Abstract

Background

Autologous serum skin test (ASST) and autologous plasma skin test (APST) are simple methods to diagnose autoimmune chronic urticaria. However, the association data of ASST or APST with disease severity and long-term outcome are still unclear.

Objective

The results of ASST and APST might be used to predict urticaria symptom severity and long-term outcomes among chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) patients.

Methods

We evaluated the prevalence of reactive ASST and APST in 128 CSU patients. The patients were characterized by 4 groups: negative, ASST positive, APST positive, and both ASST and APST positive. We observed remission rate among the CSU patients during 2 years.

Results

Forty-four of 128 CSU patients (34%) had negative autologous skin test. The CSU patients with positive ASST, positive APST, and both positive ASST and APST were 47 (37%), 6 (5%), and 31 (24%), respectively. No significant difference was found between the groups according to urticaria severity score (USS) and dermatology life quality index (DLQI). Mean wheal diameter of ASST showed positive correlation with DLQI. Also, mean wheal diameter of APST showed positive correlation with USS and DLQI. Both the positive ASST and APST groups had a high proportion of 4-fold dose of H1-antihistamine than the positive ASST (p = 0.03) and negative groups (p = 0.0009). The rate of remission over 2 years in the negative, positive ASST, positive APST, and both positive ASST and APST groups were 81.1%, 62.3%, 60%, and 46.1%, respectively. The urticaria remission rate in patients in the negative group was significantly higher compared with both positive ASST and APST groups (odds ratio, 5.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.61–15.44; p = 0.006).

Chronic urticaria is common skin disease defined as spontaneous recurrent wheals or angioedma for at least 6 weeks. The disease is not fatal but is associated with psychiatric morbidity and reduced quality of life [12]. At any time, 0.5% to 1% of the population suffers from the disease and all age groups can be affected, so the peak incidence is between 20 to 40 years old [3]. The duration of disease is generally 1 to 5 years but may be a prolonged course more than 5 years in 14% of patients [4]. Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is the most common type of chronic urticaria, 70% to 90% of all cases [5]. More than half of CSU patients are thought to be caused by autoimmune mechanism [6]. An IgG autoantibody specific for the alpha subunit of the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) or low-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRII) or anti-IgE antibodies may be detected in autoimmune chronic urticaria patients [78]. That antibodies activated mast cells and basophils in the skin to release histamines [9]. Then histamines influence urticaria symptoms such as wheal, flare and itch in CSU patients.

The autologous serum skin test (ASST) involves an intradermal injection of autologous serum, while the autologous plasma skin test (APST) involves an intradermal injection of autologous plasma. Both tests are easy to use in practice and have been used to help diagnosis autoimmune urticaria. The in vitro basophil histamine release test is the gold standard for the detection of functional autoantibodies in patients with CSU [10]. In addition, positive autoreactivity (by means of a positive ASST or ASST) demonstrates relevance in vivo to mast cell degranulation and vasopermeability [10]. The serum of positive ASST and plasma of positive APST in CSU patients contains the same autoantibodies (anti-FcεRI and anti-IgE) to induce histamine release from mast cells and basophils. The difference between serum and plasma involves coagulation factors. An intradermal injection of plasma in place of serum significantly increases vascular permeability [11].

Factors to predict remission and severity of CSU are confined. Patients with autoantibodies may have severe urticaria symptoms more than patients without autoantibodies, but recent studies have shown that ASST was not associated with disease severity [1213]. Serum vitamin D and clustering levels are associated with disease severity in CSU [141516]. Moreover, serum concentrations of interleukin (IL)-17, IL-23, and tumor necrosis factor-α are associated with CSU disease activity and ASST [17]. This study showed that simple tests such as ASST and APST could potentially predict 2-year remission rates of patients with CSU.

