Abstract

Objective

Possible reasons for hysterectomy in the initial surgical management of advanced invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) might be a high frequency of uterine involvement and its impact on survival. The aim of the present study was to describe the frequency of uterine involvement and its association with survival in an unselected population of EOC patients who underwent hysterectomy.

Methods

All incident cases of EOC diagnosed in Israeli Jewish women between March 1994 to June 1999, were identified within the framework of a nationwide case-control epidemiological study. The target population of the present report includes all stage II-IV EOC patients who had a uterus at the time of diagnosis. Of the 822 such patients, 695 fulfilled the inclusion criterion. Excluded were 141 patients for various reasons. The present analysis is based on the remaining 554 patients.

Results

Uterine involvement was present in 291 (52.5%) of the patients and it was macroscopic in only 78 (14.1%). The serosa was the most common site of isolated metastases. Multivariate analysis showed that advanced stage significantly increased the risk for uterine involvement. The overall median survival with any uterine involvement was significantly lower compared to those with no involvement (38.9 months vs. 58.0 months; p<0.001).

Conclusion

There is an association between uterine involvement, whether macro- or microscopic, and lower survival even after hysterectomy although residual tumor could not be included in the analysis. Further studies are required to establish whether uterine involvement itself is an unfavorable risk factor or merely a marker of other unfavorable prognostic factors.

The routine initial surgical management of advanced invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC), includes hysterectomy.1-4 However, to the best of our knowledge, the rationale for hysterectomy at the initial operation is not clear. Possible reasons might be a high frequency of uterine involvement by the tumor and its potential impact on survival.

Considering the sparse data regarding these issues, we undertook this study to describe the frequency of uterine involvement and its association with survival in an unselected population of EOC patients who underwent hysterectomy.

All incident cases of histological confirmed cancer of the ovary (International Classification of Disease [ICD]-9th Revision 183), diagnosed in Israeli Jewish women between March 1 1994, and June 30 1999, were identified within the framework of a nationwide case-control epidemiological study. The study received the approval of the Institutional Review Board and Ministry of Health. Specific details on the methodology of this study were given in a previous publication.5 The data base contains 1,036 EOC patients. The target population of the present retrospective report includes all stage II-IV EOC patients identified in the study who had a uterus at the time of diagnosis. Of the total group of 822 stage II-IV epithelial ovarian carcinoma patients 695 fulfilled the inclusion criterion.

Excluded from the study were 141 patients: 15 that did not undergo hysterectomy, 52 that received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and therefore original uterine involvement could not be assessed, and 74 with missing pathology reports. The present analysis is thus based on the remaining 554 patients.

The histological diagnosis of ovarian carcinoma was based on the original routine pathology report. Clinical characteristics were abstracted from medical records. The presence of uterine involvement was based on surgical and pathological reports. During the pathological examination of the excised uterine specimen at least 2 sections from the cervix and 4 sections from the uterine body were usually done. In all patients with macroscopic disease on the uterine surface, the finding was confirmed histologically. Survival data were obtained from the Central Population Registry using the personal identification number that is being assigned to all citizens upon birth or immigration.

Comparisons of selected characteristics by the presence of uterine involvement were made using the chi-square test for categorical variables and an impaired t-test for continuous variables.

Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Median survival time with its respective 95% confidence intervals were derived according to the presence and the type of uterine involvement and compared using the logrank test. The association of selected clinical characteristics and the presence and type of uterine involvement was assessed through multivariate logistic regression models.

The mean age of the study group was 58 years (range, 23 to 87 years). Selected clinico-pathological characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 80% of the patients had stage III disease; two thirds had serous type and high grade disease tumors. About half of the patients had histological confirmed macroscopic or microscopic uterine involvement.

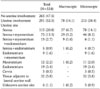

Table 2 presents uterine involvement according to type (macroscopic, microscopic) and by uterine site. Macroscopic uterine involvement was present in 14.1% of the patients. Serosal involvement, with or without involvement of other uterine sites, was present in 210 (37.9%) patients (macroscopic 13.7% and microscopic 24.2%). Isolated serosal involvement was present in 115 (20.8%) patients and it was macroscopic in 37 (6.7%) patients. Isolated involvement of other sites was less common. Coexisting endometrial involvement with or without involvement of other uterine sites was present in 48 (8.7%) patients.

