Abstract

The Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea recently designated cerebrovascularspecified centers (CSCs) to improve the regional stroke care system for acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients. This study was performed to evaluate the changes in the flow of AIS patients between hospitals and to describe the role of the Emergency Medical Information Center (EMIC) after the designation of the CSCs. Data for coordination of interhospital transfers by the EMIC were reviewed for 6 months before and after designation of the CSCs. The data included the success or failure rate, the time used for coordination of interhospital transfer, and the changes in the interhospital transfer pattern between transfer-requesting and transfer-accepting hospitals. The total number of requests for interhospital transfer increased from 198 to 244 after designation of the CSCs. The median time used for coordination decreased from 8.0 minutes to 4.0 minutes (p<0.001). The success rate of coordination increased from 88.9% to 96.7% (p<0.001). The proportion of requests by CSCs decreased from 3.5% to 0.4% (p=0.017). However, the proportion of acceptance by non-CSC hospitals increased from 15.9% to 25.8% (p=0.015). With the designation of CSCs, the EMIC could coordinate interhospital transfers more quickly. However, AIS patients are more dispersed to CSC and non-CSC hospitals, which might be because the CSCs still do not have sufficient resources to cover the increasing volume of AIS patients and non-CSC hospitals have changed their policies. Further studies based on patients' outcome are needed to determine the adequate type of interhospital transfer for AIS patients.

The development of comprehensive stroke centers within hub-and-spoke stroke networks has been recommended to improve stroke care and to increase the utilization of approved therapies.1 Within these networks, eligible patients from community or primary stroke centers could be transferred to comprehensive stroke centers for acute management. The Ministry of Health and Welfare designated 28 Cerebrovascular-Specified Centers (CSCs), Major Trauma-Specified Centers, and Cardiovascular-Specified Centers in April 2010 as a result of preliminary designation in May 2009. With the designation of a hospital as a "center," the government has started to support the resources and administrative changes necessary to establish a service for such time-sensitive conditions.2 High-level centers are equipped with the workforce, facilities, and instruments needed to diagnose and treat more complex patients. However, recently, there was social concern that emergency patients were left to wander among major hospitals. Delays occurred in finding available facilities owing to a weak coordination system for interhospital transfer. As seen in a study on trauma centers, exhaustion of medical resources in high-level trauma centers owing to overcrowding is related to worse outcomes of patients and high social expenses.3,4 It seems that it is theoretically possible that the same situation could occur in the care of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients. Some AIS patients admitted to small hospitals need to be transferred to highly qualified stroke centers. Optimal matching of the patient's needs with hospital capabilities relies on appropriate transfer to the high-level centers as well as the back-transport of patients from high-level centers to community hospitals. To get the right patient to the right hospital in the right time to improve patient outcome, an organized and coordinated approach is needed.5 In Busan and Ulsan metropolitan cities, the Busan Emergency Medical Information Center (EMIC) has been performing the coordination for interhospital transfers since 2001. The purpose of this study was to evaluate changes in the flow of AIS patients and the role of the EMIC in a regional stroke care system.

This was a pre- and post- observational study designed to assess the effect of designation of a CSC on the flow of AIS patients and the coordination for interhospital transfer by Busan EMIC. The study was deemed exempt from review and informed consent by the institutional review board at the hospital site because of the observational nature of the study.

Busan EMIC has been operating under the control of the Busan Wide Regional Emergency Center by the Ministry of Health and Welfare since 2001. The Busan EMIC is in charge of Busan and nearby Ulsan metropolitan cities with a combined population of 4.7 million (Busan: 3.6 million, 766 km2; Ulsan: 1.1 million, 1,057 km2). The area has 43 designated emergency medical centers. It includes 3 CSCs in Busan and 1 CSC in Ulsan. The Busan EMIC has been coordinating inquiries of laypersons, ambulance crews, and medical providers to search for available hospitals on a 24/7 basis. Most of the coordination is performed by emergency medical technicians under the supervision of board-certificated physicians.