The study was a prospective observational study concerning 128 CSU adult patients. The patients were recruited and received treatment at the Allergy Clinic, Phramongkutklao Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand from 2012 to 2015. CSU was diagnosed based on a history of continuous or recurrent hives more than 6 weeks. Patients with physical urticaria or urticarial vasculitis were excluded. Patient characteristics data and basic laboratory tests were completed at the first visit. Severity of urticaria was measured by urticaria severity score (USS) that was included with 12 questions and 7 response options per question included in the final questionnaire [18]. The dermatology life quality index (DLQI) is a common test used as a quality of life measure [19]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Royal Thai Army Medical Department. All subjects gave their informed consent before participating.

CSU patients were treated following the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology/Global Allergy and Asthma European Network/European Dermatology Forum/World Allergy Organization guidelines to manage urticaria [20]. The CSU management guidelines suggest to identify and avoid certain stimulus, for example, drugs, physical stimuli, infectious agents and food allergy triggers [21]. The main option in treatment was at symptomatic relief to reduce the effect of histamines. Thus, continuous treatment with H1-antihistamines is the first-line drug in the treatment of CSU. The new generation of H1-antihistamines is safe and without side effects to the central nervous system function. The second-line drug is the up-dosing of H1-antihistamines to 4 fold above the recommended doses and suggesting for those patients with CSU not responding to a single dose [22]. However, some patients not responding to the 4-fold dose of H1-antihistamine (histamines refractory patients) need treatment with a third-line drug (ciclosporin A, montelukast, omalizumab, hydroxycholoquine, and dapsone). A short course of oral prednisolone is used to treat patients with severe urticaria symptoms that induces remission in nearly 50% of patients with CSU [23]. Remission in the study is defined as no urticaria symptoms for at least 4 weeks without medication.

Patients were treated with antihistamine drugs and then stopped for at least 5 days. All patients underwent intradermal testing with 0.05 mL of autologous serum (ASST), heparin anticoagulated autologous plasma (APST) and saline as negative control. The serum was prepared by collecting whole blood in a covered test tube and then allowing the blood to clot by leaving it undisturbed at room temperature for 15 minutes. Afterwards, the test tube is centrifuged at 1,250 g for 10 minutes and the resulting supernatant becomes the designated serum. To prepare plasma, cells are removed from plasma by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 1,250 g using a refrigerated centrifuge and the resulting supernatant is designated plasma. Both serum and plasma intradermal tests were performed according to guidelines and read after 30 minutes intradermal injection [20]. A positive result was defined as the appearance of a serum or plasma induced wheal 1.5 mm thick or more than the saline-induced response at 30 minutes. If the patients had a positive autologous skin test, the longest and the shortest diameters of the wheal were measured and calculated as the mean wheal diameter. Skin prick tests (SPTs) were performed with 28 standard aeroallergens including house dust mite (HDM), Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farina and 20 standard common food allergens (Greer, Le Noir, NC and Alk-abello, Round Rock, TX, USA). Negative control was performed using 50% glycerine while 10 mg/mL of histamine solution was used for the positive control. SPTs were positive when the size of the wheal was more than 3 mm in diameter and larger than the negative control.

In evaluating the clinical characteristics of patients, data were analyzed by analysis of variance, Fisher exact test and chi-square test. Data for continuous variables are shown as mean ± standard deviation. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare USS and DLQI scores between the groups. Correlation between ASST and APST with characteristics, laboratory and USS and DLQI were assessed by Spearman rank test. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant with confidence interval (CI) of 95%.

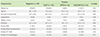

The patient characteristics of negative, positive ASST, positive APST, and both positive ASST and APST are shown in Table 1. One hundred and twenty-eight adult patients (43 male and 85 female patients) were enrolled in the study and females revealed a significant difference between the groups (p = 0.02). Mean age was 34.8 ± 10.9 years old and mean duration of disease was 25.5 ± 21.3 weeks. Seven urticaria patients had angioedema and 8 patients had comorbid disease with allergic rhinitis (AR). Mean erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 22.6 ± 10.4 minutes. Fifty-seven patients (44.5%) had positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA, > 1:80). Forty-six patients with positive thyroid autoantibody (positive antithyroglobulin or antithyroid peroxidase antibody) were observed. Eighty-one patients (63.2%) and 24 patients (18.7%) presented positive SPT HDM and positive SPT food allergens. No significant difference was found between the groups in age, urticaria duration, angiodedema, comorbid disease with AR, ESR, positive ANA, positive thyroid autoantibody, positive SPT HDM, and positive SPT food allergens.

