Abstract

Background

Following the increase in the number of children with food allergies, support systems are now required for school lunches, but a large-scale factual investigation has not been carried out.

Objective

We evaluated the features of elimination diet due to food allergy and the support system in kindergartens and schools.

Methods

A prefecture-based questionnaire survey regarding measures for food allergies in school lunches of all kindergartens, public elementary schools, and public junior high schools (631 facilities) was conducted in Oita Prefecture, Japan.

Results

The recovery rate of the questionnaire was 99.5%, which included 106,008 students in total. A total of 1,562 children (1.5%) required elimination diets. The rate of children on elimination diets in kindergartens and elementary/junior high schools that required medical certification by a physician was 1.2% (324 among 27,761 children), which was significantly lower than the 1.8% of children (1,227 among 68,576 students) on elimination diets at the request of guardians without the need for medical certification (p < 0.0001). A total of 43.9% of the kindergartens and schools said that they would contact guardians if symptoms were observed after accidental ingestion, while a low 8.1% stated that they provided support to children themselves, including the administration of adrenaline auto-injectors.

Conclusion

Medical certification reduces the number of children requiring elimination diets, but it has not been adequately implemented. Furthermore, waiting to contact guardians after symptoms are observed may lead to the delayed treatment of anaphylaxis. Cooperation between physicians and teachers is desired to avoid the overdiagnosis and undertreatment of children with food allergies.

An increase in the number of children with food allergy and anaphylaxis [1] has been accompanied by an increase in occasions requiring emergency care at home, nursery, kindergarten, and school [23]. Urisu et al. [4] found that approximately 5%–10% of infants and 1%–2% of school children have food allergies in Japan. Ohtani et al. [5] noted that allergies to hen eggs were the most common food allergies in Japan; however, regarding the prognosis thereof, it has been determined that 30%, 59%, and 73% of children acquire tolerance by 3, 5, and 6 years of age, respectively. Therefore, the unnecessary prescription of long-term elimination diets must be avoided [6].

Although the rates of children with food allergies requiring elimination diets in schools have been previously reported [78910], a wide-scale factual investigation has not been carried out.

In this study, we conducted a questionnaire study directed at all public/private kindergartens, public elementary schools, and public junior high schools in Oita Prefecture, Japan, and determined the potential problems associated with school lunches for children with food allergies.

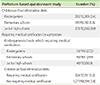

In 2011, upon acquiring informed consent from all 18 municipalities associated with the Board of Education and Private Kindergarten Association of Oita Prefecture, we sent out questionnaires to 631 kindergartens and schools, including all public/private kindergartens (134/63 kindergartens), all public elementary schools (302 schools), and all public junior high schools (132 schools), and requested that responses be return via facsimile. The questionnaire is described in Table 1. A chi-square test was used to determine the statistical significance, which was set at p < 0.05.

The recovery rate of the questionnaire was 99.5% (195 kindergartens, 301 elementary schools, and 132 junior high schools), which included 106,008 students overall.

As shown in Table 2, the questionnaires revealed that there were a total of 1,562 children (1.5%) with elimination diets, including 292 kindergarteners (2.4%), 997 elementary school students (1.6%), and 273 junior high school students (0.9%). Regarding the establishment of elimination diets in school lunches, “Medical certification by a physician is required” was selected by only 53 kindergartens (27.2%), 90 elementary schools (29.9%), and 40 junior high schools (30.3%).

The rate of children on elimination diets in kindergartens and elementary/junior high schools that required medical certification by a physician was 1.2% (324 among 27,761 children), which was significantly lower than the 1.8% of children (1,227 among 68,576 students) on elimination diets at the request of guardians without the need for medical certification (p < 0.0001).

As shown in Fig. 1, the number (rate) of institutions providing support via elimination diets or elimination and substitution diets in school lunches was 120 kindergartens (61.5%), 161 elementary schools (53.5%), and 55 junior high schools (41.7%).

As shown in Fig. 2, 73 kindergartens (37.4%), 135 elementary schools (45.9%), and 68 junior high schools (39.4%) said that they would contact guardians if symptoms were observed after accidental ingestion. However, the number (rate) providing tailored support, including the administration of adrenaline auto-injectors, was low, with responses reported in only 12 kindergartens (6.2%), 30 elementary schools (10.0%), and 9 junior high schools (6.8%). Surprisingly, 21 kindergartens (10.8%), 42 elementary schools (14.0%), and 40 junior high schools (30.3%) responded that they had no plans regarding how to deal with children with food allergies.

Oita Prefecture is located in the southern part of Japan. It has a population of 120 million people, and the annual number of births is 1 million, which is a 1/100 scale of Japan. The number of pediatric specialists in Oita Prefecture is also a 1/100 scale of Japan (150 of 16,410). This study was valuable for its high recovery rate (99.5%) of data on more than 100,000 children concerning measures for dealing with food allergies in school lunches.

