Abstract

The perforation and subsequent panperitonitis as one of the complications of a Meckel diverticulum is a rare complication, especially in infants. Complication of Meckel diverticulum, preoperative and operative patient's mean age is about 5 years old. A 13-month-old male infant presented at our emergency room with currant jelly stool of about 24 hours duration. Intussusception or bacterial enteritis was initially suspected. Gastrointestinal ultrasonography showed no evidence of intussusception or appendicitis. On the 3rd hospital day, he suddenly showed high fever and irritability. Abdominal CT suggested intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal abscess with air collection due to possible bowel perforation. The final diagnosis of perforation of Meckel diverticulum was made by laparoscopy and biopsy. We report a very rare case with perforation of Meckel diverticulum in infant period.

In 1598, Fabricus Hildanus first identified an anatomic variant in ileum. However, Johann Meckel was the first to publish a detailed description of this common finding. Meckel diverticulum, a remnant of the vitelline duct, is found in 2% of the population. It is usually located on the anti-mesenteric border of the ileum, and within proximally about 60 cm from the terminal ileum. It is often found in children and less commonly present in the adult [1].

Meckel diverticulum originates when the omphalomesenteric duct fails to disappear around the seventh or eighth week of gestation. Finally, it is leads to several possible anomalies including omphalomesenteric fistula, enterocyst, fibrous band connecting the intestine to the umbilicus or a Meckel diverticulum with or without a fibrous cord connecting to the umbilicus. Anatomically, the Meckel diverticulum contains all layers of the small intestine, arising from the anti-mesenteric border of the ileum and receives blood supply from a remnant of the vitelline artery that emanates from the superior mesenteric artery [2].

Several cases with perforation of Meckel diverticulum have been reported in neonates, including a 5-day-old Korean neonatal case [3]. However, only one case has been reported in infants worldwide, with diagnosis on biopsy examination. A perforation of Meckel diverticulum rarely occurs in infants and is difficult to diagnose. Complication of Meckel diverticulum, preoperative and operative patient's mean age is about 5 years old. So, we report a case of 13-month-old infant with perforation of Meckel diverticulum that mimicked manifestation of intussusception.

A previously healthy 13-month-old male infant was transferred from an outside facility to our emergency room for a suspected intussusception. He initially presented at the outside facility with sudden onset of currant jelly stool. He had previously been in good health, with no fever or chills and normal bowel movements. There was no associated nausea, vomiting, or preceding viral illnesses. On physical exam, the child was resting comfortably in in seating position. General appearance was relatively good and mental state was alert. His vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 100/80 mmHg; heart rate, 70 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 36.5℃.

On palpation of the abdomen, he has some degree of rigidity, voluntary muscle guarding and mild tenderness in the periumbilical and right lower quadrant area. Bowel sounds were audible but diminished throughout. The other findings of physical exam was unremarkable and within normal limits for his age.

We immediately conducted abdominal X-ray and gastrointestinal ultrasonography for rule out of intussusception. But, there was no evidence of intussusception or appendicitis on gastrointestinal ultrasonography, with small amounts of fluid collection around small and large bowel (Fig. 1).

Laboratory data were as follows: sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 5.1 mEq/L; chloride, 100 mEq/L; BUN/creatinine, 21.6/0.3 mg/dL; CRP, 3 mg/dL; and glucose, 91 mg/dL. The complete blood cell count (CBC) was as follows: WBC count, 18,640/µL; neutrophils, 41.2%; hemoglobin/hematocrit (Hb/Hct), 10.8/32.1%; and platelets, 397,000/µL.

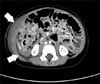

We considered this patient as bacterial enteritis and started symptomatic treatment. On the 3rd hospital day, the patient suddenly showed massive bloody stool. His vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 95/70 mmHg; heart rate, 93 beats/min; respiratory rate, 21 breaths/min; and temperature, 39.5℃. Physical examination on abdomen showed rigidity, voluntary guarding and tenderness on palpation in the entire abdominal area. Bowel sounds were decreased. Laboratory data were as follows: sodium, 140 mEq/L; potassium, 3.3 mEq/L; chloride, 102 mEq/L; BUN/creatinine, 2.7/0.32 mg/dL; CRP, 118 mg/dL; and glucose, 93 mg/dL. The CBC was as follows: WBC, 15,420/µL; neutrophils, 69.4%; Hb/Hct, 8.9/26.6%; and platelets, 346,000/µL. Abdominal CT showed suspicious intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal abscess with air collection due to possible bowel perforation (Fig. 2).

The consulting surgical team immediately performed an exploratory laparotomy. Under exploratory laparotomy, a 5 cm sized Meckel diverticulum was seen at proximal 50 cm from the ileocecal valve (Fig. 3). The tip of Meckel diverticulum was perforated. The diameter of perforation site was measured about 1 cm and identified the small bowel adhesions with pus patches around the perforated area (Fig. 4). The perforated Meckel diverticulum was successfully removed by diverticulectomy and the specimen was sent to pathology for biopsy (Fig. 5).

After surgery, the child had a very uneventful hospital course and was discharged on postoperative day 5th day.

Meckel diverticulum is one of the most common congenital malformations of the gastrointestinal tract, occurring in 2% to 4% in genernal population. Only 4% of the Meckel diverticulums are symptomatic, while most cases are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally [4]. A high index of suspicion is necessary for prompt diagnosis and treatment. The diagnostic modalities including Meckel scan are effective in only 60% to 70% of all cases.

