Abstract

Purpose

Peritoneal seeding of gastric cancer is known to have a poor prognosis. With the diagnosis of peritoneal seeding, there is no effective treatment modality. Gastrectomy with chemotherapy or primary chemotherapy is basically one of major options for this condition. This study was conducted to compare the clinical outcomes of these treatments and to identify the better way to improve the prognosis of patients with peritoneal seeding.

Materials and Methods

Between 2001 and 2007, gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding by preoperative or intraoperative diagnosis were reviewed retrospectively. The enrolled patients were divided as primary gastrectomy and primary chemotherapy group. Clinicopathologic characteristics and clinical outcomes of groups were analyzed and compared.

Results

Fifty-four patients were enrolled. 21 patients belonged to the group of primary gastrectomy and 33 patients were to the primary chemotherapy group. Among 33 patients of the primary chemotherapy group, 17 patients were received only chemotherapy and 16 patients were received gastrectomy due to the good responses of primary chemotherapy. The 3 years survival rates were 14% in primary gastrectomy group, 55% in patients who received gastrectomy after primary chemotherapy, and 0% in patients with primary chemotherapy only.

Conclusions

Although this study had many limitations, some valuable information was produced. In terms of survival benefits for the gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding, primary gastrectomy and additional gastrectomy after primary chemotherapy revealed the better clinical outcomes. But, prospective randomized clinical study and multi-center study are should be performed to decide proper treatment for gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding.

The prevalence of early stage of gastric cancer patients is increasing annually due to popularization of gastroscopy and these are treated with various methods at early stage of the disease depending on how progressive the disease is. However, when the disease progresses continuously or recurrence, peritoneal seeding is commonly observed during the pathological course and this causes a major concern during the treatment and poor prognosis.

The survival time of gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding is reported to be 3~9 months.(1-3) Although managements such as systematic chemotherapy, peritonectomy, intra-peritoneal chemotherapy and heat therapy are applied to improve the prognosis of advanced gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding, satisfactory methods has not yet found.(4,5) Recently, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy has been applied in various cancers and the results of neoadjuvant chemotherapy have been satisfactory. Therefore, primary chemotherapy is applicable for gastric cancer patients.(6,7) In gastric cancer, the concept of primary chemotherapy is recognized as a contemporary form of treatment for advanced gastric cancer patients who are too difficult to undergo radical gastrectomy and it has been reported in numerous research that a better prognosis is expected if gastrectomy is done to the patients who had a good response to primary chemotherapy.(8,9) The research findings are continuously shown that when primary gastrectomy was performed actively prior to chemotherapy, the response to the chemotherapy increased and resulted in the improved prognosis.(10-12) Therefore, the careful consideration is required to choose a treatment option between primary chemotherapy and primary gastrectomy. Although the status of the disease at the time of diagnosis is an important variable to make a decision, the clinical outcomes of each treatment can be also considered when the decision is made. The researchers in this study intend to provide the clinical outcomes that need to be aware of to choose treatment plans for the gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding after comparing the clinical condition and the prognosis of the patients who had primary chemotherapy to those of the patients who had primary gastrectomy among the gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding.

The subjects were the patients in this hospital who diagnosed metastatic gastric cancer with P1 or P2, but no further metastasis, between January 2001 and December 2007. The patients who had further metastasis to other organs or the patients who were in P3 stage of peritoneal seeding were excluded from this study.

Peritoneal seeding was diagnosed by laparoscopic exploration and it was performed when peritoneal seeding was suspected preoperatively by serosal invasion, thick peritoneum or ascites which can be found on abdominal computerized tomography. The cases which the diagnosis was made after incision of upper abdominal median line but yet peritoneal seeding was not suspected preoperatively were all also included.

