Abstract

In 40-50% of all polyhydramnios cases, no apparent cause can be identified and are classified as idiopathic. More than ten percent of babies with idiopathic polyhydramnios revealed certain anomalies after a course of clinical suffering. Congenital myotonic dystrophy (CMD) is one of them. Myotonic dystrophy is the most common form of neuromuscular disorder in adults. CMD is an autosomal dominantly inherited disease, inherited mostly from the mother. Severely affected CMD infants exhibit very critical respiratory failure, and the prognosis is unfavorable in up to 30% of cases. Polyhydramnios coexists with almost all CMD fetuses. A provisional diagnosis of CMD in a pregnancy complicated with polyhydramnios and maternal grip myotonia before birth may be helpful to the neonatology team for planning a thorough and prepared care for newborn patients. We report two cases to inform neonatologists as well as obstetricians that a provisional diagnosis of CMD can be made in a pregnancy complicated with polyhydramnios in a mother with grip myotonia or myotonic dystrophy.

Polyhydramnios occurs in 1-2% of all pregnancies.1 It reflects many maternal and fetal conditions, including maternal diabetes mellitus, placental tumors, fetal abnormalities, and fetal anemia. Although the causes of polyhydramnios can be found in more than 50% of cases, causes are unidentified in others, and these are referred to as idiopathic polyhydramnios. More than ten percent of babies with initial assessment of idiopathic polyhydramnios revealed anomalies on postnatal follow-up.1 Polyhydramnios correlates with fetal morbidity and a two-to five-fold increase in the risk of perinatal mortality.2 Severe polyhydramnios is associated with poor fetal and neonatal outcomes, such as a prematurity and a fatality. It is a requirement for physicians to figure out the cause of polyhydramnios and be prepared to manage the problems after birth.

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) is the most common neuromuscular disease in adults. The dystrophia myotonica protein kinase (DMPK) gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 19q13. The mechanism of the disease is an expansion of the tri-nucleotide repetition Cytosine-Thymine-Guanine (CTG) in the non-coding region of the DMPK gene at 19q13.3.3 CTG repeat is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern and is almost always enlarged when inherited.4 Mildly affected, symptom-free women can have a 50% chance of transmitting the disease to their offspring.5 Myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2), which is rarer than DM1, is a progressive multisystemic disorder with several clinical manifestations and pathogenic mechanisms in common with DM1. DM2 is caused by CCTG unstable repeats in ZNF9 gene, and is histopathologically different from DM1.6 DM2 tends to have a milder phenotype with later onset of symptoms. Only DM1 is associated with severe symptoms in the newborn period, a form known as congenital myotonic dystrophy (CMD).

CMD is an autosomal dominant disease with hypotonia and myotonia. The incidence is one per 3,500 to 16,000 individuals approximately.7 However, population based incidence studies were not reported. Severely affected infants are floppy at birth and have respiratory difficulty due to diaphragmatic hypoplasia. At least 20% of affected newborns die during the neonatal period, and those who survive have significant learning disability. The birth of an affected infant to a previously undiagnosed mother results in the family being screened for the disease. In an old study of idiopathic polyhydramnios, up to 10% of fetuses were revealed to have CMD.8 The aim of this report is to inform neonatologists as well as obstetricians that one should consider the possibility of neonates having CMD, when the mother is a known myotonic dystrophy patient or is suffering from a mild form of grip myotonia, and the pregnancy is complicated with polyhydramnios.

A 37-year-old woman was admitted due to polyhydramnios on the antenatal ultrasonography. As the mother was known to have myotonic dystrophy, and the pregnancy was complicated with polyhydramnios (amniotic fluid index, AFI 37.7), we speculated that the fetus could have CMD. Her past obstetric history was significant for a spontaneous abortion and a stillbirth after having one healthy child. On hospital day 3, a newborn male weighing 1,620 g was delivered by a Cesarean section at 30+6 weeks of gestation with Apgar scores of 3 at 1 min, and 6 at 5 mins. Initial creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level was 190 U/L. The newborn was severely edematous and floppy at birth and had talipes. In spite of aggressive mechanical ventilation, he died at 30 hours of life as a result of respiratory failure. We made a clinical diagnosis of CMD. The DMPK gene analysis was not performed.

