This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

As an essential part of patient safety, pharmacovigilance is of worldwide interest and should expand its scope and focus on new emerging issues. South Korea has been making continuous efforts in the field of pharmacovigilance for the last 3 decades since voluntary adverse drug reaction (ADR) reporting system was first launched in 1988. Korea joined the World Health Organization Program for International Drug Monitoring in 1992, and the activities of Pharmacovigilance Research Network, Korean Society for Pharmacoepidemiology and Risk Management, and Regional Pharmacovigilance Center (RPVC) have contributed to the remarkable progress in the pharmacovigilance area and global status. RPVCs have played pivotal roles in establishment of pharmacovigilance system in Korea by monitoring voluntary ADR reports. RPVCs started with 3 hospitals in 2006 and have now expanded to 27 hospitals nationwide. The Korea Institute of Drug Safety & Risk Management was established in 2012 and in charge of operating the decentralized national pharmacovigilance system. The voluntary report of ADR, which is the basis of current pharmacovigilance system, has various limitations and an active surveillance system can be the overarching alternative. This change in pharmacovigilance paradigm is a global trend and Korea has excellent infrastructure such as broad distribution of electronic medical recording systems and a nationwide single healthcare insurance. As a result, the pharmacovigilance in Korea is now expected to progress to a new active surveillance system from traditional spontaneous reporting system.

Go to :

Keywords: Pharmacovigilance, Drug monitoring, Adverse drug reaction reporting systems, Drug-related side effects and adverse reactions, Korea

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacovigilance is defined as the science and activities related to the detection, assessment, understanding, and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug-related problems by the World Health Organization (WHO) [

1]. After the thalidomide disaster in the early 1960's, the need for postmarketing drug surveillance was raised. The Sixteenth World Health Assembly in 1963 suggested that adverse drug reaction (ADR) information must be shared, which led to the formation of the WHO Pilot Research Project for International Drug Monitoring in 1968 [

23]. This was the beginning of pharmacovigilance at the international level, which involved 10 countries: United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, Germany, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands, Sweden, Australia, and New Zealand [

4]. Currently, a total of 127 countries around the world are enrolled in the WHO Program for International Drug Monitoring and 29 countries are waiting for admission [

5].

Go to :

PAST: BUILDING A PHARMACOVIGILANCE BASIS IN KOREA

In 1988, the Korean government established a voluntary reporting system for ADR by designating 376 monitoring institutions in Korea (217 pharmacies and 159 hospitals). The number of monitoring institutions was expanded to 920 in the whole country in 1990 and the case report format was simplified from the previous version. An evaluation team was organized to monitor information about the ADR reaction obtained from WHO, United States, and Japan. Nine affiliated organizations, including the Korean Hospital Association, were appointed as cooperating institutions [

6]. Ever since the Republic of Korea join the WHO Program for International Drug Monitoring with the accumulated data and established system qualification in 1992, the number of ADR monitoring institutions in the nation continued to increase and reached 44,034 sites by 1996 [

7]. However, the actual number of reported adverse events was less than expected. The Ministry of Health and Welfare launched a pilot project to encourage voluntary ADR reports through the Internet while some hospitals and pharmaceutical companies were organized the ADR reporting system in 1999–2001. Despite all these efforts, voluntary ADR reporting has not been activated nationwide and has decreased with the end of the pilot project [

8].

In the 2000s, pharmaceutical companies and pharmacies were obligated to report ADRs. ADR reports in Korea have since grown in earnest with the Regional Pharmacovigilance Center (RPVC) pilot project from the Korean Food and Drug Administration (KFDA). The RPVCs, which play key roles in the Korean pharmacovigilance system, started in 3 university hospitals in 2006. The number of RPVCs gradually increased to 6 in 2007 and to 9 in 2008, which contributed to the rapid increase in ADR reports [

9]. From this period, the Korean RPVC council was organized by the professionals participating in RPVCs to build a network with which to share experiences and information.

The Korean Society for Pharmacoepidemiology and Risk Management was launched to form an academic basis for pharmacovigilance in 2007. Thus, the KFDA launched the Pharmacovigilance Research Network (PVNet) project in 2009, which continued to expand Korean pharmacovigilance competency by 2011 through various activities like international exchanges, clue information searching, intensive monitoring, standardization of adverse effect terms, and campaigning for the public awareness of pharmacovigilance [

10]. In the meantime, the number of RPVCs increased to 20 and covered almost the entire country.

