Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to show the radiologic features of various lesions appearing as skin thickening or enhancement under the breast MRI. And histopathologic results of the skin lesions were correlated. Radiologist must be familiar with normal appearance of the breast skin under the MRI and a wide variety of conditions may affect the skin of the breast.

As breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is being used more frequently to screening and diagnosis of breast malignancies, we often encounter various breast skin lesions appearing as skin thickening or enhancement. Although numerous studies have reported about the breast parenchymal lesions, the dermal lesions of the breast have largely been overlooked. The breast skin lesions may be incidental findings to be ignored, but sometimes the lesions are associated with breast cancer or other malignancies. Occasionally, the skin thickening or enhancement of the breast on MRI is the only finding to raise concern for tumor recurrence at the mastectomy site, treated or reconstructed breast of the breast cancer patient. In this article, we discuss the normal findings of the breast skin on MRI and demonstrate a spectrum of dermal lesions of the breast range from benign to malignant entities.

The MRI scans were acquired with the patient in the prone position in a 1.5T scanner (Achieva; Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) and a 3.0T scanner (Magnetom Verio; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a breast coil. The MR images with the Achieva scanner were performed using the following sequences: sagittal, fat-suppressed, and fast spin-echo T2-weighted imaging sequence (TR/TE 6000/100 ms, flip angle of 90°, 30 slices, field of view [FOV] of 320 mm, matrix 424 × 296, number of excitations [NEX] of 1, 4 mm slice thickness with 0.1 mm interslice gaps, and acquisition time of 2 min 56 sec) and precontrast and postcontrast dynamic axial T1-weighted three-dimensional, fat-suppressed, fat-spoiled gradient-echo sequence (TR/TE 6.9/3.4, flip angle of 12°, 2.0 mm slice thickness with no gap, acquisition time of 1 min 31 sec) obtained before and at 0, 91, 182, 273, 364, and 455 sec after a rapid bolus injection of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) (Magnevist; Schering, Berlin, Germany) at 0.1 mmol/kg of body weight. The MR images with the Verio scanner were acquired using the following sequences: axial, turbo spin-echo T2-weighted imaging sequence (TR/TE 4530/93 ms, flip angle 80°, 34 slices with FOV 320 mm, matrix 576 × 403, 1 NEX, 4 mm slice thickness, acquisition time 2 min 28 sec) and pre- and postcontrast axial T1-weighted flash three-dimensional, VIBE sequence (TR/TE 4.4/1.7, flip angle 10°, 1.2 mm slice thickness with no gap, acquisition time 60 sec) obtained before and at 7, 67, 127, 187, 247, and 367 sec after a bolus injection of 0.1 mmol/kg Gd-DPTA.

In the conventional breast MRI including T2-weighted imaging sequence, precontrast and postcontrast dynamic axial T1-weighted sequences; we have to focus on the early enhanced T1 weighted image for detecting skin lesion and skin enhancement. In the supine MRI (chest of abdomen) as well as prone, skin lesion and skin enhancement could be detected.

The skin is composed of three layers: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis, or the subcutaneous fat layer (Fig. 1a). The epidermis is indistinguishable as a separate layer from the dermis at imaging. The epidermis and dermis appear as a symmetric and smooth, with a thickness of 0.5-2 mm at MRI, except caudally where it may be slightly thicker due to its usual dependency. Although some investigators have noted that the normal skin may not enhance at MRI, the others have found that it is usually demonstrates mild thin enhancement (12) (Fig. 1b).

