Abstract

Objective

Recently, a symptom index for identification of ovarian cancer, based on specific symptoms along with their frequency and duration, was proposed. The current study aimed at validation of this index in Korean population.

Methods

A case-control study of 116 women with epithelial ovarian cancer and 209 control women was conducted using questionnaires on eight symptoms. These included pelvic/abdominal pain, urinary urgency/frequency, increased abdominal size/bloating, difficulty eating/feeling full. The symptom index was considered positive if any of the 8 symptoms present for <1 year that occurred >12 times per month. The symptoms were compared between ovarian cancer group and control group using chi-square test. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether the index predicted cancer. Sensitivity and specificity of the symptom index were also determined.

Results

The symptom index was positive in 65.5% of women with ovarian cancer, in 31.1% of women with benign cysts, and in 6.7% of women on routine screening (ps<0.001). Significantly higher proportion of ovarian cancer patients were positive for each symptom as compared with control group (ps<0.001). Results from the logistic regression indicated that the symptom index independently predicted cancer (p<0.001; OR, 10.51; 95% CI, 6.14 to 17.98). Overall, the sensitivity and specificity of the symptom index were 65.5% and 84.7%, respectively. Analyses of sensitivity by stage showed that the index was positive in 44.8% of patients with stage I/II disease and in 72.9% of patients with stage III/IV disease.

Ovarian cancer is the second most common gynecologic malignancy worldwide and, unfortunately, the mortality rate is also high.1 One of the reasons for the high fatality rate is that more than two-thirds of ovarian cancer cases are diagnosed with advanced-stage disease. Five-year survival rates of advancedstage disease are only 20% to 30%, whereas those for early stage disease are 70% to 90%. To improve the survival, several attempts to develop screening strategies to diagnose ovarian cancer in earlier stage have been made. However, available screening tools, CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasound, have not shown to be sensitive and specific enough to recommend for the general population.

Due to the current limitations of screening, several investigators have tried to identify specific symptoms as a potential method for early detection of the disease.2-5 Studies of symptoms have confirmed that women with ovarian cancer have gastrointestinal, abdominal, and urinary symptoms. Such symptoms are often vague, and many false positive results may occur. But, Goff et al.6 advocated that symptoms are more recent and greater in severity and frequency in women with ovarian cancer than in those without. Moreover, the authors suggested a symptom index composed of six symptoms along with their frequency and duration to be useful for identifying women at risk.7 However, the symptom index has not been validated in an independent patient cohort. The aim of this study was to validate the symptom index in Korean population.

From July 2007 through February 2008, a symptom survey of women who visited the gynecologic oncology department in our hospital was carried out using questionnaires based on symptoms of the ovarian cancer symptom index suggested by Goff et al. Participants included women who were diagnosed to have ovarian cancer (cancer group), women who underwent surgery for benign ovarian cysts (benign cyst group), and women who visited our department for routine Pap smear with at least one intact ovary and uterus (clinic group). From clinic group, women who had history of gynecologic malignancies were excluded. Both ovarian cancer group and benign cyst group were histologically confirmed. Benign cyst group and clinic group constituted the control group.

All participants were asked to complete an identical questionnaire about the occurrence of 8 symptoms, which included pelvic/abdominal pain, urinary urgency/frequency, increased abdominal size/bloating, and difficulty eating/feeling full, along with the frequency and duration of symptoms. A symptom index was considered positive if a woman had any of the 8 symptoms present for <1 year that occurred >12 times per month. We included eight symptoms in this survey, which added urinary symptoms to Goff's original symptom index. Urinary symptoms were deleted from Goff's index in selection of the most sensitive model. However, we included urinary symptoms which have been suggested to be significantly related to ovarian cancer in several studies as well as Goff's study. In benign cyst group, surveys were done before operation. Whereas, in ovarian cancer group, surveys were done during hospital stays for operation or for chemotherapy. Participants were instructed to fill out the questionnaire by themselves. But, in case participants could not understand the questions fully, investigators were allowed to explain them.

Preoperative CA-125 level was assessed in almost all patients in ovarian cancer and benign cyst group. In our institution, the cut-off value for CA-125 level is 37 U/ml. When analyzing the combination of CA-125 test and symptom index, it was considered suggestive of ovarian cancer if either CA-125 test or symptom index was positive.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The symptoms were compared between the patient groups using chi-square test. When the questionnaire was not filled completely, the unanswered variable was processed into missing value. Odds ratios (ORs) of each symptom variable for ovarian cancer were calculated by logistic regression analysis. In addition, a multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine which of the four symptoms would remain independently significant. Sensitivity and specificity of the symptom index were also determined. For all analyses, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Three hundred and twenty-five women participated in this survey. Participants were composed of 116 women with ovarian cancer, 74 women with benign ovarian cysts, and 135 women on routine Pap smear. Median ages of ovarian cancer, benign cyst, and routine screening patients were 54, 35.5, and 51 years, respectively (Table 1). Two-thirds of ovarian cancer patients had advanced diseases (III 55.3%; IV 19.3%). In benign cyst group, endometriotic cyst was the most frequent diagnosis (45.9%) followed by teratoma (29.7%).