A 26-year-old woman was admitted due to preterm labor. She has no specific past history or family history. Fetal ultrasonography on admission showed polyhydramnios (AFI 33.6) and bilateral clubfoot. On the next day, a newborn female weighing 1,760 g was delivered via vaginal delivery at 32+2 weeks of gestation with Apgar scores of 6 at 1 min, and 7 at 5 mins. The CPK level was 113 U/L. The newborn was suffering from respiratory difficulty, floppiness with weak activity, weak crying, inverted V-shaped (tented) upper lip and talipes. Mechanical ventilation was required. When the mother first visited the NICU, she was confirmed positive for grip myotonia. Consequently, we made a clinical diagnosis of CMD. The baby was on a mechanical ventilation for 17 days. Brain ultrasonography revealed mild ventriculomegaly. A mutation analysis of DMPK gene was performed, which showed about a thousand repetitions of CTG triplets (Fig. 1). The mother was also checked for a mutation of DMPK gene, and the CTG expansion was found to be more than four hundred. She was also confirmed as myotonic dystrophy.

Polyhydramnios is a challenge to both obstetricians and neonatologists because of its association with many known maternal and fetal conditions. Polyhydramnios with undefined causes before delivery presents even greater challenges. There is a two- to five-fold increase in perinatal mortality risk in a pregnancy complicated with idiopathic polyhydramnios.2 Some babies born of mothers with idiopathic polyhydramnios suffer from polyuria, loss of intravascular volume, and, if not properly managed, shock. More than 10% of babies with idiopathic polyhydramnios have revealed certain anomalies after a course of clinical suffering,1 and CMD is one of them.

As in case 1, severely affected CMD infants are affected with very severe respiratory failure from diaphragmatic hypoplasia and/or pulmonary hypoplasia and, resulting in fatality. Because of the maternal history of myotonic dystrophy and pregnancy complicated with polyhydramnios, we can suspect the baby to have CMD. Unfortunately, the DMPK gene analysis was not performed. However, we do not think the baby remains undiagnosed.

Since CMD is potentially fatal, severe, and chronic in nature – with events such as unexpectedly complicating course of respiratory problem, difficulties in feeding, and developmental delays leading to the poor prognosis of CMD9 - the suspicion and/or confirmation of the disease before birth is required. Since up to 30% of CMD patients have unfavorable prognosis,10 it is essential to anticipate respiratory complications in the baby and prepare a systematic approach for resuscitation, and provide counsel to the parents before birth to better manage the baby after birth.11

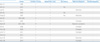

In the first description of CMD in 1960, the pregnancy and delivery history of patients was not a major concern.12 A more specific description of CMD in 1993 reported that the most characteristic symptoms during the pregnancy of CMD babies were polyhydramnios and reduced fetal movement.13 We found more than 10 reports on CMD in Korea through the literature review. Among 23 reported cases, polyhydramnios was coexistent in more than half (Table 1). No mother was known to have myotonic dystrophy before birth of the babies in these reports. However, we suspected that three cases of recurrent polyhydramnios in prior reports were suggestive of the mothers having myotonic dystrophy.

With respect to maternal myotonic dystrophy, the rate of polyhydramnios occurrence was reported to be high, the presence was thought to indicate that the fetus was abnormal.3 In a study of pregnancies complicated by myotonic dystrophy, polyhydramnios occurred in 17% of pregnancies and was exclusively seen in mothers with congenitally affected fetuses.14 Theoretically, half of the pregnancies in mothers with myotonic dystrophy would result in CMD. In other studies with pregnancies in mothers with myotonic dystrophy, 40 to 60% of pregnancies were confirmed as CMD,1516 and the best correlated finding was polyhydramnios (100%).16 Talipes and borderline ventriculomegaly were found in 26.6% and 13.3% of CMD fetuses on a sonography, respectively.16 A tent-shaped mouth was also reported as a typical feature of CMD in utero.17

CMD is transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern. Even though paternal transmission of CMD was reported,18 transmissions are mostly maternal in origin. Mildly affected myotonic dystrophy patients remained asymptomatic. However, myotonia was often aggravated during pregnancy.10 To discriminate whether the fetus has CMD in case of polyhydramnios, the disease condition of the mother is crucial. For the screening of myotonic dystrophy in previously asymptomatic mothers, checking for grip myotonia is useful, like in the second case of this report. To check for grip myotonia, mothers are asked to firmly grip and release. If there is a several seconds' delay until full relaxation, grip myotonia is present.16 The presence of maternal grip myotonia is helpful in differentiating CMD from other hypotonias with polyhydramnios.

The causes of neonatal hypotonia can be classified either as central or peripheral in origin. The most common central cause of hypotonia was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, which has a different clinical history from CMD. The most common peripheral cause of hypotonia was CMD.1920 Therefore, when the pregnancy is complicated with polyhydramnios and possibly fetal hypotonia, a test for grip myotonia would be useful to discover fetal CMD before birth.