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare, highly aggressive form of primary breast cancer that comprises 1-6% of all the cases of breast cancer. Clinically, IBC is characterized by the rapid onset of swelling and enlargement of the breast. The overlying skin remains intact, but there is erythema that is often combined with a "peau d'orange" texture, local tenderness, induration and warmth. IBC is classified as T4d lesion; it is associated with a poor prognosis because of approximately 20% of cases of IBC already having metastasis at the time of presentation. Pathologically, any subtype of primary breast cancer may be present, but the dermal lymphatic vessels must be involved (345). MRI is the imaging tool of choice in evaluating patients with potential IBC. The MRI features of IBC are skin thickening and a reticular/dendritic pattern of parenchymal enhancement (Fig. 2). MRI showed significantly higher accuracy for depiction and delineation of a primary breast parenchymal abnormalities and skin thickening in IBC patients compared with conventional mammography and ultrasonography. Moreover, MRI is essential in treatment planning, as it supplies information of disease extent. Skin changes, global skin thickening or nodular or irregular skin foci, may occur in a different quadrant than that in which the underlying parenchymal mass is located (567). The majority of the kinetic pattern of the pathologic proven malignant skin lesions showed delayed persistent enhancement, delayed washout pattern, and delayed plateau pattern, respectively. IBC and locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) remain two of the most aggressive forms breast cancer. Sometimes, it is difficult to identifying IBC and differentiating it from LABC in breast imaging. Despite being often grouped together, identifying IBC is very important, because IBC is a distinct clinical and pathological entity that requires distinct treatment from LABC. Girardi et al. (8) found a variety of statistically significant differences between the appearance of IBC and LABC at MRI. Skin changes (thickening, edema and enhancement) related to neoplastic involvement of the dermal lymphatics are suggestive of IBC than LABC (8910).

Superficial or locally advanced breast cancers can directly extend to the breast skin, usually causing skin thickening, focal (Fig. 3) or diffuse (Fig. 4), or multiple nodules (Fig. 5), even ulceration (Fig. 6) or fungating masses. In some cases, breast cancer with skin involvement by the indirect process, such as ipsilateral satellite skin nodules are seen on breast MRI (Fig. 7).

However, some superficial breast malignancies without direct skin invasion may cause edema or inflammation of the overlying skin, which is secondary change due to lymphatics or venous obstruction. The superficial malignancies, arising at ductal epithelium located just deep to the dermis, can be mistaken for malignant dermal involvement (1). In these cases, radiologist must be careful to avoid the misdiagnosis, but it is, often almost impossible. According to the current edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system, non-inflammatory breast cancer with direct extension to the skin are classified as T4b lesions, the most advanced locoregional extent (stage IIIB). Undoubtedly, these findings were defined as grave prognostic factor for a long time (1112). Several systematic studies have reported widely differing prognostic and therapeutic implications in to these non-inflammatory breast cancer and they proposed the revision of TNM staging that would classify these tumors based on their tumor size and lymph node status (1314151617).

Locoregional tumor recurrence may occur in the breast skin rarely. Recurrence may involve the skin by means of (a) invasion along the Cooper ligaments to the retinacula cutis attachment points at the dermis, or (b) involvement of the lymphatic channels draining to the skin (18). Early detection of skin recurrence is crucial, because it has been shown to be a predictor for distant metastases, which is a poorer prognosis than other local recurrence. However, detection of early recurrence is difficult, because of background of treatment changes due to radiotherapy and/or surgery. The skin is difficult area to assess using mammography or ultrasonography, MRI may be the problem solving tool for early detection of skin recurrence (19202122). On MRI, focal and nodular enhancement or increased skin thickening are correlated with histology demonstrating tumor recurrence (Fig. 8), whereas linear, diffuse, or smooth enhancement is correlated with benign postoperative change (21). Most recurrences will occur in the quadrant of the original tumor, so focused clinical breast examination and imaging studies may provide earlier detection (23). When the findings are vague, pathologic confirmation should not be hesitated.

Other malignant diseases can involve breast skin are angiosarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, melanoma and non-breast metastasis. Angiosarcomas are rare tumors of endovascular origin and they are classified into primary and secondary groups. Radiation induced secondary angiosarcomas can affect breast cancer patient with history of radiotherapy following breast conserving surgery and their average latency period reported as 6-12.5 years. They are difficult to diagnose due to their rarity, benign appearance and difficulty in differentiation from radiation induced skin change (242526). On MRI, cutaneous angiosarcomas are shown as small enhancing skin lesions at irradiated site with varying kinetic patterns (27). Cutaneous metastasis is a relatively uncommon manifestation of breast malignancy. Frequent primary sites of cutaneous metastasis are originated from the lung, gastrointestinal, ovary and skin (melanomas). Lymphoma and leukemia also involve the breast skin (28). Most of the times it occurs late in the course of the disease, so the prognosis for patients with cutaneous metastasis is usually poor. On MRI, the cutaneous metastatic lesions are usually focal or diffuse skin thickening, but they often mimicking inflammatory cancer (29) (Fig. 9). Primary or secondary lymphoma may involve breast skin. T-cell lymphoma, especially subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell or peripheral T-cell lymphoma, preferentially infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue (3031). On MRI, irregular masses with a rim or heterogeneous enhancement in the subcutis may be present (32) (Figs. 10,11).

