Abstract

The muscle trapezius shows considerable morphological diversity. Variations include an anomalous origin and complete or partial absence of the muscle. The present study reported, a hitherto undocumented complete bilateral absence of the cervical part of trapezius. Based on its peculiar origin and insertion, it was named dorsoscapularis triangularis. The embryological, phylogenetic and molecular basis of the anomaly was elucidated. Failure of cranial migration of the trapezius component of the branchial musculature anlage to gain attachment on the occipital bone, cervical spinous processes, ligamentum nuchae between 11 mm and 16 mm stage of the embryo, resulted in this anomaly. A surgeon operating on the head and neck region or a radiologist analyzing a magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical region would find the knowledge of this morphological variation of trapezius useful in making clinical decisions.

Trapezius, a flat triangular muscle, which forms a diamond shape with the muscle of the opposite side, helps suspend the pectoral girdle from the axial skeleton. On either side, the muscle takes origin from the medial third of the superior nuchal line, external occipital protruberance, ligamentum nuchae, and apices of the spinous processes and their supraspinous ligaments from C7 to T12. The superior fibres are attached to the the posterior border of the lateral thirds of the clavicle, the middle fibres to the medial acromial margin and superior lip of the crest of the scapular spine; and the inferior fibres pass into an aponeurosis which glides over a smooth triangular surface at the medial end of the scapular spine and is attached to a tubercle at the lateral apex [1].

The present study reports a case of dorsoscapularis triangularis, a rare variation of the muscle trapezius. There was a bilateral absence of the superior part of the muscle with no associated neurovascular anomalies. The trapezius forms a crucial landmark forming the boundary of the posterior triangle and it is commonly used in myocutaneous flaps for repairing major head and neck defects [2], the knowledge of such a variation should prove useful for radiologists analysing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as well as for the surgeons operating the Head and Neck region.

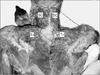

During routine dissection of the upper limb and back in a 54-year-old male cadaver, a hitherto unknown variation of the trapezius was discovered. The part of the muscle taking origin from the superior nuchal line, external occipital protuberance and the cervical spinous processes was deficient and the clavicular attachment was absent. The origin of the trapezius extended from the fifth cervical to the 10th thoracic vertebral spinous processes (Fig. 1). An aponeurosis attached the muscle to the fifth cervical to the third thoracic spinous processes bilaterally. The muscle was inserted into the medial acromial margin, the superior lip of the crest of scapular spine and to the tubercle at the lateral apex of the triangular area at the medial end of the scapular spine. The muscle was innervated from its deep aspect by spinal accessory nerve and received its blood supply from branches of the subclavian artery.

The part of splenius capitis, which lies under the trapezius, was seen under the deep cervical fascia. It took origin from the mastoid process and the area under the whole length of the superior nuchal line and was inserted into the spinous processes of the lower four cervical vertebrae and to the lower part of the ligamentum nuchae. The fibres of the two sides interlaced in the midline in a fibrous raphe (Fig. 1). The triangular aponeurosis of trapezius in the region of cervical spinous processes covered the lower part of the muscle.

There were no signs of trauma or past surgical procedures. No other neurovascular or muscular variations were observed (Fig. 2).

A myriad of anomalies of the muscle trapezius have been reported to occur sporadically or in association with congenital syndromes. These include, the clavicular attachment blending with the sternocleidomastoid, the vertebral attachment ending as high as the eighth thoracic vertebra and absent occipital attachment. The cervical and dorsal parts may be occasionally separate [1]. Unilateral or bilateral; complete or partial absence of the muscle has been reported by various authors [34].

A thorough search of the existing literature did not yield any documented cases of a complete bilateral absence of the cervical part of the muscle. In the present case, the muscle was in the form of a right angle triangle with the origin starting at the fifth cervical vertebra and ending at the tenth thoracic vertebra. Such a low anomalous origin has not been reported till date.

The muscle formed a right angled triangle with the hypotenuse stretching between the spine of scapula and the tenth thoracic vertebra. Together the muscle of the two sides formed an isosceles triangle rather than a classical trapezium. As this hitherto undocumented triangular muscle was limited to the dorsal aspect of scapula, it was given the name: dorsoscapularis triangularis.

The absence of trapezius may be a part of syndromes like Poland's syndrome and Klippel-Feil syndrome. These were ruled out due to an absence of associated features like thoracic wall or hand anomalies (Poland's syndrome) [5] or a shortened neck with ear anomalies (Klippel-Feil syndrome) [6].

Congenital absence of skeletal muscles is rare, the incidence ranging from 0.3% to 1.9% births [7]. Inflammatory, vascular, neuropathic or myopathic insults during early embryogenesis could account for the absence of cervical part of trapezius.

The trapezius develops from the branchial musculature first appearing in a 7 mm embryo, ventral to the two caudal occipital and two anterior cervical myotomes (Fig. 3). This anlage starts separating into a ventral sternocleidomastoid and dorsal trapezius starting in an embryo 9 mm in length. In an 11 mm embryo, the trapezial portion extends till about the sixth cervical nerve. At this stage the muscle is not attached to the shoulder girdle. The muscle is separated from a more dorsally lying myotomic mass by the thick deep cervical fascia (Fig. 4). In a 16 mm embryo, the muscle gains attachment to the spine of the scapula and adjoining part of clavicle. Cranially, it extends towards the ligamentum nuchae, yet it does not reach the occipital cartilage. Only in an embryo of 20 mm length, the trapezius acquire its adult extent [8]. The present findings could be explained by a failure of cranial migration of the trapezial component to gain attachment on the cervical spinous processes, ligamentum nuchae and the occipital bone between 11 mm and 16 mm stage of the embryo (Fig. 5).

