Abstract

Allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) is the only curative way that can change the immunologic response to allergens and thus can modify the natural progression of allergic diseases. There are some important criteria which contributes significantly on efficacy of AIT, such as the allergen extract used for treatment, the dose and protocol, patient selection in addition to the severity and control of asthma. The initiation of AIT in allergic asthma should be considered in intermittent, mild and moderate cases which coexisting with other allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis, and in case of unacceptable adverse effects of medications. Two important impact of AIT; steroid sparing effect and preventing from progression to asthma should be taken into account in pediatric asthma when making a decision on starting of AIT. Uncontrolled asthma remains a significant risk factor for adverse events and asthma should be controlled both before and during administration of AIT. The evidence concerning the efficacy of subcutaneous (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) for treatment of pediatric asthma suggested that SCIT decreases asthma symptoms and medication scores, whereas SLIT can ameliorate asthma symptoms. Although the effectiveness of SCIT has been shown for both seasonal and perennial allergens, the data for SLIT is less convincing for perennial allergies in pediatric asthma.

Asthma, is one of the most common chronic inflammatory disorder in children. Chronic inflammation is associated with airway hyper-responsiveness that induce recurrent episodes of wheezing, cough and chest tightness together with variable airflow obstruction. In the course of time, such airflow obstruction may become irreversible due to remodelling. Children have smaller airways than adults, which makes asthma especially serious for them. Left untreated, asthmatic children often have less endurance than other children, or avoid physical activities to prevent coughing or wheezing. Among children and adolescents aged 5 –17 years, asthma is responsible for a loss of 10 million school days annually [1].

It has been shown that there is no single asthma phenotype or definition of asthma from infancy to adulthood. Atopy is present in about 75% of all children with asthma [23]. Asthmatic children are commonly sensitized to indoor allergens, for example, house dust mite, cockroach, and furred pets.

All of the current natural history studies have shown that the presence of atopy and other allergic diseases are significant risk factors for persistent asthma. In the Berlin Multicentre Allergy Study, persistent sensitization to foods and perrenial inhalant allergens (i.e., dust mite, cat dander) were found as significant risk factors for asthma and bronchial hyperreactivity (BHR) at age 7 years [4]. Observational studies of asthma that have extended to adulthood also have found allergy to be a risk factor for persistent asthma [5].

Although some patients with allergy do experience a relative alleviation in symptoms with age, after eight years more than 85% were still symptomatic and 98% continuously had objective signs of allergic sensitization [6]. Atopic asthma in childhood with the tendency to persist into adult life is an important issue in pediatrics. Current asthma pharmacotherapies can effectively control symptoms and the on-going inflammatory process; however, they do not affect the underlying immune response. In most of the cases, when the drug treatment is ceased, relapses can arise and the disease may deteriorate.

Allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) is the only etiology-based therapy which has the power to modify natural evolution of the allergic disease as demonstrated by prevention of both the onset of new allergic sensitizations and disease progression. The efficacy of both subcutaneous (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) has been verified for both perennial and seasonal allergic respiratory disease by systematic reviews and meta-analyses [78910]. Because of its disease-modifying effects, AIT is the only real treatment way in allergic asthma [10].

The significance of immunotherapy in asthma based not only on its capacity to alter ongoing disease course but also on its ability to prevent progression of allergic disease. The latter involves hindered exacerbation of symptoms, preventing the development of asthma in children with allergic rhinitis and, also preventing development of new allergies [10]. Consequently, spending time, effort, and money on immunotherapy constitutes an investment that will give advantages from better prognosis and a mitigated burden of disease.

The objective of the current review was to summarize the efficacy and safety of allergen immunotherapy in pediatric asthma on guidance of the recent literature.

The study of Pifferi et al. [11] included 15 children aged 6–14 years with asthma due to house dust mite (HDM); SCIT was administrated for 3 years. They found significant decrease in asthma exacerbations and marked reduction in asthma symptoms and medication. The AIT group also showed a significant decrease in nonspecific BHR, although the same improvement was not observed in pulmonary functions (PFT).

Roberts et al. [12] enrolled 35 grass pollen allergic-asthmatic patients aged 3–16 years over 2 pollen season. They observed significant improvements in asthma symptom and medication scores as well as in cutaneous, conjunctival and bronchial reactivity to allergens; but, there was not found a significant difference in exhaled nitric oxide levels between active and placebo groups.

In another study, 15 mite-sensitive asthmatic children were treated with SCIT; the results were remarkable decrease in asthma symptom and medication scores in addition to improvement in allergen specific bronchial and skin reactivity [13].