Mastitis may occur in the puerperal or non-puerperal state. The most common causative organisms are staphylococcus and streptococcus, although tuberculosis may sometimes be encountered. Clinically, these patients may present with a focal area of tenderness with associated erythema and induration (3334). Ultrasonography is very useful for evaluation inflammatory parenchymal and cutaneous change and detecting breast abscess, complications of mastitis. However, if there is no association of mastitis and abscess with pregnancy and lactation, or if there is inadequate resolution after antibiotic therapy, then ultrasonography-guided biopsy or MRI are useful to exclude inflammatory breast cancer. Acute mastitis shows overlapping imaging features with IBC (Figs. 12,13,14), however the combination of multiple dynamic and morphological criteria seems to have the potential for a differential diagnosis. The main location of acute mastitis was subareolar, whereas IBC are more often located centrally or dorsally. The following morphologic criteria, punched-out sign, T2-hypointensity of masses, blooming sign, infiltration of pectoralis major muscles, perifocal, prepectoral and intramuscular edema, is more often seen in IBC. The definition of punched-out sign, a reliable indicator for the lymphatic infiltration of the skin, is accentuated nodular enhancement of the skin occurring at fast in time, compared to surrounding normal skin (35). Nevertheless, if any diagnosis doubt exits, a histological verification is mandatory.

Chronic granulomatous mastitis is a very rare inflammatory disease of an unknown origin that can clinically and radiologically mimic infectious and malignant breast condition. This disease usually affects women of childbearing age or those with a history of oral contraceptive use. It is pathologically characterized by chronic granulomatous inflammation of the lobules without caseous necrosis or evidence of microorganism. The diagnosis of granulomatous mastitis is based on excluding other granulomatous reactions such as tuberculosis (363738). Although there are no radiologic pathognomonic findings specific to this entity, there is a few MRI characteristics can help differential diagnosis. MRI findings of peripherally located ring-enhancing lesions can suggest of chronic granulomatous mastitis (Fig. 15). The condition may respond to antibiotics and oral steroids, and surgery is also performed for disease control. The prognosis is often good, but local recurrence has been reported (39).

Breast edema can be caused by a variety of pathologic processes of benign or malignant disease, as a result of a tumor in the dermal lymphatics of the breast, lymphatic congestion caused by the breast, lymphatic drainage obstruction, or by systemic condition such as congestive heart failure and nephritis syndrome. Bilateral breast edema has mostly been reported in systemic problems. Mechanical problems such as obstruction due to lymph node enlargement (Fig. 16), subclavian vein occlusion, and especially arteriovenous hemodialysis complications, may cause unilateral breast edema (40).

As recently oncologic and plastic surgeries, core needle biopsies, mammotome procedure of the breast have increased, radiologist must cultivate an understanding of expected post-treatment imaging features and be able to differentiate these changes from suspicious breast lesions.

