Abstract

Objective

Early stage primary carcinoma of the fallopian tube (PCFT) is an uncommon condition when strict criteria are applied. The aim of this study was to compare the outcome stage IA-IB PCFT to a matched group of ovarian cancer (OC).

Methods

Between 1990 and 2008, 32 patients with stage IA-IB of PCFT were recorded in the database of three French Institutions. A control group of patients with OC was constituted.

Results

Eleven eligible PCFT cases and 29 OC controls fulfilled the stringent inclusion criteria. Median follow-up was 70.2 months. Five-year overall survival was 83.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 27.3 to 97.5) for PCFT and 88.0% (95% CI, 66.9 to 96.0) for OC (p=0.93). In the subgroup of patients with grade 2-3, the outcome was similar in PCFT compared to OC patients (p=0.75). Five-year relapse-free survival was respectively 62.5% (95% CI, 22.9 to 86.1) and 85.0% (95% CI, 64.6 to 94.2) in the PCFT and OC groups (p=0.07). In the subgroup of patients (grade 2-3), there was no difference between PCFT and OC (p=0.65).

Primary carcinoma of the fallopian tube (PCFT) accounts for about 0.3% to 1.8% of all gynecologic cancers [1]. PCFT is a rare tumor compared to ovarian carcinoma [2]. Advanced - stage III/IV - fallopian tube cancer is quite difficult to distinguish from advanced ovarian cancer (OC). Baekelandt et al. [3] in a series of 151 fallopian tube cancer patients, the 5-year survival was 29% for stage III and 12% for stage IV, compared to 73% in stage I. Published data recommend the same treatment and follow-up strategy for advanced stage of ovarian and fallopian tube cancer, due to their similar physiopathology, natural history, clinical characteristics, and prognosis.

The available data on the outcome of early fallopian tube cancer limited to one or both tubes (stage IA-IB) is mainly made of small sized case series. Early fallopian tube cancer is generally managed in the same way as early OC, with the assumption that the prognoses of the two cancers are similar. However, comparisons of clinical outcomes of patients with fallopian and OC, respectively, have been quite few. A recent retrospective case control study demonstrated that, for advanced stage PCFT, a similar survival outcome is obtained compared to OC patients, whereas the survival was better for early stage PCFT compared to OC [4]. Wethington et al. [5], in an important retrospective comparison-control study, compared the outcome of 55,825 patients suffering from PCFT and OC. They found that early and advanced stage PCFT have a better overall survival than OC.

However, current studies included patients that were not comprehensively staged and did not mention review of the pathology with reassessment of pathological grade. It is thus likely that stage IIIC patients with nodal spread and/or early OCs were included in groups of apparently early stage patients [6]. The question of whether or not early fallopian tubal cancer has a different outcome compared to early OC of similar grade is thus still open. The aim of this study was to compare the outcome of carefully studied and staged stage IA-IB PCFT to a matched group of OC.

Between January 1990 and December 2008, 32 patients with stage IA-IB invasive epithelial malignancies of the fallopian tube were recorded in the database of three French institutions (Claudius Regaud Institute, Toulouse; Gustave Roussy Institute, Villejuif; and Oscar Lambret Center, Lille).

Stringent criteria were used for patient selection. Pathologic findings were reviewed by specialized pathologists in each center, whenever possible on the original slides. Only patients presenting the following criteria were selected: 1) invasive epithelial fallopian tube carcinoma, 2) serous, mucinous, and endometrioid histological subtypes, 3) complete surgery including hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and lombo-aortic lymphadenectomy, omentectomy, peritoneal washings (multiple random peritoneal biopsies and appendectomy were optional); complete surgery, by open approach or laparoscopy, completed at the time of primary surgery or at the time of surgical reassessment after incomplete surgery, 4) stage IA or IB (lymph node negative) according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) criteria established in 1991 after comprehensive staging, 5) defined pathological grade according to World Health Organization (WHO) classification [7], 6) adjuvant chemotherapy had to have been administered at least to patients with a stage IA grade 3 (G3), in which case a minimum number of three cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy was mandatory, and 7) at least one year of follow-up.

