Abstract

Objective

To compare the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel plus platinum followed by radical hysterectomy with radical surgery alone in patients with stage IB2-IIA bulky cervical cancer.

Methods

From November 1999 to September 2007, stage IB2-IIA cervical cancers with tumor diameter >4 cm, as measured by MRI, were managed with two cycles of preoperative paclitaxel and platinum. As a control group, we selected 35 patients treated with radical surgery alone.

Results

There were no significant between group differences in age, tumor size, FIGO stage, level of SCC Ag, histopathologic type and grade. Operating time, estimated blood loss, the number of lymph nodes yielded and the rate of complications were similar in the two groups. In surgical specimens, lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI), nodal metastasis and parametrial involvement did not differ significantly between the two groups. In the neoadjuvant group, pathologic tumor size was significantly smaller and fewer patients had deep cervical invasion. Radiotherapy, alone and in the form of concurrent chemoradiation, was administered to more patients treated with radical surgery alone (82.9% vs. 52.9%, p=0.006). No recurrence was observed in patients who could avoid adjuvant radiotherapy owing to improved risk factors after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. There were no significant differences in 5-year disease free and overall survival.

Conclusion

As neoadjuvant chemotherapy would improve pathologic prognostic factors, adjuvant radiotherapy can be avoided, without worsening the prognosis, in patients with locally advanced bulky cervical cancer. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy would be improving the quality of life after radical hysterectomy in patients with bulky cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer is the most prevalent gynecological malignancy in many developing countries.1 Surgery is the most effective therapeutic method in patients with invasive cancer confined to the cervix. The 5-year survival rate after surgery for patients with stage IB1 disease exceeds 90%, but is only 60-70% in patients with tumors >4 cm in size.2-4 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been administered to patients with locally advanced cervical cancer to improve outcome.5,6 Among the main advantages of neoadjuvant chemotherapy are the potential elimination of micrometastases, shrinkage of the primary tumor to achieve radical operability and the surgical down-staging of patients.7,8 Despite its high response rates,6,7,9-12 neoadjuvant chemotherapy for cervical cancer still remains controversial. While an Italian trial and a meta-analysis has demonstrated that neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy followed by radical surgery affords survival benefits in patients with stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer,13,14 a recent phase III GOG trial failed to demonstrate any survival benefit.15 The discrepancies in these results may be due to a variety of clinical and biological factors, and the use of different chemotherapeutic regimens based on cisplatin.15-18 Several new drug regimens may have more activity in cervical cancer. We therefore tested the efficacy of paclitaxel plus platinum neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage IB2 to IIA cervical cancer of size >4 cm, as evaluated by MRI, on pathologic prognostic factor and long-term survival.

All patients with stage IB2 or IIA cervical cancers with tumor size >4 cm on MRI treated with paclitaxel plus platinum between November 1, 1999 and September 30, 2007 were retrospectively reviewed. All patients had primary, previously untreated, histologically confirmed cervical cancer. Patients treated with other chemotherapy regimens were excluded. The patients with para-aortic lymph node metastasis or simultaneous other malignancies after primary surgery were also excluded. During the same period, the control group consisted of patients with tumor size >4 cm who underwent radical surgery alone, which was defined as the primary surgery (PS) group. Clinical staging procedures including pelvic examination, chest X-ray, cystoscopy, rectosigmoidoscopy, and intravenous pyelogram were performed in all patients. The patients underwent MRI to evaluate tumor size during the initial diagnostic procedure and just before surgery after 2 cycles of neadjuvant chemotherapy.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy consisted of 2 cycles of intravenous paclitaxel 135 mg/m2 and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 or carboplatin AUC 5 3-week intervals interval. All patients underwent type III radical hysterectomy with systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy plus, if indicated, para-aortic lymphadenectomy, within 3 weeks of completion of the second chemotherapy cycle. Postoperative concurrent chemoradiation or radiotherapy alone was administered to high risk patients, defined as those with at least one major risk factor, including positive nodes, parametrial involvement and positive surgical margin, or two or more minor risk factors, including tumor size, depth of invasion and lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI).

Tumor response was evaluated for tumor size measured by MRI at the initial diagnostic procedure and just before surgery after neadjuvant chemotherapy according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST).19 Only 42 patients who took pre- and post-chemotherapy MRI were assessed for tumor response. Complete response (CR) was defined as the complete disappearance of the tumor in the cervix, partial response (PR) as a ≥30% decrease of longest diameter (LD), progressive disease (PD) as a ≥20% increase of LD, and stable disease (SD) as a decrease or increase less than PR or PD. Patients who achieved CR or PR were defined as responders, whereas those who achieved PD or SD were defined as non-responders.

