Abstract

Objectives

This study was designed to compare the data from the emergency department syndromic surveillance system of Korea in detection and reporting of acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) with the data from the Korea Food and Drug Administration. And to offer fundamental materials for making improvements in current surveillance system was our purpose.

Methods

A study was conducted by reviewing the number of cases reported as acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) from the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention between June, 2002 and July, 2008. And the data were compared with the number of mass food poisoning cases during the same period, reported from the Korea Food and Drug Administration. The difference between two groups was measured and their transitions were compared.

Results

The emergency department

syndromic surveillance system's reports of the numbers of acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) cases were different from the transition of mass food poisonings, reported by the Korea Food and Drug Administration. Their reports were not accurate and they could not follow the trends of increase in mass food poisonings since 2002.

Conclusions

Current problems in the emergency department syndromic surveillance system in Korea are mostly related to inaccuracies of daily data reporting system. Manual data input by the reporters could play a big role in such inaccuracies. There need to be improvements in the ways of reporting data, such as automated information transport system linking electronic medical record.

Syndromic surveillance system is a method detecting the disease outbreak by means of real-time continuous monitoring, measurement, gathering, analysis and interpretation of data drawn from various sources regarding specific disease. Serving as a frontline vigilance, the main purpose of this system is to allow us to predict the disease outbreak before its spread and to prepare for proactive measures [1]. Accurate identification of the exceeding number of patients in target syndrome during certain period or geographic region, with comparing the historical data gathered previously, is the main factor that allows prediction of disease outbreak before it is detected by other traditional methods.

The emergency department syndromic surveillance system (EDSS) has been designed in the era of heightened concerns of bioterrorism attack, water and foodborne diarrheal disease and respiratory disease including influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In the year 2002, the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) implemented the EDSS, the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network, which has been run by emergency departments of 125 designated hospitals nationwide. Five target syndromes including acute rash syndrome, acute neurologic syndrome, acute hemorrhagic fever syndrome, acute respiratory syndrome and acute diarrheal syndrome (sporadic type and mass type) are monitored (Table 1), and emergency departments in designated hospitals are obligated to report the number of corresponding cases of syndromic surveillance daily through the website (http://bioterrorism.cdc.go.kr/) and online reports. The target subjects including infectious disease are not only the potential bioterrorism but also they are capable of spreading mass type diarrheal illness including food poisoning, bacterial dysentery, water and foodborne infectious disease and acute diarrheal syndrome which is divided into sporadic type and mass type [2].

The city, county and borough public health centers collect daily reports from emergency departments in their districts, and urge those who didn't report their daily data to complete their work. And the city and province public health and hygiene policy departments also monitor the emergency departments' reporting status in their regions and continuously analyze the disease outbreak (Figure 1). And whenever bioterrorism-like patients' emergence or epidemics are suspected, they urge the regional public health center to execute epidemiologic study, and also direct and inspect their investigations [2].

The main problem in current EDSS is lack of accuracy in their reports. Although the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network provides the definition of subject syndromes including symptoms and signs, the frequent changes in the reporters and their subjective decisions could lead the reports into a lack of accuracy, and therefore exert a bad influence on reliability of the surveillance system. Also, since the reports are not utterly mandatory, though it is obligatory, the reporters may not allot sufficient times and efforts, which could also have adverse effect on reliability [3]. To improve these problems in the EDSS, diverse studies and efforts were carried out worldwide. Application of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9-CM) instead of chief complaint, combination of both ICD-9-CM and chief complaint in data collection and introduction of the Real-time Outbreak and Disease Surveillance (RODS) are their examples [4,5]. But there was no change in domestic EDSS in the way of syndrome reporting method since its introduction in 2002, except adopting the enhanced surveillance system during the Universiade Games in 2003 and the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation Meeting in 2005.

This study was performed to analyze the accuracy of EDSS by comparing the data from the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA), and to offer fundamental materials for making improvements in current surveillance system.

In this study, we investigated the reporting processes of target syndromes from Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network and Food Poisoning Statistical System respectively, and compared each data and their trends.

