Dear Sir :

Kim and others (1) reported the successful treatment of scrub typhus in pregnant women with a single 500 mg dose of azithromycin. We would like to describe clinical course of scrub typhus in pregnant women reported in Korean literature and to mention the dosage of azithromycin used for its treatment. A search using the keywords "scrub typhus" or "tsutsugamushi disease" on KoreaMed (http://koreamed.org) yields eight reports of scrub typhus during pregnancy. One of these was excluded from our review because of diagnostic uncertainty. Further, serological confirmation could not be obtained for two patients (case 4 and case 6 in Table 1). However, since the clinical and epidemiological features of these patients were typical of scrub typhus and could not be attributed to any other illnesses observed in the Korean population, these cases were included in our series.

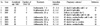

The clinical features and pregnancy outcomes of the seven cases of scrub typhus are summarized in the table. Each of the seven patients was treated with macrolides: one with erythromycin base (3.0 g/d for 3 d followed by 2.0 g/d for 4 d), one with roxithromycin (300 mg/d), and the remaining five patients with azithromycin. The time taken to achieve an afebrile state was 3 d with erythromycin and roxithromycin each and 1.4 d with azithromycin. The dosing regimen of azithromycin varied as follows: 500 mg/d followed by 250 mg/d for 6 d (case 3), 1.0 g/d followed by 500 mg/d for 2 d (case 4 and case 6), 1.0 g/d followed by 250 mg/d for 5 d (case 5), and 1.0 g/d followed by 500 mg/d for 4 d (case 7).

The doses of azithromycin used here are higher than those mentioned by Kim et al. (1, 2) primarily because these reports employed the dosing regimen used in previous reports (3, 4), which recommended a total dose of 2.0 g, i.e., 1.0 g as a loading dose followed by 0.5 g/d for 2 d. A single 500 mg dose of azithromycin is theoretically superior to the 3-day regimen with respect to convenience and safety; however, we were concerned with the possibility of inadequate treatment of scrub typhus. A study on a single dose therapy of azithromycin (2) has demonstrated adverse hepatic reactions in 5 of 47 (10.6%) patients and thrombocytopenia in 1 patient (2.1%). These rates of adverse effects appeared to be higher than those described in previous studies on azithromycin; they are generally less than 2%. On the other hand, hepatitis and thrombocytopenia are common manifestations of scrub typhus that resolve if scrub typhus is successfully treated; if not, these abnormalities continue to persist or may further aggravate. Thus, there is a possibility that a single 500 mg dose of azithromycin cures scrub typhus incompletely despite the absence of fever. The second point to be considered is that the patients included by Kim et al. (1) exhibited a short duration of illness (mean, 5 d); this is similar to the duration of illness observed in the pregnant women included in our review (5.3 d) but shorter than that in pregnant women in other countries (9.4 d) (5-8) and that in nonpregnant patients in Korea (6.0 d (2); 6.8 and 9.6 d (4)). In scrub typhus, the longer the duration of illness, the more severe the illness and the higher the complication rates. Thus, the patients in the study by Kim et al. (1) represented a subset of mild scrub typhus that responds more easily to antibiotics. The application of the results from this study to other regions where the duration of fever is longer than 7 days or the complication rates are high may be misleading. Lastly, for a clinician, it is not easy to discontinue the administration of azithromycin in the presence of fever, despite considering its long duration of action. In a previous study (2), approximately 35% of the patients were still febrile after 24 h, 15% after 48 h, and less than 10% after 72 h. If cases of potential treatment failure or recurrence are included in these febrile cases, the discontinuation of azithromycin before defervescence may prolong the illness and result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes.

Until further experience proves the efficacy of a single 500 mg dose of azithromycin for the treatment of scrub typhus, the conventional dosing regimen for the management of bacterial respiratory tract infections - 500 mg/d for 3 d - may be a more reasonable choice. Further, the necessity of a loading dose of azithromycin needs to be evaluated. The serum level of azithromycin is relatively low despite high intracellular concentration. Orienta tsutsugamushi characteristically localizes in intracellular spaces; however, these organisms are also present in the blood. This situation is similar to typhoid fever; further, the treatment failure of azithromycin in typhoid fever is attributed to its low concentrations in the blood (9). The serum levels of azithromycin are higher when it is administered as a once daily dose rather than in divided doses over 3 to 5 d. Thus, a regimen that includes a loading dose of azithromycin is theoretically more plausible for the treatment of scrub typhus.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Kim YS, Lee HJ, Chang M, Son SK, Rhee YE, Shim SK. Scrub typhus during pregnancy and its treatment: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006. 75:955–959.

2. Kim YS, Yun HJ, Shim SK, Koo SH, Kim SY, Kim S. A comparative trial of a single dose of azithromycin versus doxycycline for the treatment of mild scrub typhus. Clin Infect Dis. 2004. 39:1329–1335.

3. Choi EK, Pai H. Azithromycin therapy for scrub typhus during pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 1999. 27:1538–1539.

4. Chung MH, Han SW, Choi MG, Chang WH, Pai HJ, Shin HS, Jung HJ, Kang MH, Jung JY. Comparison of a 3-day course of azithromycin with doxycycline for the treatment of scrub typhus. Korean J Infect Dis. 2000. 32:433–438.

5. Tsui MS, Fang RC, Su YM, Li YT, Lin HM, Sun LS, Tu FC. Scrub typhus and pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1992. 49:61–63.

6. Watt G, Kantipong P, Jongsakul K, Watcharapichat P, Phulsuksombati D. Azithromycin activities against Orientia tsutsugamushi strains isolated in cases of scrub typhus in Northern Thailand. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999. 43:2817–2818.

7. Mathai E, Rolain JM, Verghese L, Mathai M, Jasper P, Verghese G, Raoult D. Case reports: scrub typhus during pregnancy in India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003. 97:570–572.

8. Phupong V, Srettakraikul K. Scrub typhus during pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature. Southeast Asian J Trop Med P ublic Health. 2004. 35:358–360.

9. Wallace MR, Yousif AA, Habib NF, Tribble DR. Azithromycin and typhoid. Lancet. 1994. 343:1497–1498.

10. Chang H, Chung MH, Kang YS, Lee HM. Scrub typhus during pregnancy. Korean J Infect Dis. 1996. 28:453–455.

11. Kim BC, Kim JH, Park CS, Han SG, Kang HA, Lee KN. A case of tsutsugamushi disease in pregnant woman. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1999. 42:1827–1830.

12. Bang JH, Choe YJ, Joh YH, Kim US, Shin JW, Kim HR, Oh MD, Kim IS, Choe KW. Scrub typhus in a pregnant woman: no evidence of intrauterine infection. Korean J Infect Dis. 2001. 33:453–455.

13. Kim KS, Choi JW, Seo HJ, Kim KH, Park SH, Seo KS, Ko SM. A case of azithromycin therapy for tsutsugamushi disease during pregnancy. Korean J Infect Dis. 2001. 33:380–382.

14. Kim YO, Kim YS, Yoon SA, Lee SS, Park TC, Lee JW. Tsutsugamushi disease in pregnant woman. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 46:2556–2559.

15. Park MC, Kim JE, Ho SE, Park IW, Park JW. Tsutsugamushi disease in a pregnant woman. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 47:2025–2028.

16. Park JY, Lee KH, Park MY, Han KW, Yang JO, Lee EY, Hong SY. A case of successfully treated scrub typhus with azithromycin in pregnant woman. Korean J Med. 2005. 68:708–711.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download