Abstract

Objectives

This study considered whether there could be a change of mortality and length of stay as a result of inter-hospital transfer, clinical department, and size of hospital for patients with organophosphates and carbamates poisoning via National Patients Sample data of the year 2009, which was obtained from Health Insurance Review and Assessment Services (HIRA). The utility and representativeness of the HIRA data as the source of prognosis analysis in poisoned patients were also evaluated.

Methods

Organophosphate and carbamate poisoned patients' mortality and length of stay were analyzed in relation to the initial and final treating hospitals and departments, as well as the presence of inter-hospital transfers.

Results

Among a total of 146 cases, there were 17 mortality cases, and the mean age was 56.8 ± 19.2 years. The median length of stay was 6 days. There was no inter-hospital or inter-departmental difference in length of stay. However, it significantly increased when inter-hospital transfer occurred (transferred 11 days vs. non-transferred 6 days; p = 0.037). Overall mortality rate was 11.6%. The mortality rate significantly increased when inter-hospital transfer occurred (transferred 23.5% vs. non-transferred 7.0%; p = 0.047), but there was no statistical difference in mortality on inter-hospital and inter-department comparison at the initial treating facility. However, at the final treating facility, there was a significant difference between tertiary and general hospitals (5.1% for tertiary hospitals and 17.3% for general hospitals; p = 0.024), although there was no significant inter-departmental difference.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that hospital, clinical department, length of stay, and mortality could be analyzed using insurance claim data of a specific disease group. Our results also indicated that length of stay and mortality according to inter-hospital transfer could be analyzed, which was previously unknown.

The Republic of Korea (ROK) adopted a fee for service system by a single health care agent, the national health insurance service. Every detail about practice, medication, and diagnosis of all patients is transmitted to the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Services (HIRA) [1]. In May 2012, HIRA provided the National Patients Sample (NPS) data of the year 2009, named HIRA-NPS-2009, which contains about 13% of the hospitalized patient data and 1% of outpatient data with national representativeness [2]. HIRA-NPS-2009 was extracted with stratified and systematic sampling methods according to sex and age group among all patients who used medical services in 2009. It included every detail of the medical care services and drug prescriptions of the sample patients. The representativeness of this sample was verified by HIRA and 5 other medical associations in the ROK [2].

Recently, a few papers have been published based on data from HIRA-NPS-2009 [3-5]. Park et al. [3] mainly focused on epidemiology, and others investigated the incidence of unusual diseases [4,5]. However, we thought that it could also be possible to analyze inter-hospital transfer because HIRA-NPS-2009 contains every detailed personal history of the utilization of medical services.

As many as 3 million cases of organophosphate and carbamate intoxication occur around the globe each year [6,7], and the problem is particularly prevalent in agricultural countries and developing countries [8,9]. The ROK is no longer a developing country, but the occurrence of organophosphate and carbamate intoxication in the ROK is increasing nevertheless [10,11]. The mortality of organophosphate and carbamate intoxication is still around 10% to 20% [12-14], and it is higher when compared with other types of drug intoxication [15].

Many articles about organophosphate and carbamate intoxication have been published, but data has been limited because it was only a part of intoxication of agricultural chemicals or overall drugs or a part of death statistics [10,11]. Clinical studies have been based on a single hospital or targeted areas [16] and mainly in regards to the treatment in hospital or prognostic factors [17-19]. There also has been a lack of research on the effects of hospitals and departments.

Unlike other types of intoxication, there are definite antidotes for organophosphate and carbamates exposure. The mortality of these disease entities could be lowered with sufficient use of atropine, 2-pyridine aldoxime methyl chloride (2-PAM, known as pralidoxime) and vigorous airway management if used from the early stage of their occurrence. Unfortunately, these treatments are inevitably stopped or interrupted during inter-hospital transfer. Inter-hospital transfers frequently occur in the cases of severely ill patients. The majority of inter-hospital transfers are done so that the patient can receive the proper treatment; however, it is well known that mortality and morbidity were inversely increased for transferred patients [20].