After completing the PVNET activities, the government established the Korean Institute of Drug Safety & Risk Management (KIDS) in 2012 and commissioned the KIDS to continue RPVC operations and management [

11]. Since 2013, KIDS was authorized to manage pharmacovigilance by restricting government departments. As of 2017, the number of RPVCs is 27.

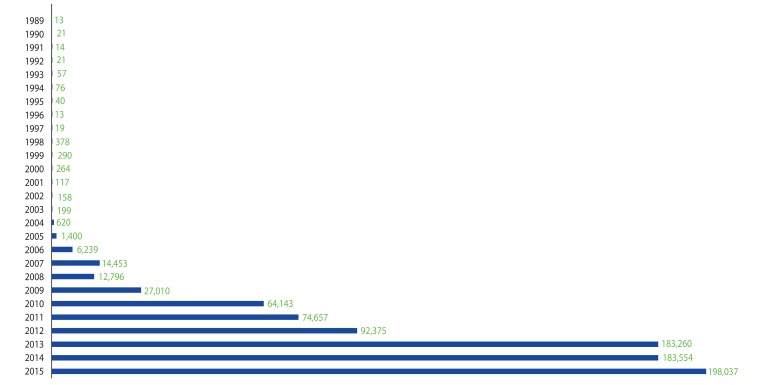

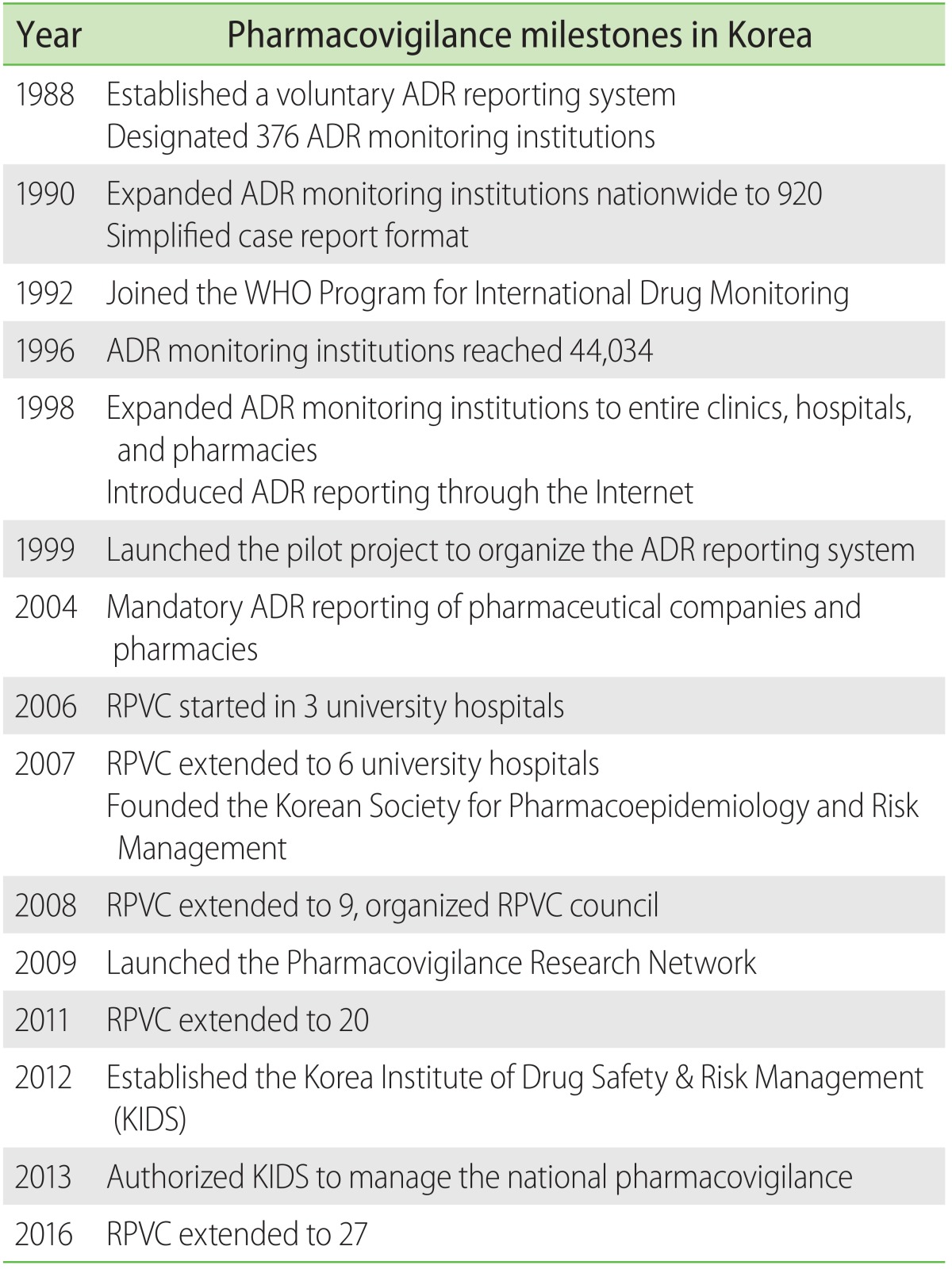

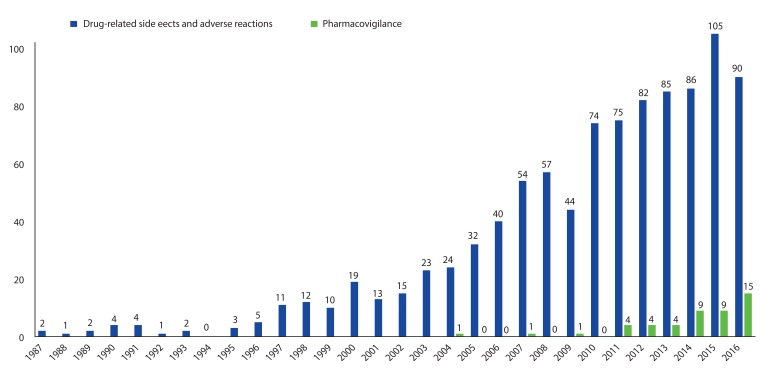

As such, the pharmacovigilance system of Korea has made continuous efforts and changes for development (

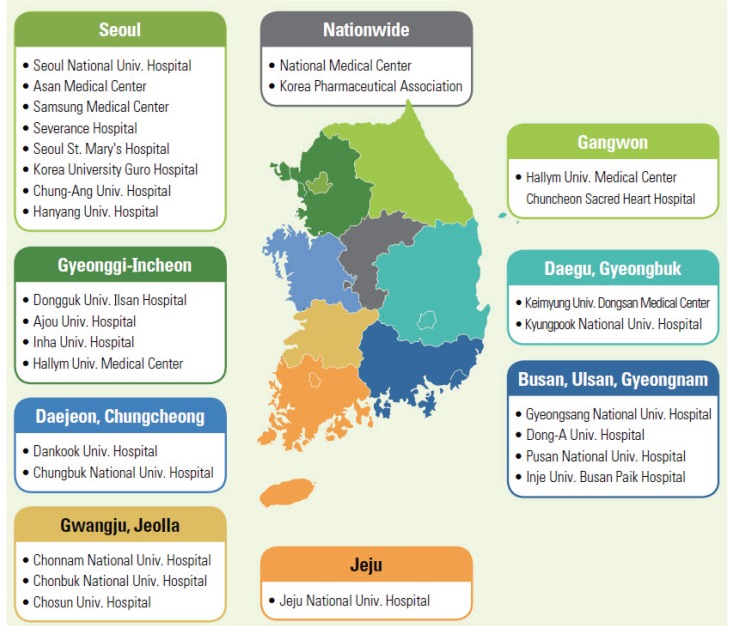

Table 1). The results were successful, as evidenced by increase in the number of voluntary reports at the times of major changes (

Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1Growth of spontaneous adverse event report in Korea.

|

Table 1

History of Korean pharmacovigilance system

Go to :

PRESENT: CURRENT PHARMACOVIGILANCE STATUS IN KOREA

Recently, the pharmacovigilance system has operated on a decentralized basis in Korea. KIDS acts as a center for RPVCs and collects data not only from RPVCs, but also from pharmaceutical companies. Each RPVC monitors adverse events reported from local clinics and pharmacies as well as the institutions themselves. They also perform intensive inspections on targeted populations and special medicinal products designated by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. KIDS offers consultations to reporters and consumers with emphasis on education and promotional campaigns to stimulate the pharmacovigilance activities.