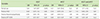

A total of 84 patients (65.6%) had a positive reaction in the autologous skin test. Of 47 patients (37%), 6 patients (5%) and 31 patients (24%) had positive ASST, positive APST, and both positive ASST and APST, respectively (Fig. 1A). The positive ASST was 79 of 124 (63.7%) and the positive APST was 37 of 124 (29.8%). The odds of females having a positive ASST was significantly more than males (odds ratio [OR], 3.64; 95% CI, 1.47–8.97; p = 0.005) (Table 2). In addition, positive SPT HDM tended to be an increased positive ASST (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 0.75–4.17) and both positive ASST and APST (OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 0.76–5.41), although significance was not reached (Table 2).

Positive ASST and APST at baseline revealed no difference in urticaria severity and quality of life among patients with CSU. No significant differences were observed between the groups with mean USS (Fig. 1B) and DLQI scores (Fig. 1C). In the study, we showed a positive significant correlation between USS and DLQI (r = 0.84, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A). The investigation reactions to ASST and APST association with USS and DLQI were observed. Mean wheal diameter of positive ASST correlated with USS (r = 0.24, p = 0.02) (Fig. 2B), with no significant association with DLQI (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the size of the wheal in positive APST patients correlated with USS (r = 0.57, p = 0.0002) (Fig. 2D) and DLQI (r = 0.57, p = 0.0002) (Fig. 2E).

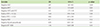

We analyzed after conducting the prospective study 4 weeks. Fifty-four patients of 128 (42.2%) received a 4-fold dose of H1-antihistamine (second-line drug) to control urticaria symptoms. Also, the proportion of patients refractory to a 4-fold dose of H1-antihistamine was significantly higher in the both positive ASST and APST groups than in the positive ASST (p = 0.03) and negative groups (p = 0.0009) (Fig. 3A). Approximately one quarter of the patients were treated with short-course oral prednisolone. Thus, no significant differences were observed regarding taking short-course oral prednisolone between the groups (Fig. 3B).

Among a total of 128 patients, 107 (83.5%) completed 2 years observational study. During the 2 years, 58 patients took a third-line drug (montelukast 40.4%, ciclosporin A 26.9%, hydroxycholoquine 19.2%, and dapsone 13.5%). However, the rate of third-line drug treatment presented no significant difference between the groups (Fig. 3C). Our results showed 69 patients (64.4%) achieved remission over 2 years. The patients in the negative group had complete remission 62.1% at the first year and 81.1% at the second year. In addition, the rate of remission during 2 years in the positive ASST, positive APST, and both positive ASST and APST groups were 62.3%, 60%, and 46.1%, respectively (Fig. 3D). The urticaria remission rate in patients in the negative group was 5 times significantly higher compared with both positive ASST and APST groups (OR, 5.0; 95% CI, 1.61–15.44; p = 0.006). However, no significant difference was observed between the negative and positive ASST groups or the positive APST group.

The predictors of urticaria remission were analyzed (Table 3). Negative ASST was a significant determinant of urticaria remission (OR, 3.97; 95% CI, 1.47–9.43; p = 0.001). Furthermore, negative APST had the chance to achieve remission more than positive APST (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.11–6.19; p = 0.04). Moreover, baseline negative ASST and APST was 4.5 times as likely as positive autologous to be in remission. Mean wheal diameter of positive ASST <15 mm had odds of 3.44 to achieve remission more than wheal >15 mm. In addition, patients with negative SPT HDM achieved urticaria remission 1.46 times positive SPT HDM.

