Abstract

To evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of needle aspiration biopsy of seminiferous tubules (NABST) and to represent the redistributed diagnostic results corresponding to testicular volumes and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels. In this retrospective study, we investigated 65 infertile men with either azoospermia or oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. Following NABST, specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and classified into five histological types. With pre-procedure FSH levels and testicular volumes, we evaluated the probabilities of detecting sperms within biopsy specimens. NABST led to the classification of normal spermatogenesis in 31 cases (47.7%), hypospermatogenesis in 23 cases (35.4%), maturation arrest in 4 cases (6.2%), and Sertoli cell only syndrome in 4 cases (6.2%). The success rate of reaching a histological diagnosis using NABST was 95.4% (62 out of 65 cases). Fourteen patients (21.5%) had a testicular volume <15 cc; of these, 8 patients (57.1%) had normal spermatogenesis, 2 patients (14.3%) had hypospermatogenesis, 2 patients (14.3%) had maturation arrest and 2 patients (14.3%) had Sertoli cell-only syndrome (SCO). Twelve patients (18.5%) had an FSH level ≥10 IU; of these, 6 (50%) had normal spermatogenesis, 2 patients (16.7%) had maturation arrest and 4 patients (33.3%) had SCO. Cases with an FSH level <10 IU were positively associated with a probability of detecting sperm using NABST (p<0.001). NABST is a reliable tool for the histological diagnosis of azoospermic and oligoasthenoteratozoospermic patients. The diagnostic success rate was high and associated with pathological accuracy. NABST is a convenient procedure with few complications.

While fine-needle-aspiration of human organs, as developed by Zajiceck,1 is an accepted modality of diagnosis, Orbant and Persson2 and Persson et al.3 were the pioneers of fine needle aspiration testicular biopsy for infertile males. Testicular biopsy has become one of the most basic and valuable tools in the male infertility field. The open testicular biopsy technique is routinely practiced at local urological clinics in Korea for the histological diagnosis of azoospermia and oligoasthenoteratozoospermia (OATS). However, this procedure requires surgical equipment, surgical experience,4 and is an inconvenient and invasive technique. Despite these issues, this procedure is commonly used to determine whether azoospermia is the result of ductal obstruction, non-obstruction, or testicular pathology, and can also be used in certain patients with severe OATS.56

Although needle aspiration biopsy of the seminiferous tubules (NABST) has been increasingly addressed as a diagnostic tool, there is still no consensus with regards to its histological diagnostic efficacy. Furthermore, the minimal standards for an adequate number of studies have yet to be reported in Korea. Consequently, NABST has yet to become a routine clinical method in Korea. This is unfortunate, because NABST is a simple, quick, and accurate method with few reported complications.

The present study was designed as part of our post-NABST audit to investigate the histological diagnostic outcome of NABST at a single institution, and to represent the redistributed diagnostic results corresponding to testicular volumes and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels.

This was a retrospective study consisting of 65 patients undergoing NABST in the Bundang CHA Hospital between January 2012 and December 2013. Of the 65 NABST cases, 62 were diagnosed with azoospermia, and 3 were diagnosed with severe OATS. The mean patient age was 38.4±7.0 years (Range: 31 to 45 years). The chi-square test was used to describe associations with the probability of detecting sperm in NABST specimens.

All patients underwent pre-procedure routine infertility evaluation including FSH levels (mean FSH: 8.3±4.7 IU) and testicular volumes (mean testicular volume: 16.0±4.0 cc). FSH levels were determined by a chemiluminescent immunoassay while Prader-orchiodometry was used to measure testicular volumes. Patients were excluded if testicular volume was <5 cc.

NABST was performed using a 23-gauge butterfly needle and aspirated with a 50 mL syringe unilaterally. After disinfecting the skin using iodine solution and applying local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine, the needle was inserted into the testis. The needle was moved gently back and forth repeatedly and then withdrawn and negative pressure was created using a syringe to maintain suction. For the best results, we tried at least three punctures in each testis. Following aspiration, specimens were immediately fixed in Bouin's solution, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4 µm sections. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin in the conventional way. A wide range of histological reporting systems have been described; here, we used the Johnsen score in which sperm maturation is divided into 10 different grades according to the most advanced germ cell in the tubule.7

Previously, several classification systems have been described for the histology of spermatogenesis.89101112 These systems are based upon five main histological patterns of spermatogenesis: a) normal spermatogenesis; b) hypospermatogenesis [all germ cell stages present including spermatozoa, although the number of germ cells is distinctly reduced]; c) spermatogenic arrest [incomplete spermatogenesis, failure to proceed beyond the spermatocyte stage]; d) Sertoli cell-only syndrome (SCO) [no germ cells within the seminiferous tubules[; and e) tubular sclerosis [total absence of seminiferous tubules]. We arranged the histological diagnosis categories from category a) to e).

In addition, we compared our histological diagnostic outcomes from NABST with other institutional data from 1993, and evaluated the probability of detecting sperm in NABST specimens using the chi-square test for descriptions.