Recognizing the normal chronological imaging findings after breast conserving treatment with followed radiation change is important to minimize unnecessary recall or diagnostic work up. Focal skin thickening and/or enhancement, edema is commonly seen in the immediate postoperative period, but these imaging findings should be resolved with time (Fig. 17). These changes should not be interpreted as recurrent or remnant tumor involvement. After followed radiation therapy, diffuse or patchy skin enhancement and thickening, which correspond with radiation field, becomes more commonly (Fig. 18). The skin thickening seen on MRI of the breast correlated with histological thickening of the dermis by increased connective tissue and edema, and these changes presumably reflect radiation-induced inflammation and fibrosis (21). Skin enhancement is most often seen during the first 18 months after treatment, in some patients, residual faint enhancement may persist for several years (41). High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation is a rarely performed application for treatment of early-stage breast cancer, not a conventional treatment regimen for breast cancer. HIFU induces a temperature elevation and the tissue can be thermally destroyed by sonic energy (42), so one of its complications is skin burn (Fig. 19). These days, diverse reconstructive and cosmetic breast surgeries have evolved, familiarity with their imaging characteristics is essential for radiologic interpretation (Fig. 20). When equipped with an understanding of breast surgery techniques and their expected complications, radiologists may be able to differentiate normal postoperative changes from malignancy at imaging of these patients.

Fat necrosis may result from accidental trauma is a relatively common benign entity in the breast. The inciting event on breast is often related to blunt trauma, such as motor vehicle crash and seat-belt injury. Fat necrosis has various appearances on MRI, typically benign to worrisome for malignancy; depend on the intensity of the inflammatory process. Because of its superficial location, some cases are associated with adjacent skin change, for instance bruise, edema, tethering or dimpling (43). These changes are shown as skin thickening and enhancement on breast MRI (Fig. 21). Eliciting the history of a traumatic event can be helpful in making the diagnosis of fat necrosis. Sometimes, fat necrosis may mimic breast cancer or concomitant breast cancer may be present, radiologist should be careful not to jump to conclusion.

The most common dermal masses encountered by breast imagers are dermal cysts, specifically epidermal inclusion cysts and sebaceous cysts. Other common masses involving the hypodermal lesions are including lipoma, angiolipoma, hemangioma and thromobosed vessel (44). In addition, other dermatologic lesions could cause nonspecific skin thickening. Little study has been devoted to the appearance of these superficial lesions, because of they are not indication of MRI, but encountered at breast MRI incidentally. According to one of the few reports on the MRI appearance of dermal cysts, epidermal cyst, which is most common epithelial cyst of the breast, appear as a well-defined subcutaneous mass and isointense at T1-weighted imaging and heterogeneously hyperintense at T2-weighted imaging (45). These lesions may have peripheral rim enhancement that may even appear as solid internal progressive enhancement on postcontrast T1-weighted images, a finding that may be secondary to volume averaging. Recognizing the typical extension of the mass into the dermis can help make the correct diagnosis and usually localization of the lesions is more accurate at ultrasonography than MRI (1).

In conclusion, many conditions can involve the skin on breast MRI. Unfortunately, the skin lesions on breast MRI have been ignored because of the decreased spatial resolution of MRI. But, MRI finding preceded the patient's clinical evaluation and was the first change for detection of the abnormality. The radiologist must be familiar with various spectrum of cutaneous lesion. A high index of suspicion, careful patient evaluation and adequate biopsy tissue for pathologic diagnosis is mandatory for accurate diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Normal breast. (a) Diagram of skin. (b) On axial subtraction breast MRI obtained after administration of gadolinium contrast material shows normal skin with mild and smooth enhancement.

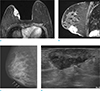

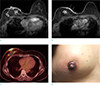

Fig. 2

A 46-year-old woman with inflammatory caner involving left breast underwent breast MRI and PET-CT. (a) On axial breast MRI, diffuse heterogeneous nonmass enhancement and diffuse skin thickening with enhancement at left breast is seen. There is irregular enhancement of the pectoralis muscle suggesting invasion. The kinetic curve of skin shows persistent enhancement pattern. (b) On PET-CT, huge mass with intense FDG uptake is seen in left breast (SUVmax 10.1) and diffuse and mild FDG uptake is also seen on breast skin (SUVmax 4.3).

Fig. 3

A 39-year-old woman, underwent excision of florid ductal hyperplasia, 9 years before. There was thickening at the skin layer of excision site, and the punch biopsy revealed invasive ductal cancer. (a, b) On axial and sagittal breast MRI, irregular enhancing mass with direct skin invasion is seen. Focal skin thickening with enhancement is clearly seen. (c, d) On right mediolateral view of mammography and US, mass with direct skin invasion (arrows) is also seen.