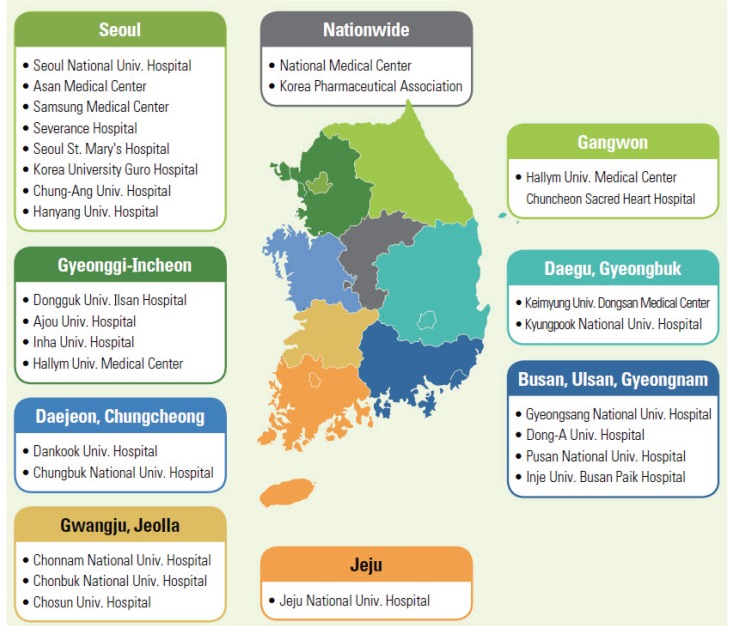

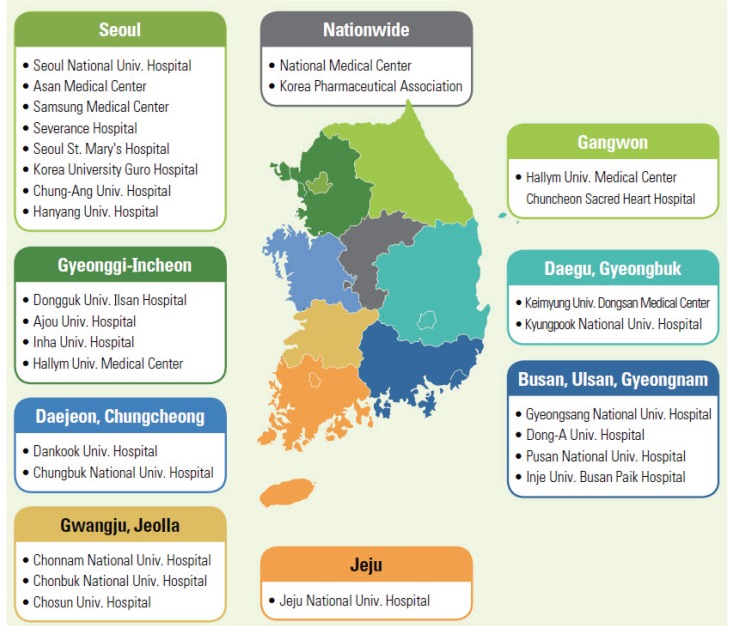

RPVCs have played pivotal roles in Korean pharmacovigilance based on the nationwide monitoring network and are currently composed of 25 regional university hospitals and 2 nationwide centers—the National Medical Center and the Korea Pharmaceutical Association—which run a nationwide network linking public medical institutions and local pharmacies (

Fig. 2) [

12]. The voluntary ADR reports from these RPVCs are the backbone of the Korean pharmacovigilance system.

| Fig. 2Pharmacovigilance Network in Korea: 27 Regional Pharmacovigilance Center [12].

|

In addition, some of the RPVCs conduct their own research and strategies for drug safety. In the case of RPVC at Seoul National University Hospital, programs for preventing adverse reactions to specific drugs such as contrast agents were established. They also run independent outpatient counseling center and engage in proactive drug safety activities beyond voluntary reporting. The results of these efforts are also linked to other RPVCs, contributing to the overall drug safety of Korea.