In terms of treatment choice, gastrectomy was performed as far as possible, except that it was not impossible to do surgical dissection and excision due to conglomeration caused by infiltration to other organs (T4). Also, gastrectomy was performed for chronic bleeding or obstruction from primary tumor site. All the patients who had gastrectomy also underwent chemotherapy afterwards. The patients who did not have gastrectomy had chemotherapy first; this group of patients was classified as a primary chemotherapy group. The combination chemotherapy method was used with Cisplatin and 5-FU in both the primary chemotherapy group and the gastrectomy group. In cases of deterioration, continued chemotherapy by changing the formula to the ones with Docetaxel, Paclitaxel, and Irinotecan.

The evaluation of chemotherapy response in the primary chemotherapy group was done by performing gastroscopy and abdominal computed tomography (CT) or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT within 3 months after the first dose of chemotherapy. Whether gastric cancer is getting worse or responding to chemotherapy was judged by comparing the improvement of primary tumor range and ulcer with gastroscopy and the changes of existing lymphadenopathy and the onset of new lesions with abdominal CT or PET-CT.

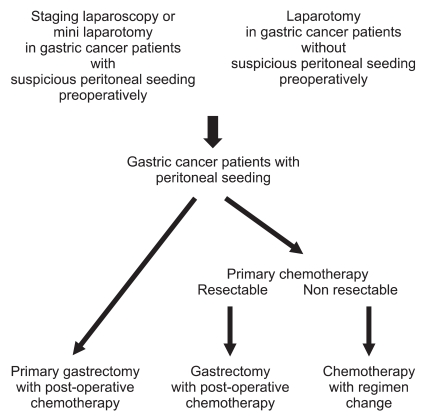

If there is evidence that the primary tumor and the condition of inside peritoneum is improving on the above examination, laparoscopic exploration was performed once again to confirm the status of peritoneal seeding. Providing it is judged to be improved, gastrectomy was performed additionally but, supposing the patients didn't respond to the chemotherapy or it showed the evidence of deterioration, continued with chemotherapy after changing its formula instead of doing gastrectomy (Fig. 1). At least D2 level of lymph node dissection was performed with all the gastrectomy.

Retrospective analysis was carried out based on the records made after surgery regarding clinicopathologic characteristics such as operation methods, tumor size, Borrmann's type, degree of cell differentiation, Lauren's type, invasion depth, and lymph node stage.

SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) used for statistical analysis, Chi-square test for Cross tabulation Analysis, Kaplan-Meier method for survival analysis and the significance was proved wit log-rank test and it is regarded as statistically significant if P-value is less than 0.05 (P<0.05 ).

The total number of patients was 54 people. 21 patients were in the primary gastrectomy group and 33 patients were in the primary chemotherapy group and the male versus female ratio was 2 : 1 and 1.8 : 1 respectively. The age ranged between 32 years old and 75 years old and the average age was 53 years old. The average age of the primary gastrectomy group was 54.9 years old and that of the primary chemotherapy was 56.2 years old showing no significant difference (Table 1).

The stage of peritoneal seeding (P) was evaluated referencing Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma.(13) Table 1 shows the range. There was no significant difference in the proportion of P between two groups.

17 patients from the primary chemotherapy group did not show any signs of improvement and subsequently, they were not received to have gastrectomy and continued with only chemotherapy. The other 16 patients from the same group showed the improvement on the examinations and they had gastrectomy after 2~12 months (5.6 months in average) since the treatment started. Splenectomy was performed with gastrectomy to 3 cases from the primary gastrectomy group and 4 cases from the primary chemotherapy group.

Comparing clinicopathologic characteristics of each group after performing gastrectomy, the average tumor size, Borrmann's type, invasion depth and the stage of lymph node showed no significant difference. The degree of histodifferentiation showed both undifferentiated forms in both groups (Table 2).

The tracing period was 36±12 months and the total 3 year survival rate was 21.3%. The 3 year survival rate of the patients who had additional gastrectomy from the primary chemotherapy group was 55.3% and the average survival time was 36 months and the 3 year survival rate of the primary gastrectomy group was 14.2% and the survival time was 20 months. The survival rate of the patients who continued chemotherapy from the primary chemotherapy group was 0% and the average survival time was 10 months; statistically significant differences were evident between the groups (Fig. 2).

