Abstract

Background

Asthma in the elderly is severe and associated with poor treatment outcome. Although atopy has an important role in pathogenesis, its role in the elderly is unclear, partly due to immune senescence.

Objective

We aimed to examine the associations of Th2-mediated inflammation with asthma severity in the elderly.

Methods

Consecutive asthmatics older than 60 years without severe exacerbation within 8 weeks were enrolled. Atopic status was determined by positive serum specific IgE or skin prick test to common aeroallergens. Serum total IgE was measured simultaneously to exhaled fractional concentration of nitric oxide (FeNO). Asthma control level was assessed by using Thai Asthma Control Test (ACT) score.

Results

Total of 44 elderly asthmatic patients were enrolled. The mean age was 68.9 years and mean age of asthma diagnosis was 46.6 years. Seventy-seven percent of patients were female. Atopic status was found in 45.5% of patients. Uncontrolled asthma classified as ACT score < 20 was noted in 25% of elderly asthma, but its association with either high serum total IgE (≥120 IU/mL), high FeNO (≥50 ppb) or atopic status was not detected.

Conclusion

One-fourth of elderly asthmatics were clinically uncontrolled, while atopy was confirmed in 45.5%. Neither high total IgE, high FeNO nor atopic status was associated with uncontrolled asthma in the elderly. Other factors might play role in asthma severity in the elderly, and has to be further investigated.

Asthma is a common chronic respiratory disease [1]. Despite the fact that asthma commonly affects children and young adult, its prevalence in the elderly is not uncommon [2]. Because elderly population become increasing worldwide includes Thailand. Asthma in the elderly is associated with increase health burden and medical resource utilization [3456]. For example, elderly is associated with asthma-related high morbidity and mortality apart from other modifiable factors such as smoking status and depression [6].

Allergen-specific IgE production and eosinophillic inflammation underlie pathogenesis of asthma [7]. Moreover, atopic status has been demonstrated to be associated with increasing asthma severity and requiring high intensity of therapies in elderly [8]. However, age-related immune dysfunction might influence allergy test results. Despite association of serum total IgE and probability of being diagnosed asthma [9], the number of positive allergen detected from skin test and serum total IgE declined in asthmatic patients overtime [1011].

Skin prick test (SPT) or serum specific IgE to aeroallergens have been practically used to confirm atopy [12]. Several limitations are concerned. Serum specific IgE measurement is expensive and might be irrelevant in the absence of clinical ground [13]. Skin fragility and wrinkle in aged population may interfere skin test sensitivity and specificity [14]. Eosinophillic airway inflammation is a hallmark of asthma, eventhough neutrophilic asthma was noted in severe asthma [1516]. Fractional exhaled concentration of nitric oxide (FeNO) is fairly correlated with sputum eosinophillia in asthma [17] and it has been widely used for asthma monitoring. However, the role of FeNO as surrogate marker of airway eosinophilia in elderly is still uncertain. We hypothesized whether Th2 polarization measured by serum IgE and FeNO were associated with asthma control in elder asthmatics. In addition, the role of atopy on elderly asthmatics was investigated.

A cross-sectional study was conducted at pulmonary and allergy clinic, Department of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital. Consecutive elderly asthmatic patients defined as age ≥ 60 years, diagnosed according to Global Initiative for Asthma guideline during June 2013 to February 2014 were enrolled. Patients with exacerbation within 8 weeks before enrollment, defined as oral prednisolone burst, emergency room visits or hospitalization were excluded. All patients provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Research Ethic Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital.

Patients' demographic data including age, gender, age of asthma diagnosis, body mass index (BMI), family history of atopy, and history of smoking (current, past or passive) were recorded. The current treatment of asthma, comorbidities and pulmonary functions were retrieved from medical record. Allergic symptoms, including nasal and conjunctival symptoms were collected using self-answered questionnaire.

