Abstract

Objective

We have assessed the accuracy of frozen section diagnosis and the outcomes of misdiagnosis in borderline tumors of the ovary (BTO) according to frozen section.

Methods

All pathology reports with BTO in both frozen and permanent section analyses between 1994 and 2008 at Seoul St. Mary's Hospital were reviewed. Frozen section diagnosis and permanent section histology reports were compared. Logistic regression models were conducted to evaluate the correlation of patient and tumor characteristics with diagnostic accuracy. The clinical outcomes of misdiagnosis were evaluated.

Results

Agreement between frozen section diagnosis and permanent histology was observed in 63 of 101 patients (62.4%). Among the 76 patients with frozen section proven BTO, under-diagnosis and over-diagnosis occurred in 8 of 76 (10.5%) and 5 of 76 patients (6.6%), respectively. Mean diameter of under-diagnosed tumor was larger than matched BTO (21.0±11.4 vs. 13.7±7.1; p=0.021). Tumor size 20 cm was determined as the optimal cut-off for under-diagnosis (50% sensitivity, 87.3% specificity). Among 8 under-diagnosed patients, no patient relapsed. Among 5 over-diagnosed patients, 2 patients < 35 years of age had fertility-preserving surgery.

Conclusion

Although frozen section diagnosis is an important and reliable tool in the clinical management of patients with ovarian tumors, over-diagnosis and under-diagnosis are relatively frequent in frozen proven BTO. Surgical decision-making for BTO based on frozen section diagnosis should be done carefully, especially in large tumors.

Borderline tumors are a heterogeneous group of lesions defined histologically by atypical epithelial proliferation without stromal invasion.1 Borderline tumors of the ovary (BTO) represent 10-20% of ovarian epithelial tumors.2 BTO have a good prognosis and are typically present in the younger age group.3 Thus, the disease frequently affects women with a desire to preserve childbearing potential.

Surgical removal of a BTO is the treatment of choice; however, controversy exists on the extent of the surgical approach. Recently, fertility-preserving surgery in early stage BTO has gained acceptance.3,4 Because surgical decision-making is established intra-operatively, frozen section diagnosis must be sufficiently accurate to support conservative surgery. However, frozen section diagnosis of BTO is less reliable than frozen section diagnosis of benign or malignant ovarian tumors.5-14 Thus, some investigators have sought to find significant factors related to misdiagnosis. Houck et al.8 found that mucinous histology was the only significant predictor for under-diagnosis by frozen section. Tempfer et al.9 reported that a tumor size >3 cm was the only independent factor related to under-diagnosis by frozen section. Also, Brun et al.10 reported that in addition to tumor characteristics, the experience of the pathologist influences the accuracy of frozen section diagnosis. But, the number of patients was small and the number of clinico-pathologic factors to evaluate was limited. Also, they did not show the clinical impact of misdiagnosis. Furthermore, their study population was not practical, because in the clinical setting, BTO according to frozen or permanent section is indefinable.

Thus, we evaluated the factors influencing the accuracy of frozen section analysis and the clinical outcomes of misdiagnosis in patients with BTO according to frozen section.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for medical record and pathology report reviews. Patients who underwent exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy for adnexal tumors and who were diagnosed as BTO by intra-operative frozen section analysis were included in this study. The medical records from 101 patients who were diagnosed with a BTO according to frozen or permanent section were available for review. The surgical procedures were performed between 1994 and 2008 at Kangnam St. Mary's Hospital in Seoul, Korea. During that period, all frozen section specimens were analyzed by a total of 11 board certified pathologists. All slides were reviewed again by one pathologist who is expert in gynecology for this study. The frozen section diagnosis was compared with the permanent section diagnosis with respect to benign, borderline, and malignant features.

Fresh pathologic specimens were sent to the Pathology department. After measurement of tumor size, the most suspicious areas of the mass, with emphasis on solid, papillary, or necrotic regions, were chosen for frozen section. Each specimen had one to seven of the most representative sections sampled for frozen section. In all cases, a minimum of 1 section per 1 cm of maximal tumor diameter was examined for permanent section diagnosis.