No operation or chemotherapy related mortality or morbidity were found among the patients.

In recent years, although the number of early stage of gastric patients is increasing, advanced cases are still found and if there is peritoneal seeding, the prognosis can be poor.

Because of the poor prognosis, standard conventional chemotherapy would be preferably considered, however, intra-peritoneal and systemic combined chemotherapy, intra-peritoneal heat therapy with cytoreductive surgery, active peritonectomy, induction chemotherapy and post-operation chemotherapy. are recently trying to improve the prognosis.(10,14-16) Furthermore, gastrectomy in the gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding is known to increase the response of chemotherapy, subsequently, improved prognosis. (10-12) Therefore, the authors compared the clinical characteristics and the prognosis according to primary treatments of gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding. Laparoscopy made easy for us to decide the treatment method because it made possible to find out about the level of peritoneal seeding precisely without unnecessary laparotomy when peritoneal seeding is suspected. It is reported that the accuracy of non-invasive diagnosis prior to surgery is about 58~63% and the sensitivity is lower in the case of peritoneal micro metastasis.(17) Comparing to this, the sensitivity of laparoscopic exploration is reported to be above 90%.(18) The diagnosis with peritoneal cytology is different from the one with laparoscopy in many ways, there was no significant difference in actual diagnosis between two.(19)

The total 3 year survival rate was 21.3% in this study but, comparing to this, the total 3 year survival rate was reported to be about 15% in the study of Yonemura et al.(20) and was reported to be about 18% in the study of Glehen et al.(21). In detail, the 3 year survival rate of the patients who had gastrectomy after primary chemotherapy was 55.3% in this study and Yonemura et al.(20) also reported more than 50% but Badgwell et al.(22) reported only 12% in their study. The 3 year survival rate in the primary gastrectomy group was 14.2% in this study and it was 12.9% in the study of Hioki et al.(23). It was 0% in the patients who continued with alternative chemotherapy according to the result of response test and Badgwell et al.(22) also reported the same figure. Although research methods, difference between the group of patients and treatment methods were rather different in all those studies, the survival rate in this study was similar to the other studies overall.

When gastric cancer patients had unexpected peritoneal seeding after exploration, it was inevitable to close without any procedure. However, the researchers in this study tried to do gastrectomy and gastrectomy with other excision, peritonectomy and D2 above lymph node dissection as long as possible. Kwon(24) and Seo et al.(25) claimed that radical curability could be achieved by gastrectomy and removal of metastasis when the stage of peritoneal seeding was in P1 and Hioki et al.(23) claimed the improvement of the prognosis can be also expected by gastrectomy when the peritoneal seeding was not progressed any further P2. Even the stage of P3, Yonemura et al.(20) did induction chemotherapy to 61 patients with P3 and they claimed that 50% of those patients, that is 30 patients in number, were operated gastrectomy additionally. Like this, Pollock and Roth(26) pointed out that removal of primary tumor reduced the obstruction, bleeding, perforation and ascites caused by the primary tumor and made patients more comfortable. It also increases the efficacy of chemotherapy by reducing the size of tumor and there is immunological benefits by reducing the level of body metabolism and cytokine, the immunosuppressant that produced by tumors.

It is necessary to have clear plans for the methods and the time of response tests and the period of chemotherapy because the response to chemotherapy is an important variable even though chemotherapy is performed primarily and it is important to judge the possible time of radical gastrectomy. The period of chemotherapy in primary chemotherapy of gastric patients with peritoneal seeding is thought to be varied depending on the response to the chemotherapy. Considering the experience of the researchers in this study, some patient were qualified to have gastrectomy just after twice of chemotherapy with quick response and some of the others showed more gradual improvement over the 12 month period and finally were able to have the operation. Yonemura et al.(20) also said between 2 times and 6 times of chemotherapy were carried out depending on the patients and Yoon et al.(27) said between 3 times and 7 times of chemotherapy were carried out prior to gastrectomy which showed that the period of chemotherapy can be varied.

