Abstract

To determine an optimal invasive intervention for renal colic patients during pregnancy after conservative treatments have been found to be unhelpful. Among the available invasive interventions, we investigated the reliability of a ureteral stent insertion, which is considered the least invasive intervention during pregnancy. Between June 2006 and February 2015, a total of 826 pregnant patients came to the emergency room or urology outpatient department, and 39 of these patients had renal colic. The mean patient age was 30.49 years. In this retrospective cohort study, the charts of the patients were reviewed to collect data that included age, symptoms, the lateralities and locations of urolithiasis, trimester, pain following treatment and pregnancy complications. Based on ultrasonography diagnoses, 13 patients had urolithiasis, and 13 patients had hydronephrosis without definite echogenicity of the ureteral calculi. Conservative treatments were successful in 25 patients. Among these treatments, antibiotics were used in 15 patients, and the remaining patients received only hydration and analgesics without antibiotics. Several urological interventions were required in 14 patients. The most common intervention was ureteral stent insertion, which was performed in 13 patients to treat hydronephrosis or urolithiasis. The patients' pain was relieved following these interventions. Only one patient received percutaneous nephrostomy due to pyonephrosis. No pregnancy complications were noted. Ureteral stent insertion is regarded as a reliable and stable first-line urological intervention for pregnant patients with renal colic following conservative treatments. Ureteral stent insertion has been found to be equally effective and safe as percutaneous nephrostomy, which is associated with complications that include bleeding and dislocation, and the inconvenience of using external drainage system.

Unlike the abdominal discomfort that is frequently observed during pregnancy, renal colic while often infrequent during pregnancy is potentially dangerous because it can lead to hospitalization and adverse effects for both the mother and the fetus.1

One of the main causes of renal colic is urolithiasis.23 The incidence of symptomatic urolithiasis during pregnancy varies widely from 1/200 to 1/2,000 women, and this incidence is not different from the incidence that has been reported in the non-pregnant female population of reproductive age.4 The occurrence of a urolithiasis during pregnancy is a risk to both the mother and fetus and may be a contributing factor in premature birth.56

Furthermore, normal anatomic changes within the urinary tract of the pregnant patient may not only predispose the patient to urolithiasis formation but may also pose a diagnostic challenge. Physiologic hydronephrosis can occur in 90% of right kidneys and up to 67% of left kidneys during pregnancy.7 The predominance of right upper tract dilation compared to that of the left may be caused by a combination of various factors that include the preferential compression of the right ureter due to uterine dextrorotation and the protection of the left ureter by the gas-filled sigmoid colon.8

Regarding the treatment of renal colic during pregnancy, conservative management results in spontaneous calculi passage in approximately 70–80% of pregnant women.910 In cases in which invasive interventions are required, ureteral stent insertion and percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) are preferred and less invasive interventions. Ureteroscopic stone removal is also occasionally performed.

In this study, the reliability and stability of ureteral stent insertions in pregnant patients with renal colic following unsuccessful conservative treatments were analyzed.

Between June 2006 and February 2015, a total of 826 pregnant patients came to emergency room and urology outpatient department. Of these patients, 39 patients had renal colic. In this retrospective cohort study, the charts of the patients were reviewed to collect data that included age, symptoms, the laterality of renal colic, sizes and locations of urolithiasis, trimester of diagnosis, pain after treatment and pregnancy complications. The pregnancy complications included preterm labor, preterm premature membrane rupture, and pre-eclampsia.

The diagnoses of urolithiasis in the pregnant women were based on the clinical presentation, the presence of microscopic hematuria on urinalysis and transabdominal ultrasonography.

Cases with demonstrable hydronephrosis and no evidence of calculi were classified as having renal colic attributable to physiological hydronephrosis consistent with pregnancy. Microscopic hematuria was defined as >5 red blood cells/high power field (RBCs/HPF), and pyuria was diagnosed when >5 white blood cells/high power field (WBCs/HPF) were observed.

Conservative management included observation with hydration or analgesics and antibiotics when bacterial infections were present.

The urological interventions included ureteral stent insertion, PCN, and ureteroscopic stone removal and were considered when renal colic resistant to pharmacological treatment, sepsis, or obstruction of a solitary kidney were present. The follow-up information included the outcome for the infant and the additional procedures that were required after the initial procedures.

Research involving human subjects that is reported in the manuscript must have been performed with the approval of an appropriate ethics committee in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Moreover, written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all participants.

Of the total thirty-nine patients with renal colic, twenty-seven patients (74.4%) were in the second trimester, four (10.2%) were in the first trimester, and eight patients (20.4%) were in the third trimester.

The mean patient age at presentation was 30.49±3.24 years.

Twenty-five renal colic patients (64.1%) had right-sided colic, and fourteen patients (35.9%) had left-sided colic.

The clinical features included gross hematuria in six patients (15.4%), fever in five patients (12.8%), and increased urinary frequency in one patient (2.56%).

