Abstract

Background

In pulmonary infection, serum procalcitonin levels increase rapidly, probably in response to sepsis-related cytokine release from neuroendocrine cells of bronchial epithelium and inflammatory cells. We applied procalcitonin assay in critically ill patients with bacterial pneumonia.

Materials and Methods

Patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and show diffuse infiltrations in their chest X-ray were included. Quantitative bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture (≥104 CFU/mL) was performed in all cases on the 5th day of ICU admission. We excluded patients with structural lung disease, non-infectious lung infiltrations, and atypical infections such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Pneumocystis jiroveci, and viruses. Serum procalcitonin levels were measured semi-quantitatively by using PCT-Q kit.

Results

A total of 28 adult patients (M:F=23:5) were included: 11 (39.3%) medically-ill patients, 7 (25%) surgically-ill patients, and 10 (35.7%) burn patients. Serum procalcitonin level was <0.5 ng/mL in half of the cases (14/28) and ≥0.5 ng/mL in the remaining half of the cases. Compared to those with serum procalcitonin level of <0.5 ng/mL, patients with serum procalcitonin level of ≥0.5 ng/mL had more frequent mechanical ventilation, higher CRP/APACHE II scores/number of organ failure (P<0.05), and showed increased tendency for death (P=0.052). Positive bacterial BAL cultures were noted in 17 cases (60.7%). Of these, 7 cases (41.2%) showed serum procalcitonin level ≥0.5 ng/mL.

Figures and Tables

Table 2

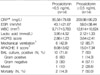

Comparison of the Characteristics according to the Application of Mechanical Ventilation (MV)

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or No. (%) unless otherwise stated.

*P value=0.023, †P value=0.000, ‡P value=0.000, §P value=0.018 ∥in hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), ¶in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), **3 in HAP and 1 in CAP

APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; mCPIS, modified clinical pulmonary infection score 14); BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MRCNS, methicilin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci

References

1. Holm A, Pedersen SS, Nexoe J, Obel N, Nielsen LP, Koldkjaer O, Pedersen C. Procalcitonin versus C-reactive protein for predicting pneumonia in adults with lower respiratory tract infection in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2007. 57:555–560.

2. Assicot M, Gendrel D, Carsin H, Raymond J, Guilbaud J, Bohuon C. High serum procalcitonin concentrations in patients with sepsis and infection. Lancet. 1993. 341:515–518.

3. Le Moullec JM, Jullienne A, Chenais J, Lasmoles F, Guliana JM, Milhaud G, Moukhtar MS. The complete sequence of human preprocalcitonin. FEBS Lett. 1984. 167:93–97.

4. Ugarte H, Silva E, Mercan D, De Mendonça A, Vincent JL. Procalcitonin used as a marker of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1999. 27:498–504.

5. Müller B, Becker KL, Schächinger H, Rickenbacher PR, Huber PR, Zimmerli W, Ritz R. Calcitonin precursors are reliable markers of sepsis in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2000. 28:977–983.

6. de Werra I, Jaccard C, Corradin SB, Chioléro R, Yersin B, Gallati H, Assicot M, Bohuon C, Baumgartner JD, Glauser MP, Heumann D. Cytokines, nitrite/nitrate, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors, and procalcitonin concentrations: comparisons in patients with septic shock, cardiogenic shock, and bacterial pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 1997. 25:607–613.

7. Mándi Y, Farkas G, Takács T, Boda K, Lonovics J. Diagnostic relevance of procalcitonin, IL-6, and sICAM-1 in the prediction of infected necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 2000. 28:41–49.

8. Kim SI, Shim BY, You HY, Jung J, Wie SH, Kim YR, Kang MW. Clinical usefulness of procalcitonin in febrile patients; comparison with erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Korean J Infect Dis. 2000. 32:129–134.

9. Choi HJ, Kim SH, Rheu KH, Lee YH, Park JY. The clinical value of procalcitonin in diagnosis of patients with fever. Infect Chemother. 2005. 37:1–8.

10. Chastre J, Fagon JY, Bornet-Lecso M, Calvat S, Dombret MC, al Khani R, Basset F, Gibert C. Evaluation of bronchoscopic techniques for the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995. 152:231–240.

11. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI document M100-S18. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; eighteenth informational supplement. 2008. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

12. Niederman MS, Mandell LA, Anzueto A, Bass JB, Broughton WA, Campbell GD, Dean N, File T, Fine MJ, Gross PA, Martinez F, Marrie TJ, Plouffe JF, Ramirez J, Sarosi GA, Torres A, Wilson R, Yu VL. American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001. 163:1730–1754.