The receiving hospital was contacted on the basis of being the nearest appropriate hospital. Busan EMIC has data on the level of hospitals such as CSCs and non-CSCs. They had been using data on the availability of computed tomography, ventilators, and beds in the emergency room and intensive care unit through the internet to search for receiving hospitals. In the first step, the hospitals to contact were chosen by matching the medical need of the patient, the level of the receiving hospital, and the distance between transferring and receiving hospitals. The EMIC also has the cellular phone number of designated vascular neurologists and physicians in the emergency department on a volunteer basis. Emergency medical providers are able to inquire about interhospital transfers through a single phone number of 1339. In the second step, permission for the interhospital transfer is granted by the vascular neurologist or physician in the emergency department of the receiving hospital under the coordination of the EMIC. Sometimes, several calls are needed to find an available hospital for interhospital transfer. The number, time, and the content of each call for interhospital transfer are automatically recorded in the electrical database of Busan EMIC.

Data on interhospital transfers of AIS patients by the EMIC were reviewed for 6 months before (from December 2008 to March 2009) and 6 months after (from December 2010 to March 2011) the designation of the CSCs, respectively. Diagnosis was based on the requesting physician. We defined a request as a call to EMIC that required interhospital transfer. Definition of acceptance was the granting of permission for interhospital transfer by the accepting hospital. The data included the success or failure of coordination for interhospital transfer, the time consumed for coordination, and the name of the requesting and accepting hospitals.

Data were analyzed by using PASW 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Analyses for continuous and categorical variables were performed by using the Student's t- or Mann-Whitney U test and chi-square (or Fisher's exact) test, respectively. All tests for significance were two-tailed with an alpha level of 0.05.

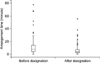

During the pre- and post-designation study periods, there were 198 and 244 interhospital transfers of AIS patients coordinated by the Busan EMIC, respectively. The most common age range was the 70s (25.9%). The distribution of ages was as follows (in sequence): 70s (25.9%), 60s (22.9%), 50s (20.6%), above 80s (13.4%), 40s (12.9%), and 30s (2.9%). We compared the median time used for coordination of interhospital transfers in the pre-designation study period with that of the post-designation study period. After the designation of the CSCs, the time decreased from 8.0 minutes to 4.0 minutes (p<0.001, Fig. 1). The success rate of coordination for interhospital transfer increased from 88.9% to 96.7% (p<0.001, Table 1). The requests for interhospital transfer increased with the designation of the CSCs, but the proportion of CSCs decreased from 3.5% to 0.4% (p=0.025, Table 2). With the designation of the CSCs, the proportion of acceptance for interhospital transfer by non-CSC hospitals increased from 15.9% to 25.8% (p=0.015, Table 2).

Construction of a regional stroke care system improves outcome.6-9 Concepts for the development of a regional care system for time-sensitive conditions such as trauma, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease are similar in many aspects. However, in contrast with a trauma system, which has a long history of evolution, the concept of a stroke care system is only recently developed and reflects the latest concepts of the trauma system.10,11 The concept of the trauma system has evolved from getting "injured patients to the nearest facilities quickly" to "severely injured patients to definitive care facilities quickly" to "the right patients to the right facilities in the right time."12 Before the 1970s, trauma patients were transported to the nearest facilities without field triage. In the 1970s, patients with major injuries began to be concentrated in high-level trauma centers according to the exclusive trauma system. The system was based on the concept that a better outcome would come from more experienced facilities with a large volume of injured patients where trauma teams provide coordinated resuscitation, evaluation, and definitive treatment.2 Therefore, acute care facilities need to be categorized according to their ability to provide care, and patients are distributed to facilities at each level of care according to severity. In reality, however, patients with minor injuries were concentrated at high-level centers owing to over-triage at the prehospital and interhospital transfer level. Overcrowding of high-level centers resulted in exhaustion of medical resources, wasting of social resources, and worse outcomes. Thus, some trauma centers did not want to receive more patients.13-15 In contrast with older statistics that compared high-level centers and small hospitals in a region, expanded statistics could compare hospitals among regions with different trauma systems. In the 1990s, the concept of inclusive trauma systems was introduced. These systems were designed to care for all injured patients in a given geographical area. Therefore, all acute care hospitals were expected to participate in a trauma system as one of the multi-level centers from level I to III or V.16 In the inclusive trauma system, collaboration should exist between the government, emergency medical services, and acute care hospitals.17 However, the inclusion system also has theoretical disadvantages. Spreading the volume of trauma care among centers may diminish providers' experience and efficiency of care in high-level centers. The inclusive system may also delay definitive care for patients who should have been triaged directly from the injury scene or should have been transferred to a high-level center after their initial evaluation at a small hospital.

