Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the occurrence of residual or recurrent disease after conization for adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) of the uterine cervix.

Methods

Medical records of 99 patients with a histologically diagnosis of AIS of the uterine cervix by conization between 1991 and 2008 were reviewed retrospectively.

Results

Seventy eight of 99 patients (78.8%) had negative and 18 (18.2%) had positive resection margins of the conization specimen, and 3 (3.0%) had unknown margin status. Of the 78 patients with negative margins, 45 underwent subsequent hysterectomy and residual AIS were present in 4.4% (2/45) of patients. Ten of the 18 patients with positive margins received subsequent hysterectomy and 3 patients (30%) had residual AIS. Twenty-eight patients had conservative treatment and during the median follow-up time of 23.5 months (range, 7 to 124 months), only one patient (3.6%) had recurrent AIS and was treated with a simple hysterectomy. Eight patients became pregnant after conization, 4 of them delivered healthy babies, one had a spontaneous abortion and 3 were ongoing pregnancies.

Conclusion

Patients with positive resection margins after conization for AIS of the uterine cervix are significantly more likely to have residual disease. However, negative resection margin carries a lower risk for residual AIS, therefore conservative management with careful surveillance seems to be feasible in women who wish to preserve their fertility.

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) of the uterine cervix is thought to be the precursor of invasive adenocarcinoma. Many studies have shown that the incidence of AIS and cervical cancer has been increasing in women under the age of 35 years [1,2]. The increasing incidence of human papillomavirus 18 infection and increasing oral contraceptive uses are considered to be the main causes of this increasing incidence of AIS of the uterine cervix [3].

AIS of the uterine cervix presents a major clinical difficulty with regard to early detection by routine cytology or endocervical curettage (ECC), because it is multifocal and often found in the upper cervical canal, so that it may be missed during colposcopic examination [4,5]. Therefore, hysterectomy is considered as the standard treatment for AIS of the uterine cervix. However, controversy still remains because it often occurs in young aged patients who desire to preserve their fertility, and recent studies suggest that the majority of AIS of the uterine cervix is located around the squamocolumnar junction and most are unifocal [6,7].

Recently, conservative treatment with conization has been introduced as a treatment modality for AIS of the uterine cervix for patients who desire fertility preservation [6,8]. However, the risk of whether residual or recurrent disease exists after conization remains uncertain [9-12]. Even though negative resection margins after conization are considered as adequate management, there are reported risks of residual or recurrent diseases [12-15]. Therefore, long term follow-up after conization is suggested, although it is difficult to follow-up sufficiently after conization due to limited colposcopic findings and an increased incidence of cervical stenosis.

The aims of this study were to analyze the resection margin status on conization specimens to estimate residual or recurrent disease after conization, and to evaluate the safety of conization for the treatment of AIS of the uterine cervix.

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of patients with AIS of the uterine cervix who were diagnosed by conization at Cheil General Hospital and Women's Healthcare Center from January 1991 to December 2008. Ethical approval for reviewing the medical records of the patients was obtained from the Cheil General Hospital Ethics Committee, Korea.

Standard techniques of cold knife conization were utilized, and the depth and width of the conization was decided individually by the operating surgeon's experience based on the pictures of colposcopy. Then, additional endocervical margin resection was done with a right triangle-shaped electrode, and the bleeding site was cauterized with a round tip electrode. Sturmdorf suture was not used for bleeding control of the cold knife conization. Standard large loop excision of the transformation zone techniques were employed including at least one separate endocervical specimen obtained using the 1.0×1.0-cm loop.

The resection margin status, pathologic results of subsequent surgical specimens, and the results of the HPV test with Hybrid Capture II (Digene Co., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) or the MyHPV chip test (MyGene Co., Seoul, Korea) were thoroughly re-evaluated by two experienced pathologists.

When AIS involvement was noted at the boundary of cervical conization specimen, it was categorized as a positive resection margin, and when the involvement was within the cervical conization specimen, it was categorized as a negative resection margin. If the margin status was unclear because the data was not available or it was not documented in the report, the case was categorized as an unknown resection margin.

Subsequent surgical treatment after initial conization consisted of re-conization, simple hysterectomy, modified radical hysterectomy, and no further treatment after conization. Subsequent hysterectomy was carried out within three months of conization, and if it was not, it was considered as no further treatment after conization.

The pathologic results of subsequent surgical specimens were evaluated for comparison of residual AIS according to the resection margin status after conization. There was no patient who was subsequently diagnosed as invasive or microinvasive adenocarcinoma in the hysterectomy specimen after conization for AIS. A p-value of less than 0.05 was statistically significant by using Fisher's exact test. The follow-up period was defined as the time from the date of initial AIS diagnosis by conization to the last date of follow-up.