Next, we analyzed urticaria remission time associated with urticaria severity and autologous skin test. No correlation was observed between urticaria remission time with baseline DLQI (Fig. 4A) and USS scores (Fig. 4B). We found a positive correlation between mean wheal diameter of positive ASST and urticaria remission time (r = 0.39, p = 0.01) (Fig. 4C). Moreover, a large mean wheal diameter of positive APST showed prolonged urticaria remission time (r = 0.55, p = 0.03) (Fig. 4D).

We reported a high rate of positive ASST among patients with CSU. On the other hand, the rate of positive APST in our study was lower compared with other studies. The prevalence of positive ASST and positive APST among CSU patients was 25% to 66% and 45% to 85%, respectively [24252627282930]. The prevalence of positive autologous skin test varied depending on the country and the defined term of positive ASST and APST. The multicenter study by Metz et al. [31] reported that the rate of positive APST was 43%, using sodium citrate, an effective anticoagulant. Heparin was used as an anticoagulant in our study. Although heparin may block degranulation of mast cells and basophils in vivo and in vitro studies, it could explain the low positive APST result in our study [323334]. Coagulation activation related to pathophysiology of CSU. Prothrombin fragment 1+2, D-dimer and C-reactive protein of CSU patients were higher than the healthy control group [35]. Furthermore, after the disease remission, patients with CSU had a significantly reduced plasma prothrombin fragment 1+2 and D-dimer [35]. Plasma soluble CD40 concentration increased in patients with CSU with positive ASST that may indicate CD40/CD40L interaction plays a role in immune activation in autoimmune urticaria. From this study, we could not conclude that ASST is a better test than APST to diagnose autoimmune urticaria.

The study showed urticaria disease severity between the result of negative and positive autologous skin revealed no significant difference. However, positive autologous skin test correlated with disease severity. The studies by Sabroe et al. [1226] reported that patients with autoantibodies had more severity than patients without autoantibodies according to urticaria disease severity. In addition, recent studies reported positive and negative ASST showed no significant difference in accordance with laboratory and urticaria disease severity [132836]. Our result in this study was similar to the study by Kocatürk et al. [37] reporting no significant difference between positive ASST/negative APST and positive APST/negative ASST patients regarding disease duration, urticaria activity scores and DLQI scores.

According to the result of this study, we suggested testing ASST and APST together to predict long-term remission. Also, the negative result of ASST and APST served as a good predictor to achieve urticaria remission in 2 years. Positive ASST and APST in CSU patients could be used to estimate the duration and severity of CSU [25]. Furthermore, Toubi et al. [4] showed patients with CSU and angioedema were associated with disease duration and CSU duration was associated with the presence of both ASST and antithyroid antibodies. Moreover, Ye et al. [38] reported the proportion of CSU patients that achieved remission or a good level of control was 39% for the 6 months of stepwise treatment. In addition, positive ASST was a significant predictor of CSU control (OR, 6.10; p = 0.01) [38]. Positive ASST and APST results among patients with CSU may indicate difficult treatment and prolonged disease duration.

Concerning the study, we found a high rate of CSU patients had sensitivity to HDM. However, our positive SPT HDM data could not show significant differences between groups. HDM sensitivity was possibly associated with chronic urticaria [39]. Recent studies showed 25% to 58% of CSU patients had positive SPTs and specific IgE antibodies against HDM [404142]. Patients with positive ASST and/or positive SPTs to HDM had more disease activity compared with patients with negative ASST or negative SPT [40]. Moreover, food hypersensitivity is a common cause of acute urticaria. However, CSU induced by food allergy was found in only 2.8% of patients [43]. HDM sensitivity may be related to urticaria symptoms and remission rate, but is unrelated to ASST and APST.

Limitations of the study included the low number of patients in the only positive APST group, making it difficult to show statistical significance. Further study should be done with large sample size and prolong duration observation. We were limited to treating the third-line drug, especially omalizumab among patients with CSU because the cost of omalizumab is expensive. However, ciclosporin A and hydroxycholoquine were effective third-line medications used in this study.