Among the 32 potentially eligible patients, 21 were excluded for one or several missing criteria. Ten patients were incompletely staged, as aortic and pelvic lymph node dissection was not performed in seven cases, aortic dissection in three additional cases. Four patients were upstaged after reassessment (one stage IIA, one stage IIC, two stage IIIC). Five patients were excluded after review of pathology: undetermined pathological type and original slides not available in two patients, endocrine tumor type in one case, an intraepithelial tumor in two patients. Grade was not described in seven patients (among these patients four were also excluded because of incomplete staging, and one patient had an intraepithelial tumor). Overall, only 11 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and made our study group.

We constituted a group control with 29 patients with OC (stage IA-IB), using the same stringent inclusion criteria used for PCFT. The initially control group contained 76 patients with OC (stage IA-IB). Forty seven patients were excluded for one or several missing criteria, of whom 13 were clear cells carcinomas. Controls were selected without knowledge of patient outcome (Fig. 1).

Data were summarized by frequency and percentage for categorical variables and by median and range for continuous variables. To assess differences in clinicopathologic features between groups, chi square or Fisher's exact test was used for qualitative variables and the Mann-Whitney test was used for continuous variables.

Overall survival and relapse-free survival were calculated from the date of the surgery. The first-event definitions were death from any cause for overall survival, local regional or distant recurrence for relapse-free survival. For overall survival, patients alive at the last follow-up news were censored. For relapse-free survival, patients alive without disease were censored at the last follow-up news. Survival rates were estimated according to the Kaplan-Meier method and the log rank test was used to assess the differences between the groups. All statistical tests were two sided, and differences were considered statistically significant when p<0.05. Statistical analysis was done with the Stata ver. 10.0 (Stata Co., College Station, TX, USA).

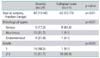

Patient's characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients with PCFT had more delivery (90% with at least one delivery) compared to patients with OC (48.1% with one or more delivery). Patients with PCFT were more frequently treated by previous hormonotherapy (n=4, 44.4%) compared to OC patients (n=2, 7.4%, p=0.02). Patients presenting with PCFT were older than patients with OC (median, 62 years vs. 43 years; p<0.01). The histological serous subtype was more frequent in the PCFT group (81.8%) than in the OC group (17.3%, p<0.01). PCFT were more often grade 2-3 (90.9%) than OC (51.7%, p=0.03). Four patients were tested for BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 (2 in the OC group and 2 other in the PCFT group). In those 4 patients, only one of PCFT group was muted and the mutation was BRCA2. The methodology applied was full sequencing in all patients. We observed that the trend was more pregnancies and status menopausal patients within the PCFT group.

Concerning modalities of surgery, all patients had complete surgery including hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and lombo-aortic lymphadenectomy, omentectomy, peritoneal washings (multiple random peritoneal biopsies and appendectomy were optional). An exception was made for the 6 younger patients to preserve fertility. They did not undergo hysterectomy and contralateral salpingo-oophorectomy during the first intention surgery. We therefore performed laparotomy for 16 patients in the PCFT group and 4 patients for the OC group, whereas laparoscopy was utilized for 9 patients in the PCFT group and 6 for the OC group. Four patients had a laparoscopy converted to laparotomy during surgery. For restaging, laparotomy was performed in 20 patients in the OC group (100.0%, 9 unknown) and 5 patients in the PCFT group (50.0%, 1 unknown), whereas laparoscopy was realized in 5 of the PCFT group (50.0%, p<0.01).

Adjuvant chemotherapy following surgical cytoreductive effort was respectively administered to 9 (81.8%) and 4 patients (13.8%) of the PCFT and OC groups, respectively (p<0.01). In combination with platinum chemotherapy regimen, some patients received paclitaxel (PCFT, 8 cases; OC, 3 cases), or cyclophosphamide (PCFT, 1 case; OC, 1 case).