Cantani et al. [14] administered SCIT with pollen or HDM to 300 asthmatic children for 3 years. They found that children receiving SCIT had significantly greater reductions in asthma symptoms and drug usage; moreover, the number of asthma attacks and the quality of life were significantly improved in the study group (p = 0.0001).

The study of Tabar et al. [15] investigating the efficacy of SCIT for 1 year with Alternaria alternata in 14 asthmatic children, demonstrated significant improvements in symptom and medication scores related with asthma and remarkable increases in peak expiratory flows.

Similarly, in the study of Kuna et al. [16], SCIT with Alternaria alternata administered to 30 children for 3 years. Although there was no significant change in year 1, the combined symptom medication score decreased in years 2 and 3 of the study (by 38.7% and 63.5%, respectively; p < 0.001 for each) and quality of life increased significantly.

Tsai et al. [17] treated 20 asthmatic children due to mites (aged 5–14 years) with SCIT; they reported AIT effectively reduced medication need and symptoms in children with allergic asthma; but, although the improvement in peak flow rate failed to reach statistical significance, a trend towards better performance was observed in the AIT group.

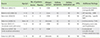

The double-blind placebo-controlled studies with SCIT in asthmatic children were summarized in Table 1.

In a recent Cochrane Database systematic review of SCIT, 88 studies on 3,459 subjects with asthma were evaluated; 16 out of 88 included studies included only in children below 18 years of age [18]. The results of this review were favorable toward SCIT in asthma; although both mite and pollen immunotherapy were found more effective on symptom scores, better outcomes were observed with pollen immunotherapy rather than mite immunotherapy. Reduction in medication use and diminished BHR were also reported with SCIT as part of this review.

Childhood is a critic period for rapid growth and development, and many pediatricians and specialists have sometimes difficulties about side-effects of long-term therapy with inhaled steroids or restricted use of long-acting beta agonists in children. The steroid sparing effect of AIT gives an important advantage in the management of childhood allergic asthma. For example, Zielen et al. [19] showed this steroid-sparing effect of SCIT in 65 HDM allergic children aged 6–17 years; the study group comprised of 2 arms; they are received subcutaneous allergoid immunotherapy plus fluticasone propionate (FP) or FP therapy alone for 2 years. After 2 years of treatment, the mean daily FP dose decreased from 330.3 µg to 151.5 µg in the immunotherapy group while there was no significant reduction in the control group.

In 2009, World Allergy Organization Position Paper on Sublingual Immunotherapy stated that SLIT is effective in the treatment of allergic rhinitis and asthma in children [20]. Most of the studies investigating the efficacy of SLIT comes from patients with rhinitis [212223]. There are some meta-analyses which have evaluated the efficacy of SLIT in children with rhinitis and/or asthma. One of the these meta-analyses carried out by Penagos et al. [24] evaluated 9 studies including 441 children; 232 and 209 of whom received SLIT and placebo, respectively. The results were significant decrease in asthma symptom scores and use of rescue medication.

Olaguibel et al. [25] performed a meta-analysis that assessed the efficacy of SLIT in children. Seven double-blind placebo-controlled trials, enrolling 256 children (129 treatment and 127 placebo recipients), were analyzed. Reductions in asthma (p = 0.01) and drug dosage (p = 0.06) scores reached statistical significance with the random effect model; neither severe nor systemic reactions were observed in studies included in meta-analyses.

The meta-analyses evaluating the efficacy of SLIT in asthmatic children were summarized in Table 2 [9242526272829].

In 2013 Update of World Allergy Organization Position paper [27], it was declared that grass or HDM SLIT can be used for allergic rhinitis in children with asthma, and HDM SLIT is effective in children with asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Larenas-Linnemann et al. [28] reviewed 28 clinic trials of SLIT in children published between 2009–2012. In 5 trials the principal disease was allergic asthma, caused by HDM (n = 3), grass (n = 1), or tree pollen (n = 1), with this latter being a safety study [3031323334]. Most data from asthma outcomes with pollen SLIT came from studies where seasonal allergic rhinitis was the leading disease and thus are studies not adequately designed or powered to detect changes in asthma symptoms or medication. The only grass pollen SLIT study in pediatric asthma reports encouraging data: asthma clinical parameters improved after 2 years of precoseasonal treatment comparing the active with the placebo group, reaching statistical significance even though the study was underpowered [30].

Mold allergy was addressed in one randomized controlled studies of Alternaria SLIT in respiratory allergy. After 3 years, symptom scores and inhaled corticosteroid use reduced, although total medication scores did not show any difference between the active and control groups [35]. The overall balance of the efficacy of SLIT with HDM as part of the integral treatment in pediatric asthma as studied in these trials is positive, but because the trials are small scientific quality is not optimal. Grass SLIT can be used for allergic rhinitis in children with asthma, but should never be used as monotherapy in children with active asthmatic symptoms. There is not enough evidence to recommend Alternaria SLIT in children. For seasonal asthma there is moderate evidence of a decrease in exhaled nitric oxide, but the quality of evidence for decrease in drug usage remains poor and the efficacy of grass pollen SLIT on asthma symptoms, PFT results, and nonspecific BHR is misty.