It seems reasonable to make a molecular diagnosis of CMD in utero since this condition is associated with high neonatal mortality and lifelong disability. However, CTG repeat size in amniocytes and villi was poorly correlated with other fetal tissues,15 and amniocentesis and/or chorionic villi sampling have their own risks of complications.4 Decisions to terminate the pregnancy by antenatal diagnosis also impose ethical problems. We would rather recommend making a provisional diagnosis of CMD in pregnancies complicated with polyhydramnios in mothers with grip myotonia. In this point of view, we would suggest that the neonatologists should be encouraged to have a chance for a prenatal interview and/or physical examination of mother who is suffering from polyhydramnios. This anticipation would be much helpful to the neonatology team as it can help in planning a thorough and prepared care for the newborn patient.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1PCR-Southern analysis of DMPK on 19q13.2-q13.3. The arrow showed this newborn's DNA. The DNA amplified to more than 3,000bps, and it means CTG triplet expansion is more than a thousand. This finding is consistent with Congenital Myotonic Dystrophy. |

Table 1

Reported Cases in the Korean Literature

(1) J Korean Child Neurol Soc 1998;5:356-60, (2) Korean J Obstet Gynecol 2001;44:2302-6, (3) J Korean Soc Neonatol 2002;9:204-10, (4) Korean J Obstet Gynecol 2003;46:658-62, (5) Korean J Perinatol 2005;16:250-4, (6) Korean J Pediatr 2006;49:1158-66, (7) J Korean Soc Neonatol 2006;13:194-8, (8) Korean J Pediatr 2007;50:868-74, (9) J Korean Neurol Assoc 2008;26:383-6, (10) J Genet Med 2009;6:166-9, (11) Korean J Anesthesiol 2012;63:169-72, (12) J Korean Soc Clin Neurophysiol 2012;14:80-2, (13) J Korean Med Sci 2012;27:1269-72, (14) J Korean Med Sci 2014;29:879-83.

References

1. Boito S, Crovetto F, Ischia B, Crippa BL, Fabietti I, Bedeschi MF, et al. Prenatal ultrasound factors and genetic disorders in pregnancies complicated by polyhydramnios. Prenat Diagn. 2016; 36:726–730.

2. Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Doherty DA, Lutgendorf MA, Magann MI, Morrison JC. A review of idiopathic hydramnios and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007; 62:795–802.

3. Webb D, Muir I, Faulkner J, Johnson G. Myotonia dystrophica: obstetric complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978; 132:265–270.

4. Khan ZA, Khan SA. Myotonic dystrophy and pregnancy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009; 59:717–719.

5. Ashizawa T, Dubel JR, Dunne PW, Dunne CJ, Fu YH, Pizzuti A, et al. Anticipation in myotonic dystrophy. II. Complex relationships between clinical findings and structure of the GCT repeat. Neurology. 1992; 42:1877–1883.

6. Vanacore N, Rastelli E, Antonini G, Bianchi ML, Botta A, Bucci E, et al. An Age-Standardized Prevalence Estimate and a Sex and Age Distribution of Myotonic Dystrophy Types 1 and 2 in the Rome Province, Italy. Neuroepidemiology. 2016; 46:191–197.

7. Prendergast P, Magalhaes S, Campbell C. Congenital myotonic dystrophy in a national registry. Paediatr Child Health. 2010; 15:514–518.

8. Esplin MS, Hallam S, Farrington PF, Nelson L, Byrne J, Ward K. Myotonic dystrophy is a significant cause of idiopathic polyhydramnios. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 179:974–977.

9. Turner C, Hilton-Jones D. The myotonic dystrophies: diagnosis and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010; 81:358–367.

10. Dufour P, Berard J, Vinatier D, Savary JB, Dubreucq S, Monnier JC, et al. Myotonic dystrophy and pregnancy. A report of two cases and a review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997; 72:159–164.

11. Textbook of neonatal resuscitation. 7th ed. Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics;2016.

13. Hageman AT, Gabreels FJ, Liem KD, Renkawek K, Boon JM. Congenital myotonic dystrophy; a report on thirteen cases and a review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 1993; 115:95–101.

14. Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Zerres K. Outcome in pregnancies complicated by myotonic dystrophy: a study of 31 patients and review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004; 114:44–53.

15. Geifman-Holtzman O, Fay K. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital myotonic dystrophy and counseling of the pregnant mother: case report and literature review. Am J Med Genet. 1998; 78:250–253.

16. Zaki M, Boyd PA, Impey L, Roberts A, Chamberlain P. Congenital myotonic dystrophy: prenatal ultrasound findings and pregnancy outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 29:284–288.

17. Mashiach R, Rimon E, Achiron R. Tent-shaped mouth as a presenting symptom of congenital myotonic dystrophy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 20:312–313.

18. Zeesman S, Carson N, Whelan DT. Paternal transmission of the congenital form of myotonic dystrophy type 1: a new case and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002; 107:222–226.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download