We therefore investigated changes in mortality and length of stay as a result of inter-hospital transfer, clinical department, and size of hospital where patients were admitted using HIRA-NPS-2009 in organophosphate and carbamate poisoning. The utility and representativeness of the HIRA data as the source of prognosis analysis of intoxicated patients were also evaluated.

HIRA-NPS-2009 includes 3 types of diagnosis fields, namely, main diagnosis, sub-diagnosis, other diagnosis. First, patient records with the diagnosis code T60.0, which means organophosphate and carbamate intoxication in the International Classification of Diseases tenth revision (ICD-10), were extracted from HIRA-NPS-2009 by searching all 3 diagnosis fields. Second, we excluded the records of patients treated in out-patient clinics because this might be preventive treatment for chronic exposure. Third, we excluded the records of patients who did not administer both atropine and 2-PAM or atropine alone during the first hospital day by analyzing drug administration and treatment records because this is mandatory treatment for acute organophosphate and carbamate poisoning. Fourth, we excluded the acute poisoned patients' unrelated records, such as out-patient clinic visit for regular follow-up after discharge or hospital admissions because of other diseases.

We used the term 'inter-hospital transfer' where a patient was discharged from one hospital and admitted to another hospital with the same diagnosis code T60.0 within the same day. When patients were transferred more than two times, we only took the initial and the final admitting hospitals and departments into consideration. We used the term 'mortality' for patients' whose discharge result field was "death".

We categorized patients by the level of admitting hospitals. In the ROK, hospitals are subdivided into tertiary hospitals, general hospitals, hospitals, and geriatric hospitals by law, according to the size of the hospital and the composition of health care providers. Tertiary hospitals are the highest level of hospital class in the ROK certified by the government. The requirements of these hospitals are fixed by law. General hospitals must have over 100 beds and an emergency room, whereas hospitals must have over 30 beds and an emergency room is optional. Geriatric hospitals must have over 30 beds and are specialized for geriatrics or chronically ill patients.

There were various admitting departments including emergency medicine, internal medicine, general surgery, family medicine, chest surgery, psychiatry, and pediatrics. Since emergency medicine and internal medicine were the main admitting departments, the rest were rolled into one category, as other departments.

We analyzed age, sex, initial and final admitting hospitals and departments, transfer, length of stay, and mortality of organophosphate and carbamate intoxication patients. We performed a chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were completed using SAS ver. 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

HIRA-NPS-2009 contains 27,320,505 medical records of 1,116,040 patients. Among them, medical records coded T60.0 were 277 records from 179 patients. Excluded cases included the following: 1) preventative treatment cases at out-patients clinics (11 patients' 18 records), 2) cases in which there was no administration of both atropine and 2-PAM or atropine alone were (22 patients' 42 records), 3) acute poisoned patients' records of out-patients clinic follow-up visits after discharge, treatments at out-patients' clinics, or hospital administration because of other diseases (56 records) (Figure 1). After excluding these records, we were left with 160 records from 146 patients with acute organophosphate and carbamate intoxication (Table 1).

The majority were male (99 males and 47 females, p < 0.001). There were 17 mortality cases (12 males and 5 females), but mortalities were not distinguished from each other. The mean age of acute organophosphate and carbamate intoxication was 56.8 ± 19.2 years, and it was 56.2 ± 1.75 years for males and 58.1 ± 3.3 years for females. The median length of stay was 6 days (interquartile range [IQR], 3-16), and it was 6 days (IQR, 3-16) for males and 5 days (IQR, 3-15) for females (Table 1).

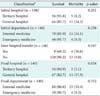

A comparison of mortality rates according to initial and final treating hospital classes and clinical departments is shown Table 2. According to these results the majority of patients were treated in tertiary hospitals and general hospitals and departments of internal medicine and emergency medicine. Therefore, further analysis of length of stay and mortality were performed for those categories.