A recent meta-analyses assessed the efficacy and safety of dust mite SLIT in asthmatic children; 11 studies include a total of 454 children, 230 patients underwent SLIT treatment, and 224 were treated with placebo/pharmacotherapy for 4 months to 3 years [29]. It was found that the reduction in asthma symptoms and increase in sIgG4 levels were significantly greater in children treated with dust mite SLIT. However, it was shown that dust mite SLIT did not significantly decrease medication scores or specific Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus-specific IgE levels.

It can be summarized that although the efficacy of SLIT in seasonal allergic rhinitis is now well documented, the data for perennial allergies is less satisfying in children. Nonetheless, steroid sparing effect of SLIT was also demonstrated like SCIT in some studies which included asthmatic children. One of these studies including 602 asthmatic patients allergic to HDM, showed a reduced need for inhaled corticosteroids for asthma control with 1 year of treatment of HDM tablet [36].

Recently Cochrane Database systematic review about SLIT in asthma evaluated 52 studies with 5,077 participants mostly having mild or intermittent asthma; eighteen studies recruited only adults, 25 recruited only children and several enrolled both or did not specify (n = 9) [37]. The authors concluded that although a general tendency suggested SLIT benefit over placebo, there was a great heterogenity between studies, in addition to lack of data for important outcomes such as exacerbations and quality of life.

AIT is a treatment way which has disease-modifying effects. By this therapy, administering allergen extracts repeatedly during a long time, specific blocking antibodies, tolerance-inducing cells and mediators are activated. Thus, further exacerbation of the allergen-triggered immune response can be prevented, the specific immune response can be blocked and the inflammatory response in tissue can be reduced.

The Preventative Allergy Treatment (PAT) study enrolled 205 children (aged 6–10 years) suffering from allergic rhinitis, and randomized to either drug therapy alone or drugs plus SCIT. After 3 years, the SCIT-treated patients developed significantly less asthma than the control group (odds ratio, 2.5) [38].

A similar preventive effect was also shown with SLIT. The first open controlled study involved 113 children aged 5–14 years with seasonal rhinitis due to grass pollen, randomly allocated to pharmacotherapy plus SLIT or pharmacotherapy only. After 3 years, 8 of 45 SLIT patients and 18 of 44 controls had developed asthma, with a relative risk of 3 of 8 for untreated patients [39].

One of the most important long term ef fect of AIT is persistence of clinical and immunologic tolerance years after the stopping of treatment. At the 10-year follow-up (7 years after cessation of immunotherapy) the children in the immunotherapy group had significantly less asthma in comparison to the control group: 16 of 64 (25%) with asthma in the immunotherapy group compared with 24 of 53 (45%) of the untreated control group [40]. The authors concluded that immunotherapy for 3 years with grass and/or birch allergen extracts provides long-term preventive effect on the development of asthma in children with only seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis.

The other randomized open controlled trial [41] involved 216 children (5–17 years) having rhinitis with/without intermittent asthma, randomly allocated to drugs plus SLIT or drugs only. After three years of observation, the prevalence of persistent asthma was 1.5 % and 30% for SLIT and control group, respectively.

There are also some studies with both SCIT and SLIT which showed preventive effect of AIT against new sensitizations in patients with mono-allergen sensitivity [424344].

A large ongoing asthma prevention trial, the Grazax Asthma Prevention trial, is organized to evaluate the preventive ef fect of the SQ (standardized quality) grass SLIT tablet on the development of asthma in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Eight hundred twelve children were enrolled in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled multicenter study comprising 101 sites in 11 European countries [45]. The trial is designed with 3 years of treatment and 2 years of follow-up.

Local and systemic reactions are largely variable according to allergen extract, induction schedule, preparation and dose. The incidence of systemic reactions of SCIT varies between 0.06% and 1.01% in those administering injections [46]. Recently, a multicenter study demonstrated that systemic reactions were slightly more common in rhinitis with asthma than rhinitis alone [47]. Uncontrolled asthma and human mistakes were the most frequent causes of SCIT-induced adverse events [48]. As noted by official documents, the patients's general status and PFT should be assesed before each injection in order to reduce the risk of anapylaxis [49].

