Abstract

Treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist is the treatment of choice for central precocious puberty (CPP). Many of the previous studies concerning the auxological effects of treatment with GnRH agonist in CPP have focused on final height. Much less attention has been paid to changes in body weight. However, concerns have been expressed that CPP may be associated with increased body mass index (BMI) both at initial presentation and during GnRH agonist treatment. We retrospectively reviewed the height and BMI of 38 girls with CPP. All patients were treated with GnRH agonist over 18 months. The height standard deviation score (SDS) for chronological age was significantly decreased during GnRH agonist treatment, whereas the height SDS for bone age was significantly increased. The predicted adult height was increased from 157.78±6.45 cm before treatment to 161.41±8.97 cm at 12 months after treatment. The BMI SDS for chronological age was significantly increased during treatment. The BMI SDS of normal-weight girls increased more than did the BMI SDS of overweight girls, but the increase was not significant. Preventive measures, such as increased physical activity, can be introduced to minimize possible alterations in body weight, and a long-term follow-up study is required to elucidate whether GnRH agonist treatment in Korean girls with CPP affects adult obesity.

Precocious puberty is defined as secondary sexual characteristics that come out more quickly than two standard deviations of the mean value; generally, precocious puberty is the onset of secondary sexual characteristics before 8 years of age in girls and 9 years in boys.1 Precocious puberty may be classified as gonadotropin-dependent, which is called central precocious puberty (CPP), and gonadotropin-independent, which is also called precocious pseudopuberty. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist treatment for CPP continuously desensitizes the gonadotropic cells of the pituitary to the stimulatory effect of endogenous GnRH and effectively postpones the progression of rapid bone maturation and sexual precocity. This process also helps to increase pubertal duration, postpone menarche, and improve final adult height.2,3

Many of the past studies concerning the auxological effect of treatment with GnRH agonist in CPP have focused on final height outcomes, and less attention has been paid to the body weight changes in this population of patients. Also, nutrition and body fat mass during childhood have been closely associated with early puberty, and recent publications have presented a more than doubled prevalence of overweight among youth in the United States in the recent two decades. In this respect, the importance of the effect of GnRH agonist treatment on body weight is clearly growing.4-7 Published data have demonstrated an increase in body mass index (BMI) during treatment with GnRH agonist, particularly in those with precocious puberty due to hypothalamic hamartoma.8,9 However, other reports suggested a reduction of BMI under gonadotropin-suppressive therapy or weight excess that does not seem to be significantly affected by GnRH agonist treatment.10,11

In this study, we investigated the height and BMI of patients treated with GnRH agonist for CPP.

This retrospective study was done by reviewing the medical records of 38 girls with CPP. The patients were treated with GnRH agonist for at least 18 months. The majority of the patients (35 girls) had idiopathic CPP. Organic CPP was diagnosed in 3 patients as the result of hypothalamic hamartoma, Rathke's cleft cyst, and hydrocephalus. CPP was defined as follows: i) the onset of secondary sexual characteristics before 8 years of age in girls, ii) accelerated growth rate, iii) advanced bone age of 1 year more than chronological age, and iv) a pubertal response to exogenous GnRH (gonadorelin 100 µg intravenous injection) with a peak luteinizing hormone (LH) level above 5 IU/L. Subjects were excluded from the analysis if they had any additional conditions that might affect puberty onset or BMI (e.g., hypothyroidism, growth hormone deficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia).

The GnRH stimulation test for diagnosing CPP was performed by injecting 100 µg of GnRH (Relefact; Sanofi-Aventis, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Blood samples were obtained immediately before the injection and at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after the injection. Serum LH, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and estradiol were measured by direct chemiluminescence with the ADVIA Centaur® Immunoassay System (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Tarrytown, NY, USA). The detection limits for LH, FSH, and estradiol were 0.07 IU/L, 0.6 IU/L, and 10 pmol/L, respectively. A stimulated LH value above 5 IU/L was considered diagnostic for CPP. Subcutaneous injection of GnRH agonist (leuprorelin acetate) was administered to the patients every 28 days at a dose of 30-90 µg/kg per injection. We evaluated height, weight, BMI, and bone age before and 12 and 18 months after GnRH agonist treatment. Bone age was assessed according to the Greulich-Pyle method12 and sexual maturation was classified according to the Marshall-Tanner method.1 Predicted adult height (PAH) was calculated according to the Bayley-Pinneau method.13 Mid-parental height was calculated by subtracting 6.5 cm to the mean of parental heights. Height and BMI standard deviation scores (SDS) for chronological age and bone age were calculated.