Table 3 presents the distribution of selected demographic and tumor related characteristics by presence of uterine involvement. Uterine involvement was statistically significantly higher in patients with stage III, IV tumors and in those with serous type tumors compared to those with stage II tumors and those with other types of tumors (p<0.001 and p=0.05, respectively). Age and grade did not affect the frequency of any type of uterine involvement.

A multivariate logistic regression model with any uterine involvement as the dependent variable showed that stages III and IV significantly increased the risk for uterine involvement (5 and 10 folds respectively) controlling for age, grade and histological type. Serous type tumors increased the risk by about 40% (p=0.06) compared to other types (Table 4). Similar results were found when analyzing the microscopic involvement group versus no uterine involvement. A non significant twofold increased risk for macroscopic uterine involvement among women with stage IV compared to those with stage III when adjusted for age, grade and histological type (p=0.08) was found (data not shown).

The effect of uterine involvement on survival in patients who underwent hysterectomy is presented in Table 5. The overall median survival with any uterine involvement was significantly lower compared to those with no involvement (38.9 months vs. 58.0 months; p<0.001). The overall median survival of patients with microscopic involvement was higher than of those with macroscopic involvement (41.2 months vs. 37.2 months) however this difference was not significant.

Data regarding uterine involvement in ovarian carcinoma are very scarce and are also not mentioned in the many reviews dealing with the surgical management of EOC.1-4 In most autopsy reports from the last 3 decades that deal with the metastatic pattern of EOC the uterus is not listed as a metastatic site6-10 probably because the patients underwent a hysterectomy before they died of the disease. In only one study of 100 autopsies of ovarian cancer11 it is reported that the uterine serosa, the myometrium and the cervix were involved in 27%, 10%, and 3% respectively. No further details regarding macro- or microscopic involvement are given.

Several reasons for hysterectomy in EOC may be offered. One is that the uterus is a frequent site of metastasis and therefore it should be removed as part of cytoreductive surgery. According to the FIGO 25th annual report12 the frequency of stage IIa EOC, defined as extension and/or metastases to the uterus and/or tubes, among 4,004 patients diagnosed from 1996 to 1998, was only 1.8%. However the frequency of uterine involvement alone is not specified in this report. Nevertheless this percentage is of the same magnitude as our assessment of 2.2% (12/554) of stage II patients with uterine involvement.

Our data indicate that overall uterine involvement in EOC patients is present in 52.5% of the patients that underwent hysterectomy and that it was macroscopic in only 14.1% of them. In multivariate analysis (including age, stage, grade, and histological type), stage remained the only factor significantly affecting the presence of uterine involvement. Regretfully, other prognostic factors, such as residual disease, preoperative CA125 levels and volume of ascites, could not be analyzed because of lack of data in more than half of the patients. Isolated myometrial and cervical metastasis were observed by us in only 2.1% and 0.5% of the patients respectively. The infrequent occurrence of cervical metastasis from EOC has already been previously reported in several small series.13-18

The coexistence of ovarian and endometrial carcinoma, considered to be present in about 3-10% of EOC patients,19,20 can be considered as another reason for hysterectomy. These findings are in line with our results showing coexistence in 8.7% of the patients. Such coexistence can be readily ascertained by appropriate preoperative work-up such as cytological assessment, sonographic evaluation and/or biopsy of the endometrium.

The argument that hysterectomy should be done because the retained uterus may interfere with clinical follow-up assessment of pelvic recurrence. Since the advent of serological markers and modern sophisticated imaging procedures such as transvaginal sonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography this argument is of less importance. An additional argument for hysterectomy can be that the uterus is an unnecessary organ at the age most of the patients are diagnosed and that the procedure does not increase the complication rate. At present, stricter indications for organ excision are usually required and this argument seems to be obsolete. Extension of any procedure without an appropriate indication seems unnecessary.

