Abstract

Humans can be incidentally parasitized by third-stage larvae of Anisakis species following the ingestion of raw or undercooked seafood. Acute gastric anisakiasis is one of the most frequently encountered complaints in Korea. However, duodenal anisakiasis with duodenal ulcer had not been reported in Korea, despite the habit of eating raw fish. In this case, a 47-year-old man was hospitalized because of sharp epigastric pain and repeated vomiting after eating raw fish 3 days previously. On admission, esophagogastroduodenoscopic examination revealed an active duodenal bulb ulcer. At 5 mm away from the ulcer margin, a whitish linear worm was found with half of its body penetrating the duodenal mucosa. Herein, we report this case of duodenal anisakiasis accompanied by duodenal ulcer.

The disease anisakiasis was first recognized by Van Thiel in 1960.1 It is caused by an infestation of the third-stage larvae of Anisakis simplex. A. simplex is distributed worldwide and is frequently found in a large variety of fish consumed by humans. Eating uncooked fish or seafood containing the third-stage larvae causes infection. After ingestion, larvae can penetrate the host stomach or intestinal wall. Humans are only accidental hosts of this parasite. The resulting disease, known as anisakiasis or anisakidosis, is due mainly to two mechanisms: allergic reaction and direct tissue damage. The former ranges from isolated urticaria and angioedema to life-threatening anaphylactic shock associated with gastrointestinal symptoms (gastroallergic anisakiasis). Allergic reactions can occur after primary infection, solely through the presence of Anisakis allergens in food.1,2 Tissue damage is due to invasion of the gut wall and development of eosinophilic granuloma, ulcer, or perforation.2,3 Cases of gastric anisakiasis (95%) are more common than those of enteric anisakiasis, and the latter is rarely reported.4 Anisakis larvae can be seen directly by esophagogastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy and can be removed with biopsy forceps.

Only one similar report exists in which an Anisakis larva was found with a duodenal ulcer, but it was not reported in detail.3 Herein, we report a case of a 47-year-old man who had duodenal anisakiasis with a duodenal ulcer.

A 47-year-old otherwise healthy man visited our hospital with a complaint of sharp epigastric pain lasting 2 days. He also had nausea and vomiting without diarrhea. The patient did not have H. pylori and had no abnormal findings on an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) conducted 6 months previously. Additionally, he had no recent travel history and no significant medical history; however, the patient had eaten a raw flatfish 3 days before admission. The patient had normal vital signs and was afebrile. On physical examination, he had increased bowel sounds and direct tenderness in the epigastric area but did not have abdominal distention or a palpable mass. Laboratory tests revealed normal biochemical and hematologic blood indexes, except for an elevated white blood cell count of 15,500/mm3 with a normal eosinophil count and C-reactive protein level of 3.63 mg/dl.

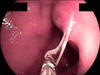

On admission, EGD revealed a round to oval active duodenal ulcer, about 10 mm in diameter, with a sharp margin and marginal elevation at the duodenal bulb. At 5 mm away from the ulcer margin, a whitish linear worm was found with half of its body penetrating the duodenal mucosa (Fig. 1). The worm was removed by using biopsy forceps (Fig. 2). Additionally, a rapid urease test showed a negative result. A proton pump inhibitor (pantoprazole 40 mg, 1 tablet qd) was administered to treat the duodenal ulcer. The patient's symptoms rapidly improved after removal of the duodenal Anisakis, and the patient was discharged on the third day after EGD.

The follow-up EGD after 4 weeks of treatment for the duodenal ulcer revealed complete healing at the ulcer site without Anisakis (Fig. 3).

Anisakiasis, which was first reported by Van Thiel in 1960,1 is caused by the third-stage larvae of Anisakis species, mainly A. simplex, and to a much lesser extent A. physeteris, after the ingestion of raw or undercooked fish or seafood. The adult Anisakis lives in the stomach of marine mammals such as whales and dolphins. Crustaceans are the first intermediate hosts. The second intermediate hosts include various species of fish and some cuttlefish. Humans are only accidental hosts.2

Anisakiasis is classified as either the luminal or the invasive form, according to the presence of bowel wall invasion by Anisakis larvae.2 The luminal form does not cause major clinical symptoms, but the invasive form can. The invasive form is subdivided into gastric and intestinal types, according to the penetration site. Cases of gastric anisakiasis (95%) are more common than are those of enteric anisakiasis, and the latter is rarely reported.2,3

Anisakiasis is caused by two main mechanisms: allergic reactions and direct tissue damage. The former ranges from isolated urticaria and angioedema to life-threatening anaphylactic shock associated with gastrointestinal symptoms. Allergic reactions can occur after the primary infection of Anisakis with exposure to allergens in the food. Direct tissue damage is due to parasite invasion of the gut wall, development of eosinophilic granuloma, or perforation.4

Sudden abdominal pain occurs within 12 to 72 hours after the ingestion of raw fish in cases of acute gastric anisakiasis. In these instances, the larvae can be seen directly by EGD and can be removed with biopsy forceps. Chronic anisakiasis of the stomach may mimic a peptic ulcer, chronic gastritis, or gastric cancer. There are occasional reports of gastric anisakiasis with a morphology that resembles the Borrmann type 2 advanced gastric cancer or a type IIa + III early gastric cancer.5 There are also a few reports of the endoscopic discovery of a worm in the base of a gastric ulcer.6 Patients with enteric anisakiasis have diffuse and colicky abdominal pain within several days after ingesting raw fish. It has been reported that anisakiasis is usually a self-limiting disease cured by conservative management for 1 to 2 weeks after the onset of symptoms.