The median age of 99 patients who were treated by conization for AIS of the uterine cervix was 40 years (range, 23 to 66 years), and 32.3% were under the age of 35 years. The study population had a median gravidity of three and the median parity was two, and 16 (16.2%) were nulliparous. The result of the Papanicolaou (PAP) smear showed that one patient with a negative intraepithelial lesion, while 60 were squamous cell abnormalities including atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance, atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high-grade lesion, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, squamous cell carcinoma in situ and squamous cell carcinoma. Twenty eight patients showed glandular cell abnormalities including atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance, atypical endocervical cells, AIS, and adenocarcinoma. The remaining patients were referred after the biopsy procedure, and the initial PAP finding was not obtained. The median follow-up period was 31 months (range, 1 to 182 months), and most patients (90.9%) underwent cold knife conization rather than loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) for the initial diagnostic and therapeutic procedure (Table 1).

Pathologic findings of the conization specimens showed that many AIS cases were accompanied by other pathologic findings such as cervical dysplasia, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, adenosquamous carcinoma in situ, microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma, and microinvasive adenosquamous carcinoma of the uterine cervix. The most common pathologic finding of the conization specimen was AIS coexisting with squamous cell carcinoma in situ (42.4%), and the second most common was AIS only (30.3%) (Table 2).

Eighteen of 99 patients (18.2%) showed positive resection margins and 78 (78.8%) showed negative margins. Three patients (3.0%) had unknown margin status because they had underwent cervical conization at another hospital and there was no mention about the margin status on the pathologic reports, and they all underwent hysterectomy. Seven of 32 (21.9%) young aged patients under 35 years showed positive resection margins, and 11 of 67 (16.4%) older patients over 35 years had positive resection margins, and there was no statistical difference (p=0.162). Four of 18 patients with positive resection margins for AIS and 23 of 78 patients with negative resection margins did not receive any additional treatment. One patient with a positive resection margin for AIS underwent repeated cervical conization 3 months after the initial conization (Table 3).

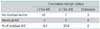

Table 4 shows the relation between the margin status of the conization specimens and the pathologic results of the hysterectomy specimens. After hysterectomy, 3 (30%) of 10 patients with positive resection margins for AIS had residual AIS, and 2 (4.4%) of 45 patients with negative resection margins had residual AIS. The difference in the incidence of residual AIS between patients with positive resection margins after conization and those with negative margins was statistically significant (p=0.037). Three patients with unknown resection margin status showed no residual AIS.

Twenty-eight patients were treated with cervical conization only, including one case of repeated cervical conization. The median follow-up period was 23.5 months (range, 7 to 124 months) and median age was 32.5 years (range, 23 to 55 years). Eight of 28 patients became pregnant after cervical conization, 4 resulted in successful full term deliveries, and 3 of them were currently pregnant. One patient had spontaneous abortion at 7th weeks of gestational age. Only one patient (3.6%) had recurrent AIS 47 months after the conization (Table 5).

The HPV testing was performed in 57 patients, and the results showed that the HPV type distribution of HPV 16 was 43.9% (25 patients), and that of HPV 18 was 22.8% (13 patients). Six patients (10.5%) showed other high risk types of HPV such as 31, 35, 45, 52, 56, 58, and 14 patients (24.6%) were not infected by HPV.

The AIS of the uterine cervix is a distinct histopathologic entity and many clinicians are struggling for the proper management. Recently, with the increase in conservative treatment, conization of the uterine cervix is gathering strength [3,6,7], Therefore, for adequate and secure management of patients with AIS, our study aimed at evaluating the safety of conization for the treatment of AIS of the uterine cervix, and recurrence rates according to the resection margin status of conization. Our study suggests that patients with negative resection margins after conization for cervical AIS, especially who wish to preserve their fertility, may be followed carefully with long-term surveillance and warning regarding the risks of residual or recurrent disease without hysterectomy. Patients with positive resection margins are more likely to have residual disease, therefore hysterectomy or a second conization may be required for these patients.

In our study, patients with positive resection margins had nearly nine times more residual disease than those with negative margins (30.0% vs. 4.4%). Previous studies reported that the incidence of residual disease in patients with negative margins after conization for AIS of the uterine cervix is low but not negligible [6,7,13,14]. Although the achievement of negative margins after conization has been described as an adequate treatment, the rates of recurrence and residual disease have been reported in up to 50% of cases [12-15]. However, recent findings suggest that AIS of the uterine cervix is located around the squamo-columnar junction and most tumors are unifocal, so that conservative management may be safe [6,7]. Our study is consistent with these recent findings and showed low residual disease in cases with negative resection margins after conization.