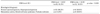

Of the 65 patients undergoing NABST, 31 patients (47.7%) were classified histologically as having normal spermatogenesis. The characteristics of the 65 patients who underwent NBST were described in Table 1. Hypospermatogenesis was diagnosed in 23 patients (35.4%), spermatogenic maturation arrest in 4 patients (6.2%), and SCO in 4 patients (6.2%). Tubular sclerosis was not detected in any of our patients. In 3 cases, we were unable to extract seminiferous tubules for diagnosis; these patients therefore received open testicular biopsy instead. Our success rate for histological diagnosis following NABST was 95.4% (62 out of 65 cases); a previous institutional publication, from Shaare Zedek hospital, reported a success rate of 91.4% (32 out of 35 cases).13 Our success rate was therefore comparable to that other institutions. It was interesting that both our own study, and the previous institutional study, reported three failed cases (Tables 2, 3).

Histologically diagnosed patients were classified according to their testicular volumes and FSH levels. Of the 65 patients, 14 (21.5%) had a testicular volume <15 cc; of these, 8 patients (57.1%) had normal spermatogenesis, 2 patients (14.3%) had hypospermatogenesis, 2 patients (14.3%) had maturation arrest and 2 patients (14.3%) had SCO. Testicular volume was ≥15 cc in 51 patients (78.5%); of these 25 patients (49.0%) had normal spermatogenesis, 22 patients (43.1%) had hypospermatogenesis, 2 patients (3.9%) had maturation arrest and 2 patients (3.9%) had SCO. The FSH level was <10 IU in 53 patients (81.5%); of these, 28 patients (52.8%) had normal spermatogenesis, 23 patients (43.4%) had hypospermatogenesis, and 2 patients (3.8%) had maturation arrest. Twelve patients (18.5%) had an FSH level ≥10 IU; of these, 6 (50.0%) had normal spermatogenesis, 2 patients (16.7%) had maturation arrest and 4 patients (33.3%) had SCO.

Overall, 71.4% (10/14) of specimens contained sperm when the testicular volume was <15 cc and 92.2% (47/51) when the testicular volume was ≥15 cc (Table 4). On the other hand, 96.2% (51/53) of specimens contained sperm when FSH was <10 IU and 50.0% (6/12) when FSH level was ≥10 IU (Table 5). We also used the chi-square test to investigate the probabilities of finding sperm in specimens according to FSH levels and testicular volumes; the only significant association was with the FSH level (p<0.001). Testicular volume (≥15 cc) was not related to the probability of finding sperm (p=0.224; Tables 4, 5).

All 3 patients with severe OATS showed a normal testicular volume and normal FSH levels. NSBST showed normal spermatogenesis in 2 of these patients and hypospermatogenesis in the other patient. There were no complications except skin bruising in some patients.

Over the last few decades, open testicular biopsy has been the preferred method for the investigation of testicular histology.14 Although NABST is recognized as a reliable and informative procedure,1516 it has not been widely used in the United States to diagnose male infertility. Recently however, NABST has been gaining increasing popularity for the diagnosis and treatment of male infertility. Because of its cellularity and easy accessibility, it is easy to perform needle aspiration in the testis. In line with the current trend towards the adoption of minimally-invasive and cost-effective approaches, NABST is clearly advantageous over the open technique.17 Therefore, there has been a increase in the usage of NABST as an important, minimally-invasive tool for the diagnosis and treatment of male infertility.18 Although NABST allows us to investigate the seminiferous tubules, its capability for investigating the interstitium is limited.1920 The open procedure is better placed for detecting in situ neoplasia or cancer, and for the overall assessment of seminiferous tubules and the interstitium.

In our study, all of the histologically prepared specimens were classified for practical, clinical use under the following groupings: normal spermatogenesis, hypospermatogenesis, maturation arrest, SCO and tubular sclerosis. In 62 out of 65 NABST patients, we were able to acquire sufficient material and provide a diagnosis by NABST. Regarding the distribution of each group, the proportion of specimens with normal spermatogenesis was similar to that reported in a previous study involving Israeli patients with azoospermia and oligospermia.12 In our current study, hypospermatogenesis was observed in 35.4% of our study population; in the Israeli study, however, there were no cases of hypospermatogenesis but many more severe cases, such as maturation arrest and SCO. In this respect, we can assume that there were ethnic differences between the infertile patients involved in these two studies. It is also possible that the indication for NABST may differ between Israelis and Koreans.

The success rate for our NABST procedure (95.4%) was comparable to that reported in previous studies (91.4%).12 In our present study, we failed to aspirate a testicular specimen in only 3 cases (4.6%). One reason for this, may have been that there was pre-existing, severe fibrotic inflammations in these three cases. In such cases, it is possible to repeat the NABST, although we did not do so in our three cases. Instead, we chose to use the open technique for these patients.

In our experience, NABST is non-invasive, reports high diagnostic rates, and has the advantage of conversion to open biopsy whenever necessary. In addition, NABST is inexpensive when compared to open biopsy and is also excellent in terms of allowing the patient to return to daily life in a rapid manner. Therefore NABST represents a very useful first line diagnostic tool for male infertility.