EDSS database is constructed and displayed at Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network website (http://bioterrorism.cdc.go.kr/) after gathering the reports from each emergency departments participating in the syndromic surveillance. We obtained the number of cases and total patients reported as acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) from June, 2002 to July, 2008. The Korean CDC monitors daily reports from 125 emergency departments nationwide to detect the emergence of 5 syndromes which can be used as bioterrorism attack, and in case of necessity, request the patient's specimen and laboratory analysis. Every morning before 10 a.m., designated emergency departments must report the number of patients of subject syndromes, visited between 9 a.m. the day before and 9 a.m. of the day. In the absence of the reporter, a person in charge or a proxy must report instead, and even though there was no patient of subject syndromes, he or she must report as zero. Especially, in case of acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type), the reporters must notify their emergence immediately, and the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network indicates the total number of cases, not the number of individual patients. Reports are done through the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network website. If internet is not available, the reporter must fill out the form and send it to district public health center by fax, and when bioterrorism is highly likely, he must telephone immediately.

We obtained the number of mass food poisoning cases from the Food Poisoning Statistical System (http://e-stat.kfda.go.kr/) of the KFDA during the same period, June, 2002 to July, 2008 as the data of acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) were acquired from the Korean CDC. The Food Poisoning Statistical System of the KFDA reports the number of cases and patients classified by periods, regions, causative organisms and causative facilities. Irrespective of the types of medical facility, according to the Food Sanitation Act, Article 67, Clause 1-3, doctors must report the case to the district public health center whenever they diagnose any mass food poisoning patients or examine who are suspicious to be so, and the head of public health center must report it to the provincial governor, and the provincial governor must report it to the Ministry of Health and Welfare minister and the director of the KFDA. These rules are mandatory and to those who violate the rules, fine is imposed. The KFDA reports mass food poisoning statistics on the basis of public health centers' report data.

The number of mass food poisoning cases from June, 2002 to July, 2008 according to the KFDA and the number of acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) cases from the Korean CDC during the same period are tabulated (Table 2). The differences between the number of mass food poisoning cases from the KFDA and acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) cases from the Korean CDC showed -40 cases in 2002, 60 cases 2003, 56 in 2004 and 73 in 2005, but the differences were increased to 233 in 2006, 488 in 2007 and 152 in 2008 till July. The difference between the number of mass food poisoning cases and acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) cases according to their geographic distributions showed that there were large differences during 2007 in Seoul, Incheon, Busan, Gyeonggi, North Gyeongsang, South Chungcheong and North Jeolla, and during 2006 in Seoul and Incheon. During 2004, Seoul, Incheon, Daejeon and Jeju, and during 2002, districts except Gwangju, North Chungcheong, North Gyeongsang and South Gyeongsang, the number of acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) cases were higher than that of mass food poisoning cases and their differences showed negative values. In the year 2002, when the EDSS was first introduced, the values of difference in most districts were negative. However, in 2007 it turned to positive in all districts. Especially in Gyeonggi province, the difference was 113 showing much larger number from the KFDA than the Korean CDC.

To investigate the large differences between mass food poisoning cases from the KFDA and acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) cases from the Korean CDC, monthly changes during 2007 were analyzed and schematized into histogram (Figure 2). In March 2007, the number of mass food poisoning cases from the KFDA was 41, increased from 31 in January and 28 in February. On the contrary, none of the cases were reported from the Korean CDC. During April and May, the KFDA reports were increased from 42 to 65, but the Korean CDC showed no increase, rather, the number was decreased, and despite 32 cases from the KFDA in November, none was reported from the Korean CDC.

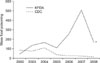

The Food Poisoning Statistical System of the KFDA showed annual increase in mass food poisonings (Figure 3). Even though the results were collected until July 2008, this increase could be confirmed. On the contrary, the number of cases reported as acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) from the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network of the Korean CDC was decreased. On the other side, during the early days of the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network, their results were higher than those from the Food Poisoning Statistical System of the KFDA, which could be resulted as active participation during early days of the system's introduction.

The KFDA analyzed the outbreaks of food poisoning in the last seven years (2002-2008) and revealed the results. The food poisoning outbreaks were increased annually since 2003, and increase in school cafeterias and dining out, and change of climate from temperate zone to subtropical zone were considered to be the cause [6]. For the last five years, 75.6% of the total food poisonings were related to cafeterias and restaurants dealing sea foods such as fishes and shellfishes. School cafeterias had outbreaks during March and September beginning of the semester, and restaurants, between May and September when the temperature has risen. Pathogenic E.coli, salmonella, staphylococcus, vibrio, campylobacter jejuni and norovirus were the leading organisms of food material contamination and poor personal hygiene. Especially, the food poisonings during winter period, norovirus accounted for 42% [6]. Despite this increasing tendency, the reported cases of acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) by the EDSS were decreased instead. Besides, comparing the reports from the KFDA in 2007, the reports were unreasonably insufficient to enable early detection and alerting an early warning system of food poisonings.