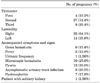

The laboratory tests revealed microscopic hematuria in ten patients (25.6%) and pyuria in twelve patients (30.8%). Asymptomatic urinary tract infections were found in eight patients (20.5%), and pyelonephritis was observed in seven patients (17.9%). One patient (2.56%) had only one kidney (Table 1).

Based on ultrasonography results, thirteen patients (33.3%) were diagnosed with urolithiasis, and thirteen patients (33.3%) were diagnosed with hydronephrosis without definite echogenicity of ureteral calculi using ultrasonography.

Among the patients with urolithiasis, the sizes of the calculi varied from 2 mm to 10 mm (mean: 5.2 mm). Regarding their locations, distal ureteral calculi were observed in seven patients, proximal ureteral calculi were found in six patients, and nephrolithiases were observed in three patients. One patient had proximal ureteral and renal calculi, and another single patient had proximal ureteral, distal ureteral and renal calculi (Fig. 1).

Management was initially conservative for all patients. Twenty-five patients (64.1%) were successfully treated with conservative management. Conservative management included hydration, and analgesics and antibiotics to treat bacterial infections. Among these management strategies, antibiotics were used in fifteen patients (38.5%), and the remaining patients received only hydration and analgesics.

Another fourteen patients (35.9%) required urological interventions due to persistent pain, prolonged infection, hydronephrosis, and urolithiasis. The most common intervention was ureteral stent insertion, which was performed in thirteen patients (33.3%) to treat hydronephrosis or urolithiasis. All of the patients' pain was relieved following the interventions. Only one patient (2.56%) underwent PCN due to pyonephrosis (Table 2).

We divided renal colic patients by gestational trimesters at presentation. The diagnosis was four patients (10.3%) in the first trimester, twenty-seven patients (69.2%) in the second trimester, and eight patients (20.5%) in the third trimester. All the renal colic patients in the first trimester were successfully managed with conservative management. Among the twenty-seven patients in the second trimester, eighteen patients were successfully treated with conservative management. Ureteral stent insertion was perfomed in eight patients and the remaining patient was managed by PCN. Of the eight patients in the third trimester, three patients were completely relieved with conservative management and five patients were treated by ureteral stent insertion (Table 3).

None of the patients underwent ureteroscopic stone removal or open surgery. No pregnancy complication was noted in any of the patients, and all of the fetuses were delivered without complications.

The diagnosis of renal colic in pregnancy is based on clinical symptoms and findings from radiographic imaging modalities. The use of imaging to investigate conditions such as urolithiasis or hydronephrosis in pregnant women remains controversial due to the potential teratogenic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic risks to the fetuses. Computed tomography exposes the fetus a momentous radiation dose. Single-shot intravenous pyelography involves the acquisition of a single radiograph 30 minutes after the introduction of contrast medium and is considered to be confirmatory in up to 96% of patients.11 A series of intravenous urography procedures delivers the fetus to a mean radiation dose of 1.7 mGy and a maximal dose of 10 mGy. In contrary, a single X-ray exposes the fetus to a mean radiation dose of 1.4 mGy and a maximal dose of 4.2 mGy.2 Therefore, before deciding to choose a suitable imaging modality, pregnant women should be provided with detailed cautions about the teratogenic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic risks to the fetuses which are associated with each imaging technique.

Transabdominal ultrasonography is considered to be the imaging method of choice for routine evaluations of renal colic in pregnant women because it has no risk of radiation exposure. Moreover, in the diagnosis of urolithiasis, transabdominal ultrasonography has an appropriate sensitivity and specificity of 34% and 86%.121314

The management of renal colic during pregnancy is principally conservative. Approximately 70–80% of women with symptomatic hydronephrosis or urolithiasis during pregnancy are sufficiently treated with hydration, analgesics and antibiotics. Additional further medical treatments are needed in 20–30% of women. Those therapeutic procedures are epidural block for pain relief and the use of beta-adrenoreceptor blockers.5 Beta-adrenoreceptor blockers are thought to stimulate the contractility of the renal pelvis and ureter and thus increase the urine flow rate and assist in the spontaneous expulsion of urolithiasis.6

The indications for invasive treatment are the severe pain which is resistant to pharmacological treatment, sepsis, and obstruction in a solitary kidney. In pregnant women, ureteral stent insertion and PCN have been used to treat renal colic because these techniques are minimally invasive and are used as the gold standard for the surgical treatment of renal colic in pregnancy. These techniques also have the advantage that they can be performed under local anesthesia. The goal of treatment is to relieve the obstruction and prevent further regression in renal function. PCN is very effective, but is associated with complications that include bleeding and the inconvenience of draining externally.

In pregnancy, ureteral stent insertion can be performed through ureteroscopy and the location of the ureteral stent could be confirmed by ultrasonography. Ureteral stent insertion is as effective as PCN and considered to be a safe and effective first-line intervention for later stage pregnant patients with hydronephrosis or urolithiasis.15 Both ureteral stent and PCN therapies should be exchanged periodically to avoid incrustation.