Because the prognosis of the primary chemotherapy group was better than that of the primary gastrectomy group, if the reduction of tumor is achieved by chemotherapy as happened in 16 out of 33 patients in the primary chemotherapy group, it is expected to increase the possibility of radical gastrectomy and the subsequent survival rate by lowering the disease stage.

Generally, gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding receive primary chemotherapy without consideration of primary gastrectomy. But, someone who does not respond to primary chemotherapy should receive primary gastrectomy to improve prognosis.

More researches regarding appropriate primary treatments for the patient with peritoneal seeding are thought to be required because it is possible that primary gastrectomy might be more beneficial for them in terms of the prognosis. Therefore, it is necessary to compare between the efficacy of primary chemotherapy and primary gastrectomy with well-designed prospective randomized clinical study.

There are some limitations in this study. First of all, because the size and the depth of primary lesion, Borrmann's type and the level of affected lymph node were largely different, there can be a lack of consideration on these factors. Additionally, it can be less objective to judge the conglomeration status that makes impossible to operate gastrectomy when the decision is made to do primary gastrectomy. Finally, there is a possibility for subjective interference when the response to chemotherapy was evaluated with the results of gastroscopy, abdominal CT and PET because the unique Korean standard and the international standard to judge the response of chemotherapy are ambiguous. Hence, the objective and detailed standard to judge the response of chemotherapy in gastric cancer is necessary. Currently, the combination chemotherapy is the most commonly used in chemotherapy for gastric cancer and the formula of this vary depending on clinician. As a result, it is not feasible to decide a treatment depending on the response after having chemotherapy under circumstances where there is no objectification for the formula.

Although it is difficult to generalize the results of this study, it is thought to be beneficial to perform gastrectomy actively when feasible.

To improve prognosis of gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding, when these patients receive primary chemotherapy, it is important to actively consider gastrectomy, depending on the response to chemotherapy.

It is also necessary to make comparison between the efficacy of primary chemotherapy and that of primary gastrectomy through well-designed prospective randomized clinical study in order to establish the treatment guidance for the gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding.

References

1. Wisbeck WM, Becher EM, Russell AH. Adenocarcinoma of the stomach: autopsy observations with therapeutic implications for the radiation oncologist. Radiother Oncol. 1986; 7:13–18. PMID: 3775075.

2. Landry J, Tepper JE, Wood WC, Moulton EO, Koerner F, Sullinger J. Patterns of failure following curative resection of gastric carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990; 19:1357–1362. PMID: 2262358.

3. Gunderson LL, Sosin H. Adenocarcinoma of the stomach: areas of failure in a re-operation series (second or symptomatic look) clinicopathologic correlation and implications for adjuvant therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1982; 8:1–11. PMID: 7061243.

4. Yonemura Y, Fujimura T, Fushida S, Takegawa S, Kamata T, Katayama K, et al. Hyperthermo-chemotherapy combined with cytoreductive surgery for the treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. World J Surg. 1991; 15:530–535. PMID: 1891941.

5. Ryu KW, Mok YJ, Kim SJ, Kim CS. Prognostic factors in advanced gastric cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2000; 59:786–792.

6. Chu DZ, Lang NP, Thompson C, Osteen PK, Westbrook KC. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in nongynecologic malignancy. A prospective study of prognostic factors. Cancer. 1989; 63:364–367. PMID: 2910444.

7. Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, Beaujard AC, Rivoire M, Baulieux J, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer. 2000; 88:358–363. PMID: 10640968.