NABST has some limitations when we consider the entire range of testicular diseases. In normal spermatogenesis and hypospermatogenesis cases, NABST was successfully performed without complications. However, in some non-obstructive cases, appropriate amounts of sperm for artificial reproductive technology could not be acquired. Furthermore, NABST only provides pathological information on the specific area that is aspirated. NABST does not provide data relating to cancer because it cannot acquire material from the interstitial or Leydig cells which fill the space between the seminiferous tubules. For these reasons, testicular biopsy currently plays a limited role in the diagnosis of urological disease. This study was also retrospective in nature with a relatively small number of patients. Furthermore, because we did not perform the open testicular biopsy for all patients, it was not possible to compare pathological results between NABST and open testicular biopsy.

In conclusions, NABST is a reliable tool for histological diagnosis in azoospermic and oligoasthenoteratozoospermic patients. The diagnostic success rate was high and the technique provided accurate pathological information. Furthermore, NABST is a convenient procedure with few complications and could be a better diagnostic method for male infertility as an out-patient based procedure.

Figures and Tables

TABLE 1

Characteristics of the 65 couples who underwent needle aspiration biopsy of seminiferous tubules (NBST)

TABLE 2

The needle aspiration biopsy of seminiferous tubules (NBST) histological diagnostic result compared with Shaare Zedek hospital result in 199312

TABLE 3

The result of open testicular biopsy after failed needle aspiration biopsy of seminiferous tubules (NBST)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (IPET) through the High Value-added Food Technology Development Program funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA), Republic of Korea (Grant No. 314042-3).

References

1. Zajicek J. Aspiration biopsy cytology. Part 2: cytology of infradiaphragmatic Organs. In : Vielh P, editor. Monographs in Clinical Cytology. New York: Karger;1979. p. 104–109.

2. Obrant KO, Persson PS. Cytological study of the testis by aspiration biopsy in the evaluation of fertility. Urol Int. 1965; 20:176–189.

3. Persson PS, Ahrén C, Obrant KO. Aspiration biopsy smear of testis in azoospermia. Cytological versus histological examination. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1971; 5:22–26.

4. Carpi A, Agarwal A, Sabanegh E, Todeschini G, Balercia G. Percutaneous biopsy of the testicle: a mini review with a proposal flow chart for non-obstructive azoospermia. Ann Med. 2011; 43:83–89.

5. Spark RF. The infertile male: the clinicians's guide to diagnosis and treatment. New York: Plenum Medical Book Co.;1988. p. 1–365.

6. Rammou-Kinia R, Anagnostopoulou I, Tassiopoulos F, Lykourinas M. Fine needle aspiration of the testis. Correlation between cytology and histology. Acta Cytol. 1999; 43:991–998.

7. Johnsen SG. Testicular biopsy score count--a method for registration of spermatogenesis in human testes: normal values and results in 335 hypogonadal males. Hormones. 1970; 1:2–25.

8. DeKretser DM, Holstein AF. Testicular biopsy and abnormal germ cells. In : Hafez ESE, editor. Human Semen and Fertility Regulation in Men. St.Louis: Mosby;1976. p. 332–343.

9. Holstein AF, Schulze W, Davidoff M. Understanding spermatogenesis is a prerequisite for treatment. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003; 1:107.

10. Silber SJ, Nagy Z, Devroey P, Tournaye H, Van Steirteghem AC. Distribution of spermatogenesis in the testicles of azoospermic men: the presence or absence of spermatids in the testes of men with germinal failure. Hum Reprod. 1997; 12:2422–2428.

11. Nistal M, Paniagua R. Testicular biopsy. Contemporary interpretation. Urol Clin North Am. 1999; 26:555–593. vi

12. Gottschalk-Sabag S, Glick T, Bar-On E, Weiss DB. Testicular fine needle aspiration as a diagnostic method. Fertil Steril. 1993; 59:1129–1131.

13. Hendricks FB, Lambird PA, Murph GP. Percutaneous needle biopsy of the testis. Fertil Steril. 1969; 20:478–481.

14. Gottschalk-Sabag S, Glick T, Weiss DB. Fine needle aspiration of the testis and correlation with testicular open biopsy. Acta Cytol. 1993; 37:67–72.

15. Mallidis C, Baker HW. Fine needle tissue aspiration biopsy of the testis. Fertil Steril. 1994; 61:367–375.

16. Friedler S, Raziel A, Strassburger D, Soffer Y, Komarovsky D, Ron-El R. Testicular sperm retrieval by percutaneous fine needle sperm aspiration compared with testicular sperm extraction by open biopsy in men with non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 1997; 12:1488–1493.

17. Hauser R, Yogev L, Paz G, Yavetz H, Azem F, Lessing JB, et al. Comparison of efficacy of two techniques for testicular sperm retrieval in nonobstructive azoospermia: multifocal testicular sperm extraction versus multifocal testicular sperm aspiration. J Androl. 2006; 27:28–33.

18. Levin HS. Testicular biopsy in the study of male infertility: its current usefulness, histologic techniques, and prospects for the future. Hum Pathol. 1979; 10:569–584.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download