The median follow-up was 70.2 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 57.1 to 108.4). A total of 4 deaths were observed, 1 in the PCFT and 3 in the OC group. The five-year overall survival was 83.3% (95% CI, 27.3 to 97.5) and 88.0% (95% CI, 66.9 to 96.0) for the PCFT and OC groups, respectively (p=0.93) (Fig. 2A).

In the subgroup of patients with grade 2 or 3, risk of death was not increased for PCFT compared to OC (p=0.75). The five-year overall survival was 80% (95% CI, 20.4 to 97.1) and 78.7% (95% CI, 47.3 to 92.7) for PCFT and OC (Fig. 2B), respectively.

Four patients in each group developed a recurrence. The characteristics of those 8 patients are detailed in Table 2. Among the patients in the PCFT group with recurrence, histological subtypes and grades were: endometrioid/G1 (n=1), serous/G2 (n=1), serous/G3 (n=2). In the OC group, 3 patients with recurrence were mucinous/G2 and 1 patient was serous/G3. Among eight patients with recurrence, four patients have received chemotherapy with platinum, two associated with paclitaxel, and two associated with cyclophosphamide. Recurrence sites were the pelvic peritoneum in four patients (among one peritoneum only), lymph nodes in three patients (mesorectum and lombo-aortic lymph node for one patient, associated with pelvic peritoneum for second patient and associated with retrovesical mass for the third patient), "peritoneal carcinomatosis for one patient," and atypical site for the last patient (drain orifice).

The treatment of the recurrence was chemotherapy for 7 patients: three in association with surgery and one with surgery and radiation therapy. Because of peritoneal extensive disease and no possibility of surgery resection, two patient's received only chemotherapy. For node recurrence just one patient was treated by chemotherapy. Only one patients recurrence was not specified. A total of 4 deaths were observed: 1 in the PCFT and 3 in the OC patient group.

The five-year relapse-free survival was 62.5% (95% CI, 22.9 to 86.1) and 85% (95% CI, 64.6 to 94.2) in the PCFT and OC groups, respectively (p=0.07) (Fig. 2C). In the subgroup of patients with grade 2-3, the 5-year relapse-free survival was estimated at 57% (95% CI, 17.2 to 83.7) and 72% (95% CI, 41.1 to 88.6) for PCFT and OC, respectively (p=0.65) (Fig. 2D).

Stage IA-IB PCFT is a very rare entity. It may be even rarer than expected considering that the majority of patients recorded in our database were excluded after careful review of data, suggesting that the available literature may be based on biased data. The careful selection process left a small number of remaining patients with stage IA-IB fallopian tube cancer, with no place for definitive conclusions. However, some interesting findings deserve comment.

