Abstract

Successful tuberculosis control depends on good adherence to treatment. Yet, limited data are available on the efficacy of methods for improving the adherence of patients of low socioeconomic status. We evaluated the impact of physician-provided patient education on adherence to anti-tuberculosis medication in a low socioeconomic status and resource-limited setting. A pre-/post-intervention study was conducted at a suburban primary health care clinic in Bangladesh where an intensive education strategy was established in May 2006. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients from March 2005 to April 2006 (pre-intervention) and from May 2006 to December 2007 (post-intervention) were compared. Among 354 patients, 198 (56%) were treated before intervention and 156 (44%) were treated after intervention. Cumulative adherence to anti-tuberculosis medication was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group in univariate and multivariate analyses. Physician's education can contribute to increasing the adherence of patients in resource-limited settings.

The public-private mix (PPM) approach is an effective way to improve detection rates of the directly observed treatment, short course (DOTS) approach with comparative treatment success rate in tuberculosis.1,2 However, the PPM approach has a lower rate of success than expected in some situations.3 For the PPM strategy to be successful, it is important to find ways to improve the adherence of patients in clinics, especially those patients of low socioeconomic status (SES). However, few studies have investigated the impact of education on adherence, and existing findings are inconsistent.4-7 We evaluated the impact of physician-provided education on adherence to treatment in patients of low SES in a primary health care clinic.

The current study was designed as a pre-/post-intervention study. The control group consisted of tuberculosis patients treated from March 2005 to April 2006, and the intervention group consisted of patients treated from May 2006 to December 2007 at Bangladesh-Korea Friendship Hospital. The facility is a primary health care clinic located in Savar, a suburban industrial complex area adjacent to Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. We followed the standard short course treatment regimen recommended by the World Health Organization and used a fixed-dose formula provided free of charge by the national tuberculosis control program in Bangladesh. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Daegu Fatima Hospital (No. DFH10OT088).

From May 2006, we changed the irregular visiting schedules of the patients into regular ones as follows: every week during the initial month of treatment, every other week during the next month, and then every month until the end of treatment. We scheduled the next visit 3 days before drug exhaustion and directed each patient to bring the remaining pills at every visit. Education was performed directly by the physicians on every visit. The contents of our education included the high incidence and mortality rates of tuberculosis in Bangladesh, how to take anti-tuberculosis drugs and their major side effects, and the consequences of nonadherence and of early discontinuation of medication because of symptom relief (e.g., treatment failure, emerge of drug resistance, death). To confirm patients' full understanding, we asked the following questions: What could happen when you stop taking the medicine? What could happen if you don't take the medicine regularly? How long should you take this medicine? What are the important side effects of medication? How should you take the medicine? How many pills are left on your prescription?

Adherence was defined as patient's attendance at the scheduled visit and regular medication with over 90% of doses prescribed. The collected data were reviewed and analyzed retrospectively. Categorical and continuous variables were compared by using the Pearson chi-square test and Student's t-test, respectively, to test for homogeneity between the intervention and control groups. The Kaplan-Meier method and Cox's proportional hazards model were used to evaluate the relationship between adherence to medication and education in the two groups. Multivariate analyses were performed by using the Cox-regression hazard model in the backward stepwise conditional manner. Variables with p<0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. Statistical analyses of the data were performed with SPSS for Windows (version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

A total of 354 patients participated: 198 patients (56%) were treated in the pre-intervention period, and 156 patients (44%) were treated in the post-intervention period.

The patients' mean (±SD) age was 35 (±15) years in the pre-intervention group and 35 (±16) years in the post-intervention group (p=0.90). Mean body weight (±SD) was 42 (±9) kg in the pre-intervention group and 42 (±7) kg in the post-intervention group (p=0.46). A total of 126 (64%) patients in the pre-intervention group and 85 (55%) in the post-intervention group were male (p=0.08). Of these patients, 145 (73%) in the pre-intervention group and 118 (76%) in the post-intervention group lived within 30 minutes of the clinic by three-wheeler rickshaw (p=0.43). Two hundred seventy-two patients (77%) had pulmonary tuberculosis, and 142 (52%) of them were smear-positive for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) on sputum examination. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis was significantly more common in the control group (56/198, 28%) than in the intervention group (26/156, 17%; p=0.010). However, other characteristics did not differ significantly between the two groups (p>0.05, Table 1).

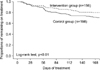

The proportion of patients who remained adherent at day 168 and the cumulative adherence to anti-tuberculosis medication was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group (Table 1, Fig. 1). The multivariate analysis included the following variables: age, male sex, AFB-negative, intervention group (p<0.10 in the univariate analysis), and tuberculosis type (which was significantly different between the intervention group and the control group). Independent risk factors for nonadherence were pre-intervention group, age, and AFB-negative in the Cox-regression multivariate analysis (p<0.05, Table 2). Subjects in the intervention group were more likely than those in the control group to continue taking medication in the multivariate Cox's proportional hazards model (Table 2). Because the prevalence of pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis differed significantly between the groups, we stratified the analyses by tuberculosis type. Cumulative adherence in the intervention group was higher than in the control group among both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis patients (Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test; chi-square 8.4 and 11.3, p<0.05 each).