In ovarian cancer group, the median time from diagnosis to interview was 3.17 months (range, -3 to 84 months), and 66% were interviewed within 6 months. Because some patients were surveyed years after the diagnosis, we analyzed the symptoms separately for those diagnosed within 6 months and those diagnosed >6 months from the survey to determine whether the data were affected by significant recall bias. There was not a significant difference in the rates of positive index between the two groups of cancer patients (p=0.169).

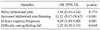

Seventy-six ovarian cancer patients (76/116, 65.5%) had a positive symptom index, whereas the index was positive in 23 benign cyst patients (23/74, 31.1%) and 9 routine screening patients (9/135, 6.7%) (ps<0.001, Table 2). For each symptom, significantly higher proportion of ovarian cancer patients were positive as compared with clinic group (ps<0.001) (Table 2). When we compared the symptoms between cancer and benign cyst group, symptoms were significantly more prevalent in cancer patients, except pelvic/abdominal pain (17.2% in cancer vs. 13.5% in benign cyst group; p=0.492). The high prevalence of endometriotic cyst may explain the frequency of pelvic/abdominal pain in benign cyst group.

Results from the logistic regression indicated that the symptom index independently predicted cancer (p<0.001; OR, 10.51; 95% CI, 6.14 to 17.98). When analyzed four symptom variables separately, increased abdominal size/bloating and urinary urgency/frequency were statistically significant predictors of ovarian cancer (Table 3). After multivariate analysis, the two symptom variables remained independently significant (Table 4). In particular, urinary symptom was a significant predictor in our study, which was not included in the symptom index of Goff et al. in selecting the model with the greatest sensitivity. In our study, however, the sensitivity decreased from 65.5% to 56.9% with a similar specificity of 87.6% using the symptom index composed of 6 symptoms without urinary symptoms. This can be said that urinary symptom was more frequently reported by ovarian cancer patients in Korean population.

Overall, the sensitivity and specificity of the symptom index were 65.5% and 84.7%, respectively. This result was comparable to that of the study of Goff et al. Analyses of sensitivity by stage showed that the index was positive in 44.8% of patients with stage I/II disease and in 72.9% of patients with stage III/IV disease. When stratified by age, the sensitivity was 81.9% with a specificity of 58.5% for women aged <50 years. For women aged ≥50 years, the sensitivity was 69.3% and the specificity was 89.0%.

When we combined CA-125 level and symptom index, the sensitivity rose to 85.3% while the specificity decreased to 59.5%. In ovarian cancer patients who did not have elevated CA-125 levels, 5 out of 11 cases (45.5%) were additionally identified with the symptom index. Unfortunately, 30.5% (18/59 patients) of benign cyst patients with normal CA-125 levels also demonstrated a positive symptom index score.

The current study supported previous studies suggesting that specific symptoms were useful in identifying women with ovarian cancer.2-5,8 In addition, this study validated the ovarian cancer symptom index developed by Goff et al. in Korean population. The sensitivity and the specificity of the symptom index in our study were 65.5% and 84.7%, respectively. This was consistent with the findings of Goff's study. In addition, the symptom index was comparable to CA-125 test, which has sensitivity that ranges from 50% to 79% and specificity that ranges from 96% to 99%.9,10

Researches on specific symptoms for early detection of ovarian cancer started from the limitations of available screening strategies, such as CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasonography. Although a UK pilot study in 199911 showed a survival benefit for screening using CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasonography, there has been no confirmatory result to support routine screening for the general population. The final results of UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) will not be known until 2014.12 Consequently, until there is a valid screening tool, several researchers suggested that symptoms associated with ovarian cancer may serve as another option for early detection. In several retrospective studies, more than 90% of women with ovarian cancer do have at least one symptom.2-6 The symptoms most commonly seen are abdominal or gastrointestinal in nature, whereas gynecologic symptoms, such as abnormal vaginal bleeding or menstrual irregularities, were reported by less than 25% of patients.5,13,14

These symptoms tend to be more constant and of more recent onset. With accumulating evidences, finally in 2007, several US organizations, including patient groups, released a consensus statement on the symptoms of ovarian cancer.15 The statement urges women to seek medical attention if they have new and persistent symptoms of bloating, pelvic or abdominal pain, difficulty eating or early satiety, and urinary urgency or frequency. Recently, it was further supported by Hamilton et al who reported that these symptoms are also independently associated with ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care similarly to hospital series.16

In this context, Goff et al. developed an ovarian cancer symptom index including 6 symptoms (pelvic/abdominal pain, increased abdominal size/bloating, and feeling full/difficulty eating) to implement widespread awareness of ovarian cancer symptoms and are currently in the process of examining the index in a prospective fashion in a primary care setting.7 They advocated that this tool can be useful in early detection of ovarian cancer and that, through diagnosing cancer 3 to 6 months earlier, the symptom index might be able to favorably affect the survival. However, caution should be paid about the view of potential survival benefit from early detection through recognizing those symptoms. There have been several studies refuting the suggestion that delay in diagnosis is responsible for the advanced disease.2,13,17,18 In these studies, women with early stage disease reported similar or rather longer duration of symptoms, indicating there may be significant biological differences between the early and advanced stages. Nevertheless, Goff's symptom index is meaningful in that it made patients and clinicians aware of specific symptoms as early alarm.

