Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to identify the prognostic factors of secondary cytoreductive surgery on survival in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Methods

The medical records of all patients who underwent secondary cytoreductive surgery between May 2001 and October 2007 at the National Cancer Center, Korea were reviewed. Univariate and multivariate analyses were executed to evaluate the potential variables for overall survival.

Results

In total, 54 patients met the inclusion criteria. Optimal cytoreduction to <0.5 cm residual disease was achieved in 87% of patients who had received secondary cytoreductive surgery. Univariate analysis revealed that site of recurrence (median survival, 53 months for the largest tumors in the pelvis vs. 24 months for the largest tumors except for the pelvis; p=0.007), progression free survival (PFS) (median survival, 43 months for PFS≥12 months vs. 24 months for PFS<12 months; p=0.036), and number of recurrence sites (median survival, 49 months for single recurred tumor vs 29 months for multiple recurred tumors; p=0.036) were significantly associated with overall survival. On multivariate analysis, prognostic factors that correlated with improved survival were site of recurrence (p=0.013), and PFS (p=0.043).

Conclusion

In the author's analysis, a significant survival benefit was identified for the recurred largest tumors within the pelvis and PFS≥12 months. Secondary cytoreductive surgery should be offered in selected patients and large prospective studies are needed to define the selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery.

Ovarian cancer represents 25% of all malignancies of the female genital tract but is the most common cause of death among women who develop gynecologic malignancies. The majority of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer have advanced-stage disease at the time of diagnosis. At least 60% of advanced ovarian caner (stage III, IV) patients who meet clinical complete remission after complete primary therapy will ultimately develop a recurrent tumor and will require further treatment.1

The role and theoretical bases of cytoreductive surgery are well established in the treatment of primary epithelial ovarian cancer. The prognostic effect of primary surgical cytoreduction was first reported by Griffiths, who found improved survival in patients with no residual tumor after primary surgery, compared to patients with persistent tumor load.2 Many investigators have since reproduced and confirmed this observation, and a meta-analysis summarizing data from 1989 to 1998 revealed that maximal cytoreduction was one of the most powerful determinants of survival in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer.3 Although randomized investigations evaluating the role of primary cytoreductive surgery are lacking due to the difficulties involved in conducting such trials, the value of debulking a large tumor mass during primary surgery for ovarian cancer has been generally accepted, and primary cytoreductive surgery followed by chemotherapy is considered to be a standard treatment procedure for patients with advanced ovarian cancer.

Patients with recurrent ovarian cancers can be recruited to secondary cytoreduction or salvage chemotherapy. Theoretically, the favorable effects of cytoreductive surgery may also be expected in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Recently, several investigators reported on the advantages of secondary cytoreductive surgery in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer patients. However, the lack of randomized trial data in this field makes it difficult to determine whether such surgery is superior to salvage chemotherapy alone. In addition, prognostic factors affecting the outcomes of such surgery are yet to be firmly identified. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to identify the prognostic factors of secondary cytoreductive surgery and to define the selection criteria associated with improved survival in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Data from 72 patients with recurrent ovarian cancer patients who underwent secondary cytoreductive surgery at the National Cancer Center between May 2001 and October 2007 were retrospectively evaluated. Cytoreductive surgeries were performed in patients who had progression free survival (PFS) ≥6 months, Gynecologic Oncology Group performance status ≤2, and no radiographic findings of extra-abdominal metastasis or unresectable intra-abdominal tumors (peritoneal carcinomatosis, multiple liver metastasis, involvement of porta hepatis, involvement of pancreatic head, involvement of abdominal wall, and involvement of para-aortic lymph node above renal vein). Patients who did not meet these criteria underwent salvage chemotherapy. Exclusion criteria were those patients who received more than 3 chemotherapeutic agents, 3rd or 4th cytoreductive surgery, and pathology other than epithelial ovarian cancer. In total, 54 patients met the above criteria. All patients underwent primary cytoreductive surgery followed by intravenous chemotherapy with platinum-based regimens. Diagnosis of recurrence was established clinically by pelvic examination, imaging studies (ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis and abdomen, and/or positron emission tomography) and serological tests for tumor markers. Data were obtained from the cancer registry and patient medical records.