The median length of stay was 6 days (IQR, 3-6). When sorted by the initial admitting hospital, it was found to be 7 days (IQR, 4-20) for tertiary hospitals and 5 days (IQR, 3-11) for general hospitals. When sorted by the initial admitting department, it was 6 days (IQR, 3-22) for emergency medicine departments and 6 days (IQR, 3-18) for internal medicine departments. When sorted by the final admitting hospital, it was 6 days (IQR, 3-18) for tertiary hospitals and 6 days (IQR, 3-13) for general hospitals. When sorted by the final admitting department, it was 6 days (IQR, 3-22) for emergency medicine departments and 6 days (IQR, 3-12) for internal medicine departments. There was no difference in inter-hospital and inter-departmental length of stay (Table 3).

Overall, the mortality rate was 11.6%. When sorted by the initial admitting hospital, the mortality rate was 8.2% for tertiary hospitals and 14.3% for general hospitals. It was 8.3% for emergency medicine and 13.2% for internal medicine when sorted by the initial admitting department. When sorted by the final admitting hospital, the mortality rate was 5.1% for tertiary hospitals and 17.3% for general hospitals. The mortality rate was 9.3% for emergency medicine and 13.4% for internal medicine when sorted by the final admitting department. According to the final admitting hospital, the mortality rate showed a significant difference between tertiary and general hospitals (p = 0.024). There was no inter-departmental mortality difference by the final admitting department (Table 4).

Under the healthcare system in the ROK, HIRA gathers the entire patient's circumstantial information of medical treatment and diagnosis [1]. As this data is mainly used for hospital reimbursement methods, it has been widely thought that there are limitations to the use of this data for clinical research. However, papers using HIRA-NPS-2009 are increasingly being reported. Although it is derived from medical insurance claim data, we expect that studies could produce considerable clinical results based on these data because medical insurance reimbursement is basically founded on a fee for service delivery system in the ROK.

Though some studies just investigated the incidence of specific diseases [4,5], the research by Park et al. [3] analyzed the correlation between the epidemiology of head trauma patients and the frequency of conducting computed tomography among those patients. They also demonstrated that epidemiologic analysis could be conducted using the medical insurance claim database.

This study demonstrated that hospital, clinical department, length of stay, and mortality could be analyzed using insurance claim data in a specific disease group. This study also indicated that length of stay and mortality according to inter-hospital transfer could be analyzed, which was previously unknown.

We considered the possibility that the analysis of a rare disease entity like the one considered in this study using HIRA-NPS could be inappropriate because of the problem of representativeness. However, HIRA insists that HIRA-NPS has representativeness even for rare disease entities [2]. Therefore, we recommend a comparison study using all of the HIRA claims data.

From a clinical point of view, our study is the first attempt to compare mortality and length of stay according to the grade of hospital and clinical department at the beginning and the end of treatment and inter-hospital transferred patients using a national representative patient sample. The mortality and length of stay were not influenced by the initial hospital and initial admitting department, but we ascertained that a higher level of the final treatment hospital corresponded to lower mortality. When inter-hospital transfer occurred, length of stay and mortality increased. This means that continuity of treatment was interrupted during transfers.

Actually, the majority of organophosphate and carbamate intoxication patients suffer from mental disorientation, unstable vital signs, and difficulty in respiration due to secretion. These patients need proper airway management with or without ventilator therapy, arrhythmogenic drugs like atropine, and appropriate monitoring. However, during interhospital transfer, the aforementioned patient conditions and treatments are regarded as risk factors [21]. When transferring patients in a high risk, the group ICU vehicle is recommended with a nurse and doctor as ambulance staff [21,22]. Unfortunately, in the ROK, it is uncommon to transfer critically ill patients with proper equipment and manpower.