SPSS ver. 12.0 was used for statistical analysis. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. Mean, median, and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables, which were compared using the t test. Survival time was calculated from the date of the neoadjuvant chemotherapy was started. The survival rate was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

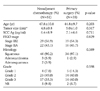

In this study, 51 patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) followed by radical hysterectomy and 35 underwent immediate radical hysterectomy. The two groups were similar in age at diagnosis, tumor size, level of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) Ag, FIGO stage, and histological type and grade (Table 1).

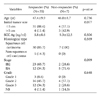

There were no life-threatening complications following chemotherapy. All patients successfully underwent radical hysterectomy and complete nodal dissection. After NAC, CR was observed in 3 of 42 (7.1%) patients, PR in 32 (76.2%) patients, and SD in 7 (16.7%) patients, making the overall response rate after NAC 83.3% (35/42). There were no significant differences in age, level of SCC Ag, and histological type and grade between responders and non-responders (Table 2). The patients with larger than 5 cm sized tumor or FIGO stage IIA showed poorer response, but there were no significant differences (p=0.077, p=0.099, respectively).

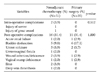

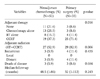

When we compared operative and pathologic data after radical hysterectomy in the two groups, we found no significant differences in operating time, estimated blood loss and the number of lymph nodes (Table 3). More patients in NAC group required blood transfusions and the postoperative change in hemoglobin was significantly lower (p=0.009). Nodal metastasis were observed in 35.3% (18/51) of the patients in NAC group, compared with 48.6% (17/35) in the primary surgery (PS) group; LVSI was observed in 43.1% and 57.2%, respectively, and parametrial involvement in 29.4% and 28.6%, respectively. However, tumor size was much smaller and cervical invasion was more superficial in NAC group. Despite that laparoscopic radical hysterectomy was mainly performed in the NAC group (23.5% vs. 2.9%, p=0.012), there were similar complication rates between the two groups (Table 4). Postoperative adjuvant therapy was administered to 40 patients (78.4%) of the NAC group and to 32 (91.4%) of PS group (p=0.142). Fewer patients treated with NAC received adjuvant radiotherapy, either alone or as concurrent chemoradiation (52.9% vs. 82.9%, p=0.006) (Table 5).

The median follow-up time for NAC group was 48.5 months, during which three recurrences (5.9%) and three tumor-related deaths were recorded. All three patients had only distant metastases. However, there was no recurrence in the patients without adjuvant radiotherapy owing to improved pathologic risk factors after NAC. In PS group, the median follow-up time was 32 months, during which four recurrences (11.4%) and three tumor-related deaths were observed. All four patients also had only distant metastases.

The 5-year disease-free survival rates in NAC and PS groups were 93.3% and 81.5%, respectively (p=0.198), and the 5-year overall survival rates were 92.8% and 91.1%, respectively (p=0.426) (Fig. 1). In addition, there were no differences in survival rate among the three groups (responders vs. non-responder vs. primary surgery patients) (Fig. 2).

Prognostic factors for the recurrence of cervical cancer are pathologic findings of parametrial involvement, lymph node metastasis and positive surgical margins,20,21 in addition to tumor size and depth of invasion.22 Larger tumors frequently have higher rates of lymph node metastasis as well as local, regional, and distant failure, and patients with larger tumors have lower survival rates.20,23 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has shown a high response rate, 53-94%, with complete pathological response rates of 10-13.8%.8,11,24-26 We observed a complete response of 7.1% (3/42), along with significant reductions in tumor size and depth of invasion after NAC compared with the PS group. These results suggest that NAC improved operability in patients with bulky cervical cancer by decreasing tumor size. However, chemotherapy-induced tumor necrosis may result in dense fibrosis and adhesions, which make surgical planes difficult to be maintained.27 This study showed that a higher proportion of patients in the NAC group required blood transfusions. It is inferred that more blood loss may be attributed to tumor necrosis and dense fibrosis after chemotherapy. The postoperative hemoglobin decrease in the NAC group was significantly lower, suggesting that this may have been due to prevention of anticipated blood loss as well as the propensity and variable criteria of the anesthesiologist and/or surgeon. However, more patients successfully underwent laparoscopic radical hysterectomy without conversion into laparotomy. Laparoscopic radical surgery can be undertaken without increase of complication rates in patients with bulky tumors.