The original purpose of the EDSS is to integrate the number of symptoms requiring emergency care during the average year and create the standard number of patients, then when the subject syndromic patients exceed 2 to 3 standard deviation of the standard patient, alert an early warning system, at the same time discriminate between true prevalence of the disease and errors of data input or phenomenon of natural increase due to weather or time differences. Also, if necessary, perform epidemiologic study and inform those who work in the emergency departments to be prepared for the disease outbreak. Nowadays, various countries including those of North America have implemented this surveillance system [7-10].

What we have learned from this study was that there are substantial discrepancies between the data reported from the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network and the actual disease outbreaks. Of course, there are limitations that participating emergency departments in the syndromic surveillance is limited to 125 organs and that some degree of patients might seek for medical services besides emergency departments, such as private clinics or outpatient departments. But considering the fact that the data from the KFDA and the Korean CDC are both from the same population, and that both groups should at least follow the same trends of rise or fall, the study results are not comprehensible. After all, the factor that can cause these discrepancies, which the Korean EDSS is currently facing, is that the report rates could be dependant on the reporter's education level and their wills to report [3]. Meanwhile the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network reveals every emergency department's report rates and their rankings in the website and forces them to actively participate. The city, county and borough public health centers also urge those emergency departments who haven't submitted their daily reports. These measures may increase the report rates, but they can not improve their accuracies. After all, limitations of the Korean EDSS including lack of compulsory manners, not being automatically linked to electronic medical record, and the different reporting process in data reporting system between the Korean CDC and the KFDA, might have brought out the large discrepancies in our study.

EDSS was introduced as the epidemics of infectious diseases and bioterrorismal threats were issued globally. If performed effectively, it could offer great opportunities for early detection and preparedness for the target diseases or accidents like bioterrorism. It is crucial to systematize its adoption and application, and successive amelioration of current system is indispensable. Attempts to improve accuracies in the EDSS were made. Beitel et al. [4], in their study of pediatric population, reported that using the ICD-9 code alone or in combination with the chief complaint code improved identification of respiratory syndromes than using the chief complaint code alone, and Fleischauer et al. [5] reported the ICD-9 code provides better performance than the chief complaint code in the EDSS. But the limitations in using the diagnostic code are the variance in coding, errors in input, time consumption until the diagnosis being made and changes in the confirmative diagnosis after short term emergency care. On the contrary, using the chief complaint enables early detection, one of the main objects in surveillance system, and therefore numerous medical institute use this code in their surveillance systems [11,12]. Some studies stress on the capability of early detection, and to improve the sensitivity of surveillance system, they modified their preexisting chief complaint codes by adding other chief complaints that were not related to specific disease and were not included previously [4]. Despite diverse attempts in improving syndromic surveillance performance in other countries, the Korean EDSS still maintains the method of inputting data manually to the computer by the reporter's judgment. After all, accurate data couldn't be reported, and the EDSS could not play its role properly.

Our institution developed our own EDSS program named Emergency Room Syndrome Surveillance (Figure 4). Its main purpose was to enable the emergency department administrator to detect early the increase in the number of target syndromes visiting emergency room, and to allow the emergency practitioners for preliminary actions towards the target syndromes, so they could serve as a frontline vigilance in our own hospital. It is automated, real time monitoring system. Data regarding target syndromes are gathered automatically. This process is carried out by collecting the daily numbers of patients' chief complaints which are related to target syndromes, and total number of each syndromic patient is displayed in our electronic medical record system. So whenever the number of target syndromic patient is increased much more than previous data, emergency doctors and nurses can specifically pay attention to the related disease and be prepared. If the program mentioned above were applied to the Korean EDSS, improvement of the accuracy of the system's performance by ameliorating the passive and manual method of daily reports could be expected.

Limitations in this study are first, unable to analyze the collected data in the KFDA according to the medical institutes, second, the Korean CDC reports could not be compared with the data from the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) of the National Emergency Medical Center and third, unable to analyze the accuracy of reporters' performances in each emergency departments. The reason for these limitations is that the law of personal information protection in public institution restricts external institution's survey of data collected by a government agency. If it is possible to analyze overall data from the KFDA and NEDIS of the National Emergency Medical Center, the accuracy of the EDSS will be improved. As NEDIS also gathers information from designated emergency departments nationwide, by comparing the number of input cases between NEDIS and the EDSS, credibility of the reports in each institution could also be analyzed.