Statistical analyses were performed by using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software package for Windows (version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All values are given as mean±standard deviation and the paired t-test was used to compare the data. In the case of longitudinal comparisons of the same parameter, repeated-measures ANOVA was performed. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

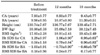

The age of initial manifestation of secondary sexual characteristics was 7.20±1.02 years, and the mean age of diagnosis and treatment was 7.93±0.77 years. Treatment was delayed in most girls because of the prolonged procedure for referral from the primary care doctors to our department. Bone age before treatment was 9.98±0.95 years, which was 2.05±0.65 years more than chronological age. Height SDS for chronological age was 1.29±0.97, and height SDS for bone age was -1.03±0.91. BMI SDS for chronological age was 0.58±1.18, and BMI SDS for bone age was 0.18±0.96 (Table 1). At 12 months after treatment, the difference between bone age and chronological age was 1.88±0.63 years, which was lower than the difference before treatment. PAH before treatment was 157.78±6.45 cm and mid-parental height was 159.47±4.00 cm.

Basal LH and FSH values were 2.09±2.41 IU/L and 4.11±5.25 IU/L, respectively. Peak LH and FSH levels were 22.87±12.61 IU/L and 15.47±6.79 IU/L, respectively. The peak LH/FSH ratio was 1.37±0.86. During the treatment period, we observed arrest or regression of clinical symptoms of gonadarche.

The height SDS adjusted for chronological age decreased from 1.29±0.97 at the onset of treatment to 1.06±0.90 at 12 months (p=0.006) and to 0.98±0.83 at 18 months (p<0.001). The height SDS for chronological age significantly decreased over time by use of repeated-measures ANOVA (p<0.001). However, the height SDS adjusted for bone age increased from -1.03±0.91 at the beginning of treatment to -0.73±0.90 at 12 months (p=0.004) and to -0.66±0.79 at 18 months (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1, 2). The height SDS for bone age significantly increased over time by use of repeated-measures ANOVA (p<0.001). The PAH significantly increased from 157.78±6.45 cm before treatment to 161.41± 8.97 cm at 12 months after treatment (p=0.015).

The BMI SDS for chronological age was significantly increased at 12 months (0.79±0.84, p=0.049) and at 18 months (0.96±0.83, p=0.048) compared with the BMI SDS at the beginning of treatment (0.58±1.18). The BMI SDS for chronological age significantly increased over time by use of repeated-measures ANOVA (p=0.025). The BMI SDS for bone age increased at 12 months after treatment, but the increase was not significant (Fig. 1, 2). According to their weight before treatment, girls were classified as overweight (group 1, n=12, BMI ≥85 percentile) and normal weight (group 2, n=26, BMI <85 percentile). The BMI SDS of normal-weight girls increased more than that of overweight girls, but the increase was not significant.

CPP may have profound physical and psychological effects on affected children and their families. It is accompanied by growth acceleration, advancement of bone age, and elevated sex steroid hormone levels for age. Therefore, early menarche and significant impairment of final height can result in untreated CPP patients. It is estimated that precocious puberty affects between 1 in 5,000 and 1 in 10,000 children, and CPP occurs at least 10-fold more frequently in girls than in boys; in more than 90% of girls, sexual precocity is idiopathic. Mogensen et al.14 reported a significant increase in the number of CPP patients over the recent 16-year period. This trend also occurred in Korean girls with a 4- to 5-fold increment in CPP patients over the recent 5-year period.15