The safety of SLIT is better than that of SCIT [2850]; no fatality has been reported until now, and only few cases of suspected anaphylaxis have been described, none directly attributable to pre-existing asthma or to worsening of asthma [51]. Adverse events during SLIT occur mostly as local reactions (pruritus or dysesthesia in the oral cavity, swelling of the oral mucosa, throat irritation). These reactions usually appear during the initiation of SLIT, are mostly mild and generally subside 1 to 3 weeks after the beginning of treatment [28].

According to recent position paper on allergen immunotherapy, SLIT and SCIT can be used in patients with intermittent, mild and moderate asthma associated with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in addition to allergen avoidance and pharmacotherapy [54]. A remarkable clinical efficacy on asthma symptoms and a steroid-sparing effect is anticipated.

Allergen immunotherapy should be considered for children who have allergic asthma accompanied by allergic rhinitis/rhinoconjunctivitis, after natural exposure to allergens and who demonstrate specific IgE antibodies to relevant allergens. As mentioned above, there are many evidences showing that AIT is effective in controlling symptoms and in reducing drug intake in patients with asthma (usually accompanied by rhinitis) [55]. Therefore, SLIT and SCIT can be used along with asthma medications, when asthma is concomitant with rhinitis and the causal role of the allergen is clearly confirmed. Furthermore, when asthma is the only allergic disease (that is rare in children), AIT is expected to display a favourable effect. It does not seem that AIT can worsen asthma, whereas uncontrolled asthma remains a significant risk factor for adverse events. The disease modifying effects of AIT should be taken into account in pediatric allergic asthma.

The severity and duration of symptoms should also be considered in evaluating the need for allergen immunotherapy. Time lost from school, Emergency Department or physician's office visits, and response to pharmacotherapy are important objective indicators of allergic disease severity. The impact of the patient's symptoms on quality of life and response to allergen avoidance or medication, should also be factors for the judgement to recommend allergen immunotherapy. Patients with coexisting allergic rhinitis and asthma should be treated with an appropriate regimen of allergen avoidance measures and pharmacotherapy, but they may also benefit from allergen immunotherapy [56]. However, the patient's asthma must be stable before initation and during allergen immunotherapy.

Patients with severe or uncontrolled asthma are at increased risk for systemic reactions to immunotherapy injections [57]. Three surveys found that fatal and near-fatal reactions from immunotherapy injections were more common in patients with severe/labile asthma [14575859]. Therefore, allergen immunotherapy should not be started in patients with poorly controlled asthma symptoms [56]. Moreover, asthma control should be assessed at each injection visit.

Recent studies show an efficacy for SLIT on asthma symptoms in the subgroup of grass pollen allergic children, and adolescents with asthma, and in primary HDM-induced asthma in adolescents aged from 14 years. In younger children with HDM-allergic asthma, the efficacy of SLIT is not clear definitely. The evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of SCIT and SLIT for the treatment of pediatric asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis concluded that SCIT reduces symptoms and medication scores, whereas SLIT can improve asthma symptoms [54]. New well-controlled studies are required for pediatric age group.

Before AIT initiated, parents should be advised for its benefits, risks, and costs. Information should also include the expected onset of efficacy and duration of treatment, and importance of adhering to the immunotherapy schedule. We recommend that AIT should be individualized for each patient according to degree of sensitization, concomitant allergies, exposures and patient's preference.

Currently, there are no specific tests or clinical markers that can differentiate the patients who may relapse and those who remain in long-term clinical remission after cessation of effective AIT. The duration of treatment should be specified by the physician and patient after considering the risks and benefits associated with discontinuing or continuing immunotherapy [56].

Pediatric asthma is a heterogeneous disease, which can appear with different endotypes [55]. Moreover, in pediatric asthmatics, allergens are often but not always the sole triggers of the inflammatory process. These factors can clarify the variable efficacy of pharmacotherapy, allergen avoidance measures, and AIT itself.

Although there are some contoversies about the efficacy and safety of allergen immunotherapy in children younger than 5 years, there are a few reports concerning effectiveness of AIT in this age group [60]. It has been demonstrated that allergen immunotherapy might prevent asthma in children with allergic rhinitis [61]. However, allergen immunotherapy for inhalant allergens is usually not considered in infants and toddlers because there might be difficulty in communicating with the child in terms of systemic reactions and injections can be traumatic to very young children. Therefore each patient should be evaluated individually by considering the benefits and risks [56].

Some patients with both allergic rhinitis and asthma treated by specialists are polysensitized. Not all of these sensitivities are clinically important. Selection of the relevant allergen is usually based on the combination of history with results of skin prick or in vitro tests [54]. Relevant allergens are major contributors to the safety and efficacy of the allergenic extracts used for AIT.

Most of the published randomized controlled studies of both SCIT and SLIT are with single allergen extracts. There is conflicting results for the efficacy of allergen mixes [6263].