The postoperative presence of minimal or no residual disease is considered to be a very important prognostic indicator in EOC.21-23 However, it has never been established whether optimal cytoreduction is a function of surgical skill or a function of inherent biological properties of the tumor that make optimal cytoreduction possible.24-27 If optimal cytoreduction has indeed a favorable effect on outcome, and hysterectomy assists in achieving it, than it is certainly justified.

Obviously the main argument for hysterectomy is its possible impact on survival. Our data indicate that among patients who underwent hysterectomy the median survival of those with uterine involvement, whether macro- or microscopic, was significantly lower than that of those with no uterine involvement (38.9 vs. 58.0 months, p<0.001).

In a relatively large proportion of our advanced EOC patients with uterine involvement it consisted mainly of microscopic serosal involvement. This may be taken to indicate that other peritoneal serosal surfaces are microscopically involved as well. Although theoretically improvement of survival can be expected if all microscopic metastases were removed, the therapeutic value of removal of microscopic residual disease as part of the concept of cytoreduction is uncertain. Nevertheless our data indicate that even microscopic uterine involvement is associated with a lower survival. Whether microscopic uterine involvement is an independent risk factor or merely a marker of other unfavorable prognostic factors, is unclear.

The strength of our study is the relatively large number of consecutive stage II-IV patients derived from a population database. The weaknesses of our study are the limitations inherent in its retrospective nature. Thus, the presence of uterine involvement was based on the original routine pathology report potentially introducing a significant bias to detect uterine metastasis due to different number of section performed according to the policy of various institutions and pathologists.

The design of the present study cannot determine the impact of uterine involvement on survival of advanced EOC patients, nor can it assess the optimal surgical management of these patients with regard to hysterectomy. However, our study shows that the frequency of macroscopic uterine involvement is low and that there is an association between uterine involvement, whether macro- or microscopic, and survival even after hysterectomy.

The therapeutic value of routine hysterectomy at the initial operation for EOC should be further investigated. The optimal study to address the contribution of hysterectomy to survival should be a randomized clinical trial that would be difficult to perform due to ethical considerations.

Figures and Tables

Table 2

Uterine involvement according to type (macroscopic, microscopic) and by uterine site of the study group

Table 3

Distribution of selected demographic and tumor related characteristics by presence of uterine involvement

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The members of the National Israel Ovarian Cancer Group are as follows:

Shmuel Anderman, MD, Marco Alteras, MD, Shaul Anteby, MD, Jack Atad, MD, Amiram Avni, MD, Amiram Bar-Am, MD, Dan Beck, MD, Uziel Beller, MD, Gilad Ben-Baruch, MD, Yehuda Ben-David, MD, Izhar Ben-Shlomo, MD, Haim Biran, MD, Moshe Ben Ami, MD, Angela Chetrit, BSc, Shlomit Cohen, MD, Shulamit Cohen, MD, Ram Dgani, MD, Yehudit Fishler, MD, Ami Fishman, MD, Eitan Friedman, MD, Ofer Gemer, MD, Ruth Gershoni, MD, Reuvit Halperin, MD, Galit Hirsh-Yechezkel, MD, David Idelman, MD, Rafael Katan, MD, Yuri Kopilovic, MD, Efrat Lahad, MD, Liat Lerner-Geva, MD, Hanoch Levavi, MD, Tally Levi, MD, Albert Levit, MD, Beatriz Lifschitz-Mercer, MD, Flora Lubin, MSc, RD, Zohar Leviatan, MD, Jacob Marcovich, MD, Joseph Menczer, MD, Baruch Modan, MD (Chairman, deceased), Hedva Nitzan, RN, MPH, Moshe Oetinger, MD, Tamar Perez, MD, Benjamin Piura, MD, Siegal Sadetzki, MD, David Schneider, MD, Mariana Shteiner, MD, Zion Tal, MD, Chaim Yaffe, MD, Ilana Yanai, MD, Shifra Zohar, RN

References

1. Marsden DE, Friedlander M, Hacker NF. Current management of epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a review. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000. 19:11–19.

2. Trope C, Kaern J. Primary surgery for ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006. 32:844–852.

3. Leitao MM Jr, Chi DS. Operative management of primary epithelial ovarian cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007. 9:478–484.