A thorough evaluation using imaging techniques was performed in order to assess the disease extent prior to surgery. Surgical cytoreduction was not undertaken if the lesion was deemed unresectable following consultation with the radiologist. Patients underwent mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation for 2 days prior to surgery. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Surgery with a therapeutic rather than diagnostic purpose was performed to remove all visible tumor tissue. To achieve this goal, aggressive surgical measures were applied, including extensive intestinal resection, splenectomy, peritonectomy, diaphragmatic stripping or resection, abdominal wall resection and low anterior resection or urinary tract excision, and hepatectomy (with the aid of a hepatic surgeon). We preferred surgical resection rather than use of an argon beam coagulator and cavitron ultrasound surgical aspirator. All procedures were performed by a single gynecological oncologist with an assistant at the fellowship level in gynecologic oncology. The largest dimension of the largest residual tumor after surgery was agreed upon among the attending surgeons as being either none, ≤0.5 cm, 0.5-1.0 cm, 1.0-2.0 cm, or >2 cm. The location of the residual tumor was recorded on a diagram. After recovering from surgery, all patients received individualized salvage chemotherapy based on the initial treatment, response to prior chemotherapy, PFS, and anticipated ability to tolerate the toxicity of salvage chemotherapy. Our chemotherapy principle was paclitaxel-carboplatin as 1st line, topotecan (with or without cisplatin) as 2nd line, docetaxel (with or without cisplatin) as 3rd line, and vinorelbine as 4th line chemotherapy.

PFS was defined as the time from the date of primary cytoreductive surgery to the date of recurrence. Cytoreductive surgery was defined as optimal if the largest dimension of the largest residual tumor measured ≤0.5 cm, and suboptimal if it measured >0.5 cm. Overall survival time was calculated from the date of secondary cytoreductive surgery to death or the date censored.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate survival curves, and differences in survival were tested using the log-rank test. Cox's regression model was used to perform multivariate analysis to evaluate the survival benefit of secondary cytoreductive surgery when adjusted for other favorable prognostic variables. P-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate a significant difference. Data were analyzed using SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age at recurrence was 54 years, with a range of 31 to 72 years. There were five platinum-resistant patients who recurred within 6 months of the end of initial adjuvant chemotherapy. More than half of patients had (59.3%) were stage III disease at the time of primary cytoreduction. Thirty nine patients (72.2%) were serous carcinoma, 2 (3.7%) were mucinous carcinoma, 4 (7.4%) were endometrioid carcinoma, and 3 (5.6%) were clear cell carcinoma. Three patients (5.5%) were grade 1 disease, 15 (27.8%) were grade 2 disease, and 20 (37.0%) were grade 3 disease. Of the 54 patients, only 10 (18.5%) patients received primary cytoreduction at the National Cancer Center and 44 patients (81.5%) underwent primary cytoreduction at other hospitals. Therefore, there was insufficient data regarding residual tumor after primary cytoreduction in the latter group. The median PFS after primary cytoreductive surgery was 24 months, with a range of 6 to 122 months. The median CA-125 before secondary cytoreductive surgery was 102 U/ml, with a range of 6 to 2,350 U/ml (Table 1).

Of the 54 patients, complete resection of all visible tumor tissue was achieved in 32 (59.3%) patients, and residual tumor with a largest dimension of less than 0.5 cm in 15 (27.8%) patients. Thus, optimal resection was achieved in 47 (87.0%) patients.

The outcome and findings of secondary cytoreduction are summarized in Table 2. At secondary cytoreductive surgery, 33 (66.1%) patients underwent para-aortic lymph node dissection, 31 (57.4%) underwent pelvic lymph node dissection, 23 (42.6%) patients underwent splenectomy, 20 (37.0%) underwent diaphragm stripping or resection, 33 (66.1%) patients underwent excision of retained omental tissue, 15 (27.8%) patients underwent low anterior resection (prophylactic colostomy and ileostomy performed in 1 and 2 patients, respectively), 8 (14.8%) patients underwent liver resection, 6 (11.1%) patients underwent small bowel resection and anastomosis, 4 (7.4%) patients underwent large bowel resection and anastomosis, 3 (5.6%) patients underwent total colectomy, 5 (9.3%) patients underwent ureteroureterostomy, 3 (5.6%) patients underwent distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy, 2 (3.7%) patient underwent partial bladder excision, 1 (1.9%) patient underwent abdominal wall resection, and 1 (1.9%) patient underwent a partial ostectomy of the pubic bone.

All patients received the first cycle of chemotherapy before discharge. Postoperative complications occurred in 11 (20.4%) patients, comprising of febrile morbidity in 3 (11.4%) patients, wound dehiscence in 2 (5.7%) patients, ureterovaginal fistula in 1 (1.9%) patient, pancreatic juice leakage in 1 (1.9%) patient, pleural effusion in 1 (1.9%) patient, cellulitis in 1 (1.9%) patient, deep vein thrombosis in 1 (1.9%) patient, and rectal fistula in 1 (1.9%) patient. There were no postoperative deaths (Table 2).