When combining CA-125 and symptom index, the sensitivity increased from 65.5% to 85.3% in our study. Unfortunately, however, the specificity of the combination test dropped to 59.5%. Although we only included women who received operations for cancer or benign cyst in this analysis, our result was similar to the study of Andersen et al.19 In spite of the low specificity of the combination of CA-125 and symptom index, this strategy is worthy of further research in larger population because high sensitivity is critical in first-line screening. In addition, using transvaginal ultrasonography as a second-stage test, false positive findings can be identified before referral for surgery, achieving adequate positive predictive value. A potential limitation of our study is recall bias, even though there was not a significant difference in response between the patients diagnosed within 6 months and those diagnosed >6 months from the survey. Although we tried to survey patients as early as possible from diagnosis, the majority of ovarian cancer patients were interviewed after surgery and during the courses of chemotherapy. However, this study is meaningful in that symptoms were directly obtained from patients, not from medical records. Recall bias can be resolved only in subsequent prospective studies. Another limitation of this study is that this survey was conducted in a secondary care setting. To overcome this limitation, we included women who visited the general gynecology subdivision in the gynecologic oncology department for routine Pap smear in the clinic group. Although these women may represent the women in primary care settings to some extent, following validation studies in primary care settings are still needed. In addition, the discrepancy in age distribution between the three groups might affect the results of this study.

The symptom index is not sufficient to be recommended as a screening tool as yet. However, when the patients complain about recent and persistent abdominal, gastrointestinal or urinary symptoms, it is important for attending physicians to have a suspicion and to perform pelvic examinations. Pelvic examinations do not add to the medical costs, and transvaginal ultrasonography, when needed, does not cause significant discomforts to patients. Until there is a valid screening test, the symptom index may serve as a useful and inexpensive tool to identify patients who need further evaluations. In future studies, the utility of these symptoms in general population needs to be evaluated in prospective settings.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005. 55:74–108.

2. Olson SH, Mignone L, Nakraseive C, Caputo TA, Barakat RR, Harlap S. Symptoms of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 98:212–217.

3. Vine MF, Calingaert B, Berchuck A, Schildkraut JM. Characterization of prediagnostic symptoms among primary epithelial ovarian cancer cases and controls. Gynecol Oncol. 2003. 90:75–82.

4. Smith EM, Anderson B. The effects of symptoms and delay in seeking diagnosis on stage of disease at diagnosis among women with cancers of the ovary. Cancer. 1985. 56:2727–2732.

5. Yawn BP, Barrette BA, Wollan PC. Ovarian cancer: the neglected diagnosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004. 79:1277–1282.

6. Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, Muntz HG. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004. 291:2705–2712.

7. Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, Urban N, Gough S, Schurman KM, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer. 2007. 109:221–227.

8. Goff BA, Mandel L, Muntz HG, Melancon CH. Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2000. 89:2068–2075.

9. Jacobs I, Davies AP, Bridges J, Stabile I, Fay T, Lower A, et al. Prevalence screening for ovarian cancer in postmenopausal women by CA 125 measurement and ultrasonography. BMJ. 1993. 306:1030–1034.

10. Olivier RI, Lubsen-Brandsma MA, Verhoef S, van Beurden M. CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound monitoring in high-risk women cannot prevent the diagnosis of advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006. 100:20–26.

11. Jacobs IJ, Skates SJ, MacDonald N, Menon U, Rosenthal AN, Davies AP, et al. Screening for ovarian cancer: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999. 353:1207–1210.

12. Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Hallett R, Ryan A, Burnell M, Sharma A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). Lancet Oncol. 2009. 10:327–340.

13. Webb PM, Purdie DM, Grover S, Jordan S, Dick ML, Green AC. Symptoms and diagnosis of borderline, early and advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004. 92:232–239.

14. Friedman GD, Skilling JS, Udaltsova NV, Smith LH. Early symptoms of ovarian cancer: a case-control study without recall bias. Fam Pract. 2005. 22:548–553.

15. An experiment in earlier detection of ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2007. 369:2051.

16. Hamilton W, Peters TJ, Bankhead C, Sharp D. Risk of ovarian cancer in women with symptoms in primary care: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2009. 339:b2998.

17. Lataifeh I, Marsden DE, Robertson G, Gebski V, Hacker NF. Presenting symptoms of epithelial ovarian cancer. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005. 45:211–214.

18. Eltabbakh GH, Yadav PR, Morgan A. Clinical picture of women with early stage ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1999. 75:476–479.

19. Andersen MR, Goff BA, Lowe KA, Scholler N, Bergan L, Dresher CW, et al. Combining a symptoms index with CA 125 to improve detection of ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2008. 113:484–489.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download