Fig. 4

A 50-year-old woman with invasive ductal cancer involving left breast underwent breast MRI and PET-CT. (a, b) On axial breast MRI, irregular and huge infiltrative enhancing mass with direct skin invasion and enhancement is seen. Nipple and areolar complex is also involved. Skin thickening and enhancement is diffuse, over third of breast skin is involved. (c) On PET-CT image, the mass with FDG uptake is seen (SUVmax 18.4) and diffuse and mild FDG uptake is seen on overlying skin.

Fig. 5

A 62-year-old woman with mixed invasive ductal and mucinous cancer involving left breast underwent breast MRI and PET-CT. (a) On axial breast MRI, multiple conglomerated masses at upper outer quadrant of left breast and multiple skin nodules are clearly seen. Kinetic curve of skin nodules shows fast rise and delayed plateau pattern. (b) On PET-CT image, the mass with FDG uptake (SUVmax 8.8) is seen at left breast. And a few skin nodules with mild FDG uptake (arrows) is also seen.

Fig. 6

A 41-year-old woman, who was detected breast cancer because of palpable mass with skin ulceration. (a, b) On axial breast MRI, irregular enhancing mass with direct skin invasion and enhancement is seen. And defect of overlying skin is clearly seen, which is considered T4b stage.

Fig. 7

A 70-year-old woman with invasive lobular cancer involving right breast underwent breast MRI. (a, b) On axial breast MRI, segmental clumped nonmass enhancement is seen at upper portion of right breast. Diffuse skin thickening and enhancement is seen in right breast. (c) On clinical photography, multiple ipsilateral satellite skin nodules are seen, which is correlated with MRI detected skin thickening. The patient underwent punch biopsy of skin nodules, the pathologic result was poorly differentiated cancer originated breast cancer.

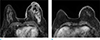

Fig. 8

A 46-year-old woman who underwent wide excision of right breast 13 months before due to invasive ductal cancer. She complained newly developed skin nodules and underwent punch biopsy for them. Pathology revealed metastatic cancer. (a, b) On axial breast MRI, multifocal irregular enhancing masses (open arrows) surrounding postoperative hematoma in right breast, suggesting recurrent tumor. The masses at anterior portion of the hematoma directly invades of skin. And multiple skin nodules with diffuse skin thickening (arrows) are clearly seen. (c) On PET-CT, the skin thickening and skin nodules show FDG uptake (SUVmax 15.7). (d) On clinical photograph of right breast, focal skin thickening and erythema around the nipple is correlated with direct skin invasion of recurrent tumor. And several skin nodules at mid inner portion of breast are correlated with nodular skin thickening on breast MRI.

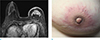

Fig. 9

A 56-year-old woman, who underwent chemotherapy due to advanced gastric cancer, complained of swelling and erythema of left breast. She underwent punch biopsy of the skin lesion and pathologic result was metastatic cancer. (a) On axial breast MRI, irregular heterogeneous enhancing mass with skin thickening and enhancement on left breast is evident. These findings mimic inflammatory breast cancer. (b) On clinical photography of left breast, breast swelling and erythema around the nipple is correlated with skin invasion of metastatic tumor.

Fig. 10

A 14-year-old girl visited the out-patient clinic for evaluation of pain and palpable mass on her left breast. She underwent core needle biopsy and pathologic result was primary cutaneous extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma. (a, b) On axial and sagittal breast MRI, irregular heterogeneous enhancing mass with skin thickening and enhancement on left breast is evident. (c) Maximal intensity projection image shows mass with skin invasion clearly. (d) On US image, irregular hyperechoic mass with indistinct margin at left breast was evident.

Fig. 11

A 53-year-old woman visited outpatient clinic for evaluation of palpable masses on both breasts. She underwent core needle biopsy and pathologic result was primary breast lymphoma, diffuse large B cell lymphoma. (a) On axial breast MRI, huge irregular enhancing masses at both breasts with diffuse enhancing skin thickening are evident. (b) On US image of left breast, diffuse skin thickening and huge irregular heterogeneous echoic mass are also seen.