While a lower rate of nodal metastasis rate has been reported in patients with locally advanced stage IB-IIB tumors after NAC than in those treated with PS (7-25% vs. 30-34%),7,28,29 the NAC group had no beneficial effect on lymph node metastasis in this study. LVSI and parametrial involvement were also similar in the two groups. Although NAC was less effective in reducing lymph node metastases, LVSI, and parametrial involvement, it was more effective in reducing the size of tumor and the depth of invasion. Therefore, two cycles or doses of chemotherapy might be insufficient for reducing the number of lymph nodes metastases or LVSI. On the other hand, these findings suggest that NAC might be ineffective in the management of high-risk patients with lymph node metastasis. It is important to select appropriate patients who would benefit most from NAC prior to surgery. Patients with age of younger than 35 years and adeno- or adenosquamous carcinoma have been reported to be associated with resistance to NAC,30 however, we found that age and histological type were not associated with poor prognosis, and tumors with larger than 5 cm or FIGO stage IIA had represented rather lower response. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be considered in treating younger patients with bulky tumor without anticipating poor response.

Of the patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 63-81% were treated postoperative concurrent chemoradiation.18,31 In this study, a significantly lower proportion of patients treated with NAC received postoperative radiation (52.9% vs. 82.9%) than those undergoing PS. Despite this difference, the disease-free and overall survival rates in the two groups were not statistically different, although the NAC group had a tendency of higher 5-year disease-free survival rate than the PS group. Also, no recurrence was observed in patients who avoided adjuvant radiotherapy owing to changed pathologic risk factors after NAC. However, as there were no differences among responders and nonresponders of the NAC group and PS group, we postulate that rather good survival rate of the nonresponder group may be attributed to postoperative concurrent chemoradiation. As the present study additionally showed that responders of the NAC group with lower postoperative radiation rates had similar survival rate to the PS group, our results highlights that no accentuation of survival may occur in the responder group even if adjuvant radiotherapy is not added owing to changed pathologic prognostic factors after NAC.

These findings suggest that NAC might be a good treatment option in sexually active, premenopausal women with locally advanced bulky cervical cancer affording better quality of life, by allowing them to avoid postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy. This approach may provide conservation of ovarian and sexual function in these patients without worsening the prognosis.

The limitations of our study were its retrospective design, the small number of patients, and limited long-term follow-up. However, our findings indicate that NAC has an effect on pathologic prognostic factors, allowing patients with locally advanced bulky cervical cancer to avoid adjuvant radiotherapy without worsening their prognosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Disease-free survival and (B) overall survival rates in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy and primary surgery groups.

NAC: neoadjuvant chemotherapy, PS: primary surgery.

Fig. 2

(A) Disease-free survival and (B) overall survival rates in responder, nonresponder and primary surgery groups.

PS: primary surgery.

References

1. Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of 25 major cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999. 80:827–841.

2. Alvarez RD, Soong SJ, Kinney WK, Reid GC, Schray MF, Podratz KC, et al. Identification of prognostic factors and risk groups in patients found to have nodal metastasis at the time of radical hysterectomy for early-stage squamous carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1989. 35:130–135.

3. Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Nene SM, Camel HM, Galakatos A, Kao MS, et al. Effect of tumor size on the prognosis of carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with irradiation alone. Cancer. 1992. 69:2796–2806.

4. Thoms WW Jr, Eifel PJ, Smith TL, Morris M, Delclos L, Wharton JT, et al. Bulky endocervical carcinoma: a 23-year experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992. 23:491–499.

5. Kim DS, Moon H, Kim KT, Hwang YY, Cho SH, Kim SR. Two-year survival: preoperative adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of cervical cancer stages Ib and II with bulky tumor. Gynecol Oncol. 1989. 33:225–230.

6. Friedlander ML, Atkinson K, Coppleson JV, Elliot P, Green D, Houghton R, et al. The integration of chemotherapy into the management of locally advanced cervical cancer: a pilot study. Gynecol Oncol. 1984. 19:1–7.

7. Sardi J, Sananes C, Giaroli A, Bayo J, Rueda NG, Vighi S, et al. Results of a prospective randomized trial with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in stage IB, bulky, squamous carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1993. 49:156–165.

8. Hwang YY, Moon H, Cho SH, Kim KT, Moon YJ, Kim SR, et al. Ten-year survival of patients with locally advanced, stage ib-iib cervical cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2001. 82:88–93.

9. Scarabelli C, Zarrelli A, Gallo A, Visentin MC. Multimodal treatment with neoadjuvant intraarterial chemotherapy and radical surgery in patients with stage IIIB-IVA cervical cancer: a preliminary study. Cancer. 1995. 76:1019–1026.

10. Park SY, Kim BG, Kim JH, Lee JH, Lee ED, Lee KH, et al. Phase I/II study of neoadjuvant intraarterial chemotherapy with mitomycin-C, vincristine, and cisplatin in patients with stage IIb bulky cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 1995. 76:814–823.