In the primates Lemur catta, Strepsirrhines, Galago and Tarsius, the trapezius has no occipital origin. In Lemur catta, the cervical portion of trapezius is entirely aponeurotic. It arises from ligamentum nuchae until about the middle of the neck and from T1–T9 spines and gets inserted into the scapular spine and acromion but not on the clavicle [9]. In the present case, trapezius took origin from the spinous processes of fifth cervical until the 10th thoracic vertebrae. The calvicular attachment of the muscle was absent. In accordance with the dictum: ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, the arrest of the embryologenesis of trapezius at a stage where it resembles primates' trapezius, could account for the above findings.

HOX D4 and somitic mesoderm contribute to the development of sternocleidomastoid and trapezius, where they are connected to the skeletal elements only by posterior otic neural-crest derived connective tissue. Since HOX D4 and somites contribute muscle cells to branchial neck muscles, these myoblasts seem to associate with neural-crest derived muscular connective tissue [10]. A mutation of the HOX D4 could result in such an anomaly.

During life, synergistic muscles must have compensated for the partial absence of trapezius. The more extensive origin and higher shift of the insertion of splenius capitis probably contributed to stabilization and movements of the neck.

Trapezius muscle myocutaneous flaps are commonly used for reconstruction of head and neck defects either as island or pedicled flaps [2]. An extended vertical lower trapezius island myocutaneous flap is used during a salvage surgery for advanced oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas [11]. Surgeons encountering peroperatively such a variation may have to alter their approach for a myocutaneous flap.

The anterior border of the trapezius forms the boundary of the posterior triangle, the absence of the cervical part would lead to the distortion of the normal anatomy which the surgeon has to be vigilant about during any surgery in this region including modified radical neck dissection for lymphatic metastasis. The spinal accessory nerve is an important structure that the surgeon aims to protect during this procedure [12]. A sound knowledge of anatomical variations of trapezius is necessary for any surgeon operating on the head and neck region. It should also be borne in mind by the radiologists while interpreting an MRI for lesions seen in the posterior triangle.

The present study hopes to create awareness in the minds of surgeons and radiologists alike, about the variations of the trapezius muscle, which will help them to plan surgeries or to interpret imaging data. It would also be of interest to anatomists and anthropologists, who are ever intrigued and excited about morphological variations.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Dissection of the back and neck showing absence of cervical part of trapezius. Dotted black line depicting the normal extent of the cervical part of trapezius. SC, splenius capitis; Tz, trapezius.

Fig. 2

Muscles undercover of trapezius seen after reflecting it laterally. LS, levator scapulae; Rh, rhomboides; Tz, trapezius.

Fig. 3

Diagrammatic representation of a 7 mm embryo showing the Anlage for sternocleidomastoid and trapezius lying ventral to the cranial myotomes. Modified from Keibel and Mall (1910) [8]. An, branchial muscle anlage for sternocleidomastoid and trapezius.

Fig. 4

Diagrammatic representation of an 11 mm embryo showing the splitting of the anlage into ventral sternocleidomastoid and dorsal trapezius. Modified from Keibel and Mall (1910) [8]. Sc, scapula; SCM, sternocleidomastoid; Tz, trapezius.

Fig. 5

Diagrammatic representation of a 16 mm embryo showing failure of cranial migration of the trapezial component to gain attachment on the cervical spinous processes, ligamentum nuchae and the occipital bone. Modified from Keibel and Mall (1910) [8]. De, deltoid; SC, splenius capitis; SCM, sternocleidomastoid; Tz, trapezius.

References

1. Standring S. Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice. 40th ed. Madrid: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone;2008.

2. Colletti G, Tewfik K, Bardazzi A, Allevi F, Chiapasco M, Mandalà M, Rabbiosi D. Regional flaps in head and neck reconstruction: a reappraisal. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015; 73:571.e1–571.e10.

3. Allouh M, Mohamed A, Mhanni A. Complete unilateral absence of trapezius muscle. McGill J Med. 2004; 8:31–33.

4. Horan FT, Bonafede RP. Bilateral absence of the trapezius and sternal head of the pectoralis major muscles: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977; 59:133.

5. Yiyit N, Işıtmangil T, Öksüz S. Clinical analysis of 113 patients with Poland syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015; 99:999–1004.

6. Miyamoto RT, Yune HY, Rosevear WH. Klippel-Feil syndrome and associated ear deformities. Am J Otol. 1983; 5:113–119.

7. Takahashi H, Umeda M, Sakakibara A, Shigeta T, Minamikawa T, Shibuya Y, Komori T. Absence of the sternocleidomastoid muscle in a patient that underwent neck dissection for squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Kobe J Med Sci. 2014; 59:E167–E171.

8. Keibel F, Mall FP. Manual of human embryology. Philadelphia, PA: J.B Lippincott Company;1910.

9. Diogo R, Wood BA. Comparative anatomy and phylogeny of primate muscles and human evolution. New York: CRC Press;2012.

10. Mehta V, Arora J, Kumar A, Nayar AK, Ioh HK, Gupta V, Suri RK, Rath G. Bipartite clavicular attachment of the sternocleidomastoid muscle: a case report. Anat Cell Biol. 2012; 45:66–69.

11. Chen WL, Li J, Yang Z, Huang Z, Wang J, Zhang B. Extended vertical lower trapezius island myocutaneous flap in reconstruction of oral and maxillofacial defects after salvage surgery for recurrent oral carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:205–211.

12. Umeda M, Shigeta T, Takahashi H, Oguni A, Kataoka T, Minamikawa T, Shibuya Y, Komori T. Shoulder mobility after spinal accessory nerve-sparing modified radical neck dissection in oral cancer patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010; 109:820–824.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download