A strategy and guideline for transfer appear to be needed [20]. According to one research in the ROK, the transfer rate of intoxication patient was reduced from 22% to 9% when the emergency medicine department was the initial admitting department compared to the internal medicine department [23]. In our study, the higher the level of hospital, the more emergency medicine department was involved in treatment, although it does not have a statistically significant effect on prognosis. It might be according to treatment pattern. Nowadays most hospitals have departments of emergency medicine, so rapid treatment could be given. Organophosphate and carbamate poisoning requires initial vigorous treatment, and departments of emergency medicine can apply appropriate treatment at a very early stage. Also, we verified that patients who finished their treatment at higher level hospitals had a good prognosis. These results are probably explained by the greater resources of those hospitals.

Unfortunately, we could not analyze some factor influencing mortality. One of them is the type of inter-hospital transfer. HIRA-NPS has anonymized patients' identification and also anonymized facilities' identification, but it only contains hospital classifications; thus, we could not analyze whether inter-hospital transfer was within a region or to a distant region. We were able to analyze according to level of hospital classes, however, this classification by the law does not necessarily reflect the actual ability of a given hospital to treat poisoned patients. Actually, in the ROK, some general hospitals might offer more appropriate treatment for poisoned patients than tertiary hospitals so we didn't analyze this.

Also, there were a small number of mortality cases, so we could not analyze the influences of co-morbidity. However, initial vigorous treatment like atropine and 2-PAM administration as well as airway management are the key of treatments for organophosphate and carbamate poisoning; the major cause of mortality of these patients was inappropriate initial treatment [6,7,13,15]. Analysis of co-morbidity is not mandatory for early stage mortality, but some of these patients had very long length of stay; in these cases, comorbidity might have had an influence. For this reason, we suggest further study to investigate the influences of comorbidity using all of the HIRA claims data.

In conclusions, length of stay and mortality rate significantly increased when inter-hospital transfer occurred. There was no statistical difference in mortality on inter-hospital and inter-department comparison at the initial treating facility. However, at the final treating facility, there was a significant difference between tertiary and general hospitals, although there was no significant inter-departmental difference. Furthermore, we demonstrated that hospital, clinical department, length of stay, and mortality could be analyzed using insurance claim data of a specific disease group. The results also indicated that length of stay and mortality according to inter-hospital transfer could be analyzed, which was previously unknown.

HIRA have gathered insurance claim data that include medication, treatment, operation, diagnosis, and so on. Most toxicology studies using these data have been based on a single hospital or small hospital groups until now. We think there is great opportunity for research using the HIRA data because the number of patient cases is huge. Furthermore, we could find much more information if other government operating registry systems, for example, the National Emergency Department Information System were also available. Because HIRA-NPS was based on insurance claim data, we could not see the result of clinical investigation but also time and order of specific medication and treatment. It could be a major limitation of studies based on HIRA-NPS data.

From a clinical perspective, this study has the following limitations: 1) data analysis was not based on clinical data but on insurance claims data; 2) due to the limited data, factors that generally affect the prognosis could not be evaluated-these include volume of ingestion, toxicity, ingestion to hospital time, antidote and treatment method; 3) we could not discriminate organophosphates and carbamates because the diagnosis code was combined into one category as T60.0; and 4) co-morbidity could act as a confounding factor, but we could not analyze it because of limited data.

Figures and Tables

Table 2

Comparison of mortality rate according to initial and final treating hospitals and departments (n = 146)

Table 3

Comparison of length of hospitalization according to initial and final treating hospitals, departments and inter-hospital transfer (n = 146)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Inje University, 2011 and presented at the Pan-Pacific Emergency Medicine Congress 2012. We used the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service (HIRA)' National Patient Sample 2009 (HIRA-NPS-2009-001) for this study, but the results have no concern with the Ministry of Health and Welfare and HIRA.

References

1. Park YT, Yoon JS, Speedie SM, Yoon H, Lee J. Health insurance claim review using information technologies. Healthc Inform Res. 2012; 18(3):215–224.