Fig. 12

A 40-year-old woman visited outpatient clinic because of pain, erythema and edema on her left breast. She underwent core needle biopsy for left breast, pathologic result was acute and chronic mastitis with microabscess formation and vague granulomas with multinucleated giant cells. (a) On axial breast MRI, diffuse skin thickening with enhancement is seen on her left breast. Diffuse heterogeneous enhancement with trabecular thickening on left breast consistent with acute mastitis. (b) On US image, insinuating irregular hypoechoic lesion with increased echogenicity of subcutaneous fat layer and overlying diffuse skin thickening are seen.

Fig. 13

A 54-year-old woman, who underwent mammoplasty with saline bag, visited outpatient clinic because of pain, erythema and pus drainage on her left breast. (a, b) On axial and sagittal breast MRI, focal skin thickening with fistula tract (arrows) is seen on her left breast. (c) On clinical photography, erythema with two, fistula tracts are seen on her left breast, which is consistent with MRI finding.

Fig. 14

A 33-year-old woman visited outpatient clinic because of pain and swelling after autologous fat injection on her breasts. She underwent debridement and curettage of left breast. (a, b) On axial and sagittal breast MRI, ill-defined soft tissue infiltration with enhancement along the retromammary space at left breast is seen, which is suggestive of inflammation with abscess formation. Diffuse skin thickening with enhancement and dark signal void of air is clearly seen.

Fig. 15

A 41-year-old woman, who suffered from recurrent erythema and painful swelling on her breast, visited outpatient clinic. She underwent breast core needle biopsy and MRI. Pathologic result was chronic lobular granulomatous mastitis. (a, b) On axial breast MRI, clustered ring pattern of nonmass enhancement at left breast peripheral portion is seen with diffuse skin thickening and enhancement (arrow). The findings are consistent with microabscess. (c) On sagittal breast MRI, mild skin retraction abutting to microabscess is clearly seen (arrow).

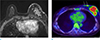

Fig. 16

A 56-year-old woman, who was diagnosed ovarian cancer with metastatic cancer in left axilla, underwent breast MRI. (a, b) On axial T2 and T1 weighted breast MRI, diffuse skin and trabecular thickening of left breast are clearly seen. (c) On axial MRI for axilla, multiple conglomerated metastatic lymph nodes (arrow) are seen. The findings are consistent with obstructive edema due to blocked lymphatics or vein occlusion.

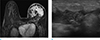

Fig. 17

A 42-year-old woman underwent wide excision of left breast due to invasive ductal cancer. She underwent breast MRI annually after the operation. (a) On axial breast MRI after operation, parenchymal defect with architectural distortion at left breast is seen. Focal skin thickening and enhancement (arrows) is also evident, which is consistent with postoperative and postradiation change. (b) After four years from operation, the skin thickening and enhancement are regressed.

Fig. 18

A 58-year-old woman, who was diagnosed breast cancer 2 years before but refused any treatment at that time, visits outpatient clinic for control growing mass at breast. She underwent combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy on her right breast. During the radiation therapy, she suffered from radiation ulcer. (a) On axial breast MRI nonmass enhancement at outer portion of right breast and diffuse skin thickening with enhancement is seen. (b, c) On axial and sagittal breast MRI, skin defect (arrows) on diffusely thickened breast skin thickening is clearly seen, which is radiation ulcer.

Fig. 19

A 59-year-old woman, who underwent HIFU for treatment of left breast cancer, visited our hospital for evaluation of treatment response. Her skin on breast was burned during the High-intensity focused ultrasound. (a) On axial breast MRI, focal skin thickening with enhancement on her left breast is seen (arrows). (b) On US image, skin thickening overlying irregular hypoechoic lesion (ablated mass) is clearly seen.

Fig. 20

A 47-year-old woman underwent modified radical mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction with contralateral free DIEP flap coverage due to breast cancer. (a, b) On axial breast MRI, diffuse skin thickening and fat necrosis on reconstructed left breast is evident. (c) On US image, diffuse skin thickening and fat necrosis in reconstructed breast is also seen clearly.