An alternative to allergen mixes for both SLIT and SCIT is the administration of multiple allergen extracts at different times during the day or different locations [62].

Omalizumab, a monoclonal anti-IgE antibody, has been successfully used as a supplementary therapy to improve asthma control in children aged ≥6 years with severe persistent allergic asthma [64].

Omalizumab pretreatment has been shown to improve the safety and tolerability of cluster and rush immunotherapy schedules in patients with moderate persistent asthma and allergic rhinitis, respectively [6465]. Additionally, omalizumab in combination with immunotherapy has been demonstrated to be effective in ameliorating symptom scores compared with immunotherapy alone [65]. In a recently published study, 17 Polish children and adolescents aged 7–18 years with severe uncontrolled asthma who did not tolerate the allergen immunotherapy were treated with omalizumab [66]. All patients had multiple allergies; the most clinically important allergens were HDM (n = 15) and molds (n = 2). The treatment with omalizumab over 6 months was found clinically effective in all patients (i.e., decrease in the number of asthma attacks and hospitalizations, significant reduction in steroid use). This effect of omalizumab permitted the initiation of AIT in children with severe asthma. The studies about administration of AIT with pretreatment or in combination with omalizumab are scarce in children with severe asthma; further studies are needed to evaluate the benefit and risk ratio.

It should be confidently stated that SLIT and SCIT can be used in combination with asthma medications, when asthma is associated with rhinitis and the causal role of the allergen is clearly confirmed. It does not seem that AIT can worsen asthma, whereas uncontrolled asthma remains a significant risk factor for side effects. Official documents recommend that AIT should not be started in patients with unstable asthma; in these cases, SIT can be initiated after well asthma control with appropriate pharmacotherapy. A measurable clinical benefit on asthma symptoms along with steroid-sparing effect is expected. AIT cannot be presently recommended as single therapy when asthma is the single presentation of respiratory allergy.

In children, there are two important points which should be taken into consideration when making a decision on starting AIT. The first is, steroid sparing effect of AIT which gives a significant advantage for children who have to use inhaled corticosteroids in high doses for the control of asthma symptoms over many years. The second point is disease modifying effect of AIT which reduce the risk of asthma onset in children with allergic rhinitis.

Further pediatric studies should evaluate the real-world ef fectiveness of SCIT and SLIT, addressing problems of compliance, which are especially important in children. In addition, direct comparisons of SCIT versus SLIT should assess long-term outcomes such as prevention of asthma and potential for disease modification. Investigating the various effects of immunotherapy based on the developmental stage of children and adolescents can help to identify the optimal dose, frequency, treatment duration, and age for starting to treatment. Better selection of well-responders based on endotype-driven approache is expected to increase both efficacy and safety.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Double-blind placebo-controlled SCIT studies carried out in children with asthma

SCIT, subcutaneous immunotherapy; PFT, pulmonary function; HDM, house dust mite; SD, significantly decreased; NS, not significant; BHR, bronchial hyperreactivity; SPT, skin prick test; SI, significantly increased; VAS, visual analog scale; NA, not available.

*Studies included children with asthma alone (without allergic rhinitis/rhinoconjunctivitis).

References

1. National Center for Health Statistics [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Preventon;cited 2015 Oct 5. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/ashtma03-05/asthma03-05.htm.

2. Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, Drazen JM, FitzGerald M, Gibson P, Ohta K, O'Byrne P, Pedersen SE, Pizzichini E, Sullivan SD, Wenzel SE, Zar HJ. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008; 31:143–178.

3. The Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention (2015 update) [Internet]. The Global Initiative for Asthma;cited 2015 Jul 15. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/documents/5/documents_variants/59.

4. Kulig M, Bergmann R, Tacke U, Wahn U, Guggenmoos-Holzmann I. Long-lasting sensitization to food during the first two years precedes allergic airway disease. The MAS Study Group, Germany. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1998; 9:61–67.

5. Lau S, Illi S, Sommerfeld C, Niggemann B, Bergmann R, von Mutius E, Wahn U. Early exposure to house-dust mite and cat allergens and development of childhood asthma: a cohort study. Multicentre Allergy Study Group. Lancet. 2000; 356:1392–1397.

7. Akdis CA. Therapies for allergic inflammation: refining strategies to induce tolerance. Nat Med. 2012; 18:736–749.

8. Radulovic S, Calderon MA, Wilson D, Durham S. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; (12):CD002893.

9. Compalati E, Passalacqua G, Bonini M, Canonica GW. The efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy for house dust mites respiratory allergy: results of a GA2LEN meta-analysis. Allergy. 2009; 64:1570–1579.