A positive result on a serological test has been shown to be helpful when diagnosing; however, positive IgE values against Anisakis in subjects without symptoms of allergy cannot be considered a reliable indicator. This antibody has been detected in 25% of healthy controls and lacks specificity because of cross-reactivity with other parasite antigens. Additionally, it is not generally available and is therefore of limited benefit in early diagnosis.7 Increased eosinophil levels are observed in less than half of the patients with anisakiasis, and when the eosinophil levels are increased, they tend to be normal on the first hospital day and gradually rise later.4,7 This case showed a normal eosinophil level; the eosinophil count is therefore not likely to be a useful marker in diagnosing small-intestinal anisakiasis.

Intestinal anisakiasis (including duodenal anisakiasis) causes direct damage to the gut wall, whereas the role of an allergenic response in the pathogenesis is not clear. The diagnosis of intestinal involvement is still difficult, and often it is only possible with a histologic specimen. A history of raw fish ingestion within 3 days is the only specific clinical clue to the diagnosis, but it may be missed because the patient is often unaware of the risk.7 Imaging may be useful in guiding the diagnosis. Plain X-ray is not specific, whereas small-bowel X-ray series may show a localized stenosis due to focal edema.8 Sonography provides an easy, noninvasive, inexpensive alternative with high sensitivity, if guided by history and clinical suspicion. A common sonographic finding is a relatively large amount of ascitic fluid and dilatation of the small intestine and marked localized edema of Kerckring's folds.8 Serology, if specific IgE is used, could be helpful for the diagnosis. In contrast, other techniques (latex-based agglutination procedures, Ouchterlony tests, immunoelectrophoresis, immunofluorescence, indirect hemagglutination, complement fixation, immunoblotting, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) are of limited benefit in early diagnosis, because they lack specificity as a result of cross-reactivity with other parasite antigens and are generally unavailable.9 Microscopically, a definite diagnosis is confirmed by the recognition of Anisakis larvae. The lesions range from diffuse interstitial edema to phlegmonous infiltrate with numerous eosinophils and epithelioid cell granulomas with foreign body giant cells.7 In addition, capsule endoscopy recently revealed small intestine anisakiasis beyond the reach of fiber endoscopy.10

The best treatment for anisakiasis is prophylaxis. The larvae cannot survive in temperatures above 60℃ for 10 minutes or at -20℃ for 24 hours. If an EGD exam reveals that the larvae have invaded the intestine or the stomach wall, then endoscopic removal consists of grasping the body of the worm and slowly pulling it away.5

The patient in our case had duodenal anisakiasis with duodenal ulcer, which is a rarely involved site. Additionally, this patient did not have H. pylori or other factors leading to duodenal ulcer, and Anisakis did not seem to produce the duodenal ulcer. In the present case, we believe that the possible mechanisms of duodenal anisakiasis accompanied by duodenal ulcer without gastric Anisakis were increased gastric acid output, increased gastric emptying, and easily penetrable inflamed mucosa adjacent to the duodenal ulcer.

In summary, we experienced a rare case of a 47-year-old Korean male who had duodenal anisakiasis accompanied by duodenal ulcer without gastric Anisakis, which was successfully treated by endoscopic removal of Anisakis with biopsy forceps.

Figures and Tables

FIG. 1

The esophagogastroduodenoscopy at admission showed a round to oval active duodenal ulcer, about 10 mm in diameter, with sharp margins and marginal elevation at the duodenal bulb. At 5 mm away from the ulcer margin, a whitish Anisakis larva was found with half of its body penetrating the duodenal mucosa.

References

1. Van Thiel P, Kuipers FC, Roskam RT. A nematode parasitic to herring, causing acute abdominal syndromes in man. Trop Geogr Med. 1960. 12:97–113.

2. Kang DB, Oh JT, Park WC, Lee JK. Small bowel obstruction caused by acute invasive enteric anisakiasis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010. 56:192–195.

3. Lee EJ, Kim YC, Jeong HG, Lee OJ. The mucosal changes and influencing factors in upper gastrointestinal anisakiasis: analysis of 141 cases. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009. 53:90–97.

4. Choi SJ, Lee JC, Kim MJ, Hur GY, Shin SY, Park HS. The clinical characteristics of Anisakis allergy in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2009. 24:160–163.

5. Okada F, Hiratsuka H. Araki T, Tsuji M, Katsu K, Hirata I, editors. Gastric anisakiasis. Clinical parasitology for endoscopist [Japanese]. 2000. Tokyo: Igaku-tosho-shuppan;98–102.

6. Takeuchi K, Hanai H, Iida T, Suzuki S, Isobe S. A bleeding gastric ulcer on a vanishing tumor caused by anisakiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000. 52:549–551.

7. Lee CM, Choi JY, Kim JH. Intestinal obstruction caused by anisakiasis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2008. 74:154–156.

8. Matsui T, Iida M, Murakami M, Kimura Y, Fujishima M, Yao Y, et al. Intestinal anisakiasis: clinical and radiologic features. Radiology. 1985. 157:299–302.

9. Audicana MT, Ansotegui IJ, de Corres LF, Kennedy MW. Anisakis simplex: dangerous--dead and alive? Trends Parasitol. 2002. 18:20–25.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download