Abstract

Background

The prevalence of obesity is increasing in Korea, including rural areas. We examined the changes in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS), defined by revised National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) or International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria, in a rural area of Korea during the past 6 years.

Methods

A total of 1,119 subjects (424 men and 695 women) aged ≥ 30 years were initially recruited in 1997. Baseline clinical data and various laboratory values were obtained. Six years later, we performed a follow-up study in 814 subjects (316 men and 498 women) of which 558 were original participants and 256 subjects were new. The prevalence of MetS was assessed by the criteria of NCEP or IDF.

Results

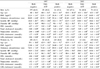

The prevalence of central obesity and impaired fasting glucose increased in both sexes during the period between 1997 and 2003. The prevalence of MetS according to the IDF criteria also increased. In men, the age-adjusted prevalence of MetS was 10.9% in 1997 and 23.3% in 2003. In women, it was 42.2% in 1997 and 43.4% in 2003. However, the prevalence of MetS according to the NCEP criteria increased only in men.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Changes in prevalence of the metabolic syndrome by age group, sex, and criteriaby modified NCEP ATP III (ATP) and IDF.

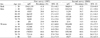

Table 1

Anthropometric and biochemical characteristics in subjects with surveyed in 1997 and 2003 by sex.

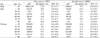

Table 2

Characteristics of anthropometric and biochemical parameters of 558 follow up subjects by sex and year of examination

References

1. Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors. JAMA. 2001. 289:76–79.

2. Ford ES, Giles WH. Trends in waist circumference among US adults. Obes Res. 2003. 11:1223–1231.

3. Palaniappan L, Wang Y, Hanley AJ, Fortmann SP, Haffner SM, Wagenknecht L. Predictors of the incident metabolic syndrome in adults: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care. 2004. 27:788–793.

4. Lorenzo C, Martinez-Larrad MT, Gabriel R, Williams K, Gomez-Gerique JA, Stern MP, Haffner SM. Central adiposity determines prevalence differences of the metabolic syndrome. Obes Res. 2003. 11:1480–1487.

5. Maison P, Hales CN, Day NE, Wareham NJ. Do different dimensions of the metabolic syndrome change together over time? Evidence supporting obesity as the central feature. Diabetes Care. 2001. 24:1758–1763.

6. World Health Organization. Definition dacodmaic: part I. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. 1999.

7. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005. 112:2735–2752.

8. Einhorn D, Cobin RH, Ford E, Ganda OP, Handelsman Y, Hellman R, Jellinger PS, Kendall D, Krauss RM, Neufeld ND, Petak SM, Rodbard HW, Seibel JA, Smith DA, Wilson PW. American College of Endocrinology position statement on the insulin resistance syndrome. Endocr Pract. 2003. 9:237–252.

9. Balkau B, Charles MA. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1999. 16:442–443.

10. Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome--a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005. 366:1059–1062.

11. Simonson GD, Kendall DM. Diagnosis of insulin resistance and associated syndromes: the spectrum from the metabolic syndrome to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Coron Artery Dis. 2005. 16:465–472.

14. Kim ES, Han SM, Kim YI, Song KH, Kim MS, Kim WB, Park JY, Lee KU. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of metabolic syndrome in a rural population of South Korea. Diabet Med. 2004. 21:1141–1143.

15. Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Odell PM, Kannel WB. An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation. 1991. 83:356–362.

16. Lim S, Park KS, Lee HK, Cho SI. Changes in the characteristics of metabolic syndrome in Korea over the period 1998-2001 as determined by Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Diabetes Care. 2005. 28:1810–1812.

19. Lorenzo C, Williams K, Gonzalez-Villalpando C, Haffner SM. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome did not increase in Mexico City between 1990-1992 and 1997-1999 despite more central obesity. Diabetes Care. 2005. 28:2480–2485.

20. Mahaney MC, Blangero J, Comuzzie AG, VandeBerg JL, Stern MP, MacCluer JW. Plasma HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and adiposity. A quantitative genetic test of the conjoint trait hypothesis in the San Antonio Family Heart Study. Circulation. 1995. 92:3240–3248.

21. Rissanen P, Vahtera E, Krusius T, Uusitupa M, Rissanen A. Weight change and blood coagulability and fibrinolysis in healthy obese women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001. 25:212–218.

22. Coulston AM, Liu GC, Reaven GM. Plasma glucose, insulin and lipid responses to high-carbohydrate low-fat diets in normal humans. Metabolism. 1983. 32:52–56.

23. Yoon YS, Lee ES, Park C, Lee S, Oh SW. The new definition of metabolic syndrome by the international diabetes federation is less likely to identify metabolically abnormal but non-obese individuals than the definition by the revised national cholesterol education program: The Korea NHANES Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007. 31:528–534.

24. Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L, Morris RW. Metabolic syndrome vs Framingham Risk Score for prediction of coronary heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2005. 165:2644–2650.

25. Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsen B, Lahti K, Nissen M, Taskinen MR, Groop L. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001. 24:683–689.

26. McNeill AM, Rosamond WD, Girman CJ, Golden SH, Schmidt MI, East HE, Ballantyne CM, Heiss G. The metabolic syndrome and 11-year risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2005. 28:385–390.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download