GnRH agonist treatment in girls with CPP is reported to be effective in postponing the progression of puberty and the rapid bone maturation and in increasing the final adult height.2,3 However, there have been no randomized controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of GnRH agonist treatment; most studies compared PAH before treatment with the actual final adult height by a direct method.16 Klein et al.17 reported on 98 children with precocious puberty over a 2-year trial period of GnRH agonist treatment. The final height of 80 girls among these children averaged 159.8±7.6 cm (-0.6±1.3 SDS), which was greater than the pretreatment PAH of 149.3±9.6 cm (-2.4±1.6 SDS). The final height of 18 boys among these children averaged 171.1±8.7 cm (-0.8±1.3 SDS), which was also greater than the pretreatment PAH of 156.1±14.2 cm (-3.1±2.1 SDS). Thus, that study showed that the actual final adult height of both girls and boys was significantly higher than pretreatment PAH. Heger et al.18 also reported on 50 girls with precocious puberty over a 2-year trial period of GnRH agonist treatment. The final height of these children averaged 160.6±8.0 cm (-0.6±1.3 SDS), which was significantly greater than the pretreatment PAH of 154.9±9.6 cm. In this study, the PAH increased from 157.78±6.45 cm to 161.41±8.97 cm over the 1-year interval of treatment.

Weise et al.19 analyzed the growth of 100 girls during GnRH agonist treatment of CPP patients. In that study, the height SDS for chronological age tended to decrease after GnRH agonist treatment; this impaired growth abnormality was due to excessive advancement in growth plate senescence, induced by a prior rise of estrogen exposure. Meanwhile, the height SDS for bone age tended to increase after treatment. Those authors suggested bone age as a strong surrogate marker for growth plate senescence during GnRH agonist treatment. In the present study, we measured the height of patients during GnRH agonist treatment and compared this with pretreatment height. The height SDS for chronological age decreased from 1.29±0.97 at the onset of treatment to 1.06±0.90 at 12 months and to 0.98±0.83 at 18 months. When the height SDS was adjusted for bone age, a remarkable increase in growth was found from -1.03±0.91 at the beginning of treatment to -0.73±0.90 at 12 months and -0.66±0.79 at 18 months.

Even though studies have been published on the issue of obesity during GnRH agonist treatment, there is much discussion.9,20,21 During normal physical development, the BMI of a female child increases in the first year of life, is then reduced until 4 years of life, and thereafter it seems to increase again until adulthood. Therefore, pediatric obesity could be overlooked in the 6-year-old age group with an increased BMI SDS; thus, attention should be paid to potential patients who may have CPP. Several studies have reported that percentage of fat mass, percentage body fat SDS for chronological age, and BMI SDS for chronological age increase during GnRH agonist treatment in CPP patients.9,20 Oostidijk et al.21 reported that BMI SDS for chronological age and bone age increased during GnRH agonist treatment in CPP patients. In other studies, however, GnRH agonist treatment in CPP patients did not induce significant changes in BMI SDS, and obesity was not related to GnRH agonist administration.10,11 After GnRH agonist treatment, increases in body weight and BMI SDS in CPP patients occur in most overweight patients.22 But Aguiar et al.23 reported that the BMI SDS increased significantly more in normal-weight girls than in overweight girls during GnRH agonist treatment. In this study, the BMI SDS for chronological age was significantly increased at 12 months (0.79±0.84) and at 18 months (0.96±0.83) when compared with the BMI SDS at the beginning of treatment (0.58±1.18). The BMI SDS for bone age increased at 12 months after treatment, but the increase was not significant. The BMI SDS of normal-weight girls increased more than that of overweight girls, but this increment was not significant. To prove this trend, additional data acquisition and a long-term follow-up study are needed.

In summary, the height SDS for bone age significantly increased during GnRH agonist treatment in our patients, and the PAH was also increased after treatment. Furthermore, the BMI SDS for chronological age increased significantly. For ethical reasons, clinical trials using GnRH agonist to treat CPP have not included placebo control groups. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether increased BMI is a result of the therapy or is an expected manifestation of the primary process. Preventive measures, such as increased physical activity, can be introduced to minimize possible alterations in body weight, and a long-term follow-up study is required to elucidate whether GnRH agonist treatment in Korean girls with CPP affects adult obesity.