In conclusion, the study found a high rate of positive ASST among patients with CSU and autoimmunity related to disease duration. At baseline, no significant difference was found regarding baseline disease severity and quality of life between the patients with negative and positive autologous test. However, the negative result of ASST and APST before treatment was a predictor of good prognosis treatment and urticaria remission during the 2-year observational study. Furthermore, HDM allergy was at a high incidence rate among CSU patients but without significant influence regarding disease remission. We recommend investigating ASST and APST among CSU patients.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Distribution of chronic spontaneous urticaria based on the result of autologous serum skin test (ASST) and autologous plasma skin test (APST) (n = 128). Box and whiskers plot 10th–90th percentile revealed a comparison of urticaria severity score (USS) (B) and dermatology life quality index (DLQI) (C) among negative, positive ASST, positive APST, and both positive ASS and APST groups. |

| Fig. 2(A) Correlation graph between urticaria severity score (USS) and dermatology life quality index (DLQI) among chronic spontaneous urticaria patients (n = 128). Representative correlation graphs between diameters of positive autologous serum skin test (ASST) with USS (B) and DLQI (C). The correlation graphs show diameters of positive autologous plasma skin test (APST) correlated with USS (D) and DLQI (E). Spearman's test was used to analyze the data. NS, not significant. |

| Fig. 3Proportion of the patients with chronic urticaria compare among negative, positive autologous serum skin test (ASST), positive autologous plasma skin test (APST), and both positive ASST and APST groups. Four-fold dose of H1- antihistamine during 4 weeks of treatment (A), short-course oral prednisolone (B), and third-line drug treatment during 2 years (C) were observed. (D) A Kaplan-Meier curve graph demonstrates the remission rate among the groups (n = 107). Statistical analysis was performed by Fisher exact test. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. |

| Fig. 4Correlation of remission time and dermatology life quality index (DLQI) (A), urticaria severity score (USS) (B), wheal diameter of autologous serum skin test (ASST) (C), and wheal diameter of autologous plasma skin test (APST) (D). Spearman test was used to analyze the data. NS, not significant. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Phramongkutklao Hospital. The authors wish to acknowledge Mrs. Jitta Tubkate and Dr. Chidchai Kuruchitkosol for help in performing autologous skin test and contacting the patients.

References

1. Ozkan M, Oflaz SB, Kocaman N, Ozseker F, Gelincik A, Büyüköztürk S, Ozkan S, Colakoğlu B. Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007; 99:29–33.

2. Engin B, Uguz F, Yilmaz E, Ozdemir M, Mevlitoglu I. The levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008; 22:36–40.

3. Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C, Giménez-Arnau A, Bousquet PJ, Bousquet J, Canonica GW, Church MK, Godse KV, Grattan CE, Greaves MW, Hide M, Kalogeromitros D, Kaplan AP, Saini SS, Zhu XJ, Zuberbier T. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011; 66:317–330.

4. Toubi E, Kessel A, Avshovich N, Bamberger E, Sabo E, Nusem D, Panasoff J. Clinical and laboratory parameters in predicting chronic urticaria duration: a prospective study of 139 patients. Allergy. 2004; 59:869–873.

6. Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 114:465–474.

7. Hide M, Francis DM, Grattan CE, Hakimi J, Kochan JP, Greaves MW. Autoantibodies against the high-affinity IgE receptor as a cause of histamine release in chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:1599–1604.

8. Sabroe RA, Fiebiger E, Francis DM, Maurer D, Seed PT, Grattan CE, Black AK, Stingl G, Greaves MW, Barr RM. Classification of anti-FcepsilonRI and anti-IgE autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria and correlation with disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 110:492–499.

9. Tedeschi A, Kolkhir P, Asero R, Pogorelov D, Olisova O, Kochergin N, Cugno M. Chronic urticaria and coagulation: pathophysiological and clinical aspects. Allergy. 2014; 69:683–691.

