Abstract

The development of endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESSs) in foci of endometriosis is extremely rare, and few cases have been reported in the literature to date, particularly with regard to multiple extrauterine ESS. Here we report a case of endometrial stromal sarcoma with multiple metastasis that arose from an ovarian endometriotic lesion. The literature is also briefly reviewed.

Uterine sarcomas are rare tumors that are characterized by rapid progression and a poor prognosis. Histologically, they are classified as leiomyosarcomas, endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESSs) and mixed mesodermal tumors. ESSs are rare neoplasms that comprise approximately 0.2% of all uterine malignancies and about 10-15% of all uterine sarcomas.1 In particular, the development of ESS in endometriotic lesions is very rarely reported. Such extrauterine ESSs can develop in the ovary, fallopian tube, pelvic cavity, colon and retroperitoneum.2 Since ovarian ESS is so rare, very little is known about its pathogenesis.

However, at least in some cases, it may be a metastatic tumor that originates from a uterine tumor, perhaps years after a hysterectomy was performed to remove the primary tumor.

Here we describe a case of low-grade ESS with multiple metastasis that arose from an ovarian endometriotic lesion after hysterectomy.

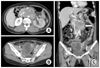

A 50-year-old gravida 4, para 3, abortion 1 woman presented with lower back pain that had lasted for 1 month. In April 2000, the patient underwent total abdominal hysterectomy due to uterine myoma in our hospital. The uterus was sent for pathohistological analysis. Histologically, the myoma appeared to be an adenomyomtous polyp. In September 2008, the patient returned to our hospital due to back pains. Computed tomography (CT) showed a necrotic solid mass measuring 7 cm in diameter in the left adnexa, a para-aortic solid mass lesion, and left renal vein and inferior vena cava thrombosis, which was suggestive of nodal metastasis, probably pelvic nodal metastasis (Fig. 1). We performed a ultrasound-guided biopsy of the para-aortic solid mass. Histological analysis revealed a spindle cell tumor with malignant features, including high cellularity and abnormal mitotic figures. The data from the tumor marker studies are as follows: cancer antigen (CA)-125, 118.4 IU/ml; CA 19-9, 38.7 IU/ml; carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), 1.8 ng/ml; alpha-foetoprotein (AFP), 1.6 ng/ml. The complete blood cell count data are as follows: hemoglobin, 12.6 g/dl; white blood cell count, 8,900/mm3; platelet count, 273,000/mm3. Other examinations, including urinalysis, liver function tests and renal function tests, revealed no abnormalities. Esophagoduodenoscopy revealed reflux esophagitis and gastropathy. Colonoscopy detected hemorrhoids and a 0.2 cm diameter polyp 50 cm from the anal verge. Histologically, the tumor appeared to be a tubular adenoma. On the basis of these findings, we performed an exploratory laparotomy followed by a tumor debulking procedure. The surgical procedure consisted of a bilateral salpingoophorectomy, an appendectomy, an omentum biopsy, a posterior cul-de-sac area biopsy and cytology. In the left adnexa, a 6×5 cm-sized mass was detected. It was composed of a solid and a cystic portion. It adhered to the posterior cul-desac and was accidentally ruptured during the operation. In the right adnexa, multiple small nodules approximately 1cm in diameter were detected. In addition, the right adnexa had adhered to the omentum. A hard nodule about 2-3 cm in diameter was detected at the right infundibulopelvic ligament. The para-aortic lymph node was enlarged to a size of 10×8×5 cm and had invaded the aorta, inferior vena cava and common iliac vessels. Consequently, it was not possible to perform an en bloc excision of the para-aortic mass. The rectum contained numerous nodules up to 0.5 cm in diameter. The appendix, liver surface and diaphragm were normal.

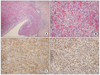

Grossly, the left ovary measured 8.0×6.5×4.0 cm in size and weighed 83 gm. The external surface was pale pink to whitish and smooth. Upon sectioning, the cut surface showed a diffuse dark reddish hemorrhagic lesion containing a focal yellowish solid lesion (Fig. 2). The right ovary had a smooth surface and a unilocular cyst with hemorrhaging. The cul-de-sac mass measured 1.3×0.5 cm in size. The omentum exhibited multiple small nodules.

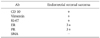

Microscopically, the left ovary exhibited perivascular whorling proliferation of plump spindle cells with scanty cytoplasm and indistinct cell borders. There were many irregular small vessels around the tumor cells and hemorrhage was conspicuous (Fig. 3B). Benign endometrial glands and sparse stroma were observed at the periphery of the tumor (Fig. 3A). Mitotic figures 4-5 per 10 high power field (HPF) were observed. The right ovary exhibited pure ESS nodules with lymphovascular invasion. However, there were no endometriotic foci in the right ovary. The cul-de-sac mass exhibited ESS with endometrial glands. The omentum exhibited metastatic ESS. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the neoplastic cells were immunoreactive to antibodies specific for cluster of differentiation 10 (CD10) (Fig. 3C), Vimentin, Ki-67, estrogen receptor (ER) (Fig. 3D), progesterone receptor (PR) (Table 1).