11. Giaroli A, Sananes C, Sardi JE, Maya AG, Bastardas ML, Snaidas L, et al. Lymph node metastases in carcinoma of the cervix uteri: Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and its impact on survival. Gynecol Oncol. 1990. 39:34–39.

12. Yamakawa Y, Fujimura M, Hidaka T, Hori S, Saito S. Neoadjuvant intraarterial infusion chemotherapy in patients with stage IB2-IIIB cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000. 77:264–270.

13. Benedetti-Panici P, Greggi S, Colombo A, Amoroso M, Smaniotto D, Giannarelli D, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical surgery versus exclusive radiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell cervical cancer: results from the Italian multicenter randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2002. 20:179–188.

14. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer Meta-analysis Collaboration. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 21 randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 2003. 39:2470–2486.

15. Eddy GL, Bundy BN, Creasman WT, Spirtos NM, Mannel RS, Hannigan E, et al. Treatment of ("bulky") stage IB cervical cancer with or without neoadjuvant vincristine and cisplatin prior to radical hysterectomy and pelvic/para-aortic lymphadenectomy: A phase III trial of the gynecologic oncology group. Gynecol Oncol. 2007. 106:362–369.

16. Kim DS, Moon H, Hwang YY, Cho SH. Preoperative adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of cervical cancer stage Ib, IIa, and IIb with bulky tumor. Gynecol Oncol. 1988. 29:321–332.

17. Weiner SA, Aristizabal S, Alberts DS, Surwit EA, Deatherage-Deuser K. A phase II trial of mitomycin, vincristine, bleomycin, and cisplatin (MOBP) as neoadjuvant therapy in high-risk cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1988. 30:1–6.

18. Behtash N, Nazari Z, Ayatollahi H, Modarres M, Ghaemmaghami F, Mousavi A. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical surgery compared to radical surgery alone in bulky stage IB-IIA cervical cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006. 32:1226–1230.

19. Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000. 92:205–216.

20. Piver MS, Chung WS. Prognostic significance of cervical lesion size and pelvic node metastases in cervical carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1975. 46:507–510.

21. Fuller AF, Elliott N, Kosloff C, Lewis JL. Lymph node metastases from carcinoma of the cervix, stages IB and IIA: implications for prognosis and treatment. Gynecologic Oncology. 1982. 13:165–174.

22. Mohar A, Frias-Mendivil M. Epidemiology of cervical cancer. Cancer Invest. 2000. 18:584–590.

23. Delgado G, Bundy BN, Fowler WC Jr, Stehman FB, Sevin B, Creasman WT, et al. A prospective surgical pathological study of stage I squamous carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 1989. 35:314–320.

24. Modarress M, Maghami FQ, Golnavaz M, Behtash N, Mousavi A, Khalili GR. Comparative study of chemoradiation and neoadjuvant chemotherapy effects before radical hysterectomy in stage IB-IIB bulky cervical cancer and with tumor diameter greater than 4 cm. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005. 15:483–488.

25. Kigawa J, Minagawa Y, Ishihara H, Itamochi H, Kanamori Y, Terakawa N. The role of neoadjuvant intraarterial infusion chemotherapy with cisplatin and bleomycin for locally advanced cervical cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1996. 19:255–259.

26. Namkoong SE, Park JS, Kim JW, Bae SN, Han GT, Lee JM, et al. Comparative study of the patients with locally advanced stages I and II cervical cancer treated by radical surgery with and without preoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 1995. 59:136–142.

27. Paladini D, Raspagliesi F, Fontanelli R, Ntousias V. Radical surgery after induction chemotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: a feasibility study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1995. 5:296–300.

28. Panici PB, Scambia G, Baiocchi G, Greggi S, Ragusa G, Gallo A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical surgery in locally advanced cervical cancer: prognostic factors for response and survival. Cancer. 1991. 67:372–379.

29. Eddy GL, Manetta A, Alvarez RD, Williams L, Creasman WT. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with vincristine and cisplatin followed by radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy for FIGO stage IB bulky cervical cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group pilot study. Gynecol Oncol. 1995. 57:412–416.

30. Huang HJ, Chang TC, Hong JH, Tseng CJ, Chou HH, Huang KG, et al. Prognostic value of age and histologic type in neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical surgery for bulky (>/=4 cm) stage IB and IIA cervical carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003. 13:204–211.

31. Duenas-Gonzalez A, Lopez-Graniel C, Gonzalez-Enciso A, Cetina L, Rivera L, Mariscal I, et al. A phase II study of multi-modality treatment for locally advanced cervical cancer: neoadjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel followed by radical hysterectomy and adjuvant cisplatin chemoradiation. Ann Oncol. 2003. 14:1278–1284.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download