There are few case-control studies comparing PCFT to OC. It is important to evaluate OS and progression free survival (PFS) to improve the management of PCFT including the early stages. Moore et al. [4] compared in a retrospective multi-institutional case-control study 96 women with serous PCFT to 189 patients with OC. The authors found that outcome was better for early stage PCFT compared to OC (95% vs. 76%). The conclusions are disputable as a result of many potentially confounding factors. First, there was a higher proportion of stage IA PCFT found incidentally at the surgery for benign indications. Second, more PCFT patients were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy compared to OC. These PCFT would be expected to have a favorable survival. Third, imbalance affected the matching process as stage IA was excluded. The five-year overall survival was 92% for PCFT patients and 70% for OC patients (p=0.04). The five-year progression free survival curves were not statistically significant at 62% and 50%, respectively (p=0.09) [4]. The analysis that all initially included stage of fallopian tube cancer was not complete because of the exclusion of early stage IA in this cohort. Another recent large retrospective study compared the clinical characteristics and outcomes for PCFT and OC (all stages confounded) retrieved from epidemiological databases [5]. The authors concluded that survival was similar for early stage (I and II) PCFT and OC (p=0.19). Although their study included a large number of patients, several flaws may be suggested. The databases lacked information on adjuvant therapy and cytoreductive status, on the quality of pathology review, and on the comprehensiveness of staging. Considering the high rejection rate in our study, it is likely that some non invasive tumors were included as invasive, and that a proportion of patients were actually stage IIIC in this paper and in other papers of the literature as well [5]. Our study is the only available one using strict inclusion criteria. Our results are also in accordance with the series of Baekelandt et al. [3], who found 73% OS and 61% PFS in stage I PCFT. In addition, the authors analysed prognostic factors of stage I PCFT and retained the depth of infiltration and tumor rupture in multivariate analysis. These factors seem to be different from prognosis factors of early ovarian carcinomas, in opposition to similarities in characteristics and prognosis between more advanced stage disease of tubal and ovarian carcinomas [3]. When comparing patients with similar grades, overall survival outcomes are similar between fallopian tube and OCs. However, there is a trend toward a decrease of relapse free survival in the PCFT group, even if the power of the study is too weak to reach statistical significance (p=0.07). This finding seems to be depend only on the higher proportion of high grade tumors in the PCFT group. Actually, stage IA grade 1 (G1) fallopian tube cancer is an extremely rare disease in our experience.

Moreover, it is important to know if the therapeutic care of PCFT should be duplicate to OC. In fact, the management of PCFT is usually similar to OC. First, complete cytoreductive surgery is the treatment of choice for PCFT [8]. As all patients were stage I, with no associated endometriosis, none of them underwent an anterior resection surgery. Deffieux et al. [6] reported in their study of 19 patients that 29% of stage I PCFT had positive lymph nodes. This finding stresses the need for a complete lymph node dissection including all pelvic and para-aortic chains up to the level of the left renal vein. Previous studies suggested early lymphatic spread of PCFT, even in apparent early stages [3,9-11]. The role of laparoscopic surgery is still controversial. In our study, we performed a laparotomy in the majority of cases in the PCFT and OC groups. Palpation is impossible during laparoscopy which offers a chance to detect small tumor in the porta hepatis, hepatophrenic junction, or omentum. For this reason, the possibility of biased patient inclusion or exclusion might occur in terms of tumor distribution. However, the actual trend according to Leblanc et al. [12], laparoscopy seems to be an acceptable technical option to performing restaging of apparently early adnexal carcinomas. Some areas - the posterior aspect of the liver, high part of left hemidiaphragm - are difficult to explore, but the likelihood of finding isolated implants in these areas is low.

In terms of adjuvant therapy, the PCFT is generally managed as OC. Several reports have found that patients who received platinum based chemotherapy responded well to these treatments [5,13-17]. Recently, in a larger study, Pectasides et al. [18] suggested the combination of carboplatin plus paclitaxel as the standard chemotherapy regimen for PCFT patients. In our clinical practice, intravenous adjuvant chemotherapy with platinum is recommended after complete surgical staging, for patients with stage IC or stage IA or IB, grade 3. Stage IA or IB grade 2 (G2) patients are proposed chemotherapy after multidisciplinary discussion and thorough patient information. For IA or IB grade 1 "patients" "no" adjuvant treatment after the surgery is suggested (www.sor-cancer.fr).