Figures and Tables

| FIG. 1Changes in the height SDS and BMI SDS for chronological age during GnRH agonist treatment. *p< 0.05 compared to before treatment. BMI: body mass index, HT: height, SDS: standard deviation score, CA: chronological age. |

References

1. Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969. 44:291–303.

2. Carel JC, Lahlou N, Roger M, Chaussain JL. Precocious puberty and statural growth. Hum Reprod Update. 2004. 10:135–147.

3. Kauli R, Galatzer A, Kornreich L, Lazar L, Pertzelan A, Laron Z. Final height of girls with central precocious puberty, untreated versus treated with cyproterone acetate or GnRH analogue. A comparative study with re-evaluation of predictions by the Bayley-Pinneau method. Horm Res. 1997. 47:54–61.

4. Dunger DB, Ahmed ML, Ong KK. Effects of obesity on growth and puberty. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005. 19:375–390.

6. Troiano RP, Flegal KM. Overweight prevalence among youth in the United States: why so many different numbers? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999. 23:Suppl 2. S22–S27.

7. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006. 295:1549–1555.

8. Carel JC, Roger M, Ispas S, Tondu F, Lahlou N, Blumberg J, et al. Final height after long-term treatment with triptorelin slow release for central precocious puberty: importance of statural growth after interruption of treatment. French study group of Decapeptyl in Precocious Puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999. 84:1973–1978.

9. Feuillan PP, Jones JV, Barnes K, Oerter-Klein K, Cutler GB Jr. Reproductive axis after discontinuation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog treatment of girls with precocious puberty: long term follow-up comparing girls with hypothalamic hamartoma to those with idiopathic precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999. 84:44–49.

10. Arrigo T, De Luca F, Antoniazzi F, Galluzzi F, Segni M, Rosano M, et al. Reduction of baseline body mass index under gonadotropin-suppressive therapy in girls with idiopathic precocious puberty. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004. 150:533–537.

11. Lebrethon MC, Bourguignon JP. Management of central isosexual precocity: diagnosis, treatment, outcome. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000. 12:394–399.

12. Greulich WW, Pyle SI. Radiographic atlas of skeletal development of the hand and wrist. 1959. 2nd ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

13. Bayley N, Pinneau SR. Tables for predicting adult height from skeletal age: revised for use with the Greulich-Pyle hand standards. J Pediatr. 1952. 40:423–441.

14. Mogensen SS, Aksglaede L, Mouritsen A, Sørensen K, Main KM, Gideon P, et al. Diagnostic work-up of 449 consecutive girls who were referred to be evaluated for precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011. 96:1393–1401.

15. Kim HK, Kee SJ, Seo JY, Yang EM, Chae HJ, Kim CJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation test for precocious puberty. Korean J Lab Med. 2011. 31:244–249.

16. Mul D, Hughes IA. The use of GnRH agonists in precocious puberty. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008. 159:Suppl 1. S3–S8.

17. Klein KO, Barnes KM, Jones JV, Feuillan PP, Cutler GB Jr. Increased final height in precocious puberty after long-term treatment with LHRH agonists: the National Institutes of Health experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001. 86:4711–4716.

18. Heger S, Partsch CJ, Sippell WG. Long-term outcome after depot gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment of central precocious puberty: final height, body proportions, body composition, bone mineral density, and reproductive function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999. 84:4583–4590.

19. Weise M, Flor A, Barnes KM, Cutler GB Jr, Baron J. Determinants of growth during gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog therapy for precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004. 89:103–107.

20. Boot AM, De Muinck Keizer-Schrama S, Pols HA, Krenning EP, Drop SL. Bone mineral density and body composition before and during treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist in children with central precocious and early puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998. 83:370–373.

21. Oostdijk W, Rikken B, Schreuder S, Otten B, Odink R, Rouwé C, et al. Final height in central precocious puberty after long term treatment with a slow release GnRH agonist. Arch Dis Child. 1996. 75:292–297.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download