Fig. 21

A 71-year-old woman, who underwent passenger's traffic accident, visited outpatient clinic for evaluation of palpable mass on her left breast. She underwent core needle biopsy for left breast, pathologic result was hematoma formation and fat necrosis due to seat belt injury. (a-c) On axial and sagittal breast MRI, nonenhancing mass at left breast upper portion is seen, suggesting hematoma with fat necrosis. Focal skin thickening with retraction (arrows) and minimal trabecular thickening are also evident. (d) On axial T2 image, high signal intensity hematoma and edema are seen in left breast.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a fund for breast MRI study group from Korean Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

References

1. Kalli S, Freer PE, Rafferty EA. Lesions of the skin and superficial tissue at breast MR imaging. Radiographics. 2010; 30:1891–1913.

2. Morris EA, Liberman L. Breast MRI: diagnosis and intervention. 2005; New York, NY: Springer.

3. Dershaw DD, Moore MP, Liberman L, Deutch BM. Inflammatory breast carcinoma: mammographic findings. Radiology. 1994; 190:831–834.

4. Ellis DL, Teitelbaum SL. Inflammatory carcinoma of the breast. A pathologic definition. Cancer. 1974; 33:1045–1047.

5. Yang WT, Le-Petross HT, Macapinlac H, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer: PET/CT, MRI, mammography, and sonography findings. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008; 109:417–426.

6. Le-Petross HT, Cristofanilli M, Carkaci S, et al. MRI features of inflammatory breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 197:W769–W776.

7. Le-Petross CH, Bidaut L, Yang WT. Evolving role of imaging modalities in inflammatory breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2008; 35:51–63.

8. Girardi V, Carbognin G, Camera L, et al. Inflammatory breast carcinoma and locally advanced breast carcinoma: characterisation with MR imaging. Radiol Med. 2011; 116:71–83.

9. Anderson WF, Chu KC, Chang S. Inflammatory breast carcinoma and noninflammatory locally advanced breast carcinoma: distinct clinicopathologic entities? J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21:2254–2259.

10. Renz DM, Baltzer PA, Bottcher J, et al. Inflammatory breast carcinoma in magnetic resonance imaging: a comparison with locally advanced breast cancer. Acad Radiol. 2008; 15:209–221.

11. Haagensen CD, Stout AP. Carcinoma of the breast. II-Criteria of operability. Ann Surg. 1943; 859–870.

12. Haagensen CD, Bodian C. A personal experience with Halsted's radical mastectomy. Ann Surg. 1984; 199:143–150.

13. Gueth U, Wight E, Schoetzau A, et al. Non-inflammatory skin involvement in breast cancer, histologically proven but without the clinical and histological T4 category features. J Surg Oncol. 2007; 95:291–297.

14. Guth U, Singer G, Langer I, et al. T4 category revision enhances the accuracy and significance of stage III breast cancer. Cancer. 2006; 106:2569–2575.

15. Guth U, Wight E, Schotzau A, et al. A new approach in breast cancer with non-inflammatory skin involvement. Acta Oncol. 2006; 45:576–583.

16. Guth U, Wight E, Singer G. Breast cancer with noninflammatory skin involvement: new data revise the traditional image of a "classical" clinicopathologic entity. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2006; 95:1829–1835.

17. Wieland AW, Louwman MW, Voogd AC, van Beek MW, Vreugdenhil G, Roumen RM. Determinants of prognosis in breast cancer patients with tumor involvement of the skin (pT4b). Breast J. 2004; 10:123–128.

18. Stavros AT, Rapp CL, Parker SH. Breast ultrasound. 2004; Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

19. Kamby C, Andersen J, Ejlertsen B, et al. Pattern of spread and progression in relation to the characteristics of the primary tumour in human breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 1991; 30:301–308.

20. Orel SG, Fowble BL, Solin LJ, Schultz DJ, Conant EF, Troupin RH. Breast cancer recurrence after lumpectomy and radiation therapy for early-stage disease: prognostic significance of detection method. Radiology. 1993; 188:189–194.

21. Ralleigh G, Walker AE, Hall-Craggs MA, Lakhani SR, Saunders C. MR imaging of the skin and nipple of the breast: differentiation between tumour recurrence and post-treatment change. Eur Radiol. 2001; 11:1651–1658.