Most cases with Meckel diverticulum are asymptomatic (56%-77.5%) and present a diagnostic challenge. Only about 17% to 40% of cases are symptomatic, and the most common presentation is rectal bleeding (43%-80%), intussusception, intestinal obstruction (23%-42%), diverticulitis, and peritonitis (14%-24%) [5].

During the total life time, the complication rate of Meckel diverticulum is 4%, with a male-to-female ratio ranging from 1.8:1 to 3:1 [6]. Yamaguchi et al. [7] reported 14 cases of 600 patients; and the 287 symptomatic patients showed the following complication rates: obstruction, 36.5%; intussusception which often presents as obstruction, 13.7%; inflammation or diverticulitis and perforation, 12.7% and 7.3%, respectively; hemorrhage, 11.8%; neoplasm, 3.2%; and fistula, 1.7%. The current case demonstrated a very rare complication of Meckel diverticulum.

Shalaby et al. [8] reported about complication of Meckel diverticulum and operative mean age. The clinical data of 33 children admitted with rectal bleeding and/or recurrent abdominal pain with no identifiable cause were reviewed over a period of 8 years. There were 23 boys and 10 girls with a mean age of 5.12±2.00 years (range, 3-12 years). And a 3-year-old patient was youngest.

It is well known as fact that if a Meckel diverticulum have no complication, any operation is useless. But when complication is occur and symptoms are arise, the patient have to be process operation. Among the complications, the intestinal obstruction is most common. And second is diverticulitis and third is bleeding. But perforation is very rare [9].

Several cases of perforation of Meckel diverticulum have been reported in neonate. In Korea, a 5-day-old neonatal case has been reported [3]. However, only one case among infants has been reported worldwide. Türkmen et al. [10] reported sudden death of unknown cause in a 15-month-old boy shortly after he was admitted to the hospital. Autopsy examination revealed a cream-brown, greenish, foul-smelling fluid filled abdomen and perfation of Meckel diverticulum. So perforation of Meckel diverticulum in infant period is very rare cases. And it is very hard to diagnosis before life threatening condition. It is difficult to predict and diagnose the site of perforation prior to exploration, although duodenal and ileal perforation can be distinguished by observing the nature of the abdominal aspirates. If aspirated materials looks more bilious, it indicates duodenal perforation. In contrast, if aspirated materials look more feculent, it suggests ileal perforation.

There are various etiologies that lead to perforation of Meckel diverticulum. Firstly, progression of diverticulitis can cause perforation. Ulceration of adjacent ileal mucosa secondary to acid produced by ectopic gastric mucosa can also cause perforation. Furthermore, ingested foreign bodies such as fish or chicken bones and bay leaf can cause perforation. The features of either localized or generalized peritonitis on perofration of Meckel diverticulum are similar to perforation of other hollow viscera. It is managed by initial resuscitation and antibiotics followed by prompt diverticulectomy or segmental resection along with peritoneal irrigation.

Over the last several years, there has been an ongoing discussion on whether diverticulectomy should be performed as part of proper management of asymptomatic Meckel diverticulum. Soltero and Bill [6] reported that the lifetime complication risk of Meckel diverticulum is 4.2% and decreases with age, reaching 0% at 76 years of age. In contrast, Shalaby et al. [8] reported that the incidence of complications requiring surgery was 6.4%, with no trend related to age; the mortality rate of these patients was 1.5%, with 7% morbidity, while incidental removal had 1% mortality and 2% morbidity. Based on these results, they concluded that diverticulectomy is warranted.

In conclusion, we reported a rare case of perforation of Meckel diverticulum in an infant that was a life threatening condition.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Gastrointestinal ultrasonographic images show normal range of appendix intact (diameter 0.5 cm) (A) and intact ileocecal valve (B).

References

1. Park JJ, Wolff BG, Tollefson MK, Walsh EE, Larson DR. Meckel diverticulum: the Mayo Clinic experience with 1476 patients (1950-2002). Ann Surg. 2005; 241:529–533.

2. Martin JP, Connor PD, Charles K. Meckel's diverticulum. Am Fam Physician. 2000; 61:1037–1042. 1044

3. Lee SI, Huh YS, Kwun KB. A case of perforated Meckel's diverticulum in a 5-day-old neonate. J Korean Surg Soc. 1989; 36:817–821.

4. Arnold JF, Pellicane JV. Meckel's diverticulum: a ten-year experience. Am Surg. 1997; 63:354–355.

5. St-Vil D, Brandt ML, Panic S, Bensoussan AL, Blanchard H. Meckel's diverticulum in children: a 20-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 1991; 26:1289–1292.

6. Soltero MJ, Bill AH. The natural history of Meckel's diverticulum and its relation to incidental removal. A study of 202 cases of diseased Meckel's diverticulum found in King County, Washington, over a fifteen year period. Am J Surg. 1976; 132:168–173.

7. Yamaguchi M, Takeuchi S, Awazu S. Meckel's diverticulum. Investigation of 600 patients in Japanese literature. Am J Surg. 1978; 136:247–249.

8. Shalaby RY, Soliman SM, Fawy M, Samaha A. Laparoscopic management of Meckel's diverticulum in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:562–567.

9. Kim TH, Choi KH. Incidence of Meckel's diverticulum. J Korean Surg Soc. 2001; 60:636–639.

10. Türkmen N, Eren B, Gündoğmuş UN. Uncommon presentation of Meckel's diverticulum in young age. Maedica (Buchar). 2013; 8:40–42.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download