10. Burks AW, Calderon MA, Casale T, Cox L, Demoly P, Jutel M, Nelson H, Akdis CA. Update on allergy immunotherapy: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology/PRACTALL consensus report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013; 131:1288–1296.e3.

11. Pifferi M, Baldini G, Marrazzini G, Baldini M, Ragazzo V, Pietrobelli A, Boner AL. Benefits of immunotherapy with a standardized Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract in asthmatic children: a three-year prospective study. Allergy. 2002; 57:785–790.

12. Roberts G, Hurley C, Turcanu V, Lack G. Grass pollen immunotherapy as an effective therapy for childhood seasonal allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 117:263–268.

13. Ibero M, Castillo MJ. Significant improvement of specific bronchial hyperreactivity in asthmatic children after 4 months of treatment with a modified extract of dermatophagoides pteronyssinus. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2006; 16:194–202.

14. Cantani A, Arcese G, Lucenti P, Gagliesi D, Bartolucci M. A three-year prospective study of specific immunotherapy to inhalant allergens: evidence of safety and efficacy in 300 children with allergic asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1997; 7:90–97.

15. Tabar AI, Lizaso MT, Garcia BE, Gomez B, Echechipia S, Aldunate MT, Madariaga B, Martínez A. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of Alternaria alternata immunotherapy: clinical efficacy and safety. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008; 19:67–75.

16. Kuna P, Kaczmarek J, Kupczyk M. Efficacy and safety of immunotherapy for allergies to Alternaria alternata in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 127:502–508. 508.e1–508.e6.

17. Tsai TC, Lu JH, Chen SJ, Tang RB. Clinical efficacy of house dust mite-specific immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010; 51:14–18.

18. Abramson MJ, Puy RM, Weiner JM. Injection allergen immunotherapy for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; (8):CD001186.

19. Zielen S, Kardos P, Madonini E. Steroid-sparing effects with allergen-specific immunotherapy in children with asthma: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126:942–949.

20. Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Casale T, Lockey RF, Baena-Cagnani CE, Pawankar R, Potter PC, Bousquet PJ, Cox LS, Durham SR, Nelson HS, Passalacqua G, Ryan DP, Brozek JL, Compalati E, Dahl R, Delgado L, van Wijk RG, Gower RG, Ledford DK, Filho NR, Valovirta EJ, Yusuf OM, Zuberbier T, Akhanda W, Almarales RC, Ansotegui I, Bonifazi F, Ceuppens J, Chivato T, Dimova D, Dumitrascu D, Fontana L, Katelaris CH, Kaulsay R, Kuna P, Larenas-Linnemann D, Manoussakis M, Nekam K, Nunes C, O'Hehir R, Olaguibel JM, Onder NB, Park JW, Priftanji A, Puy R, Sarmiento L, Scadding G, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Seberova E, Sepiashvili R, Solé D, Togias A, Tomino C, Toskala E, Van Beever H, Vieths S. Sub-lingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization Position Paper 2009. Allergy. 2009; 64:Suppl 91. 1–59.

21. De Castro G, Zicari AM, Indinnimeo L, Tancredi G, di Coste A, Occasi F, Castagna G, Giancane G, Duse M. Efficacy of sublingual specific immunotherapy on allergic asthma and rhinitis in children's real life. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013; 17:2225–2231.

22. Peng W, Liu E. Factors influencing the response to specific immunotherapy for asthma in children aged 5-16 years. Pediatr Int. 2013; 55:680–684.

23. Penagos M, Compalati E, Tarantini F, Baena-Cagnani R, Huerta J, Passalacqua G, Canonica GW. Efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy in the treatment of allergic rhinitis in pediatric patients 3 to 18 years of age: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006; 97:141–148.

24. Penagos M, Passalacqua G, Compalati E, Baena-Cagnani CE, Orozco S, Pedroza A, Canonica GW. Metaanalysis of the efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy in the treatment of allergic asthma in pediatric patients, 3 to 18 years of age. Chest. 2008; 133:599–609.

25. Olaguíbel JM, Alvarez Puebla MJ. Efficacy of sublingual allergen vaccination for respiratory allergy in children. Conclusions from one meta-analysis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2005; 15:9–16.

26. Calamita Z, Saconato H, Pela AB, Atallah AN. Efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy in asthma: systematic review of randomized-clinical trials using the Cochrane Collaboration method. Allergy. 2006; 61:1162–1172.

27. Canonica GW, Cox L, Pawankar R, Baena-Cagnani CE, Blaiss M, Bonini S, Bousquet J, Calderon M, Compalati E, Durham SR, van Wijk RG, Larenas-Linnemann D, Nelson H, Passalacqua G, Pfaar O, Rosario N, Ryan D, Rosenwasser L, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Senna G, Valovirta E, Van Bever H, Vichyanond P, Wahn U, Yusuf O. Sublingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization position paper 2013 update. World Allergy Organ J. 2014; 7:6.

