Abstract

Penetrating neck injuries are potentially dangerous and require emergent management because of the presence of vital structures in the neck. Penetrating vascular trauma to zone I and III of the neck is potentially life-threatening. An accurate diagnosis and adequate surgical intervention are critical to the successful outcome of penetrating trauma in the neck. We experienced some cases with externally penetrating injuries in neck zone II in which the patients were confirmed to have the presence of large vessel injuries in neck zones I and III. Here we report on the endovascular stent techniques used in two cases to address penetrating carotid artery injuries and review the literature.

In the neck, various vital structures, such as blood vessels, respiratory organs, and parts of the digestive system, nervous system, and endocrine system, are present in a narrow space. The neck is not protected by the skeleton and is vulnerable to external trauma. A penetrating trauma occurring in the neck can cause severe complications such as hemorrhage as the result of vascular injury, spinal cord injury, respiratory obstruction, and sepsis from esophageal injury. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential.1-5

In cases of penetrating injury occurring in zones I and III of the neck, the direct control of blood vessels is difficult. The intrathoracic or extracorporeal presence of hemorrhage may lead to fatal injuries. Accordingly, unlike the situation in zone II of the neck, where the proximal and distal control of blood vessels can be easily achieved, angiography should be performed in cases of penetrating injury occurring in zones I and III.1,4 In cases of penetrating neck injury, however, the neck zone cannot be accurately differentiated by means of the external wound only. We successfully treated patients who had externally penetrating injuries in neck zone II and were confirmed to have the concurrent presence of large vessel injuries in neck zones I and III by inserting an endovascular stent in an urgent interventional angiography procedure. Here, we report our cases with a review of the literature.

A 72-year-old man who fell off a glass door and had a neck laceration visited our hospital. On arrival at the emergency room, the patient had a laceration of approximately 7 cm in length in the anterior area of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and in neck zone II. At the time of the patient's visit, his blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg and his pulse was 66 beats/minute. His hemoglobin level was measured at 4.9 mg/dl. The patient was supplied with a massive amount of fluid and 12 units of packed red blood cells. Under suspicion of a large vessel injury occurring in neck zone II, a computed tomography (CT) angiography was performed, which showed that the patient had a hematoma in the neck and the peritracheal area. The patient was suspected to have a carotid artery laceration in neck zone I accompanied by a pulsating hemorrhage (Fig. 1). Angiography was immediately performed via the femoral artery. The presence of contrast leakage was confirmed in the common carotid artery, which was 3 cm superior to the innominate artery bifurcation. A guided catheter was passed by means of a 10-mm balloon angioplasty. A stent (Jostent peripheral stent-graft, 4-9 mm range, 25 mm length, Abbott Laboratories, Abbot Park, IL, USA) was then inserted. Thereafter, with the patient under general anesthesia, the neck laceration site was explored, the hematoma removed, another bleeding focus checked, and lack of other injuries confirmed. On the day following the intervention, CT angiography was performed, which confirmed that the stent was well maintained in its original location (Fig. 2). At 12 months after the penetrating neck injury, the patient was prescribed an antiplatelet drug. The patient experienced no complications and is under follow-up observation at our outpatient clinic.

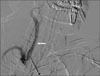

A 35-year-old man visited the emergency room with multiple cervicofacial lacerations due to a broken beer bottle. At the time of the patient's visit, his blood pressure was 70/40 mmHg, his pulse 110 beats/minute, and his hemoglobin level 4.7 mg/dl. Major sites of injury included the anterior part of neck zone II. There were multiple lacerations and a copious hemorrhage on the right side (Fig. 3). Because of hypovolemic shock, he displayed signs of confusion. Accordingly, the patient was supplied with a massive amount of fluid and 39 units of packed red blood cells. The patient was suspected to have a vascular injury in neck zone II. CT angiography was performed and the CT scan showed contrast leakage in the right internal carotid artery. Under suspicion of a penetrating neck injury accompanied by internal carotid artery laceration, angiography was performed via the right femoral artery. The findings on angiography were suggestive of extravasation of contrast media in neck zone III (Fig. 4A). Therefore, a stent was inserted in the laceration site and, under general anesthesia, the patient's neck laceration site was explored, the hematoma removed, another bleeding focus checked, and lack of other injuries confirmed. On the day following stent insertion, angiography showed lack of contrast leakage in the right internal carotid artery (Fig. 4B). At 12 months after the injury, the patient received an antiplatelet drug. There have been no special findings and the patient is under follow-up observation at our outpatient clinic.

Neck injuries are divided into three anatomical zones (Fig. 5). Control of blood vessels is difficult in cases of vascular injuries occurring in zone I. With the presence of intrathoracic or extracorporeal hemorrhage, hypovolemic shock may occur until the damaged blood vessels are controlled. Zone II is the most common site of carotid artery injury, where there is often a tendency for the hematoma to be compressed and maintained by the fascial layers of the neck following hemorrhage. Through neck exploration, control of the proximal and distal injured blood vessels is easily achieved. In zone III, structures such as the distal part of the carotid artery, the vertebral artery, the parotid gland, the pharynx, the vertebra, and cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII are present. In cases of penetrating injury occurring in this zone, multiple vascular and cranial nerve injuries often occur. In zone III, it is not easy to access the hemorrhage site, which is also difficult to manage because of the narrow view.