In the present study, of the 27 patients with no further treatment after conization and one repeated conization, only one patient had a recurrence after conization (3.6%). Our study suggest that recurrence and incidence of multifocal distribution of AIS is relatively low, however, the possibility of multifocal lesions are still not negligible.

The need for conservative management, especially for young patients with AIS who desire to preserve their fertility, is increasing because the incidence of AIS of the uterine cervix is increasing, especially in young women and conization as fertility-preserving treatment would be an attractive procedure for these patients [3]. In our study, 32 of 99 patients (32.3%) were under the age of 35, and 16 patients (16.2%) were nulliparous. Seven of 28 patients (25%) who were treated conservatively with conization achieved successful full term delivery or ongoing pregnancy. These results suggest that young patients with cervical AIS who wish to preserve their fertility may be treated effectively with conservative conization. However, conservative treatment of the patients with cervical AIS needs careful long-term surveillance and warning to patients regarding the risks of residual and recurrent disease, because several recent studies have reported recurrent invasive adenocarcinoma in patients with negative resection margins [7,14]. Therefore, clinicians should be aware that long-term follow-up is necessary for patients with cervical AIS after conization, regardless of the resection margin status. In the present study, the only patient who experienced recurrent AIS showed free resection margins after conization, and the recurrence was 47 months after the conization.

Although LEEP is a good therapeutic method for young patients who wish to preserve their fertility, cold knife conization has been regarded as a more adequate therapeutic method for patients with cervical AIS. Many studies have shown that patients who underwent cold knife conization for the initial procedure are less likely to have positive margins than those who were treated with LEEP [12,14]. It was reported that cold knife conization produces a greater volume and depth of specimen [16,17] and the risk of recurrence was also decreased [12], and therefore, cold knife conization was recommended as the adequate method over other therapeutic modalities in the AIS of the uterine cervix. However in our study, comparison of conization methods was not possible because 90.9% of all patients underwent cold knife conization (Table 1). Our institution primarily treats patients with cervical AIS by cold knife conization for the initial surgery, which is based on previous studies which recommend cold knife conization as the best therapeutic modality for cervical AIS, and this resulted in 90 of 99 patients being treated by cold knife conization. In our institution, after cold knife conization, additional endocervical margin resection is done with a right triangle-shaped electrode, and then the bleeding site is cauterized with a round tip electrode. The reason for the low residual and recurrent AIS in our study is that this procedure removes residual AIS at the deep site of the endocervical area. However, some studies have observed that LEEP is technically easier and more rapid than cold knife conization [18]. Additionally, LEEP showed a favorable postoperative morbidity rate and a comparable success rate in some studies, and therefore, LEEP has been reported as a comparable treatment modality for cervical AIS [16,19]. In some reports, laser conization showed less or equivalent rates of negative margins over cold knife conization but larger volume of excision was possible than LEEP [13,20,21]. Further large prospective studies would make it possible to evaluate a more effective and safer therapeutic modality of AIS of the uterine cervix.

The infection rate of HPV 16 and 18 were noted as 43.9% and 22.8%, respectively, among 57 patients in whom the HPV testing was performed in our study. Bosch et al. [22] reported 48.4% HPV 16 and 36.3% HPV 18 infection rates in their review article, and our results shows lower rates of HPV 16 and 18 infections compared to the above data, especially with HPV 18 infection. Some authors [23] have reported that AIS of the uterine cervix is more specific for HPV 18 infection, however, our study showed that rate of HPV 16 infection is higher than that of HPV 18 because patients with AIS coexisting squamous lesions is higher than those with AIS alone. The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology 2006 consensus guidelines recommend repeated evaluation using repeated cervical cytology, HPV DNA testing, and colposcopy with endocervical curettage [24]. The high risk HPV status before or after conization may be helpful to predict recurrence of AIS after conservative management. Further studies on HPV type distribution in cervical AIS in Korean population would be helpful for the better understanding of cervical AIS.

In conclusion, hysterectomy should be considered for patients with a diagnosis of AIS who do not want to preserve their fertility. However, patients with negative resection margins after conization for cervical AIS, especially who wish to preserve their fertility, may be followed carefully with long-term surveillance and warning regarding the risks of residual or recurrent disease without hysterectomy. Patients with positive resection margins are more likely to have residual disease, so hysterectomy or a second conization to achieve negative margins may also be required.