The present study addressed two components of the stroke system. First is the infrastructure of the regional stroke care system. The internal change in designated hospitals would be reflected in the interhospital transfer pattern. Second is the interhospital transfer system itself. In the well-organized stroke care system, any hospital in the stroke care system that provides emergency department services should be able to function as a primary stroke center or in the rapid transfer of appropriate patients through the use of prenegotiated interhospital protocols, transfer agreements, and transport protocols.10 Theoretically, the receiving hospitals are decided by the system itself. In practice, however, there should be an agreement on interhospital transfer between the transferring and the receiving physicians and there may be several trials to find the final receiving hospital.18 Recently, consensus has been reached that the formal transfer system is not enough. System-level coordination is needed.4 With respect to agreement, there can be 3 types of interhospital transfer when a hospital decides to transfer stroke patients. The first is no agreement or even no contact between transferring and receiving physicians. The second is direct contact between physicians. The third is contact via the EMIC.

An EMIC for coordination is a relatively new concept. Epley et al reported on an organized system combining a communications center with a formal interhospital transfer system of trauma patients.13 Before the activation of the communication center, the interval from the transfer decision to the acceptance decision was 30.5 minutes conservatively. In fact, there were anecdotal cases of 6 to 12 hours. With the activity of a communication center, the interval decreased to 10.0 minutes. The necessity of coordination has been described in interhospital transfer of ST elevation myocardial infarction. Coordination with a single phone number has decreased the time from visiting former hospitals to balloon angioplasty at later hospitals.19,20 This has been described in other time-sensitive conditions as well. In AIS patients, prior notice to the receiving vascular neurologist via the Busan EMIC has decreased the door-to-needle time for intravenous thrombolysis in a hospital.21 In contrast with the lately developed concept of a stoke system based on a multi-level stroke center, our regional stroke care system is based on the earlier concept of a single high-level center. Several components of the formal system for getting "the right patients to the right facilities in the right time" were short in our regional stroke care system. After our designation of a CSC, the requests for interhospital transfer from the CSC decreased. This reflects internal changes within the CSC, which wants to treat more AIS patients. However, the proportion of acceptance by the CSCs decreased despite the increasing volume of AIS patients. AIS patients were dispersed more to non-CSC hospitals. These findings might be explained by the fact that the CSCs still do not have sufficient resources to cover the increasing volume of AIS patients, and the designation of a CSC might encourage non-CSC hospitals to accept AIS patients more easily so as not to lose some AIS patients. The success rate of coordination for interhospital transfer increased and the time used for coordination decreased after designation of the CSCs. The EMIC might have been able to arrange for faster transfers because competition for referrals from the coordinating center encourages hospitals to cooperate with the EMIC.

These results also suggest that the Busan EMIC has a properly coordinated network for interhospital transfer in our regional stroke care system.

However, our study had several limitations. There could be regions where large, overcrowded designated CSCs do not want to treat more AIS patients. Furthermore, dispersion of AIS patients to CSC or non-CSC hospitals could have positive or negative effects on the patients' outcome. In fact, even in the trauma system with its long history, interhospital transfer is called a "curse" of registry.22 Uniform data templates and data input on a regional basis would be other problems.23 Also, the stroke system has just began to evolve. There would be a long journey of evolution to relieve the scientific gap. At any rate, our study is not related to patient outcomes but to stroke center designation and patient flow. Another limitation is that internationally, there is no single, simple way in which to enact a regional stroke care system for AIS patients. Like other studies of such systems, our results also cannot be generalized.

In conclusion, with the designation of CSCs, the EMIC could coordinate interhospital transfer more quickly. The CSCs wanted to treat more AIS patients. However, we also found that AIS patients were dispersed to both CSC and non-CSC hospitals in our region. These results might be explained by the fact that the CSCs still do not have sufficient resources to cover the increasing volume of AIS patients, or that not only CSCs but also some non-CSC hospitals wanted to treat more patients. Further studies based on patients' outcomes are needed to determine the adequate type of interhospital transfer for AIS patients.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Alberts MJ, Latchaw RE, Selman WR, Shephard T, Hadley MN, Brass LM, et al. Brain Attack Coalition. Recommendations for comprehensive stroke centers: a consensus statement from the Brain Attack Coalition. Stroke. 2005. 36:1597–1616.

2. Boyd DR, Cowley RA. Comprehensive regional trauma/emergency medical services (EMS) delivery systems: the United States experience. World J Surg. 1983. 7:149–157.