Additionally, ureteroscopic stone removal during pregnancy is a safe procedure that can be performed with a rigid, semi-rigid, or flexible instrument.16 Ureteroscopic stone removal, on the other hand, typically requires general anesthesia and has the possibility of ureteral perforation and sepsis. Ureteroscopic stone removal should be avoided during the third trimester due to the anatomical changes in the bladder that are secondary to compression by the gravid uterus.17 Johnson et al.18 and Lifshitz and Lingeman19 found no statistically significant risk factors for the development of an obstetric complication following ureteroscopic stone removal during pregnancy.

During pregnancy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) is not advised, nonetheless there have been two case reports which informed successful PCNLs in early pregnancy.2021 Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy is contraindicated in pregnant patients due to the effects of the shockwave on the fetus, which can cause a miscarriage.22

In this study, we mainly considered which surgical intervention could avoid the most side effects when pain is not resolved by conservative management. Although both ureteral stent insertion and PCN were known as safe interventions, we performed ureteral stent insertion mainly to avoid bleeding and the inconvenience of using external drainage. Thirteen patients were treated by ureteral stent insertion and their treatments were successful. There were no pregnancy complications and all of the fetuses were delivered without any complications. Consequently, this study could suggest ureteral stent insertion as the most effective and safe treatment in renal colic during pregnancy without leading to complications.

Further prospective studies with a follow-up are needed to compare the distinctions between ureteral stent insertion and PCN.

Ureteral stent insertion is considered to be a reliable and stable first-line urological intervention for pregnant patients with renal colic following the failure of conservative treatment. Ureteral stent insertion is equally effective and safe with PCN which is associated with complications that include bleeding and the inconvenience of using an external drainage system. Therefore, ureteral stent insertion is considered to be a first-line intervention for pregnant renal colic patients when pain is not resolved by conservative management.

Figures and Tables

| FIG. 1Diagnosis by transabdominal ultrasonography during pregnancy. (A) Two kidney stones, (B) A proximal ureteral calculus at the ureteropelvic junction, (C) A distal ureteral calculus at the ureterovesical junction, (D) Hydronephrosis without definite echogenicity of ureteral calculi in ultrasonography. |

References

1. Andreoiu M, MacMahon R. Renal colic in pregnancy: lithiasis or physiological hydronephrosis? Urology. 2009; 74:757–761.

2. Srirangam SJ, Hickerton B, Van Cleynenbreugel B. Management of urinary calculi in pregnancy: a review. J Endourol. 2008; 22:867–875.

3. Wayment RO, Schwartz BF. Pregnancy and Urolithiasis [Internet]. USA: Emedicine;c2009. Updated 2015 Apr 17. Cited 2014 Nov 19. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/455830-overview/.

4. Gorton E, Whitfield HN. Renal calculi in pregnancy. Br J Urol. 1997; 80:Suppl 1. 4–9.

6. Charalambous S, Fotas A, Rizk DE. Urolithiasis in pregnancy. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009; 20:1133–1136.

7. Peake SL, Roxburgh HB, Langlois SL. Ultrasonic assessment of hydronephrosis of pregnancy. Radiology. 1983; 146:167–170.

9. Hendricks SK, Ross SO, Krieger JN. An algorithm for diagnosis and therapy of management and complications of urolithiasis during pregnancy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991; 172:49–54.

10. Juan YS, Wu WJ, Chuang SM, Wang CJ, Shen JT, Long CY, et al. Management of symptomatic urolithiasis during pregnancy. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2007; 23:241–246.

11. Butler EL, Cox SM, Eberts EG, Cunningham FG. Symptomatic nephrolithiasis complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 96:753–756.

12. Patel SJ, Reede DL, Katz DS, Subramaniam R, Amorosa JK. Imaging the pregnant patient for nonobstetric conditions: algorithms and radiation dose considerations. Radiographics. 2007; 27:1705–1722.

13. Swanson SK, Heilman RL, Eversman WG. Urinary tract stones in pregnancy. Surg Clin North Am. 1995; 75:123–142.

14. Dhar M, Denstedt JD. Imaging in diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of stone patients. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009; 16:39–47.

15. Evans HJ, Wollin TA. The management of urinary calculi in pregnancy. Curr Opin Urol. 2001; 11:379–384.

16. Scarpa RM, De Lisa A, Usai E. Diagnosis and treatment of ureteral calculi during pregnancy with rigid ureteroscopes. J Urol. 1996; 155:875–877.

17. Travassos M, Amselem I, Filho NS, Miguel M, Sakai A, Consolmagno H, et al. Ureteroscopy in pregnant women for ureteral stone. J Endourol. 2009; 23:405–407.

18. Johnson EB, Krambeck AE, White WM, Hyams E, Beddies J, Marien T, et al. Obstetric complications of ureteroscopy during pregnancy. J Urol. 2012; 188:151–154.

19. Lifshitz DA, Lingeman JE. Ureteroscopy as a first-line intervention for ureteral calculi in pregnancy. J Endourol. 2002; 16:19–22.

20. Shah A, Chandak P, Tiptaft R, Glass J, Dasgupta P. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in early pregnancy. Int J Clin Pract. 2004; 58:809–810.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download