Bangladesh, which ranks sixth in the world in terms of tuberculosis burden, first implemented a tuberculosis program with a DOTS strategy in 1984. Treatment success rates reached 92% in 2007.8 However, detection rates are still only 66%,8 and many tuberculosis patients are still treated in clinics.

We treated suburban tuberculosis patients in a clinic; however, treatment success rates were not satisfactory. Because of poorly available resources, to improve adherence, we provided patients with direct education from physicians.

Adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment is influenced by various factors. For example, knowledge about the disease, the duration of treatment, and schedule of follow-up are associated with adherence to anti-tuberculosis medication.9 Distance and time to health facilities, male gender (male patients are usually the breadwinners of their families), and stigma that tuberculosis is incurable are also major constraints to treatment adherence, especially in developing countries.10,11 Consistent with the previous studies, compliance was also affected by multiple factors in our study.

Previous studies have attempted to educate tuberculosis patients on better adherence. Thiam et al.6 reported that a strategy including reinforced counseling between health personnel and patients improved adherence to the anti-tuberculosis medications. However, a study conducted in Pakistan showed that intensive counseling had a limited impact on adherence.4 Morisky et al.5 also reported that there was no significant improvement in treatment adherence in the intervention group even though intensive education and a monetary incentive were provided to the patients. In our study, education was effective even though most patients were of low SES, most were poorly educated, half were completely uneducated and illiterate, and defaulter tracing was not applicable. In our opinion, the success of our intervention, in contrast with other previous studies that failed, was possibly due to the qualified health care staff and their desire to improve treatment outcomes. In a recent study, Hane et al.12 found that health care staff can play a key role in promoting adherence to treatment, which justifies the training component of the strategy tested and the need for improved counseling.

A major limitation of our study on physician-provided patient education was that defaulter tracing could not be applied. Although our intervention was effective, the treatment success rate was only 78%. Subsequent intervention using defaulter tracing and subsequent DOTS for defaulters is needed. Second, we started to educate the patients and changed the irregular visiting schedules of the patients into regular ones in a bundle of patients at the same time. For this reason, it is possible that not only the education but also the change of schedule contributed to the improved adherence of the educated patients. Third, this study was not designed as randomized controlled trial but was designed as a before and after study.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that direct education from physicians can improve the adherence of patients to tuberculosis treatment even when the patients are poorly educated and of low SES. Physician's education is also important and can contribute to increasing the adherence of patients in resource-limited settings, as can the education of other health care workers.

Figures and Tables

FIG. 1

Kaplan-Meier curve of adherence to tuberculosis medication for 354 patients with tuberculosis. The cumulative adherence to anti-tuberculosis medication was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group (log-rank test; chi-square 17.5, p<0.01).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express our gratitude to Chang-Sup Kim and Myoung-Jin Kim, chief and vice chief of the Bangladesh office of the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), for their executive support performing this project.

We express our gratitude to Sang-Won Park and Chang-Seop Lee, predecessors in the Department of Medicine of Bangladesh-Korea Friendship Hospital, for their advice and support.

References

1. Arora VK, Sarin R, Lönnroth K. Feasibility and effectiveness of a public-private mix project for improved TB control in Delhi, India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003. 7:1131–1138.

2. World Health Organization. The Stop TB Strategy: Building on and Enhancing DOTS to Meet the TB-related Millennium Development Goals. 2006. Geneva: World Health Organization.

3. Quy HT, Lönnroth K, Lan NT, Buu TN. Treatment results among tuberculosis patients treated by private lung specialists involved in a public-private mix project in Vietnam. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003. 7:1139–1146.

4. Liefooghe R, Suetens C, Meulemans H, Moran MB, De Muynck A. A randomised trial of the impact of counselling on treatment adherence of tuberculosis patients in Sialkot, Pakistan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999. 3:1073–1080.

5. Morisky DE, Malotte CK, Choi P, Davidson P, Rigler S, Sugland B, et al. A patient education program to improve adherence rates with antituberculosis drug regimens. Health Educ Q. 1990. 17:253–267.

6. Thiam S, LeFevre AM, Hane F, Ndiaye A, Ba F, Fielding KL, et al. Effectiveness of a strategy to improve adherence to tuberculosis treatment in a resource-poor setting: a cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007. 297:380–386.

7. Volmink J, Garner P. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of strategies to promote adherence to tuberculosis treatment. BMJ. 1997. 315:1403–1406.

8. World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control 2009: Epidemiology, Strategy, Financing. 2009. Geneva: World Health Organization.

9. Menzies R, Rocher I, Vissandjee B. Factors associated with compliance in treatment of tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1993. 74:32–37.

10. Hill PC, Stevens W, Hill S, Bah J, Donkor SA, Jallow A, et al. Risk factors for defaulting from tuberculosis treatment: a prospective cohort study of 301 cases in the Gambia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005. 9:1349–1354.

11. Khan MA, Walley JD, Witter SN, Imran A, Safdar N. Costs and cost-effectiveness of different DOT strategies for the treatment of tuberculosis in Pakistan. Directly observed treatment. Health Policy Plan. 2002. 17:178–186.

12. Hane F, Thiam S, Fall AS, Vidal L, Diop AH, Ndir M, et al. Identifying barriers to effective tuberculosis control in Senegal: an anthropological approach. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007. 11:539–543.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download