, Waterbor JW, Weiss HL, Soong SJ. Relationships between socioeconomic status and race-specific cervical cancer incidence in the United States, 1973-1992. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998. 9:420–432.

20. Park MJ, Park EC, Choi KS, Jun JK, Lee HY. Sociodemographic gradients in breast and cervical cancer screening in Korea: the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey (KNCSS) 2005-2009. BMC Cancer. 2011. 11:257.

21. Han CH, Cho HJ, Lee SJ, Bae JH, Bae SN, Namkoong SE, et al. The increasing frequency of cervical cancer in Korean women under 35. Cancer Res Treat. 2008. 40:1–5.

22. Liu S, Semenciw R, Mao Y. Cervical cancer: the increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma in younger women. CMAJ. 2001. 164:1151–1152.

23. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement on cervical cancer, April 1-3, 1996. Gynecol Oncol. 1997. 66:351–361.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download