The medical records were reviewed for parameters potentially influencing the accuracy of frozen section diagnosis, such as the number of sections, the experience of the pathologist, and the characteristics of the patient and the tumor. Logistic regression models were performed to determine the possible factors related to the misdiagnosis (over- or under-diagnosis). p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The clinical outcomes of misdiagnosed patients were also reviewed retrospectively. In the case of under-diagnosis, relapse and reoperation were considered; in case of over-diagnosis, preservation of fertility was the primary consideration.

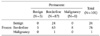

During the period study, 101 patients were diagnosed as BTO by frozen or permanent section pathology. The agreement, sensitivity, and positive predictive values of the frozen section diagnosis of BTO were 62.4%, 71.6%, and 82.9%, respectively (Table 1). To evaluate the accuracy of intra-operative frozen section diagnosis, we confined the study population to 76 patients who were diagnosed as BTO by frozen section analysis only. The mean age of the patients at the time of admission was 41.4±17.7 years. Based on histological assessment, 51 tumors were mucinous, 18 tumors were serous, and 7 tumors were mixed. Four patients had bilateral disease and 5 patients had tumor extension beyond the ovary. The mean diameter of mucinous and serous tumors was 16.41±8.31 and 9.21±3.29 cm, respectively. Tumor markers (CA 125 or CA 19-9) were elevated in 25 patients. Fifty-nine patients underwent imaging studies (CT or MRI) before exploratory surgery. In this series, the diagnosis of BTO was established for 25 tumors (25/59).

Among the 76 patients with frozen section proven BTO, sixty three patients (82.9%) were correctly diagnosed by frozen section analysis. Under-diagnosis and over-diagnosis occurred in 8 of 76 (10.5%) and 5 of 76 patients (6.6%), respectively (Table 1). The mean diameter of under-diagnosed tumor was larger than the matched BTO (21.0±11.4 vs. 13.7±7.1; p=0.021) (Table 2). Although not statistically significant, over-diagnosis appeared in unilateral tumors and tended to be in the group with section numbers ≤2. The specialized pathologist did not perform under-diagnosis.

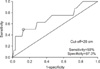

Based on the above results, we performed the ROC curve analysis to find out the cut-off value of tumor size for overdiagnosis (Fig. 1). Considering the relatively small number of under-diagnosed cases, we used the criteria which satisfied at least 50% of sensitivity and maximum value of specificity. Tumor size 20 cm was determined as the optimal cut-off for under-diagnosis, with 50% sensitivity and 87.3% specificity. Using this cut-off level, patients with tumor size greater than 20 cm were more likely to be under-diagnosed (OR, 6.88; 95% CI, 1.43 to 33.11, p=0.016), and although we were unable to determine the reason, no imaging study was associated with over-diagnosis (OR, 7.94; 95% CI, 1.17 to 52.63, p=0.034) (Table 3).

The clinical outcomes of misdiagnosed patients are shown in Table 4. Malignant lesions were interpreted as borderline lesions by frozen section in eight cases. Among these eight patients, one patient underwent a restaging procedure and all patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. There were no relapses. Among 6 over-diagnosed patients, 2 patients <35 years of age underwent fertility-preserving surgery.

In endometrial, cervical, and vulvar cancers, diagnosis can be established before surgery. Thus, the management can be discussed with the patients pre-operatively, especially for women who want to preserve fertility. Even though pre-operative imaging studies and tumor markers may be of help to the surgeon with respect to ovarian tumors, the exact diagnosis can only be made at the time of exploratory surgery.15

A frozen section diagnosis offers an important and helpful adjunct to the intra-operative diagnosis and has greatly impacted the care of gynecologic oncology patients.16 Frozen section diagnosis agrees with permanent pathology of malignancy in 90-94% of cases.17,18 However, frozen section diagnosis of BTO is less reliable.8,10 In the pooled data analysis, Tempfer et al.9 reported that agreement between frozen section diagnosis and definitive histology was observed in 199/317 (62.8%) patients. Our study also showed a similar level of accuracy; specifically, agreement occurred in 62.4% of the cases. Therefore, all patients should be counseled before surgery about the value of frozen section and the possible treatment options.19