10. Konstantinou GN, Asero R, Ferrer M, Knol EF, Maurer M, Raap U, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Skov PS, Grattan CE. EAACI taskforce position paper: evidence for autoimmune urticaria and proposal for defining diagnostic criteria. Allergy. 2013; 68:27–36.

11. Asero R, Tedeschi A, Riboldi P, Cugno M. Plasma of patients with chronic urticaria shows signs of thrombin generation, and its intradermal injection causes wheal-and-flare reactions much more frequently than autologous serum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 117:1113–1117.

12. Sabroe RA, Seed PT, Francis DM, Barr RM, Black AK, Greaves MW. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: comparison of the clinical features of patients with and without anti-FcepsilonRI or anti-IgE autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 40:443–450.

13. Caproni M, Volpi W, Giomi B, Cardinali C, Antiga E, Melani L, Dagata A, Fabbri P. Chronic idiopathic and chronic autoimmune urticaria: clinical and immunopathological features of 68 subjects. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004; 84:288–290.

14. Kim JH, Lee HY, Ban GY, Shin YS, Park HS, Ye YM. Serum clusterin as a prognostic marker of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95:e3688.

15. Woo YR, Jung KE, Koo DW, Lee JS. Vitamin D as a Marker for disease severity in chronic urticaria and its possible role in pathogenesis. Ann Dermatol. 2015; 27:423–430.

16. Boonpiyathad T, Pradubpongsa P, Sangasapaviriya A. Vitamin d supplements improve urticaria symptoms and quality of life in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients: a prospective case-control study. Dermatoendocrinol. 2014; 6:e29727.

17. Atwa MA, Emara AS, Youssef N, Bayoumy NM. Serum concentration of IL-17, IL-23 and TNF-α among patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: association with disease activity and autologous serum skin test. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014; 28:469–474.

18. Jariwala SP, Moday H, de Asis ML, Fodeman J, Hudes G, de Vos G, Rosenstreich D. The Urticaria Severity Score: a sensitive questionnaire/index for monitoring response to therapy in patients with chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009; 102:475–482.

19. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994; 19:210–216.

20. Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Walter Canonica G, Church MK, Giménez-Arnau AM, Grattan CE, Kapp A, Maurer M, Merk HF, Rogala B, Saini S, Sánchez-Borges M, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Schünemann H, Staubach P, Vena GA, Wedi B. Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Global Allergy and Asthma European Network. European Dermatology Forum. World Allergy Organization. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: management of urticaria. Allergy. 2009; 64:1427–1443.

21. Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Brzoza Z, Canonica GW, Church MK, Ensina LF, Giménez-Arnau A, Godse K, Gonçalo M, Grattan C, Hebert J, Hide M, Kaplan A, Kapp A, Abdul Latiff AH, Mathelier-Fusade P, Metz M, Nast A, Saini SS, Sánchez-Borges M, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Simons FE, Staubach P, Sussman G, Toubi E, Vena GA, Wedi B, Zhu XJ, Maurer M. European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Global Allergy and Asthma European Network. European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization. The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014; 69:868–887.

22. Staevska M, Popov TA, Kralimarkova T, Lazarova C, Kraeva S, Popova D, Church DS, Dimitrov V, Church MK. The effectiveness of levocetirizine and desloratadine in up to 4 times conventional doses in difficult-to-treat urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125:676–682.

23. Asero R, Tedeschi A. Usefulness of a short course of oral prednisone in antihistamine-resistant chronic urticaria: a retrospective analysis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010; 20:386–390.

24. Zhong H, Song Z, Chen W, Li H, He L, Gao T, Fang H, Guo Z, Xv J, Yu B, Gao X, Xie H, Gu H, Luo D, Chen X, Lei T, Gu J, Cheng B, Duan Y, Xv A, Zhu X, Hao F. Chronic urticaria in Chinese population: a hospital-based multicenter epidemiological study. Allergy. 2014; 69:359–364.