Vascular neck injury causes massive hemorrhage, which abruptly reaches a physiologically irreversible status accompanied by multiple organ injury. Immediate airway security, acquisition of a fluid line route, and hemodynamic management should precede diagnosis or surgery. The most common symptoms from which vascular injuries can be clinically suspected include hematoma and external hemorrhage.6 Diagnosis of vascular injury requires an investigation of the patient's history and symptoms, as well as findings from physical examinations, simple X-rays, CT scan, angiography, and Doppler ultrasound. Angiography is the most accurate method for cases in which a vascular neck injury is suspected. The test cannot be performed in some cases, however, depending on the systemic status of the patient and the risk of intervention. Nevertheless, angiography has been selectively used in cases in which the hemorrhage site needs to be confirmed.7 With the latest advances in technology, angiography is not restricted to diagnosis of vascular injury. Cases in which a vascular injury is confirmed by angiography are treated without surgical management immediately after the stent is inserted.

In general, in diagnosing vascular injury due to neck laceration, angiography is performed in cases of injury occurring in zones I and III.2 In cases of injury in zone II with the concurrent presence of neurological symptoms, angiography is necessary, but if no neurological symptoms are present, the laceration site is confirmed only through neck exploration. However, in our cases, even when the external penetration site corresponded to zone II, the injury was confirmed as being in zones I and III. As a result, surgical access was difficult. In other words, in cases of injury occurring as a result of the use of sharp materials such as glass or a knife, the neck zone where the laceration appears to be from the external aspect may be different from where large vessels are in fact damaged. Thus, even in cases of laceration occurring in neck zone II, if a vascular neck injury is suspected, angiography should be performed to concomitantly perform diagnosis and treatment.

In cases in which a vascular injury is diagnosed, conservative treatments such as observation or anticoagulant drugs, surgical treatments such as vessel ligation or revascularization, and interventional procedures such as stent insertion should be considered. In cases of vascular neck injury, the conventional palliative method is surgical treatment to suture the damaged vessels (angiography) when the damaged site is detected on angiography.8,9 In our cases, as a result of massive hemorrhage, the patients had hypovolemic shock or a failed angiography. The functions of the blood vessels themselves may be lost with the use of ligatures. The results of this procedure may also cause fatal outcomes or neurological symptoms in cases involving the carotid artery. Accordingly, in recent years, when vascular injury is diagnosed by use of angiography, angiography is not performed immediately using surgical treatment. Instead, insertion of a stent is first attempted. In the current cases, the damage to neck zone II was suspected from external findings. When angiography was performed to identify the actual damaged sites, however, the sites were confirmed to be in neck zones I and III. This was immediately followed by the insertion of a stent. Thereafter, with neck exploration, the inserted stent was confirmed to be well functioning. Moreover, the inner diameters of the inserted stents become altered depending on blood pressure, i.e., the hemodynamic fluctuation of patients. This implies that the current safety of stents has been increased and the risk minimized, both of which were problems disclosed for conventional types of stent.10

In conclusion, in cases of neck laceration in which vascular injury is suspected, even if the lesion is detected in zone II, the zones involving the affected blood vessels should first be identified through angiography rather than access via neck exploration. In cases in which large vessel injury is suspected, an endovascular stent technique should first be considered, with no respect to neck zones, because this would be beneficial for patients.

Figures and Tables

FIG. 1

The right carotid angiographic image shows extravasation of contrast media (arrow) from the proximal common carotid artery.

FIG. 2

Follow-up angiographic image shows a patent right internal carotid artery without leakage of contrast media. The angiographic image reveals the patent stent (arrow).

FIG. 4

The right carotid angiographic image (A) shows extravasation of contrast media (arrows) from the cervical internal carotid artery. After deployment of a balloon expandable stent graft, extravasation of contrast media is no longer demonstrated (B).

FIG. 5

Zones of the neck for classification of penetrating injuries. Zone I extends from the sternal notch to the cricoid cartilage. The thoracic inlet may be considered an inferior extension of this zone. Zone II extends from the cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible. Zone III extends from the angle of the mandible to the base of the skull.

References

1. Kim JP, Kim JW, Ahn SK, Jeon SY. A case of the zone III neck injury by impalement of a metal stick. Korean J Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2003. 46:610–612.

2. Perry MO, Snyder WH, Thal ER. Carotid artery injuries caused by blunt trauma. Ann Surg. 1980. 192:74–77.

3. Roon AJ, Christensen N. Evaluation and treatment of penetrating cervical injuries. J Trauma. 1979. 19:391–397.

5. Watson JM, Goldstein LJ. Golf club shaft impalement: case report of a zone III neck injury. J Trauma. 1996. 41:1036–1038.

6. Demetriades D, Theodorou D, Cornwell E, Berne TV, Asensio J, Belzberg H, et al. Evaluation of penetrating injuries of the neck: prospective study of 223 patients. World J Surg. 1997. 21:41–47.

7. Bell RB, Osborn T, Dierks EJ, Potter BE, Long WB. Management of penetrating neck injuries: a new paradigm for civilian trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007. 65:691–705.

8. Múnera F, Soto JA, Nunez D. Penetrating injuries of the neck and the increasing role of CTA. Emerg Radiol. 2004. 10:303–309.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download