To treat this ESS, which had arisen from the ovarian endometriotic lesion and exhibited multiple metastasis, chemoradiation therapy was planned. The patient is currently undergoing a course of chemoradiation therapy and hormonal therapy with progestins. Thus, the para-aortic area was irradiated with 5,040 cGY, and 60 mg/m2 cisplatin plus 4,000 mg/m2 ifosfamide is now being administered a total of 6 cycles, at three week intervals. In December 2008, the radiation therapy was completed and the patient had received her fifth chemotherapy. A follow-up CT showed interval improvement of the nodal metastasis in the pelvic and para-aortic spaces. Moreover, the venous thrombosis of the inferior vena cava and the left renal vein was no longer apparent.

The development of ESS in foci of endometriosis is extremely rare and differentiating such tumors from other tumors, such as myogenic, vascular, hemopoietic or epithelial origin tumors, may be difficult.3 The etiology of ESS is unknown. However, there are some reports that suggest that ESS is an endometriosis-associated de novo tumor derived from submesothelial pluripotential mullerian cells.4 Ovarian sex cord stromal tumors with a predominant spindle cell component, Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors and primary mesenchymal tumors such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are also important differential diagnostic considerations.3,5,6 Malignant transformation is an infrequent complication of endometriosis.

Of the extrauterine ESSs, the ovary is the primary site in 76% of cases, while extragonadal sites accounts for the remaining 24%.5 The microscopic differential diagnosis of ovarian ESS includes three major categories of neoplasms: namely, other pure sarcomas; malignant mesodermal mixed tumors, particularly mesodermal adenosarcoma; and sex cord-stromal tumors. The major diagnostic features that are helpful in identifying the endometrioid stromal nature of an ovarian tumor are listed in Table 2. The possible origins of ESS of the ovary are endometriosis of the usual type and pure stromal endometriosis (foci of gland-free endometrial stroma in the ovary).7,8 Similar neoplasms have arisen in association with endometriosis in various other locations.9 It is also possible that some ESSs of the ovary arise directly from ovarian stromal cells that have undergone neometaplasia into endometrial stromal-type cells. In this case, the left ovary showed gradual progression of usual endometriotic foci to low grade ESS (Fig. 3A) with multiple metastatic nodules in the right ovary, cul-de-sac and omentum.

ESS has traditionally been divided into two categories, namely, low-grade and high-grade stromal sarcoma. In most studies, ESS comprises less than 20% of uterine sarcomas and most are low-grade stromal sarcomas (LGSSs).10 The mitotic activity of LGSSs is low, namely, less than 10/10 HPF. High-grade stromal sarcomas (HGSSs), on the other hand, are tumors with mitotic activities that generally exceed 10/10 HPF, although some HGSSs can also have mitotic activities below 10/10 HPF.10

Histological analyses of extrauterine extraovarian ESS reveal infiltrative or tongue-like multinodular growth patterns. Cytological atypia is minimal to mild, and mitotic figures are infrequently seen, namely, up to 5 mitotic figures per 10 HPF. Vascular and lymphatic invasion by the tumor is occasionally present.11

Characteristic immunohistochemical features of ESS include reactivity to antibodies specific for Vimentin, ER and CD10, and nonreactivity to antibodies against CD117, smooth muscle actin (SMA) and cytokeratin (CK). A recent study has shown that among the cases of ESS that were examined, all cases were immunoreactive to anti-CD10 (5/5 cases) and anti-progesterone receptor (10/10 cases) antibody, most reacted with anti-estrogen receptor antibody (9/11 cases), 5/9 and 3/7 were focally positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin, respectively, and all were negative for CD34 (0/7 cases).11 While it is now widely accepted that diffuse CD10 immunoreactivity is a very useful positive predictive marker of ESS, evaluating CD10 immunoreactivity alone is often not helpful for differentiating ESS from its mimics. With regard to the progesterone receptor, while ESSs show high sensitivity to antibodies against this antigen, this immunostain is less specific for differentiating ESS from other mesenchymal tumors. Therefore, a panel of immunohistochemical stains that comprise CD10, estrogen receptor and CD34 may be more helpful for diagnosing extrauterine extraovarian ESS.

To the best of our knowledge, there is one previous report that describes ovarian ESSs, namely, that of Young et al.6, who reviewed 23 cases of ESSs of the ovary. The patients' ages ranged from 20 to 76 years (average, 54 years). The most common presenting symptom was abdominal swelling or pain. In 12 cases, the tumors were unilateral, while in 11 cases they involved both ovaries. Four of the tumors were Stage I, nine were Stage II, eight were Stage III and two were Stage IV because of the presence of pulmonary metastases. In nine of the cases, there was a prior, synchronous or subsequent ESS of the uterus. Nineteen tumors with HPF less than 10 MF/10 HPF were classified as low grade and the remaining four tumors with 12 to 30 MF/10 HPF were designated as high grade. Only two of the 19 patients with low-grade tumors are known to have died of their disease, and nine of those whose tumor had spread beyond the ovary at the time of presentation were alive one or more years postoperatively. However, three of the four patients with high-grade tumors died of their disease within 4 years.