Figures and Tables

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A102065-25, Tae Jin Kim).

Notes

References

1. Sherman ME, Wang SS, Carreon J, Devesa SS. Mortality trends for cervical squamous and adenocarcinoma in the United States. Relation to incidence and survival. Cancer. 2005. 103:1258–1264.

2. Han CH, Cho HJ, Lee SJ, Bae JH, Bae SN, Namkoong SE, et al. The increasing frequency of cervical cancer in Korean women under 35. Cancer Res Treat. 2008. 40:1–5.

3. Madeleine MM, Daling JR, Schwartz SM, Shera K, McKnight B, Carter JJ, et al. Human papillomavirus and long-term oral contraceptive use increase the risk of adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001. 10:171–177.

4. Christopherson WM, Nealon N, Gray LA Sr. Noninvasive precursor lesions of adenocarcinoma and mixed adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Cancer. 1979. 44:975–983.

5. Kim WS, Lee TS. Adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix. Korean J Gynecol Oncol Colposc. 1998. 9:140–143.

6. Kim JH, Park JY, Kim DY, Kim YM, Kim YT, Nam JH. The role of loop electrosurgical excisional procedure in the management of adenocarcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009. 145:100–103.

7. Costa S, Negri G, Sideri M, Santini D, Martinelli G, Venturoli S, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) test and PAP smear as predictors of outcome in conservatively treated adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2007. 106:170–176.

8. Salani R, Puri I, Bristow RE. Adenocarcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix: a metaanalysis of 1278 patients evaluating the predictive value of conization margin status. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009. 200:182.e1–182.e5.

9. McHale MT, Le TD, Burger RA, Gu M, Rutgers JL, Monk BJ. Fertility sparing treatment for in situ and early invasive adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 98:726–731.

10. Ostor AG, Duncan A, Quinn M, Rome R. Adenocarcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix: an experience with 100 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2000. 79:207–210.

11. Shin CH, Schorge JO, Lee KR, Sheets EE. Conservative management of adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2000. 79:6–10.

12. Kennedy AW, Biscotti CV. Further study of the management of cervical adenocarcinoma in situ. Gynecol Oncol. 2002. 86:361–364.

13. Soutter WP, Haidopoulos D, Gornall RJ, McIndoe GA, Fox J, Mason WP, et al. Is conservative treatment for adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix safe? BJOG. 2001. 108:1184–1189.

14. Young JL, Jazaeri AA, Lachance JA, Stoler MH, Irvin WP, Rice LW, et al. Cervical adenocarcinoma in situ: the predictive value of conization margin status. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 197:195.e1–195.e7.

15. Dalrymple C, Valmadre S, Cook A, Atkinson K, Carter J, Houghton CR, et al. Cold knife versus laser cone biopsy for adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix: a comparison of management and outcome. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008. 18:116–120.

16. Girardi F, Heydarfadai M, Koroschetz F, Pickel H, Winter R. Cold-knife conization versus loop excision: histopathologic and clinical results of a randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol. 1994. 55:368–370.

17. Mathevet P, Dargent D, Roy M, Beau G. A randomized prospective study comparing three techniques of conization: cold knife, laser, and LEEP. Gynecol Oncol. 1994. 54:175–179.

18. Wright TC Jr, Gagnon S, Richart RM, Ferenczy A. Treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia using the loop electrosurgical excision procedure. Obstet Gynecol. 1992. 79:173–178.

19. Giacalone PL, Laffargue F, Aligier N, Roger P, Combecal J, Daures JP. Randomized study comparing two techniques of conization: cold knife versus loop excision. Gynecol Oncol. 1999. 75:356–360.

20. Andersen ES, Nielsen K. Adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix: a prospective study of conization as definitive treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2002. 86:365–369.

21. Phadnis SV, Atilade A, Young MP, Evans H, Walker PG. The volume perspective: a comparison of two excisional treatments for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (laser versus LLETZ). BJOG. 2010. 117:615–619.

22. Bosch FX, Burchell AN, Schiffman M, Giuliano AR, de Sanjose S, Bruni L, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections and type-specific implications in cervical neoplasia. Vaccine. 2008. 26:Suppl 10. K1–K16.

23. Park JY, Bae J, Lim MC, Lim SY, Lee DO, Kang S, et al. Role of high risk-human papilloma virus test in the follow-up of patients who underwent conization of the cervix for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Gynecol Oncol. 2009. 20:86–90.

24. Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D, et al. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007. 11:223–239.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download