A total of 1.5% children required elimination diets. The rate of children on elimination diets in kindergartens and elementary/junior high schools that required medical certification by a physician was 1.2%, which was significantly lower than the 1.8% of children on elimination diets at the request of guardians without the need for medical certification.

These results indicated that medical certification by a physician reduces the number of children requiring elimination diets. This may be due to the over-diagnosis of food allergies by children and parents. To both avoid long-term and excessive elimination [6] and correctly diagnose a food allergy, a medical certificate should be obtained. This is the first report that indicates the usefulness of medical certification for defining food allergies in school lunches. However, this measure has not been adequately implemented.

Regarding the support system available in the event of accidental ingestion, the majority of the schools said that they would contact guardians, regardless of the presence of symptoms. Few institutions said that they provided tailored support, including the administration of adrenaline auto-injectors. In children with severe food allergies, contacting the guardians only after symptoms are observed may lead to delayed treatment of anaphylaxis, where symptoms develop in a matter of minutes. In addition, some kindergartens and elementary/junior high schools stated that they had no plans for how to deal with food allergies; these institutions should establish measures against food allergies as soon as possible. Of note, these problems may not be specific to Japan. Indeed, Kim et al. [10] similarly described that over 80% of schools in Korea relied on self-care only, with no school-wide measures for students with food allergies in place.

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. First, these data were collected by Oita Prefecture, which is on a 1/100 scale for Japan. Our findings therefore do not represent the total picture of food allergies in Japan. Second, the credibility of this questionnaire, which was answered by school teachers, was not scientifically evaluated. Third, we did not investigate the quality of the medical certification. Fourth, we were unable to confirm why medical certification reduced the number of children requiring allergen elimination diets.

However, these results strongly suggest that cooperation between physicians and teachers is desirable to avoid the overdiagnosis and undertreatment of children with food allergies.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1The number and rate of support via elimination diets or elimination and substitution diets in school lunches. The number (rate) of institutions providing support via elimination diets or elimination and substitution diets in school lunches was 120 kindergartens (61.5%), 161 elementary schools (53.5%), and 55 junior high schools (41.7%). |

| Fig. 2The number and rate of support system in the event of accidental ingestion. Seventy-three kindergartens (37.4%), 135 elementary schools (45.9%), and 68 junior high schools (39.4%) said that they would contact guardians if symptoms were observed after accidental ingestion. However, the number (rate) providing tailored support, including the administration of adrenaline auto-injectors, was low, with responses reported in only 12 kindergartens (6.2%), 30 elementary schools (10.0%), and 9 junior high schools (6.8%). Surprisingly, 21 kindergartens (10.8%), 42 elementary schools (14.0%), and 40 junior high schools (30.3%) responded that they had no plans regarding how to deal with children with food allergies. |

References

1. Simons FE, Ebisawa M, Sanchez-Borges M, Thong BY, Worm M, Tanno LK, Lockey RF, El-Gamal YM, Brown SG, Park HS, Sheikh A. 2015 update of the evidence base: World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines. World Allergy Organ J. 2015; 8:32.

2. Ward CE, Greenhawt MJ. Treatment of allergic reactions and quality of life among caregivers of food-allergic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015; 114:312–318.e2.

3. Sandin A, Annus T, Björkstén B, Nilsson L, Riikjärv MA, van Hage-Hamsten M, Bråbäck L. Prevalence of self-reported food allergy and IgE antibodies to food allergens in Swedish and Estonian schoolchildren. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005; 59:399–403.

4. Urisu A, Ebisawa M, Ito K, Aihara Y, Ito S, Mayumi M, Kohno Y, Kondo N. Committee for Japanese Pediatric Guideline for Food Allergy. Japanese Society of Pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Japanese Society of Allergology. Japanese Guideline for Food Allergy 2014. Allergol Int. 2014; 63:399–419.

5. Ohtani K, Sato S, Syukuya A, Asaumi T, Ogura K, Koike Y, Iikura K, Yanagida N, Imai T, Ebisawa M. Natural history of immediate-type hen's egg allergy in Japanese children. Allergol Int. 2016; 65:153–157.

6. Meyer R, De Koker C, Dziubak R, Venter C, Dominguez-Ortega G, Cutts R, Yerlett N, Skrapak AK, Fox AT, Shah N. Malnutrition in children with food allergies in the UK. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014; 27:227–235.

7. Gandy LT, Yadrick MK, Boudreaux LJ, Smith ER. Serving children with special health care needs: nutrition services and employee training needs in the school lunch program. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991; 91:1585–1586.

8. Rhim GS, McMorris MS. School readiness for children with food allergies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001; 86:172–176.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download