13. American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. 171:388–416.

14. Luna CM, Blanzaco D, Niederman MS, Matarucco W, Baredes NC, Desmery P, Palizas F, Menga G, Rios F, Apezteguia C. Resolution of ventilator-associated pneumonia: prospective evaluation of the clinical pulmonary infection score as an early clinical predictor of outcome. Crit Care Med. 2003. 31:676–682.

16. Moscovitz H, Shofer F, Mignott H, Behrman A, Kilpatrick L. Plasma cytokine determinations in emergency department patients as a predictor of bacteremia and infectious disease severity. Crit Care Med. 1994. 22:1102–1107.

17. Póvoa P, Almeida E, Moreira P, Fernandes A, Mealha R, Aragão A, Sabino H. C-reactive protein as an indicator of sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1998. 24:1052–1056.

18. Carlet J. Rapid diagnostic methods in the detection of sepsis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1999. 13:483–494.

19. Boucher BA, Hanes SD. Searching for simple outcome markers in sepsis: an effort in futility? Crit Care Med. 1999. 27:1390–1391.

20. Harbarth S, Holeckova K, Froidevaux C, Pittet D, Ricou B, Grau GE, Vadas L, Pugin J. Geneva Sepsis Network. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001. 164:396–402.

21. Karzai W, Oberhoffer M, Meier-Hellmann A, Reinhart K. Procalcitonin-a new indicator of the systemic response to severe infections. Infection. 1997. 25:329–334.

22. Oberhoffer M, Karzai W, Meier-Hellmann A, Bögel D, Fassbinder J, Reinhart K. Sensitivity and specificity of various markers of inflammation for the prediction of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1999. 27:1814–1818.

23. Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, Gencay MM, Huber PR, Tamm M, Müller B. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet. 2004. 363:600–607.

24. Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, Müller C, Miedinger D, Huber PR, Zimmerli W, Harbarth S, Tamm M, Müller B. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006. 174:84–93.

25. Baughman RP. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2003. 9:397–402.

26. Boussekey N, Leroy O, Georges H, Devos P, d'Escrivan T, Guery B. Diagnostic and prognostic values of admission procalcitonin levels in community-acquired pneumonia in an intensive care unit. Infection. 2005. 33:257–263.

27. Charles PE, Kus E, Aho S, Prin S, Doise JM, Olsson NO, Blettery B, Quenot JP. Serum procalcitonin for the early recognition of nosocomial infection in the critically ill patients: a preliminary report. BMC Infect Dis. 2009. 9:49.

28. Luyt CE, Combes A, Reynaud C, Hekimian G, Nieszkowska A, Tonnellier M, Aubry A, Trouillet JL, Bernard M, Chastre J. Usefulness of procalcitonin for the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2008. 34:1434–1440.

29. Ramirez P, Garcia MA, Ferrer M, Aznar J, Valencia M, Sahuquillo JM, Menéndez R, Asenjo MA, Torres A. Sequential measurements of procalcitonin levels in diagnosing ventilator-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2008. 31:356–362.

30. Becker KL, Nylen ES, White JC, Muller B, Snider RH Jr. Clinical review 167: Procalcitonin and the calcitonin gene family of peptides in inflammation, infection, and sepsis: a journey from calcitonin back to its precursors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004. 89:1512–1525.

31. Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Procalcitonin and pneumonia: Is it a useful marker? Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2007. 9:233–240.

32. Jensen JU, Heslet L, Jensen TH, Espersen K, Steffensen P, Tvede M. Procalcitonin increase in early identification of critically ill patients at high risk of mortality. Crit Care Med. 2006. 34:2596–2602.

33. Luyt CE, Guérin V, Combes A, Trouillet JL, Ayed SB, Bernard M, Gibert C, Chastre J. Procalcitonin kinetics as a prognostic marker of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. 171:48–53.

34. Krüger S, Ewig S, Marre R, Papassotiriou J, Richter K, von Baum H, Suttorp N, Welte T. CAPNETZ Study Group. Procalcitonin predicts patients at low risk of death from community-acquired pneumonia across all CRB-65 classes. Eur Respir J. 2008. 31:349–355.

35. Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Biomarkers in respiratory tract infections: diagnostic guides to antibiotic prescription, prognostic markers and mediators. Eur Respir J. 2007. 30:556–573.

36. Clec'h C, Fosse JP, Karoubi P, Vincent F, Chouahi I, Hamza L, Cupa M, Cohen Y. Differential diagnostic value of procalcitonin in surgical and medical patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006. 34:102–107.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download