28. Larenas-Linnemann D, Blaiss M, Van Bever HP, Compalati E, Baena-Cagnani CE. Pediatric sublingual immunotherapy efficacy: evidence analysis, 2009-2012. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013; 110:402–415.e9.

29. Liao W, Hu Q, Shen LL, Hu Y, Tao HF, Li HF, Fan WT. Sublingual immunotherapy for asthmatic children sensitized to house dust mite: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94:e701.

30. Stelmach I, Kaczmarek-Woźniak J, Majak P, Olszowiec-Chlebna M, Jerzynska J. Efficacy and safety of high-doses sublingual immunotherapy in ultra-rush scheme in children allergic to grass pollen. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009; 39:401–408.

31. Keles S, Karakoc-Aydiner E, Ozen A, Izgi AG, Tevetoglu A, Akkoc T, Bahceciler NN, Barlan I. A novel approach in allergen-specific immunotherapy: combination of sublingual and subcutaneous routes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 128:808–815.e7.

32. Eifan AO, Akkoc T, Yildiz A, Keles S, Ozdemir C, Bahceciler NN, Barlan IB. Clinical efficacy and immunological mechanisms of sublingual and subcutaneous immunotherapy in asthmatic/rhinitis children sensitized to house dust mite: an open randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010; 40:922–932.

33. Yukselen A, Kendirli SG, Yilmaz M, Altintas DU, Karakoc GB. Effect of one-year subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy on clinical and laboratory parameters in children with rhinitis and asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, double-dummy study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012; 157:288–298.

34. Mosges R, Graute V, Christ H, Sieber HJ, Wahn U, Niggemann B. Safety of ultra-rush titration of sublingual immunotherapy in asthmatic children with tree-pollen allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010; 21:1135–1138.

35. Pozzan M, Milani M. Efficacy of sublingual specific immunotherapy in patients with respiratory allergy to Alternaria alternata: a randomised, assessor-blinded, patient-reported outcome, controlled 3-year trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010; 26:2801–2806.

37. Normansell R, Kew KM, Bridgman AL. Sublingual immunotherapy for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (8):CD011293.

38. Möller C, Dreborg S, Ferdousi HA, Halken S, Host A, Jacobsen L, Koivikko A, Koller DY, Niggemann B, Norberg LA, Urbanek R, Valovirta E, Wahn U. Pollen immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis (the PAT-study). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 109:251–256.

39. Novembre E, Galli E, Landi F, Caffarelli C, Pifferi M, De Marco E, Burastero SE, Calori G, Benetti L, Bonazza P, Puccinelli P, Parmiani S, Bernardini R, Vierucci A. Coseasonal sublingual immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 114:851–857.

40. Jacobsen L, Niggemann B, Dreborg S, Ferdousi HA, Halken S, Høst A, Koivikko A, Norberg LA, Valovirta E, Wahn U, Möller C. (The PAT investigator group). Specific immunotherapy has long-term preventive effect of seasonal and perennial asthma: 10-year follow-up on the PAT study. Allergy. 2007; 62:943–948.

41. Marogna M, Tomassetti D, Bernasconi A, Colombo F, Massolo A, Businco AD, Canonica GW, Passalacqua G, Tripodi S. Preventive effects of sublingual immunotherapy in childhood: an open randomized controlled study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008; 101:206–211.

42. Des Roches A, Paradis L, Menardo JL, Bouges S, Daurés JP, Bousquet J. Immunotherapy with a standardized Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract. VI. Specific immunotherapy prevents the onset of new sensitizations in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997; 99:450–453.

43. Pajno GB, Barberio G, De Luca F, Morabito L, Parmiani S. Prevention of new sensitizations in asthmatic children monosensitized to house dust mite by specific immunotherapy. A six-year follow-up study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001; 31:1392–1397.

44. Inal A, Altintas DU, Yilmaz M, Karakoc GB, Kendirli SG, Sertdemir Y. Prevention of new sensitizations by specific immunotherapy in children with rhinitis and/or asthma monosensitized to house dust mite. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2007; 17:85–91.

45. Valovirta E, Berstad AK, de Blic J, Bufe A, Eng P, Halken S, Ojeda P, Roberts G, Tommerup L, Varga EM, Winnergard I. GAP investigators. Design and recruitment for the GAP trial, investigating the preventive effect on asthma development of an SQ-standardized grass allergy immunotherapy tablet in children with grass pollen-induced allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Clin Ther. 2011; 33:1537–1546.