4. Fader AN, Rose PG. Role of surgery in ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007. 25:2873–2883.

5. Modan B, Hartge P, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, Chetrit A, Lubin F, Beller U, et al. Parity, oral contraceptives, and the risk of ovarian cancer among carriers and noncarriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2001. 345:235–240.

6. Julian CG, Goss J, Blanchard K, Woodruff JD. Biologic behavior of primary ovarian malignancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1974. 44:873–884.

7. Rose PG, Piver MS, Tsukada Y, Lau TS. Metastatic patterns in histologic variants of ovarian cancer: an autopsy study. Cancer. 1989. 64:1508–1513.

8. Reed E, Zerbe CS, Brawley OW, Bicher A, Steinberg SM. Analysis of autopsy evaluations of ovarian cancer patients treated at the National Cancer Institute, 1972-1988. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000. 23:107–116.

9. Hess KR, Varadhachary GR, Taylor SH, Wei W, Raber MN, Lenzi R, et al. Metastatic patterns in adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2006. 106:1624–1633.

10. Guth U, Huang DJ, Bauer G, Stieger M, Wight E, Singer G. Metastatic patterns at autopsy in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2007. 110:1272–1280.

11. Dvoretsky PM, Richards KA, Angel C, Rabinowitz L, Stoler MH, Beecham JB, et al. Distribution of disease at autopsy in 100 women with ovarian cancer. Hum Pathol. 1988. 19:57–63.

12. Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Beller U, Benedet JL, Creasman WT, et al. Carcinoma of the ovary. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003. 83:Suppl 1. 135–166.

13. McComas BC, Farnum JB, Donaldson RC. Ovarian carcinoma presenting as a cervical metastasis. Obstet Gynecol. 1984. 63:593–596.

14. Mazur MT, Hsueh S, Gersell DJ. Metastases to the female genital tract: analysis of 325 cases. Cancer. 1984. 53:1978–1984.

15. Lemoine NR, Hall PA. Epithelial tumors metastatic to the uterine cervix: a study of 33 cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1986. 57:2002–2005.

16. Lyon DS, Kaminski PF, Wheelock JB. Significance of a positive Papanicolaou smear in a well screened population. South Med J. 1989. 82:190–192.

17. Guidozzi F, Sonnendecker EW, Wright C. Ovarian cancer with metastatic deposits in the cervix, vagina, or vulva preceding primary cytoreductive surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 1993. 49:225–228.

18. Tarraza HM, Muntz HG, De Cain M, Jones MA. Cervical metastases in advanced ovarian malignancies. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1993. 14:274–278.

19. Zaino R, Whitney C, Brady MF, DeGeest K, Burger RA, Buller RE. Simultaneously detected endometrial and ovarian carcinomas: a prospective clinicopathologic study of 74 cases: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2001. 83:355–362.

20. Williams MG, Bandera EV, Demissie K, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L. Synchronous primary ovarian and endometrial cancers: a population-based assessment of survival. Obstet Gynecol. 2009. 113:783–789.

21. Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002. 20:1248–1259.

22. Memarzadeh S, Berek JS. Advances in the management of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Reprod Med. 2001. 46:621–629.

23. Eisenkop SM, Spirtos NM, Friedman RL, Lin WC, Pisani AL, Perticucci S. Relative influences of tumor volume before surgery and the cytoreductive outcome on survival for patients with advanced ovarian cancer: a prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 2003. 90:390–396.

24. Heintz AP. Surgery in advanced ovarian carcinoma: is there proof to show the benefit? Eur J Surg Oncol. 1988. 14:91–99.

25. Covens AL. A critique of surgical cytoreduction in advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000. 78:269–274.

26. Menczer J. Cytoreductive surgery in the treatment of advanced ovarian carcinoma: some controversial aspects. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1992. 13:246–255.

27. Hunter RW, Alexander ND, Soutter WP. Meta-analysis of surgery in advanced ovarian carcinoma: is maximum cytoreductive surgery an independent determinant of prognosis? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992. 166:504–511.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download