In addition, recent studies indicate that a proportion of these tumors (ovarian, tubal or peritoneal) arise from the distal fallopian tube. High grade PCFT and high grade OC may be the same disease. Previously, pathology analyses to distinguish between fallopian and ovarian tumors, even with advanced tumors, is often problematic. The shared immunophenotype suggests a common cell of origin in all categories, irrespective of site [19]. Jarboe et al. [20] suggested a two-pathway concept of ovarian carcinogenesis, underscoring molecular differences between low-grade and high-grade serous tumors of the ovary. The former initiates in the ovarian surface epithelium, mullerian inclusions, or endometriosis in the ovary. The latter arises from the endosalpinx and encompasses a subset of serous carcinomas. Criteria for distinguishing ovarian, tubal, and primary peritoneal serous carcinomas are tumor distribution and presence or absence of a precursor condition [21]. Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy in women with mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 has revealed that many early cancers in these women arise in the fallopian tube, specially the distal portion (fibrium). Recent studies that carefully examined the fallopian tubes suggest a high frequency of early ovarian or peritoneal serous carcinoma in patients (BRCA+ or BRCA-), meaning that some of these tumors have a fimbrial or tubal origin [19,21-23]. All our patient were BRCA 1-2 negative, and as there was no apparent pathology of the fallopian tube, one to two sections per tube was performed according to standard recommendations [24]. Therefore the fimbria was not exhaustively investigated [24].

Our study has several limitations. It is retrospective by nature, including patients managed before the paclitaxel era. The number of patients is quite small as a result of the drastic inclusion criteria. We have excluded many patients because of the lack of standardization of surgical practices and the impossibility to confirm histological type and grade of tumors at the time of slide review. We recognize the imbalance of the histological types in the PCFT and OC groups, and the unusual repartition of these histological tumors [25]. We have elected to accept a small but carefully defined group rather than a larger but heterogeneous one. Even though OC patients were matched on the basis of stage, grades were significantly lower in the OC group. Platinum based chemotherapy was given to 9 (81.8%) and 4 patients (13.8%) of the PCFT and OC patients, respectively, as a consequence of the higher occurrence of grade 2-3 in the study group. However, when grade and consequent adjuvant chemotherapy was taken into account, there does not seem to be any difference in outcome between the PCFT and OC groups.

However, given the rarity of these tumors, it is the first study which compare with drastic criteria inclusion outcomes for early stage (IA-IB) PCFT and OC in a matched, case-control comparison of selected cases. More patients were treated by chemotherapy in the PCFT group than in the OC group because of a higher proportion of grade 3 patients in the PCFT group, making it impossible to confirm that PCFT has a similar overall survival to OC. The surgical and adjuvant therapy management of fallopian tube carcinomas should mirror that of OC (Table 3).

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Overall survival estimated by groups: (A) overall population, (B) grade 2 and grade 3. Relapse-free survival estimated by groups: (C) overall population, (D) grade 2 and grade 3.

PCFT: primary carcinoma of the fallopian tube, OC: ovarian cancer, OS: overall survival, RFS: relapse-free survival.

|

Table 2

Characteristics of eight patients who developed a recurrence

PCFT: primary carcinoma of fallopian tube, CT: chemotherapy, APD: alive with persistent disease, AWD: alive without disease, OC: ovarian cancer, RT: radiation therapy.

*Interval evaluated between date of surgery and recurrence. †Interval evaluated between date of surgery and last follow-up news. ‡Death related to cancer. §Death related to other cause.

References

1. Nordin AJ. Primary carcinoma of the fallopian tube: a 20-year literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994. 49:349–361.

2. Trétarre B, Remontet L, Menegoz F, Mace-Lesec'h J, Grosclaude P, Buemi A, et al. Ovarian cancer: incidence and mortality in France. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2005. 34:154–161.

3. Baekelandt M, Jorunn Nesbakken A, Kristensen GB, Trope CG, Abeler VM. Carcinoma of the fallopian tube. Cancer. 2000. 89:2076–2084.

4. Moore KN, Moxley KM, Fader AN, Axtell AE, Rocconi RP, Abaid LN, et al. Serous fallopian tube carcinoma: a retrospective, multi-institutional case-control comparison to serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2007. 107:398–403.

5. Wethington SL, Herzog TJ, Seshan VE, Bansal N, Schiff PB, Burke WM, et al. Improved survival for fallopian tube cancer: a comparison of clinical characteristics and outcome for primary fallopian tube and ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2008. 113:3298–3306.