46. Bernstein DI, Epstein T, Murphy-Berendts K, Liss GM. Surveillance of systemic reactions to subcutaneous immunotherapy injections: year 1 outcomes of the ACAAI and AAAAI collaborative study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010; 104:530–535.

47. Schiappoli M, Ridolo E, Senna G, Alesina R, Antonicelli L, Asero R, Costantino MT, Longo R, Musarra A, Nettis E, Crivellaro M, Savi E, Massolo A, Passalacqua G. A prospective Italian survey on the safety of subcutaneous immunotherapy for respiratory allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009; 39:1569–1574.

48. Aaronson DW, Gandhi TK. Incorrect allergy injections: allergists' experiences and recommendations for prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 113:1117–1121.

49. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter second update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 120:3 Suppl. S25–S85.

50. Cox LS, Larenas Linnemann D, Nolte H, Weldon D, Finegold I, Nelson HS. Sublingual immunotherapy: a comprehensive review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 117:1021–1035.

51. Calderón MA, Simons FE, Malling HJ, Lockey RF, Moingeon P, Demoly P. Sublingual allergen immunotherapy: mode of action and its relationship with the safety profile. Allergy. 2012; 67:302–311.

52. Passalacqua G, Rogkakou A, Mincarini M, Canonica GW. Allergen immunotherapy in asthma; what is new? Asthma Res Pract. 2015; 1:1–6.

53. Jutel M, Agache I, Bonini S, Burks AW, Calderon M, Canonica W, Cox L, Demoly P, Frew AJ, O'Hehir R, Kleine-Tebbe J, Muraro A, Lack G, Larenas D, Levin M, Nelson H, Pawankar R, Pfaar O, van Ree R, Sampson H, Santos AF, Du Toit G, Werfel T, Gerth van Wijk R, Zhang L, Akdis CA. International consensus on allergy immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015; 136:556–568.

54. Jutel M. Allergen-specific immunotherapy in asthma. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2014; 1:213–219.

55. Cox L, Nelson H, Lockey R, Calabria C, Chacko T, Finegold I, Nelson M, Weber R, Bernstein DI, Blessing-Moore J, Khan DA, Lang DM, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer J, Portnoy JM, Randolph C, Schuller DE, Spector SL, Tilles S, Wallace D. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter third update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 127:1 Suppl. S1–S55.

56. Bernstein DI, Wanner M, Borish L, Liss GM. Immunotherapy Committee, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Twelve-year survey of fatal reactions to allergen injections and skin testing: 1990-2001. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 113:1129–1136.

57. Amin HS, Liss GM, Bernstein DI. Evaluation of near-fatal reactions to allergen immunotherapy injections. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 117:169–175.

58. Reid MJ, Lockey RF, Turkeltaub PC, Platts-Mills TA. Survey of fatalities from skin testing and immunotherapy 1985-1989. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993; 92(1 Pt 1):6–15.

59. Lockey RF, Benedict LM, Turkeltaub PC, Bukantz SC. Fatalities from immunotherapy (IT) and skin testing (ST). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987; 79:660–677.

60. Eng PA, Borer-Reinhold M, Heijnen IA, Gnehm HP. Twelve-year follow-up after discontinuation of preseasonal grass pollen immunotherapy in childhood. Allergy. 2006; 61:198–201.

61. Calderon MA, Cox LS. Monoallergen sublingual immunotherapy versus multiallergen subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic respiratory diseases: a debate during the AAAAI 2013 Annual Meeting in San Antonio, Texas. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014; 2:136–143.

62. Nelson HS. Multiallergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 123:763–769.

63. Brodlie M, McKean MC, Moss S, Spencer DA. The oral corticosteroid-sparing effect of omalizumab in children with severe asthma. Arch Dis Child. 2012; 97:604–609.

64. Kopp MV, Hamelmann E, Bendiks M, Zielen S, Kamin W, Bergmann KC, Klein C, Wahn U. DUAL study group. Transient impact of omalizumab in pollen allergic patients undergoing specific immunotherapy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013; 24:427–433.

65. Kuehr J, Brauburger J, Zielen S, Schauer U, Kamin W, Von Berg A, Leupold W, Bergmann KC, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Gräve M, Hultsch T, Wahn U. Efficacy of combination treatment with anti-IgE plus specific immunotherapy in polysensitized children and adolescents with seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 109:274–280.

66. Stelmach I, Majak P, Jerzynska J, Bojo M, Cichalewski Ł, Smejda K. Children with severe asthma can start allergen immunotherapy after controlling asthma with omalizumab: a case series from Poland. Arch Med Sci. 2015; 11:901–904.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download