Several series have been conducted to evaluate the factors influencing the accuracy of a frozen section diagnosis in patients with BTO. Houck et al.8 found that mucinous histology was the only significant predictor for under-diagnosis by frozen section. Tempfer et al.9 reported that a tumor size >3 cm was the only independent factor related to under-diagnosis by frozen section. Also, Brun et al.10 reported that in addition to tumor characteristics, the experience of the pathologist influences the accuracy of frozen section diagnosis. However, their study population was not practical, because in the clinical setting, BTO according to frozen or permanent section is indefinable. For example, Tempfer et al.9 reported 27 of 96 cases (31.7%) were under-diagnosed by frozen section. But these 27 cases consisted of 4 cases malignant tumors whose frozen section diagnosis was BTO. Therefore, the above report is about the accuracy of frozen section diagnosis in malignant ovarian tumors but not in BTO.

It is difficult to interpret the implications of the under-diagnosis rate (28%) due to inappropriate inclusion criteria. Actually, when the frozen section diagnosis was reported as BTO, how to interpret the results and how to make a decision is more important in the practical clinical setting. Therefore, in our study, we confined the study population to 76 patients who were diagnosed as BTO by frozen section analysis only.

In our study, although we evaluated multiple factors other than those previously reported, only tumor diameter >20 cm were more likely to be under-diagnosed based on univariate analysis. Because of the lower frequency and diagnostic difficulty of BTO, many authors have concluded that diverse factors influence the accuracy of frozen section diagnosis. Indeed, even the tumor size cut-off level has differed from report-to-report (i.e., 3, 10, and 20 cm). Nevertheless, large tumor size and mucinous histology are thought to be the most powerful predictors of misdiagnosis.

We not only evaluated the accuracy and factors influencing misdiagnosis in previously reported studies, but we also reviewed the clinical outcomes arising from misdiagnosis. Although patients with BTO have an excellent prognosis, the risk of recurrence remains.20 Therefore, in cases of underdiagnosis, surgeons have concerns about reoperation or recurrence. All eight patients with malignant tumors that were interpreted as borderline by frozen section received adjuvant chemotherapy and there were no recurrences during follow-up (78.5±57.4 months). Concerning the restaging procedure, retrospective studies have shown that, even when such staging procedures are performed, they have no impact on survival in patients with BTO.21-23 However, if there are no descriptions regarding the abdominal cavity and peritoneal surfaces, restaging is recommended because in 39% of BTO, the omentum is involved and 9% have invasive implants.24

On the other hand, in cases of over-diagnosis, surgeons have concerns about fertility-preserving surgery. In the 5 over-diagnosed patients reviewed in the current study, all 2 patients <35 years of age underwent fertility-preserving surgery. Even in select cases of invasive ovarian cancer, fertility-preserving surgery can be considered in patients with apparent early stage disease who wish to preserve fertility.25-27 It is clearly a valuable option to postpone definitive surgical treatment of a BTO until the permanent pathology report is available.9

In conclusion, although frozen section diagnosis is an important and reliable tool in the clinical management of patients with ovarian tumors, over-diagnosis and under-diagnosis are relatively frequent in frozen proven BTO. Surgical decision-making for BTO based on frozen section diagnosis should be done carefully, especially in large tumors.

References

1. Russell P. Surface epithelial-stromal tumors of the ovary. 1994. New York: Springer Verlag.

2. Pecorelli S, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P. FIGO annual report of the results of treatment in gynaecological cancer: carcinoma of the ovary. J Epidemiol Biostat. 1998. 3:75.

3. Tinelli R, Tinelli A, Tinelli FG, Cicinelli E, Malvasi A. Conservative surgery for borderline ovarian tumors: a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2006. 100:185–191.

4. Cadron I, Leunen K, Van Gorp T, Amant F, Neven P, Vergote I. Management of borderline ovarian neoplasms. J Clin Oncol. 2007. 25:2928–2937.

5. Ilvan S, Ramazanoglu R, Ulker Akyildiz E, Calay Z, Bese T, Oruc N. The accuracy of frozen section (intraoperative consultation) in the diagnosis of ovarian masses. Gynecol Oncol. 2005. 97:395–399.

6. Geomini P, Bremer G, Kruitwagen R, Mol BW. Diagnostic accuracy of frozen section diagnosis of the adnexal mass: a metaanalysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2005. 96:1–9.