KIDS, which designates and manages RPVCs, collects and analyzes ADR data to search for clues in domestic pharmacovigilance. For international pharmacovigilance periodical reports are sent to the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring. KIDS also performs diverse activities to prevent ADR by developing the Drug Utilization Review criteria, providing drug safety education, and running a system for the relief of injury from ADR to provide compensation for victims and their families that suffered serious ADR [

13].

Due to improvements in the national system and the efforts of various medical personnel and practitioners, the Korean pharmacovigilance system has achieved remarkable progress in a short period of time. Along with this institutional development, interest in pharmacovigilance has also increased in the academic field. With the increasing number of publications on ADR, academic papers focused on pharmacovigilance have emerged in Korea in recent years (

Fig. 3).

| Fig. 3Growth of article publish on pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reactions in Korea.

|

However, many individual case safety reports lack detailed information. Therefore, KIDS has encouraged filling out the ADR report in detail and the data completion rate has steadily improved.

Go to :

FUTURE

Pharmacovigilance is essential for the future of medical practice due to the transition to an aging society, rise in prevalence of chronic diseases, ease of access to drugs, increase of multidrug use (polypharmacy), and expedited drug development. In 2016, the “Patient Safety Act” emphasized the importance of pharmacovigilance more than ever. Currently, the relief of injury from the ADR program will rapidly change the perception of ADR and the importance of establishing a safety system against ADRs. The scope of pharmacovigilance is being expanded due to all these changes. WHO has already announced that widening the horizon in the pharmacovigilance field is inevitable due to globalization, consumerism, explosion in free trade, communication across borders, and the increasing use of the Internet. For public safety, future pharmacovigilance should focus on new emerging issues, such as illegal sale of medicines online, self-medication practices, counterfeit and substandard medicines, and traditional or herbal medicines with potential for adverse effects. In addition, the boundary of pharmacovigilance must extend beyond medicines to herbal medicines, traditional medicines, alternative medicines, health functional foods, cosmetics, and medical devices [

1].

In the near future, the paradigm of pharmacovigilance will shift in Korea. As mentioned previously, the voluntary ADR reporting system has various limitations. The overarching alternative is an active surveillance system linked to large-scale, computerized data and this transition would be a global trend [

14]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and their cooperating center, the Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare Institute, developed an active pharmacovigilance system based on electronic medical records, named the Sentinel program [

15]. Unlike passive surveillance, Sentinel's active surveillance system enables the FDA to use existing electronic healthcare data in near real-time, a key advantage in quickly evaluating and understanding a safety issue. After a successful pilot study for 5 years, the Sentinel program expanded operations. Currently, the Sentinel program helps FDA's regulatory decision making and agency actions, such as recalls, withdrawals, label changes, safety, and risk communications [

16].

Korean academia and government have also researched and cooperated to develop a new active pharmacovigilance system in Korea. Recently, KFDA's research service has developed a common data model that can be applied for the electronic medical data of various hospitals [

17]. This common data model is a fundamental tool for establishing an active pharmacovigilance system like the Sentinel program from the United States. The next step is to build a competent cooperation center, such as the Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare Institute, to send queries to various data partners using the common data model and interpreting the results. Fortunately, Korea can build a pharmacovigilance system based on big data covering a large population due to the broad distribution of electronic medical recording systems and a nationwide single healthcare insurance system. Therefore, Korea is expected to make fast progress in a short period of time in the pharmacovigilance field.

These changes should occur without making a gap in the current pharmacovigilance system. The preceding voluntary ADR reporting system should be further activated by including not only tertiary hospitals, but also primary and secondary medical care facilities, pharmacies, pharmaceutical companies, other related professional groups, and consumer organizations. In addition to ADR reporting, RPVCs should maintain public safety functions like education and counseling on the safe use of medicines. Based on all these efforts to minimize the transition gap and to manage and prevent ADR more effectively, pharmacovigilance in Korea will develop a new active surveillance system in cooperation with already established spontaneous reporting systems.

Go to :

CONCLUSION

Korea has successfully installed a pharmacovigilance system covering the entire nation in a short period of time and is expected to show rapid development in the future.

Go to :