3. Harrington DT, Connolly M, Biffl WL, Majercik SD, Cioffi WG. Transfer times to definitive care facilities are too long: a consequence of an immature trauma system. Ann Surg. 2005. 241:961–966.

4. Glickman SW, Kit Delgado M, Hirshon JM, Hollander JE, Iwashyna TJ, Jacobs AK, et al. 2010 Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference Beyond Regionalization: Intergrated Networks of Emergency Care. Defining and measuring successful emergency care networks: a research agenda. Acad Emerg Med. 2010. 17:1297–1305.

5. West JG, Trunkey DD, Lim RC. Systems of trauma care. A study of two counties. Arch Surg. 1979. 114:455–460.

6. LaMonte MP, Bahouth MN, Magder LS, Alcorta RL, Bass RR, Browne BJ, et al. Emergency Medicine Network of the Maryland Brain Attack Center. A regional system of stroke care provides thrombolytic outcomes comparable with the NINDS stroke trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2009. 54:319–327.

7. Gropen TI, Gagliano PJ, Blake CA, Sacco RL, Kwiatkowski T, Richmond NJ, et al. NYSDOH Stroke Center Designation Project Workgroup. Quality improvement in acute stroke: the New York State Stroke Center Designation Project. Neurology. 2006. 67:88–93.

8. Stradling D, Yu W, Langdorf ML, Tsai F, Kostanian V, Hasso AN, et al. Stroke care delivery before vs after JCAHO stroke center certification. Neurology. 2007. 68:469–470.

9. LaBresh KA, Reeves MJ, Frankel MR, Albright D, Schwamm LH. Hospital treatment of patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack using the "Get With The Guidelines" program. Arch Intern Med. 2008. 168:411–417.

10. Stoeckle-Roberts S, Reeves MJ, Jacobs BS, Maddox K, Choate L, Wehner S, et al. Closing gaps between evidence-based stroke care guidelines and practices with a collaborative quality improvement project. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006. 32:517–527.

11. Leifer D, Bravata DM, Connors JJ 3rd, Hinchey JA, Jauch EC, Johnston SC, et al. American Heart Association Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council. Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Working Group. Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia. Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. Metrics for measuring quality of care in comprehensive stroke centers: detailed follow-up to Brain Attack Coalition comprehensive stroke center recommendations: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011. 42:849–877.

12. Guidelines for Field Triage of Injured Patients. Recommendations of the national expert panel on field triage. 2011. 06. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5801.pdf.

13. Epley EE, Stewart RM, Love P, Jenkins D, Siegworth GM, Baskin TW, et al. A regional medical operations center improves disaster response and inter-hospital trauma transfers. Am J Surg. 2006. 192:853–859.

14. Esposito TJ, Crandall M, Reed RL, Gamelli RL, Luchette FA. Socioeconomic factors, medicolegal issues, and trauma patient transfer trends: Is there a connection? J Trauma. 2006. 61:1380–1386.

15. Parks J, Gentilello LM, Shafi S. Financial triage in transfer of trauma patients: a myth or a reality? Am J Surg. 2009. 198:e35–e38.

16. Position paper on trauma care systems. Third National Injury Control Conference April 22-25, 1991, Denver, Colorado. J Trauma. 1992. 32:127–129.

17. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Model trauma system planning and evaluation. 2006. cited 2011 July 1. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services;Available from: http://www.kstrauma.org/download/ModelTraumaSystem-PlanningandEvaluation.pdf.

18. Schwamm LH, Pancioli A, Acker JE 3rd, Goldstein LB, Zorowitz RD, Shephard TJ, et al. American Stroke Association's Task Force on the Development of Stroke Systems. Recommendations for the establishment of stroke systems of care: recommendations from the American Stroke Association's Task Force on the Development of Stroke Systems. Stroke. 2005. 36:690–703.

19. Ting HH, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, Haro LH, Bjerke CM, Lennon RJ, et al. Regional systems of care to optimize timeliness of reperfusion therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the Mayo Clinic STEMI Protocol. Circulation. 2007. 116:729–736.

20. Henry TD, Unger BT, Sharkey SW, Lips DL, Pedersen WR, Madison JD, et al. Design of a standardized system for transfer of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction for percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2005. 150:373–384.

21. Kim SK, Lee SY, Bae HJ, Lee YS, Kim SY, Kang MJ, et al. Pre-hospital notification reduced the door-to-needle time for iv t-PA in acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2009. 16:1331–1335.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download