SPT to common aeroallergen comprising of house dust mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus [Dp] and Dermatophagoides farinae [Df]), house dust, cockroach, pollens (Bermuda, Timothy, Johnson grass, Careless weed, and Acacia), cat, dog, mixed features (poultry), and molds (Candida, Aspergillus fumigatus, Moldmix I, and Trichophyton) was done in all patients, while histamine 10 mg/mL was used as positive control. Atopic status was defined if at least one aeroallergen was positive by producing wheal > 3 mm after 15 minutes. In addition, serum total IgE was measured using enzyme linked immunoassay (ELISA, Phadia, Sweden) and data were expressed in IU/mL. High serum total IgE was define as level of more than 120 IU/mL [1819], according to laboratory cutoff. Two allergen-specific IgE were measured using fluroenzyme immunosorbent assay (CAP-System-FEIA, Phadia, Sweden) that were Dp and A. fumigatus, because Dp is the most common sensitizing aeroallergen in Thailand [20] and concordance between serum specific IgE and SPT results is usually high, but not for A. fumigatus [13]. Specific IgE level ≥ 0.35 KAU/L was interpreted as positive. Fractional concentration of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was measured using electrochemical technique (NOBREATH, Bedfont, UK) as previously described [21]. Data were expressed as part per billion (ppb). FeNO level less than 50 ppb was defines as low FeNO, while level more than 50 ppb was interpreted as high FeNO [22]. Asthma control was measured using Thai Asthma Control Test (ACT) version (score, 5–25). The score of less than 20 was considered uncontrolled asthma.

Continuous variables were analyzed by using mean, standard deviation and median as appropriate for their normal distribution. The association of 2 categorical data was analyzed using Pearson chi-square test. Data were collected and analyzed by using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) and p value of < 0.05 was considered statistical significance.

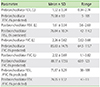

A total of 44 patients were enrolled to the study. Baseline characteristics of patient were shown in Table 1. Patients' mean age was 68.9 ± 6.32 years and mean age of asthma onset was 46.6 ± 20.67 years. Seventy-seven percent of patients were female. Mean BMI was 25.2 ± 5.05 kg/m2. History of nasal and conjunctival symptoms were noted in 77.3% and 54.5% of patients, respectively, while current naso-ocular symptoms and allergic rhinitis was present in 36%. Family history of atopy was noted in 36.4%.

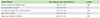

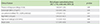

Mean pre- and postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second were 71.1% ± 9.9% and 76.8% ± 10.24% of normal predicted value (Table 2). Mean ACT score was 21.4 ± 3.5 and uncontrolled asthma classified as ACT score < 20 was noted in 25% of patients. FeNO was 57.1 ± 25.8 and high FeNO (≥50 ppb) was noted in 46.2% of patients. Median serum total IgE was 92.4 IU/mL ranging from 3.6–5,531 IU/mL. High serum total IgE (> 120 IU/mL) was noted in 41% of patients. Detail of ACT score, serum total and specific IgE level, FeNO and SPT results were shown in Table 3. SPT positivity was noted in 16 patients (42.1%). However, when atopic status was determined by either positive serum specific IgE level or positive SPT for aeroallergen, number of allergic patients was increased to 20 patients (45.5%). Common aeroallergen identified were house dust mite Df, Dp, cockroach, house dust, and Bermuda grass, respectively. No positive SPT for careless weed, Acacia, Candida or Trichophyton was found (Table 3).

There was association between the presence of high serum total IgE level (≥120 IU/mL) and atopic status using either SPT or serum specific IgE (p = 0.03) (Table 4). Positive serum specific IgE for Dp was significant correlated with SPT result (p < 0.01), but not for Aspergillus (p = 0.28). However, the association between uncontrolled asthma (ACT score < 20) and FeNO, atopic status, high serum total IgE level or high FeNO were not observed (Table 5).

Uncontrolled asthma assessed by low ACT was noted in one-fourth of the elderly asthmatics in this study despite intensive therapies. One reason may be underrecognized and undertreated allergic component in asthma. The other is aged-related physical impairment and decline in lung function [23]. In this study, atopic status in the elderly was common and observed in nearly half of the subjects. However, the association of atopic status and asthma control using ACT score was not demonstrated [9]. Despite previous study that had shown the association of increased serum IgE level and probability of being asthma, there is no association of high serum IgE level and poor asthma control in our study. In addition, exhaled nitric oxide which is a biomarker of eosinophillic airway inflammation and has been shown to link to asthma severity, was not shown to be associated with low ACT in our study.