8. Wilke H, Preusser P, Fink U, Gunzer U, Meyer HJ, Meyer J, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy in locally advanced and nonresectable gastric cancer: a phase II study with etoposide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1989; 7:1318–1326. PMID: 2769330.

9. D'Ugo D, Persiani R, Rausei S, Biondi A, Vigorita V, Boccia S, et al. Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and effects of tumor regression in gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006; 32:1105–1109. PMID: 16930932.

10. Sugarbaker PH, Yonemura Y. Clinical pathway for the management of resectable gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding: best palliation with a ray of hope for cure. Oncology. 2000; 58:96–107. PMID: 10705236.

11. Stern JL, Denman S, Elias EG, Didolkar M, Holyoke ED. Evaluation of palliative resection in advanced carcinoma of the stomach. Surgery. 1975; 77:291–298. PMID: 1129702.

12. Kim HI, Ha TK, Kwon SJ. Prognostic factors in gastric cancer patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Gastric Cancer. 2010; 10:126–132.

13. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998; 1:10–24. PMID: 11957040.

14. Ikeguchi M, Oka A, Tsujitani S, Maeta M, Kaibara N. Relationship between area of serosal invasion and intraperitoneal free cancer cells in patients with gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 1994; 14:2131–2134. PMID: 7840512.

15. Sugarbaker PH. Peritonectomy procedures. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003; 12:703–727. PMID: 14567026.

16. Kuramoto M, Shimada S, Ikeshima S, Matsuo A, Yagi Y, Matsuda M, et al. Extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage as a standard prophylactic strategy for peritoneal recurrence in patients with gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009; 250:242–246. PMID: 19638909.

17. Hunerbein M, Rau B, Hohenberger P, Schlag PM. Th e role of staging laparoscopy for multimodal therapy of gastrointestinal cancer. Surg Endosc. 1998; 12:921–925. PMID: 9632861.

18. Song SC, Lee SL, Cho YK, Han SU. The role and efficacy of diagnostic laparoscopy to detect the peritoneal recurrence of gastric cancer. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2009; 9:51–56.

19. Shimizu H, Imamura H, Ohta K, Miyazaki Y, Kishimoto T, Fukunaga M, et al. Usefulness of staging laparoscopy for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Today. 2010; 40:119–124. PMID: 20107950.

20. Yonemura Y, Bandou E, Sawa T, Yoshimitsu Y, Endou Y, Sasaki T, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006; 32:661–665. PMID: 16621433.

21. Glehen O, Gilly FN, Arvieux C, Cotte E, Boutitie F, Mansvelt B, et al. Association Française de Chirurgie. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: a multi-institutional study of 159 patients treated by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010; 17:2370–2377. PMID: 20336386.

22. Badgwell B, Cormier JN, Krishnan S, Yao J, Staerkel GA, Lupo PJ, et al. Does neoadjuvant treatment for gastric cancer patients with positive peritoneal cytology at staging laparoscopy improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008; 15:2684–2691. PMID: 18649106.

23. Hioki M, Gotohda N, Konishi M, Nakagohri T, Takahashi S, Kinoshita T. Predictive factors improving survival after gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Surg. 2010; 34:555–562. PMID: 20082194.

24. Kwon SJ. Investigation of long-term survivors with stage IV gastric cancer. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2002; 2:157–162.

25. Seo YJ, Bae JM, Kim SW, Kim SW, Song SK. Different clinical outcomes of stage IV gastric cancer according to the curability of surgery. J Korean Surg Soc. 2009; 77:170–176.

26. Pollock RE, Roth JA. Cancer-induced immunosuppression: implications for therapy? Semin Surg Oncol. 1989; 5:414–419. PMID: 2688031.

27. Yoon SY, Kim MG, Oh ST. Th e impact of preoperative chemotherapy on the surgical management of unresectable gastric cancer. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2009; 9:269–274.

Fig. 1

Patients selection algorithm for the treatment of gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding.

Fig. 2

Survival curves for gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding according to primary treatment.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download