22. Voogd AC, van Tienhoven G, Peterse HL, et al. Local recurrence after breast conservation therapy for early stage breast carcinoma: detection, treatment, and outcome in 266 patients. Dutch Study Group on Local Recurrence after Breast Conservation (BORST). Cancer. 1999; 85:437–446.

23. Vaughan A, Dietz JR, Aft R, et al. Scientific Presentation Award. Patterns of local breast cancer recurrence after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2007; 194:438–443.

24. Bolin DJ, Lukas GM. Low-grade dermal angiosarcoma of the breast following radiotherapy. Am Surg. 1996; 62:668–672.

25. Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994; 102:757–763.

26. Hunter TB, Martin PC, Dietzen CD, Tyler LT. Angiosarcoma of the breast. Two case reports and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1985; 56:2099–2106.

27. Sanders LM, Groves AC, Schaefer S. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the breast on MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 187:W143–W146.

28. Nouri K. Skin cancer. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical;2008.

29. Nebesio CL, Goulet RJ, Jr , Helft PR, Billings SD. Metastatic esophageal carcinoma masquerading as inflammatory breast carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2007; 46:303–305.

30. Sy AN, Lam TP, Khoo US. Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma appearing as a breast mass: a difficult and challenging case appearing at an unusual site. J Ultrasound Med. 2005; 24:1453–1460.

31. Uematsu T, Kasami M. 3T-MRI, elastography, digital mammography, and FDG-PET CT findings of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) of the breast. Jpn J Radiol. 2012; 30:766–771.

32. Shim E, Song SE, Seo BK, Kim YS, Son GS. Lymphoma affecting the breast: a pictorial review of multimodal imaging findings. J Breast Cancer. 2013; 16:254–265.

33. Crowe DJ, Helvie MA, Wilson TE. Breast infection. Mammographic and sonographic findings with clinical correlation. Invest Radiol. 1995; 30:582–587.

34. Ulitzsch D, Nyman MK, Carlson RA. Breast abscess in lactating women: US-guided treatment. Radiology. 2004; 232:904–909.

35. Renz DM, Baltzer PA, Bottcher J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of inflammatory breast carcinoma and acute mastitis. A comparative study. Eur Radiol. 2008; 18:2370–2380.

36. Fletcher A, Magrath IM, Riddell RH, Talbot IC. Granulomatous mastitis: a report of seven cases. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35:941–945.

37. Han BK, Choe YH, Park JM, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: mammographic and sonographic appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999; 173:317–320.

38. Van Ongeval C, Schraepen T, Van Steen A, Baert AL, Moerman P. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Eur Radiol. 1997; 7:1010–1012.

39. Gautier N, Lalonde L, Tran-Thanh D, et al. Chronic granulomatous mastitis: imaging, pathology and management. Eur J Radiol. 2013; 82:e165–e175.

40. Kwak JY, Kim EK, Chung SY, et al. Unilateral breast edema: spectrum of etiologies and imaging appearances. Yonsei Med J. 2005; 46:1–7.

41. Heywang-Kobrunner SH, Schlegel A, Beck R, et al. Contrast-enhanced MRI of the breast after limited surgery and radiation therapy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993; 17:891–900.

42. Wu F, Wang ZB, Chen WZ, et al. Extracorporeal high intensity focused ultrasound ablation in the treatment of 1038 patients with solid carcinomas in China: an overview. Ultrason Sonochem. 2004; 11:149–154.

43. Taboada JL, Stephens TW, Krishnamurthy S, Brandt KR, Whitman GJ. The many faces of fat necrosis in the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009; 192:815–825.

44. Giess CS, Raza S, Birdwell RL. Distinguishing breast skin lesions from superficial breast parenchymal lesions: diagnostic criteria, imaging characteristics, and pitfalls. Radiographics. 2011; 31:1959–1972.

45. Iglesias A, Arias M, Santiago P, Rodriguez M, Manas J, Saborido C. Benign breast lesions that simulate malignancy: magnetic resonance imaging with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2007; 36:66–82.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download