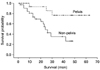

The median follow up was 31 months (range, 1 to 77 months), and the median survival was 42 months (95% CI, 18.3 to 75.3 months). The median overall survival time and progression-free survival time was 42.0 months (95% CI, 32.46 to 47.47 months) and 13.0 months (95% CI, 9.14 to 16.86 months), respectively. Factors influencing overall survival after recurrence were analyzed using univariate analyses (Table 3). Comparison of the median survivals of the patients with only 1 recurrence and the patients with 2 or more recurrences revealed a significant difference (49 vs. 29 months, p=0.036). The median survival of the patients with only pelvic recurrence was longer than that of the patients with non-pelvic recurrence (53 vs. 24 months, p=0.007) (Fig. 1). The PFS also significantly affected the overall survival duration with a median survival of 24 months for a PFS of less than 12 months, and 43 months for a PFS of 12 months or greater (p=0.036) (Fig. 2). The outcome of secondary cytoreduction was not a significant factor for survival (42 months for patients with optimal debulking and 26 months for patients with suboptimal debulking) (p=0.715). Other variables, such as age, CA-125, histology, grade, initial FIGO stage, and largest size of recurrent tumor, did not affect the overall survival significantly on univariate analysis.

On multivariate analysis, we used 4 variables. Those were three variables (PFS, number of recurrence sites, and site of recurrence) found to be significant on the univariate analysis, and 1 more variable (ascites) that showed borderline significance (p=0.093). Site of recurrence (p=0.013) and PFS (p=0.043) were significantly associated with the overall survival after secondary cytoreduction (Table 4).

The majority of patients will ultimately develop recurrent disease and will require further treatment despite high initial response rates to primary treatment in advanced ovarian cancer. Lack of curative options for recurrent disease means the goal of treatment is to maximize overall and disease-free survival and quality of life. Therefore, approaches such as secondary cytoreductive surgery, new second-line chemotherapeutic agents, hormonal therapy and immunotherapy have become the subject of research interest. Among these modalities, secondary cytoreductive surgery and second-line chemotherapy are the mainstays of treatment. Although most recurrent ovarian cancer patients receive second-line chemotherapy, the response rate and the benefits do not reach those of first-line chemotherapy. In addition, the role of secondary cytoreductive surgery remains controversial.

Previous studies have involved a variety of surgical procedures. Although a standard technique for secondary cytoreductive surgery has been suggested by Chen et al.,4 there is at present no general agreement. In particular, Eisenkop et al.5 performed aggressive procedures such as pelvic exenteration to achieve complete surgical resection of carcinomas. We also aimed for complete cytoreduction, and applied aggressive surgical procedures such as multiple bowel resection, partial hepatectomy, splenectomy, and partial ostectomy. We achieved optimal cytoreduction in a considerable proportion of patients with a few major perioperative complications which were easily controlled. The morbidity rates associated with the secondary cytoreductive surgery in this study were considered acceptable, and there were no postoperative deaths. Although there is a limitation that this study was conducted by a single gynecologic oncologist and therefore it cannot be reproducible in other institutions, these outcomes support the hypothesis that the benefits of secondary cytoreductive surgery outweigh the potential deficits. We conclude that aggressive surgical procedures to achieve optimal resection of recurrent tumors should be considered in planning secondary cytoreductive surgery for selected patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

The prognostic role and feasibility of secondary cytoreductive surgery has been examined by several investigators.5-18 However, most such studies are retrospective or non-randomized prospective studies and include only small numbers of patients. In addition, these studies differ in terms of treatment methods, study populations and the definition of optimal cytoreduction, and include limited details regarding preand postoperative chemotherapy.19

Despite the apparent shortcomings associated with previous studies, some consistent findings appear to exist regarding the prognostic impact of secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. The two most important factors affecting survival appear to be the largest dimension of residual tumor after secondary cytoreductive surgery, and the PFS from primary treatment to recurrence. Most previous studies reported better survival in optimal surgery groups.5,7-18,20 Whether the results reflect the skills of the surgical team or merely the inherent biology of the tumor remains unclear. In the present study, overall survival difference between the group of optimal cytoreductive surgery and the group of suboptimal surgery after secondary cytoreductive surgery was not significant statistically. We postulate that there were only 8 patients who underwent suboptimal cytoreduction and this limitation is responsible for these results.

While most previous studies have shown improved survival in groups with a longer PFS, some have reported that the PFS had no impact on prognosis.5,7-9,11-15,17,18,20 In the present study, a longer PFS improved overall survival after secondary cytoreductive surgery. To our knowledge, there has been no studies that have showed that the site of recurrence affected survival in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. The observed relation between the site of recurrent tumor and survival may reflect the difficulty of complete cytoreduction and the inherent aggressive biology of the tumor.