Because of the heterogeneity of disease, particularly in severe asthma, Th2-mediated inflammation might not be the sole influence on asthma severity, especially in senile subpopulation. These findings were different from previous study involving younger population, which have shown the correlation between numbers of sensitized aeroallergen detected by SPT and asthma severity. Even though age-related decline in immune reaction is anticipated in elder asthmatic, atopy was still detected in 45% of the patients. However, its influence on senile asthma severity was inconsistent since we did not found the association between atopic status, high serum total IgE level and high FeNO with poor asthma control. Presence of specific IgE or positive SPT merely represented sensitization, and serum IgE level did not always correlate with allergic symptoms [24]. We have observed history of nasal and ocular symptoms in 77.3% and 54.5% of patients, respectively, while only 36% had current allergic rhinitis as comorbid. Further study involved larger sample size to measure atopic status, allergen exposure and clinical severity as well as effort to discover new markers of allergic inflammation in senile patients are still needed. We suggested that determination of atopic status using either SPT or serum specific IgE should be conducted in severe asthma in all age groups. However, the value of the tests and interpretation should rely on clinical relevance [24]. Regarding atopic status, house dust mites was the most common aeroallergen detected in elderly asthma similar to other age group. The concordance between in vitro and in vivo test for house dust mite was very high as all patients sensitized to house dust mites gave positive results to both techniques except 2 patients whom one was positive only to SPT and another was positive only to specific IgE. In contrast, the lack of concordance between serum specific IgE for A. fumigatus and SPT was observed as none of the patients gave positive results to both tests, which are similar to previous reports [13]. This should raise awareness to the physician to select appropriate tests in order to increase sensitivity in diagnosis of sensitization for different allergen [24]. Furthermore, the association between high serum total IgE level (>120 IU/mL) and atopic status was noted, which might be explained by increase circulatory pool of IgE driven by aeroallergen sensitization. This finding supports the role of specific or targeted therapies such as anti-IgE monoclonal antibody (omalizumab) in severe allergic asthma with high IgE. In the present study, there were 4 of our elderly asthmatic patients (9.1%) whom received omalizumab as add-on therapy. In comparison to INNOVATE study, median age of omalizumab treated patients was 44.0 years ranging from 12 to 79 years [25]. Therefore, high serum total IgE should raise awareness of atopy in the elderly in the setting of limited specific allergen test. However, determination of specific allergen sensitization remains crucial in diagnosis of allergy, its relevance to the disease should rely on clinical context of individual patient.

Severe asthma in the elderly is multifacet disease, longstanding disease might be explained by ineffective pharmacotherapy, absence of risk factor modification, undertreated comorbidities or lack of self-management program [23]. Not only identifying risk factors of allergic disease, but also vigorous management of disease in specific asthma patients is crucial to achieve asthma control.

In conclusion, the prevalence of atopy in elderly asthma was not uncommon. Although, immune-senescence process may influence allergic testing in elderly, up to 45% of elderly asthmatics gave positive results on allergy testing. However, the influence of atopic status and marker of eosinophilic inflammation on asthma control was not observed in elderly asthma population in our study. Because asthma is multifactorial disease, contributing factors other than atopy such as comorbid diseases, irreversible airway obstruction or impaired physical status must be considered in order to achieve asthma control.

Figures and Tables

Table 3

ACT score, fractional exhale nitric oxide, serum total and specific IgE level and skin prick test results

References

1. The Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention (2015 update) [Internet]. The Global Initiative for Asthma;cited 2015 Jul 15. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/documents/5/documents_variants/59.

2. Oraka E, Kim HJ, King ME, Callahan DB. Asthma prevalence among US elderly by age groups: age still matters. J Asthma. 2012; 49:593–599.

3. Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board of Thailand. Report of the elderly population in Thailand. Bankok (TH): Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board of Thailand;2013.

4. Beck LA, Marcotte GV, MacGlashan D, Togias A, Saini S. Omalizumab-induced reductions in mast cell Fce psilon RI expression and function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 114:527–530.