Surgery has always been described as the most effective treatment for uterine sarcomas. Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is considered to be the standard treatment for early stage low-grade ESS.12 Whenever possible, complete tumor clearance should be attempted. The options of adjuvant therapy following surgery include radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy and observation.12-14 The indications and the roles of adjuvant therapies remain controversial. Low grade ESSs are mostly steroid receptor-positive tumors, which means hormonal therapy with progestins, aromatase inhibitors (third generation) and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues is effective. Progesterone is considered to be a useful form of therapy for residual or recurring low grade ESS. LGSSs usually grow slowly and tend to recur many years after the initial surgery. The pelvic cavity followed by the vagina and lung are the main sites of metastases.

In conclusion, the behavior of ESSs of the ovary is similar to that of their uterine counterparts, with the degree of mitotic activity being of major prognostic significance. The prognosis of patients with low-grade tumors is considerably better than that of patients with other pure ovarian sarcomas.15 This case illustrates the findings of low-grade ESS with multiple metastasis arising from an ovarian endometriotic lesion.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Computed tomography showing a necrotic solid mass measuring 7 cm in diameter on the left adnexa (B), a huge para-aortic solid mass lesion, and left renal vein and inferior vena cava thrombosis, which is suggestive of nodal metastasis (A, C). (A, B) axial image, (C) coronal image.

Fig. 2

Gross findings of the left ovary. The cut surface shows a diffuse dark reddish hemorrhagic lesion containing a solid focal yellowish lesion.

Fig. 3

Microscopic findings of the left ovary. The sections of the left ovary exhibit perivascular whorling proliferation of plump and spindle cells with a scanty cytoplasm and indistinct cell borders (A, hematoxylin-eosin, ×200; B, hematoxylin-eosin, ×400). Immunohistochemical staining analyses revealed that the neoplastic cells were immunoreactive to CD10 (C, ×400) and ER (D, ×400).

References

1. Diesing D, Cordes T, Finas D, Loning M, Mayer K, Diedrich K, et al. Endometrial stromal sarcomas: a retrospective analysis of 11 patients. Anticancer Res. 2006. 26(1B):655–661.

2. Yokosuka K, Kumagai M, Aiba S. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma recurring after 9 years. South Med J. 2002. 95:1196–1200.

3. Chang KL, Crabtree GS, Lim-Tan SK, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Primary extrauterine endometrial stromal neoplasms: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993. 12:282–296.

4. Baiocchi G, Kavanagh JJ, Wharton JT. Endometrioid stromal sarcomas arising from ovarian and extraovarian endometriosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1990. 36:147–151.

5. Mourra N, Tiret E, Parc Y, de Saint-Maur P, Parc R, Flejou JF. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the rectosigmoid colon arising in extragonadal endometriosis and revealed by portal vein thrombosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001. 125:1088–1090.

6. Young RH, Prat J, Scully RE. Endometrioid stromal sarcomas of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 23 cases. Cancer. 1984. 53:1143–1155.

7. Hughesdon PE. The origin and development of benign stromatosis of the ovary. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1972. 79:348–359.

8. Hughesdon PE. The endometrial identity of benign stromatosis of the ovary and its relation to other forms of endometriosis. J Pathol. 1976. 119:201–209.

9. Mostoufizadeh M, Scully RE. Malignant tumors arising in endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980. 23:951–963.

10. Zaloudek C, Hedrickson MR. Kurman RJ, editor. Mesenchymal tumors of the uterus. Blaustein's pathology of the female genital tract. 2002. New York: Springer;586–590.

11. Kim L, Choi SJ, Park IS, Han JY, Kim JM, Chu YC, et al. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the small bowel. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2008. 12:128–133.

12. Leunen M, Breugelmans M, De Sutter P, Bourgain C, Amy JJ. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma treated with the aromatase inhibitor letrozole. Gynecol Oncol. 2004. 95:769–771.

13. Paillocher N, Lortholary A, Abadie-Lacourtoisie S, Morand C, Verriele V, Catala L, et al. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: contribution of hormone therapy and etoposide. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2005. 34:41–46.

14. Burke C, Hickey K. Treatment of endometrial stromal sarcoma with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue. Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 104(5 Pt 2):1182–1184.

15. Bodner K, Bodner-Adler B, Obermair A, Windbichler G, Petru E, Mayerhofer S, et al. Prognostic parameters in endometrial stromal sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study in 31 patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2001. 81:160–165.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download