2. Kim RY. Introduction of Health Insurance Review and Assessment services' national patients sample. HIRA Policy Trend. 2012; 6(5):37–47.

3. Park SY, Jung JY, Kwak YH, Kim DK, Suh DB. A nationwide study on the epidemiology of head trauma and the utilization of computed tomography in Korea. J Trauma Inj. 2012; 25(4):152–158.

4. Yuk JS, Kim YJ, Hur JY, Shin JH. Incidence of Bartholin duct cysts and abscesses in the Republic of Korea. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013; 122(1):62–64.

5. Yuk JS, Kim YJ, Hur JY, Shin JH. Association between pregnancy and acute appendicitis in South Korea: a population-based, cross-sectional study. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013; 85(2):75–79.

6. Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, Eddleston M, Gunnell D. Deaths from pesticide poisoning: a global response. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 189:201–203.

8. Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Phillips MR, Konradsen F. The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2007; 7:357.

9. Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. QJM. 2000; 93(11):715–731.

10. Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Injury surveillance report 2011 [Internet]. Cheongwon: Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention;2012. cited at 2013 Mar 13. Available from: http://injury.cdc.go.kr/.

11. Statistics Korea. Annual report on the causes of death statistics 2011 [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2012. cited at 2013 Mar 13. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/.

12. Sung AJ, Lee KW, So BH, Lee MJ, Kim H, Park KH, et al. Multicenter survey of intoxication cases in Korean emergency departments: 2nd annual report, 2009. J Korean Soc Clin Toxicol. 2012; 10(1):22–32.

13. Shin KC, Lee KH, Park HJ, Shin CJ, Lee CK, Chung JH, et al. Respiratory failure of acute organophosphate insecticide intoxication. Tuberc Respir Dis. 1999; 46(3):363–371.

14. Ko Y, Kim HJ, Cha ES, Kim J, Lee WJ. Emergency department visits due to pesticide poisoning in South Korea, 2006-2009. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012; 50(2):114–119.

15. Tsao TC, Juang YC, Lan RS, Shieh WB, Lee CH. Respiratory failure of acute organophosphate and carbamate poisoning. Chest. 1990; 98(3):631–636.

16. Na BH, Oh DR, Hwang JI, Lim KW, Yu SJ, Park IY, et al. The regional analysis of drug poisoning in emergency room. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 1995; 6(1):107–112.

17. Kim JY, Jung HM, Kim JH, Han SB, Kim JS, Paik JH. Prognostic factors of acute poisoning in elderly patients. J Korean Soc Clin Toxicol. 2011; 9(2):81–87.

18. Lee MJ, Kwon WY, Park JS, Eo EK, Oh BJ, Lee SW, et al. Clinical characteristics of acute pure organophosphate compounds poisoning: 38 multi-centers survey in South Korea. J Korean Soc Clin Toxicol. 2007; 5(1):27–35.

19. Jokanović M. Medical treatment of acute poisoning with organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides. Toxicol Lett. 2009; 190(2):107–115.

20. Warren J, Fromm RE Jr, Orr RA, Rotello LC, Horst HM. American College of Critical Care Medicine. Guidelines for the inter- and intrahospital transport of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32(1):256–262.

21. Etxebarría MJ, Serrano S, Ruiz Ribo D, Cia MT, Olaz F, Lopez J. Prospective application of risk scores in the interhospital transport of patients. Eur J Emerg Med. 1998; 5(1):13–17.

22. Markakis C, Dalezios M, Chatzicostas C, Chalkiadaki A, Politi K, Agouridakis PJ. Evaluation of a risk score for interhospital transport of critically ill patients. Emerg Med J. 2006; 23(4):313–317.

23. Choi OK, Yoo JY, Kim MS, Jung KY. Acute drug intoxication in ED of urban area. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 1995; 6(2):324–329.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download