5. Stupka E, deShazo R. Asthma in seniors: Part 1. Evidence for underdiagnosis, undertreatment, and increasing morbidity and mortality. Am J Med. 2009; 122:6–11.

6. Bellia V, Pedone C, Catalano F, Zito A, Davì E, Palange S, Forastiere F, Incalzi RA. Asthma in the elderly: mortality rate and associated risk factors for mortality. Chest. 2007; 132:1175–1182.

7. Storms W. Allergens in the pathogenesis of asthma: potential role of anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Am J Respir Med. 2002; 1:361–368.

8. Huss K, Naumann PL, Mason PJ, Nanda JP, Huss RW, Smith CM, Hamilton RG. Asthma severity, atopic status, allergen exposure and quality of life in elderly persons. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001; 86:524–530.

9. Borish L, Chipps B, Deniz Y, Gujrathi S, Zheng B, Dolan CM. TENOR Study Group. Total serum IgE levels in a large cohort of patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005; 95:247–253.

10. De Amici M, Ciprandi G. The age impact on serum total and allergen-specific IgE. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2013; 5:170–174.

11. Scichilone N, Callari A, Augugliaro G, Marchese M, Togias A, Bellia V. The impact of age on prevalence of positive skin prick tests and specific IgE tests. Respir Med. 2011; 105:651–658.

12. Chiriac AM, Bousquet J, Demoly P. In vivo methods for the study and diagnosis of allergy. In : Adkinson NF, Bochner BS, Burks AW, Busse WW, Holgate ST, Lemanske RF, O'Hehir RE, editors. Middleton's allergy principles and practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2013. p. 1119–1132.

13. O'Driscoll BR, Powell G, Chew F, Niven RM, Miles JF, Vyas A, Denning DW. Comparison of skin prick tests with specific serum immunoglobulin E in the diagnosis of fungal sensitization in patients with severe asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009; 39:1677–1683.

14. King MJ, Lockey RF. Allergen prick-puncture skin testing in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2003; 20:1011–1017.

15. Douwes J, Gibson P, Pekkanen J, Pearce N. Non-eosinophilic asthma: importance and possible mechanisms. Thorax. 2002; 57:643–648.

16. Haldar P, Pavord ID. Noneosinophilic asthma: a distinct clinical and pathologic phenotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 119:1043–1052.

17. Wang W, Huang KW, Wu BM, Wang YJ, Wang C. Correlation of eosinophil counts in induced sputum and fractional concentration of exhaled nitric oxide and lung functions in patients with mild to moderate asthma. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012; 125:3157–3160.

18. Sunyer J, Anto JM, Castellsague J, Soriano JB, Roca J. Total serum IgE is associated with asthma independently of specific IgE levels. The Spanish Group of the European Study of Asthma. Eur Respir J. 1996; 9:1880–1884.

19. Beeh KM, Ksoll M, Buhl R. Elevation of total serum immunoglobulin E is associated with asthma in nonallergic individuals. Eur Respir J. 2000; 16:609–614.

20. Kongpanichkul A, Vichyanond P, Tuchinda M. Allergen skin test reactivities among asthmatic Thai children. J Med Assoc Thai. 1997; 80:69–75.

21. Pisi R, Aiello M, Tzani P, Marangio E, Olivieri D, Chetta A. Measurement of fractional exhaled nitric oxide by a new portable device: comparison with the standard technique. J Asthma. 2010; 47:805–809.

22. Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, Irvin CG, Leigh MW, Lundberg JO, Olin AC, Plummer AL, Taylor DR. American Thoracic Society Committee on Interpretation of Exhaled Nitric Oxide Levels (FENO) for Clinical Applications. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 184:602–615.

24. Hamilton RG. Clinical laboratory assessment of immediate-type hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125:2 Suppl 2. S284–S296.

25. Humbert M, Beasley R, Ayres J, Slavin R, Hébert J, Bousquet J, Beeh KM, Ramos S, Canonica GW, Hedgecock S, Fox H, Blogg M, Surrey K. Benefits of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002 step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy. 2005; 60:309–316.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download