6. Deffieux X, Morice P, Thoury A, Camatte S, Duvillard P, Castaigne D. Pelvic and para-aortic lymphatic involvement in tubal carcinoma: topography and surgical implications. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2005. 33:23–28.

7. Tavassoli FA, Devilee P. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs (IARC WHO classification of tumours, No 4). 2003. Lyon: IARC Press.

8. Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Economopoulos T. Fallopian tube carcinoma: a review. Oncologist. 2006. 11:902–912.

9. Tamimi HK, Figge DC. Adenocarcinoma of the uterine tube: potential for lymph node metastases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981. 141:132–137.

10. Cormio G, Lissoni A, Maneo A, Marzola M, Gabriele A, Mangioni C. Lymph node involvement in primary carcinoma of the fallopian tube. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1996. 6:405–409.

11. di Re E, Grosso G, Raspagliesi F, Baiocchi G. Fallopian tube cancer: incidence and role of lymphatic spread. Gynecol Oncol. 1996. 62:199–202.

12. Leblanc E, Querleu D, Narducci F, Occelli B, Papageorgiou T, Sonoda Y. Laparoscopic restaging of early stage invasive adnexal tumors: a 10-year experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2004. 94:624–629.

13. Maxson WZ, Stehman FB, Ulbright TM, Sutton GP, Ehrlich CE. Primary carcinoma of the fallopian tube: evidence for activity of cisplatin combination therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 1987. 26:305–313.

14. Muntz HG, Tarraza HM, Goff BA, Granai GO, Rice LW, Nikrui N, et al. Combination chemotherapy in advanced adenocarcinoma of the fallopian tube. Gynecol Oncol. 1991. 40:268–273.

15. Morris M, Gershenson DM, Burke TW, Kavanagh JJ, Silva EG, Wharton JT. Treatment of fallopian tube carcinoma with cisplatin, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide. Obstet Gynecol. 1990. 76:1020–1024.

16. Barakat RR, Rubin SC, Saigo PE, Lewis JL Jr, Jones WB, Curtin JP. Second-look laparotomy in carcinoma of the fallopian tube. Obstet Gynecol. 1993. 82:748–751.

17. Peters WA 3rd, Andersen WA, Hopkins MP. Results of chemotherapy in advanced carcinoma of the fallopian tube. Cancer. 1989. 63:836–838.

18. Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Papaxoinis G, Andreadis C, Papatsibas G, Fountzilas G, et al. Primary fallopian tube carcinoma: results of a retrospective analysis of 64 patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2009. 115:97–101.

19. Roh MH, Kindelberger D, Crum CP. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and the dominant ovarian mass: clues to serous tumor origin? Am J Surg Pathol. 2009. 33:376–383.

20. Jarboe EA, Folkins AK, Drapkin R, Ince TA, Agoston ES, Crum CP. Tubal and ovarian pathways to pelvic epithelial cancer: a pathological perspective. Histopathology. 2008. 53:127–138.

21. Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, Hirsch MS, Feltmate C, Medeiros F, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007. 31:161–169.

22. Carlson JW, Miron A, Jarboe EA, Parast MM, Hirsch MS, Lee Y, et al. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: its potential role in primary peritoneal serous carcinoma and serous cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol. 2008. 26:4160–4165.

23. Crum CP, Drapkin R, Kindelberger D, Medeiros F, Miron A, Lee Y. Lessons from BRCA: the tubal fimbria emerges as an origin for pelvic serous cancer. Clin Med Res. 2007. 5:35–44.

24. Semmel DR, Folkins AK, Hirsch MS, Nucci MR, Crum CP. Intercepting early pelvic serous carcinoma by routine pathological examination of the fimbria. Mod Pathol. 2009. 22:985–988.

25. Deligdisch L, Penault-Llorca F, Schlosshauer P, Altchek A, Peiretti M, Nezhat F. Stage I ovarian carcinoma: different clinical pathologic patterns. Fertil Steril. 2007. 88:906–910.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download