25. Sajedi V, Movahedi M, Aghamohammadi A, Gharagozlou M, Shafiei A, Soheili H, Sanajian N. Comparison between sensitivity of autologous skin serum test and autologous plasma skin test in patients with Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria for detection of antibody against IgE or IgE receptor (FcεRIα). Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011; 10:111–117.

26. Sabroe RA, Grattan CE, Francis DM, Barr RM, Kobza Black A, Greaves MW. The autologous serum skin test: a screening test for autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1999; 140:446–452.

27. Guttman-Yassky E, Bergman R, Maor C, Mamorsky M, Pollack S, Shahar E. The autologous serum skin test in a cohort of chronic idiopathic urticaria patients compared to respiratory allergy patients and healthy individuals. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007; 21:35–39.

28. Kulthanan K, Jiamton S, Gorvanich T, Pinkaew S. Autologous serum skin test in chronic idiopathic urticaria: prevalence, correlation and clinical implications. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2006; 24:201–206.

29. Taskapan O, Kutlu A, Karabudak O. Evaluation of autologous serum skin test results in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria, allergic/non-allergic asthma or rhinitis and healthy people. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008; 33:754–758.

30. Yıldız H, Karabudak O, Doğan B, Harmanyeri Y. Evaluation of autologous plasma skin test in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2011; 165:1205–1209.

31. Metz M, Giménez-Arnau A, Borzova E, Grattan CE, Magerl M, Maurer M. Frequency and clinical implications of skin autoreactivity to serum versus plasma in patients with chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 123:705–706.

32. Ahmed T, Abraham WM, D'Brot J. Effects of inhaled heparin on immunologic and nonimmunologic bronchoconstrictor responses in sheep. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992; 145:566–570.

33. Lucio J, D'Brot J, Guo CB, Abraham WM, Lichtenstein LM, Kagey-Sobotka A, Ahmed T. Immunologic mast cell-mediated responses and histamine release are attenuated by heparin. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1992; 73:1093–1101.

34. Baram D, Rashkovsky M, Hershkoviz R, Drucker I, Reshef T, Ben-Shitrit S, Mekori YA. Inhibitory effects of low molecular weight heparin on mediator release by mast cells: preferential inhibition of cytokine production and mast cell-dependent cutaneous inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997; 110:485–491.

35. Cugno M, Tedeschi A, Borghi A, Bucciarelli P, Asero R, Venegoni L, Griffini S, Grovetti E, Berti E, Marzano AV. Activation of blood coagulation in two prototypic autoimmune skin diseases: a possible link with thrombotic risk. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0129456.

36. Nettis E, Dambra P, D'Oronzio L, Cavallo E, Loria MP, Fanelli M, Ferrannini A, Tursi A. Reactivity to autologous serum skin test and clinical features in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002; 27:29–31.

37. Kocatürk E, Kavala M, Kural E, Sarıgul S, Zındancı I. Autologous serum skin test vs autologous plasma skin test in patients with chronic urticaria: evaluation of reproducibility, sensitivity and specificity and relationship with disease activity, quality of life and anti-thyroid antibodies. Eur J Dermatol. 2011; 21:339–343.

38. Ye YM, Park JW, Kim SH, Ban GY, Kim JH, Shin YS, Lee HY, Park HS. PRANA Group. Prognostic factors for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a 6-month prospective observational study. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016; 8:115–123.

39. Mahesh PA, Kushalappa PA, Holla AD, Vedanthan PK. House dust mite sensitivity is a factor in chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005; 71:99–101.

40. Song Z, Zhai Z, Zhong H, Zhou Z, Chen W, Hao F. Evaluation of autologous serum skin test and skin prick test reactivity to house dust mite in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e64142.

41. Caliskaner Z, Ozturk S, Turan M, Karaayvaz M. Skin test positivity to aeroallergens in the patients with chronic urticaria without allergic respiratory disease. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004; 14:50–54.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download