In terms of previous studies, while the largest dimension of residual tumor and PFS were often found to influence survival, other factors were also identified, albeit less consistently. These factors include the use of postoperative chemotherapy, absence of ascites at recurrence, use of preoperative induction chemotherapy, a smaller number of recurrent lesions, fewer prior chemotherapy combinations, younger age, good performance status, and absence of liver metastasis.5-7,11,13,14,16-18,20 In the present study, univariate analysis showed that the number of recurrence sites, site of recurrence, and PFS were significant factors which affected the overall survival duration.

Multivariate analysis identified the site of recurrence and PFS as factors which affected overall survival. Because this study was retrospective, it has limitations in terms of selection bias from the individual selection of patients and interpretation of the data. There were only 10 patients (18.5%) who had undergone primary cytoreductive surgery at the National Caner Center, while the remaining patients were referred from other hospitals after primary cytoreductive surgery. Because the limitation of primary cytoreductive surgery data, we were unable to incorporate the potential impact of this factor on overall survival.

In summary, the current study found that patients with recurrent disease after a PFS of more than 12 months and patients with tumors located within the pelvis may benefit from optimal secondary cytoreductive surgery. Maximizing the benefits of secondary cytoreductive surgery appears to require prudent patient selection and surgical approaches designed to ensure optimal cytoreduction. In the present study, such aggressive surgical techniques were associated with acceptable levels of morbidity and mortality. Ideally, to evaluate both the role and the selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery a large, multi-institutional, and prospective study should be mandated.

References

1. Burke TW, Morris M. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1994. 21:167–178.

2. Griffiths CT. Surgical resection of tumor bulk in the primary treatment of ovarian carcinoma. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1975. 42:101–104.

3. Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002. 20:1248–1259.

4. Chen LM, Karlan BY. Recurrent ovarian carcinoma: is there a place for surgery? Semin Surg Oncol. 2000. 19:62–68.

5. Eisenkop SM, Friedman RL, Spirtos NM. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery in the treatment of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2000. 88:144–153.

6. Ayhan A, Gultekin M, Taskiran C, Aksan G, Celik NY, Dursun P, et al. The role of secondary cytoreduction in the treatment of ovarian cancer: Hacettepe University experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 194:49–56.

7. Berek JS, Hacker NF, Lagasse LD, Nieberg RK, Elashoff RM. Survival of patients following secondary cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1983. 61:189–193.

8. Segna RA, Dottino PR, Mandeli JP, Konsker K, Cohen CJ. Secondary cytoreduction for ovarian cancer following cisplatin therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1993. 11:434–439.

9. Zang RY, Zhang ZY, Li ZT, Chen J, Tang MQ, Liu Q, et al. Effect of cytoreductive surgery on survival of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2000. 75:24–30.

10. Munkarah A, Levenback C, Wolf JK, Bodurka-Bevers D, Tortolero-Luna G, Morris RT, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for localized intra-abdominal recurrences in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2001. 81:237–241.

11. Scarabelli C, Gallo A, Carbone A. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2001. 83:504–512.

12. Tay EH, Grant PT, Gebski V, Hacker NF. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2002. 99:1008–1013.

13. Zang RY, Li ZT, Tang J, Cheng X, Cai SM, Zhang ZY, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: who benefits? Cancer. 2004. 100:1152–1161.

14. Onda T, Yoshikawa H, Yasugi T, Yamada M, Matsumoto K, Taketani Y. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: proposal for patients selection. Br J Cancer. 2005. 92:1026–1032.

15. Gungor M, Ortac F, Arvas M, Kosebay D, Sonmezer M, Kose K. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005. 97:74–79.

16. Gronlund B, Lundvall L, Christensen IJ, Knudsen JB, Hogdall C. Surgical cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian carcinoma in patients with complete response to paclitaxel-platinum. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005. 31:67–73.

17. Chi DS, McCaughty K, Diaz JP, Huh J, Schwabenbauer S, Hummer AJ, et al. Guidelines and selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2006. 106:1933–1939.

18. Tebes SJ, Sayer RA, Palmer JM, Tebes CC, Martino MA, Hoffman MS. Cytoreductive surgery for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007. 106:482–487.

19. Munkarah AR, Coleman RL. Critical evaluation of secondary cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004. 95:273–280.

20. Salani R, Santillan A, Zahurak ML, Giuntoli RL 2nd, Gardner GJ, Armstrong DK, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for localized, recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: analysis of prognostic factors and survival outcome. Cancer. 2007. 109:685–691.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download