During the study period, the cases reported as mass food poisoning from the KFDA was much larger than the data reported as acute diarrheal syndrome (mass type) from the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network of the Korean CDC, and their trends were opposite. After all, due to the data input and reporting manners, which are the major limitations of current Korean EDSS, our surveillance system could not attain its original purpose, early and accurate detection of disease outbreaks.

EDSS is designed to play a key role as frontline supervision in real time monitoring the disease outbreak. Apt role could provide timely actions to cope with the disease, which is essential in dealing with bioterrorism. Buehler et al. [13]. pointed out that the following factors must be fulfilled in achieving effectiveness of the EDSS. First, surveillance system must be highly sensitive, second, the system should have high positive predictive value and third, system needs to be capable of early detection. Current EDSS in Korea has major defect in accuracy of data collecting system, which hampers early detection and preparedness of disease outbreak. Henceforth, to improve reliability, data collection must be automated by linking electronic medical record rather than daily inputting system by the reporters, and further improvements and studies are required.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Diagram of data report flows in the emergency department syndromic surveillance system of Korea.

Figure 2

The number of mass food poisoning cases in 2007. The number of mass food poisoning cases reported by the Food Poisoning Statistical System of the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) and the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network of the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2007.

Figure 3

The number of mass food poisoning cases each year. The number of mass food poisoning cases reported by the Food Poisoning Statistical System of the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) and the Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network of the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) each year.

*Data was calculated until July, 2008.

Figure 4

Computer display of the Emergency Room Syndrome Surveillance (ERSS). ERSS was a computerized program invented in our institution. Automated data collection and displaying the data of target syndromes are shown. This process is carried out by gathering the daily numbers of patients' chief complaints which are related to target syndromes and total number of each syndromic patient is displayed.

References

1. Sosin DM. Syndromic surveillance: the case for skillful investment view. Biosecur Bioterror. 2003. 1:247–253.

2. Anti-Bioterrorism Information Network. Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. cited on 2010 Aug 16. Available from: http://bioterrorism.cdc.go.kr.

3. Cho JP, Min YG, Choi SC. Syndromic surveillances based on the emergency department. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008. 41:219–224.

4. Beitel AJ, Olson KL, Reis BY, Mandl KD. Use of emergency department chief complaint and diagnostic codes for identifying respiratory illness in a pediatric population. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004. 20:355–360.

5. Fleischauer AT, Silk BJ, Schumacher M, Komatsu K, Santana S, Vaz V, Wolfe M, Hutwagner L, Cono J, Berkelman R, Treadwell T. The validity of chief complaint and discharge diagnosis in emergency department-based syndromic surveillance. Acad Emerg Med. 2004. 11:1262–1267.

6. Food poisoning statistical system. Korea Food and Drug Administration. cited on 2010 Aug 16. Available from: http://e-stat.kfda.go.kr.

7. Caudle JM, van Dijk A, Rolland E, Moore KM. Telehealth Ontario detection of gastrointestinal illness outbreaks. Can J Public Health. 2009. 100:253–257.

8. Gangnon R, Bellazzini M, Minor K, Johnson M. Syndromic surveillance: early results from the MARISSA project. WMJ. 2009. 108:256–258.

9. Muscatello DJ, Churches T, Kaldor J, Zheng W, Chiu C, Correll P, Jorm L. An automated, broad-based, near real-time public health surveillance system using presentations to hospital Emergency Departments in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Public Health. 2005. 5:141.

10. van-Dijk A, Aramini J, Edge G, Moore KM. Real-time surveillance for respiratory disease outbreaks, Ontario, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009. 15:799–801.

11. Irvin CB, Nouhan PP, Rice K. Syndromic analysis of computerized emergency department patients' chief complaints: an opportunity for bioterrorism and influenza surveillance. Ann Emerg Med. 2003. 41:447–452.

12. Chapman WW, Dowling JN, Wagner MM. Classification of emergency department chief complaints into 7 syndromes: a retrospective analysis of 527,228 patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2005. 46:445–455.

13. Buehler JW, Hopkins RS, Overhage JM, Sosin DM, Tong V. CDC Working Group. Framework for evaluating public health surveillance systems for early detection of outbreaks: recommendations from the CDC Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004. 53:1–11.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download