7. Rose PG, Rubin RB, Nelson BE, Hunter RE, Reale FR. Accuracy of frozen-section (intraoperative consultation) diagnosis of ovarian tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994. 171:823–826.

8. Houck K, Nikrui N, Duska L, Chang Y, Fuller AF, Bell D, et al. Borderline tumors of the ovary: correlation of frozen and permanent histopathologic diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2000. 95:839–843.

9. Tempfer CB, Polterauer S, Bentz EK, Reinthaller A, Hefler LA. Accuracy of intraoperative frozen section analysis in borderline tumors of the ovary: a retrospective analysis of 96 cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2007. 107:248–252.

10. Brun JL, Cortez A, Rouzier R, Callard P, Bazot M, Uzan S, et al. Factors influencing the use and accuracy of frozen section diagnosis of epithelial ovarian tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008. 199:244–247.

11. Kayikcioglu F, Pata O, Cengiz S, Tulunay G, Boran N, Yalvac S, et al. Accuracy of frozen section diagnosis in borderline ovarian malignancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000. 49:187–189.

12. Medeiros LR, Rosa DD, Edelweiss MI, Stein AT, Bozzetti MC, Zelmanowicz A, et al. Accuracy of frozen-section analysis in the diagnosis of ovarian tumors: a systematic quantitative review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005. 15:192–202.

13. Menzin AW, Rubin SC, Noumoff JS, Livolsi VA. The accuracy of a frozen section diagnosis of borderline ovarian malignancy. Gynecol Oncol. 1995. 59:183–185.

14. No JH, Jo H, Koh HJ, Han JH, Kim JW, Park NH, et al. Accuracy of frozen section diagnosis for ovarian tumors according to histologic type and malignant potential. Korean J Gynecol Oncol. 2007. 18:48–53.

15. Wakahara F, Kikkawa F, Nawa A, Tamakoshi K, Ino K, Maeda O, et al. Diagnostic efficacy of tumor markers, sonography, and intraoperative frozen section for ovarian tumors. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2001. 52:147–152.

16. Baker P, Oliva E. A practical approach to intraoperative consultation in gynecological pathology. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008. 27:353–365.

17. Pinto PB, Andrade LA, Derchain SF. Accuracy of intraoperative frozen section diagnosis of ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2001. 81:230–232.

18. Boriboonhirunsarn D, Sermboon A. Accuracy of frozen section in the diagnosis of malignant ovarian tumor. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004. 30:394–399.

19. Taskiran C, Erdem O, Onan A, Bozkurt N, Yaman-Tunc S, Ataoglu O, et al. The role of frozen section evaluation in the diagnosis of adnexal mass. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008. 18:235–240.

20. Ren J, Peng Z, Yang K. A clinicopathologic multivariate analysis affecting recurrence of borderline ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2008. 110:162–167.

21. Camatte S, Morice P, Thoury A, Fourchotte V, Pautier P, Lhomme C, et al. Impact of surgical staging in patients with macroscopic "stage I" ovarian borderline tumours: analysis of a continuous series of 101 cases. Eur J Cancer. 2004. 40:1842–1849.

22. Fauvet R, Boccara J, Dufournet C, David-Montefiore E, Poncelet C, Darai E. Restaging surgery for women with borderline ovarian tumors: results of a French multicenter study. Cancer. 2004. 100:1145–1151.

23. Kim K, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Kang SB. Clinical impact of under-diagnosis by frozen section examination is minimal in borderline ovarian tumors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009. 35:969–973.

24. Lin PS, Gershenson DM, Bevers MW, Lucas KR, Burke TW, Silva EG. The current status of surgical staging of ovarian serous borderline tumors. Cancer. 1999. 85:905–911.

25. Querleu D, Gladieff L, Delannes M, Mery E, Ferron G, Rafii A. Preservation of fertility in gynaecologic cancers. Bull Cancer. 2008. 95:487–494.

26. Fader AN, Rose PG. Role of surgery in ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007. 25:2873–2883.

27. Schilder JM, Thompson AM, DePriest PD, Ueland FR, Cibull ML, Kryscio RJ, et al. Outcome of reproductive age women with stage IA or IC invasive epithelial ovarian cancer treated with fertility-sparing therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2002. 87:1–7.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download